A Comparative Study of U Nu and Sihanouk

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Revolution, Reform and Regionalism in Southeast Asia

Revolution, Reform and Regionalism in Southeast Asia Geographically, Cambodia, Laos and Vietnam are situated in the fastest growing region in the world, positioned alongside the dynamic economies of neighboring China and Thailand. Revolution, Reform and Regionalism in Southeast Asia compares the postwar political economies of these three countries in the context of their individual and collective impact on recent efforts at regional integration. Based on research carried out over three decades, Ronald Bruce St John highlights the different paths to reform taken by these countries and the effect this has had on regional plans for economic development. Through its comparative analysis of the reforms implemented by Cam- bodia, Laos and Vietnam over the last 30 years, the book draws attention to parallel themes of continuity and change. St John discusses how these countries have demonstrated related characteristics whilst at the same time making different modifications in order to exploit the strengths of their individual cultures. The book contributes to the contemporary debate over the role of democratic reform in promoting economic devel- opment and provides academics with a unique insight into the political economies of three countries at the heart of Southeast Asia. Ronald Bruce St John earned a Ph.D. in International Relations at the University of Denver before serving as a military intelligence officer in Vietnam. He is now an independent scholar and has published more than 300 books, articles and reviews with a focus on Southeast Asia, -

Aung San Suu Kyi (1945- )

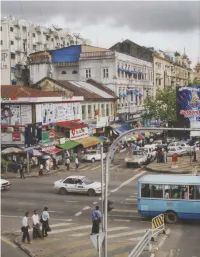

Aung San Suu Kyi (1945 - ) Major Events in the Life of a Revolutionary Leader All terms appearing in bold are included in the glossary. 1945 On June 19 in Rangoon (now called Yangon), the capital city of Burma (now called Myanmar), Aung San Suu Kyi was born the third child and only daughter to Aung San, national hero and leader of the Burma Independence Army (BIA) and the Anti-Fascist People’s Freedom League (AFPFL), and Daw Khin Kyi, a nurse at Rangoon General Hospital. Aung San Suu Kyi was born into a country with a complex history of colonial domination that began late in the nineteenth century. After a series of wars between Burma and Great Britain, Burma was conquered by the British and annexed to British India in 1885. At first, the Burmese were afforded few rights and given no political autonomy under the British, but by 1923 Burmese nationals were permitted to hold select government offices. In 1935, the British separated Burma from India, giving the country its own constitution, an elected assembly of Burmese nationals, and some measure of self-governance. In 1941, expansionist ambitions led the Japanese to invade Burma, where they defeated the British and overthrew their colonial administration. While at first the Japanese were welcomed as liberators, under their rule more oppressive policies were instituted than under the British, precipitating resistance from Burmese nationalist groups like the Anti-Fascist People’s Freedom League (AFPFL). In 1945, Allied forces drove the Japanese out of Burma and Britain resumed control over the country. 1947 Aung San negotiated the full independence of Burma from British control. -

Shwe U Daung and the Burmese Sherlock Holmes: to Be a Modern Burmese Citizen Living in a Nation‐State, 1889 – 1962

Shwe U Daung and the Burmese Sherlock Holmes: To be a modern Burmese citizen living in a nation‐state, 1889 – 1962 Yuri Takahashi Southeast Asian Studies School of Languages and Cultures Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences The University of Sydney April 2017 A thesis submitted in fulfilment of requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Statement of originality This is to certify that to the best of my knowledge, the content of this thesis is my own work. This thesis has not been submitted for any degree or other purposes. I certify that the intellectual content of this thesis is the product of my own work and that all the assistance received in preparing this thesis and sources has been acknowledged. Yuri Takahashi 2 April 2017 CONTENTS page Acknowledgements i Notes vi Abstract vii Figures ix Introduction 1 Chapter 1 Biography Writing as History and Shwe U Daung 20 Chapter 2 A Family after the Fall of Mandalay: Shwe U Daung’s Childhood and School Life 44 Chapter 3 Education, Occupation and Marriage 67 Chapter ‘San Shar the Detective’ and Burmese Society between 1917 and 1930 88 Chapter 5 ‘San Shar the Detective’ and Burmese Society between 1930 and 1945 114 Chapter 6 ‘San Shar the Detective’ and Burmese Society between 1945 and 1962 140 Conclusion 166 Appendix 1 A biography of Shwe U Daung 172 Appendix 2 Translation of Pyone Cho’s Buddhist songs 175 Bibliography 193 i ACKNOWLEGEMENTS I came across Shwe U Daung’s name quite a long time ago in a class on the history of Burmese literature at Tokyo University of Foreign Studies. -

National Catholic Reporter

Seing Red: Amencan Foreign Policy Towards Vietnam and the Khmer Rouge, 1975 to 1982 Brenda Fewster A Thesis in The Department of History Presented in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Ans at Concordia University Montreal, Quebec, Canada April2000 0 Brenda Fewster, 2000 National Library Bibliothèque nationale 1+1 ,,na& du Canada Acquisitions and Acquisitions et Bibliographic Services services bibliographiques 395 Wellington StmBt 395. rue Wdlingtori OnawaON KlAON4 OitawaON K1AW Canada CaMda The author has granted a non- L'auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive licence allowing the exclusive permettant à la National Library of Canada to Bibliothèque nationale du Canada de reproduce, loan, distribute or seil reproduire, prêter, distribuer ou copies of this thesis in microforni, vendre des copies de cette thèse sous paper or electronic formats. la forme de microfiche/nlm, de reproduction sur papier ou sur format électronique. The author retains ownership of the L'auteur conserve la propriété du copyright in this thesis. Neither the droit d'auteur qui protège cette thèse. thesis nor substantial extracts fiom it Ni la thèse ni des extraits substantiels may be printed or otherwise de celle-ci ne doivent être imprimés reproduced without the author's ou autrement reproduits sans son permission. autorisation. ABSTRACT Seeing Red: Arnerican Foreign Policy Towards Vietnam and the Khmer Rouge, 1975- 1982 Brenda Fewster Between 1979 and 1982 the US supported the Khmer Rouge in the refiigee camps along the Thai-Cambodian border, in the Security Council of the United Nations, and in behind-closed-doors discussions seeking to ensure a place for the Khmer Rouge (as an med force) in a coalition government. -

Burma Road to Poverty: a Socio-Political Analysis

THE BURMA ROAD TO POVERTY: A SOCIO-POLITICAL ANALYSIS' MYA MAUNG The recent political upheavals and emergence of what I term the "killing field" in the Socialist Republic of Burma under the military dictatorship of Ne Win and his successors received feverish international attention for the brief period of July through September 1988. Most accounts of these events tended to be journalistic and failed to explain their fundamental roots. This article analyzes and explains these phenomena in terms of two basic perspec- tives: a historical analysis of how the states of political and economic devel- opment are closely interrelated, and a socio-political analysis of the impact of the Burmese Way to Socialism 2, adopted and enforced by the military regime, on the structure and functions of Burmese society. Two main hypotheses of this study are: (1) a simple transfer of ownership of resources from the private to the public sector in the name of equity and justice for all by the military autarchy does not and cannot create efficiency or elevate technology to achieve the utopian dream of economic autarky and (2) the Burmese Way to Socialism, as a policy of social change, has not produced significant and fundamental changes in the social structure, culture, and personality of traditional Burmese society to bring about modernization. In fact, the first hypothesis can be confirmed in light of the vicious circle of direct controls-evasions-controls whereby military mismanagement transformed Burma from "the Rice Bowl of Asia," into the present "Rice Hole of Asia." 3 The second hypothesis is more complex and difficult to verify, yet enough evidence suggests that the tradi- tional authoritarian personalities of the military elite and their actions have reinforced traditional barriers to economic growth. -

The Languages of Pyidawtha and the Burmese Approach to National Development1

The languages of Pyidawtha and the Burmese approach to national development1 Tharaphi Than Abstract: Burma’s first well known welfare plan was entitled Pyidawtha or Happy Land, and it was launched in 1952. In vernacular terms, the literal mean- ing of Pyidawtha is ‘Prosperous Royal Country’. The government’s attempt to sustain tradition and culture and to instil modern aspirations in its citizens was reflected in its choice of the word Pyidawtha. The Plan failed and its impli- cations still overshadow the development framework of Burma. This paper discusses how the country’s major decisions, including whether or not to join the Commonwealth, have been influenced by language; how the term and con- cept of ‘development’ were conceived; how the Burmese translation was coined to attract public support; and how the detailed planning was presented to the masses by the government. The paper also discusses the concerns and anxie- ties of the democratic government led by U Nu in introducing Burma’s first major development plan to a war-torn and bitterly divided country, and why it eventually failed. Keywords: welfare plan; poverty alleviation; insurgency; communism; Pyidawtha; Burmese language Author details: Tharaphi Than is an Assistant Professor in the Department of For- eign Languages and Literatures at Northern Illinois University, DeKalb, IL 60115, USA. E-mail: [email protected]. In May 2011, the new government of Burma convened a workshop entitled ‘Rural Development and Poverty Alleviation’.2 Convened almost 50 years after Burma’s first Development Conference, called Pyidawtha, the 2011 workshop shared some of the ideologies of the Pyidawtha Plan under the government led by Nu. -

American Visions of the Netherlands East Indies/ Indonesia: US Foreign Policy and Indonesian Nationalism, 1920-1949 Gouda, Frances; Brocades Zaalberg, Thijs

www.ssoar.info American Visions of the Netherlands East Indies/ Indonesia: US Foreign Policy and Indonesian Nationalism, 1920-1949 Gouda, Frances; Brocades Zaalberg, Thijs Veröffentlichungsversion / Published Version Monographie / monograph Zur Verfügung gestellt in Kooperation mit / provided in cooperation with: OAPEN (Open Access Publishing in European Networks) Empfohlene Zitierung / Suggested Citation: Gouda, F., & Brocades Zaalberg, T. (2002). American Visions of the Netherlands East Indies/Indonesia: US Foreign Policy and Indonesian Nationalism, 1920-1949. (American Studies). Amsterdam: Amsterdam Univ. Press. https://nbn- resolving.org/urn:nbn:de:0168-ssoar-337325 Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Dieser Text wird unter einer CC BY-NC-ND Lizenz This document is made available under a CC BY-NC-ND Licence (Namensnennung-Nicht-kommerziell-Keine Bearbeitung) zur (Attribution-Non Comercial-NoDerivatives). For more Information Verfügung gestellt. Nähere Auskünfte zu den CC-Lizenzen finden see: Sie hier: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/deed.de FRANCES GOUDA with THIJS BROCADES ZAALBERG AMERICAN VISIONS of the NETHERLANDS EAST INDIES/INDONESIA US Foreign Policy and Indonesian Nationalism, 1920-1949 AMSTERDAM UNIVERSITY PRESS de 3e PROEF - BOEK 29-11-2001 23:41 Pagina 1 AMERICAN VISIONS OF THE NETHERLANDS EAST INDIES/INDONESIA de 3e PROEF - BOEK 29-11-2001 23:41 Pagina 2 de 3e PROEF - BOEK 29-11-2001 23:41 Pagina 3 AmericanVisions of the Netherlands East Indies/Indonesia -

Myanmar-Jews.Pdf

8*9** Letter Myanmar-- from After decades of repressive military rule, Burma’s Jewish community has dwindled to about 20 members. Is there hope for its future? A rare look at life inside the isolated country. Story by Jeremy Gillick Photos by Chris Daw As the sun sets in Burma, now known as Myanmar, a small group of Jews descends on the Park Royal Hotel in down town Yangon, formerly Rangoon. I arrive unfashionably early, hoping to steal some private time with Sammy Samuels, the debonair Burmese-American host of the third annual Myan mar Jewish Community Dinner Reception. But apparently it is fashionable for Burmese Jews to arrive late, and Sammy is no where to be found. At 6:30, tuxedoed caterers begin distribut ing glasses of Israeli and French wines to guests socializing in the lobby. I chat briefly with Cho, the daughter of Myanmar’s foreign minister, who professes her love for Israel, and then with an impeccably dressed British diplomat who is superb at making small talk. When I ask if I should be concerned about reporting from such a public location, he points to secret po lice lurking in the corners and suggests steering clear of dis cussing politics. “Once you’ve lived here a while, they’re easy to spot,” he says. At last, Sammy himself strides in. Short with a wide face, kind eyes and dark hair puffed up in the front, his relaxed de meanor belies the gravity of the task ahead of him. He is one of perhaps 20 Jews—many of them elderly or intermarried—left in the entire country. -

Weerdesteijn Rationality 12-12-2016

THE RATIONALITY OF DICTATORS A commercial edition of this dissertation will be published by Intersentia under ISBN 978-1-78068-443-7. THE RATIONALITY OF DICTATORS Towards a more effective implementation of the responsibility to protect Proefschrift ter verkrijging van de graad van doctor aan Tilburg University op gezag van de rector magnifi cus, prof. dr. E.H.L. Aarts, in het openbaar te verdedigen ten overstaan van een door het college voor promoties aangewezen commissie in de aula van de Universiteit op maandag 12 december 2016 om 14.00 uur door Maartje Weerdesteijn geboren op 16 september 1984 te Veldhoven Promotiecommissie Promotores: Prof. dr. A.L. Smeulers Prof. mr. T. Kooijmans Overige leden van de promotiecommissie: Prof. dr. A.J. Bellamy Prof. mr. M.S. Groenhuijsen Prof. dr. S. Parmentier Prof. dr. N.M. Rajkovic Prof. dr. W.G. Werner ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Having the opportunity to write this book has been a privilege and I would like to express my appreciation to Tilburg Law School for making this research possible. Furthermore, I would like to thank my supervisors. Th ere have been many people who have infl uenced and inspired me academically, but none more so than Alette Smeulers. I feel fortunate to have had such a phenomenal researcher, gift ed lecturer and above all kind and compassionate person as my supervisor. You always believed in me, you allowed me to believe in myself and I cannot tell you how much this meant to me. Th ank you for only strengthening my love and enthusiasm for the fi eld, for your invaluable comments on my research and for all the advice you have given me throughout the years. -

Historical Patterns of the Racialisation of Vietnamese in Cambodia, and Their Relevance Today, Anna Lewis, 2015

CERS Working Paper 2015 Historical patterns of the racialisation of Vietnamese in Cambodia, and their relevance today Anna Lewis Abbreviations: NICFEC Neutral & Impartial Committee for Free & Fair Elections in Cambodia RFAKS Radio Free Asia Khmer Service UN United Nations UNHRC United Nations Human Rights Council UNICERD United Nations International Convention on the Elimination of all Forms of Racial Discrimination Introduction Relations between Cambodians and Vietnamese have been bitter through most of the region's history. Present day is no different with ethnic Vietnamese falling victim to racial prejudice in Cambodia. RFAKS (2014) estimated that approximately 750,000 of Cambodia's 15 million population are of Vietnamese ethnicity, yet they are constantly referred to as being stateless and in limbo. This paper is going to explore the processes of racialisation that are at play here. Racialisation has been defined as "the process by which [race] becomes meaningful in a particular context" (Garner 2010: 19), involving how racial identities are developed and ascribed to people. To know how ethnic Vietnamese are racialised by Cambodians, especially those who identify as Khmer, four key themes will be studied. Firstly, in order to gain any level of understanding it is essential to understand the historical context. Since the 1600's, the presence of Khmer nationalism has been an undeniable influence on xenophobia, especially when combined with the recurrent loss of Khmer territory to the Vietnamese. The periods discussed will cover the Vietnamese expansion of the 17th Century, the French Protectorate, independence under Sihanouk, Pol Pot's regime, Vietnamese occupation in the 1980's and modern day. -

The Khmer Rouge Practice of Thought Reform in Cambodia, 1975–1978

Journal of Political Ideologies ISSN: 1356-9317 (Print) 1469-9613 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/cjpi20 Converts, not ideologues? The Khmer Rouge practice of thought reform in Cambodia, 1975–1978 Kosal Path & Angeliki Kanavou To cite this article: Kosal Path & Angeliki Kanavou (2015) Converts, not ideologues? The Khmer Rouge practice of thought reform in Cambodia, 1975–1978, Journal of Political Ideologies, 20:3, 304-332, DOI: 10.1080/13569317.2015.1075266 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13569317.2015.1075266 Published online: 25 Nov 2015. Submit your article to this journal View related articles View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=cjpi20 Download by: [24.229.103.45] Date: 26 November 2015, At: 10:12 Journal of Political Ideologies, 2015 Vol. 20, No. 3, 304–332, http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13569317.2015.1075266 Converts, not ideologues? The Khmer Rouge practice of thought reform in Cambodia, 1975–1978 KOSAL PATH Brooklyn College, City University of New York, Brooklyn, NY 11210, USA ANGELIKI KANAVOU Interdisciplinary Center for the Scientific Study of Ethics & Morality, University of California, Irvine, CA 92697-5100, USA ABSTRACT While mistaken as zealot ideologues of Marxist ideals fused with Khmer rhetoric, the Khmer Rouge (KR) cadres’ collective profile better fits that of the convert subjected to intense thought reform. This research combines insights from the process and the context of thought reform informed by local cultural norms with the social type of the convert in a way that captures the KR phenome- non in both its general and particular dimensions. -

Legitimation of Political Violence: the Cases of Hamas and the Khmer Rouge

LEGITIMATION OF POLITICAL VIOLENCE: THE CASES OF HAMAS AND THE KHMER ROUGE Raisa Asikainen & Minna Saarnivaara INTRODUCTION This article discusses the legitimization of political violence in/by two different organizations, namely the Palestinian Hamas and the Khmer Rouge in Cambodia' Both Hamas and the Khmer Rouge fit the category of radical political orgaruza- tions which use violence. In order to analyze the legitimation of political violence, the authors will ponder on the question of what has changed in the use of political violence during the time discussed in this article and, most importantly, how this change has been possible. In this article, Hamas is discussed until spring 2004, when Hamas leader Ahmad Yasin was killed, and the Khmer Rouge is discussed until spring 1975, when it gained power in Cambodia. The reason for this time frame is the radicali- zation of the two organizations. With Hamas, radicalization refers to the increase in the amount of so called suicide attacks against civilians during the period in question. With the Khmer Rouge, radicalization refers to the increasing use of violence towards civilians towards the end of the period in question and the inclu- sion of violence in standard practices such as interrogations. The intemational situation played a key role in both organizations' action. However, due to the scope of this article, this aspect is not scrutinizedin great detail in this article. Violence can be defined as action causing injury to people. The violence discussed in this article is coordinated violence carried out by specific organiza- tions. By political violence the authors refer to violence, the purpose of which is to affect a change in people's actions.