Peace As Complex Legitimacy: Politics, Space and Discourse in Tajikistan’S Peacebuilding Process, 2000-2005

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The University of Chicago Old Elites Under Communism: Soviet Rule in Leninobod a Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the Di

THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO OLD ELITES UNDER COMMUNISM: SOVIET RULE IN LENINOBOD A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE DIVISION OF THE SOCIAL SCIENCES IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY BY FLORA J. ROBERTS CHICAGO, ILLINOIS JUNE 2016 TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Figures .................................................................................................................... iii List of Tables ...................................................................................................................... v Acknowledgements ............................................................................................................ vi A Note on Transliteration .................................................................................................. ix Introduction ......................................................................................................................... 1 Chapter One. Noble Allies of the Revolution: Classroom to Battleground (1916-1922) . 43 Chapter Two. Class Warfare: the Old Boi Network Challenged (1925-1930) ............... 105 Chapter Three. The Culture of Cotton Farms (1930s-1960s) ......................................... 170 Chapter Four. Purging the Elite: Politics and Lineage (1933-38) .................................. 224 Chapter Five. City on Paper: Writing Tajik in Stalinobod (1930-38) ............................ 282 Chapter Six. Islam and the Asilzodagon: Wartime and Postwar Leninobod .................. 352 Chapter Seven. The -

The Republic of Tajikistan Ministry of Energy and Industry

The Republic of Tajikistan Ministry of Energy and Industry DATA COLLECTION SURVEY ON THE INSTALLMENT OF SMALL HYDROPOWER STATIONS FOR THE COMMUNITIES OF KHATLON OBLAST IN THE REPUBLIC OF TAJIKISTAN FINAL REPORT September 2012 Japan International Cooperation Agency NEWJEC Inc. E C C CR (1) 12-005 Final Report Contents, List of Figures, Abbreviations Data Collection Survey on the Installment of Small Hydropower Stations for the Communities of Khatlon Oblast in the Republic of Tajikistan FINAL REPORT Table of Contents Summary Chapter 1 Preface 1.1 Objectives and Scope of the Study .................................................................................. 1 - 1 1.2 Arrangement of Small Hydropower Potential Sites ......................................................... 1 - 2 1.3 Flowchart of the Study Implementation ........................................................................... 1 - 7 Chapter 2 Overview of Energy Situation in Tajikistan 2.1 Economic Activities and Electricity ................................................................................ 2 - 1 2.1.1 Social and Economic situation in Tajikistan ....................................................... 2 - 1 2.1.2 Energy and Electricity ......................................................................................... 2 - 2 2.1.3 Current Situation and Planning for Power Development .................................... 2 - 9 2.2 Natural Condition ............................................................................................................ -

TAJIKISTAN TAJIKISTAN Country – Livestock

APPENDIX 15 TAJIKISTAN 870 км TAJIKISTAN 414 км Sangimurod Murvatulloev 1161 км Dushanbe,Tajikistan / [email protected] Tel: (992 93) 570 07 11 Regional meeting on Foot-and-Mouth Disease to develop a long term regional control strategy (Regional Roadmap for West Eurasia) 1206 км Shiraz, Islamic Republic of Iran 3 651 . 9 - 13 November 2008 Общая протяженность границы км Regional meeting on Foot-and-Mouth Disease to develop a long term Regional control strategy (Regional Roadmap for West Eurasia) TAJIKISTAN Country – Livestock - 2007 Territory - 143.000 square km Cities Dushanbe – 600.000 Small Population – 7 mln. Khujand – 370.000 Capital – Dushanbe Province Cattle Dairy Cattle ruminants Yak Kurgantube – 260.000 Official language - tajiki Kulob – 150.000 Total in Ethnic groups Tajik – 75% Tajikistan 1422614 756615 3172611 15131 Uzbek – 20% Russian – 3% Others – 2% GBAO 93619 33069 267112 14261 Sughd 388486 210970 980853 586 Khatlon 573472 314592 1247475 0 DRD 367037 197984 677171 0 Regional meeting on Foot-and-Mouth Disease to develop a long term Regional control strategy Regional meeting on Foot-and-Mouth Disease to develop a long term Regional control strategy (Regional Roadmap for West Eurasia) (Regional Roadmap for West Eurasia) Country – Livestock - 2007 Current FMD Situation and Trends Density of sheep and goats Prevalence of FM D population in Tajikistan Quantity of beans Mastchoh Asht 12827 - 21928 12 - 30 Ghafurov 21929 - 35698 31 - 46 Spitamen Zafarobod Konibodom 35699 - 54647 Spitamen Isfara M astchoh A sht 47 -

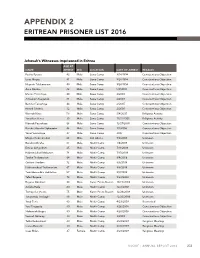

Prisoner Lists USCIRF 2016 Annual Report.Pdf

APPENDIX 2 ERITREAN PRISONER LIST 2016 Jehovah’s Witnesses Imprisoned in Eritrea AGE AT NAME ARREST SEX LOCATION DATE OF ARREST REASON Paulos Eyassu 43 Male Sawa Camp 9/24/1994 Conscientious Objection Isaac Mogos 41 Male Sawa Camp 9/24/1994 Conscientious Objection Negede Teklemariam 40 Male Sawa Camp 9/24/1994 Conscientious Objection Aron Abraha 42 Male Sawa Camp 5/9/2001 Conscientious Objection Mussie Fessehaya 44 Male Sawa Camp 6/2003 Conscientious Objection Ambakom Tsegezab 41 Male Sawa Camp 2/2004 Conscientious Objection Bemnet Fessehaye 44 Male Sawa Camp 2/2005 Conscientious Objection Henok Ghebru 32 Male Sawa Camp 2/2005 Conscientious Objection Worede Kiros 59 Male Sawa Camp 5/4/2005 Religious Activity Yonathan Yonas 30 Male Sawa Camp 11/12/2005 Religious Activity Kibreab Fessehaye 38 Male Sawa Camp 12/27/2005 Conscientious Objection Bereket Abraha Oqbagabir 46 Male Sawa Camp 1/1/2006 Conscientious Objection Yosief Fessehaye 27 Male Sawa Camp 2007 Conscientious Objection Mogos Gebremeskel 68 Male Adi-Abieto 7/3/2008 Unknown Bereket Abraha 67 Male Meitir Camp 7/8/2008 Unknown Ermias Ashgedom 25 Male Meitir Camp 7/11/2008 Unknown Habtemichael Mekonen 74 Male Meitir Camp 7/17/2008 Unknown Tareke Tesfamariam 64 Male Meitir Camp 8/4/2008 Unknown Goitom Aradom 72 Male Meitir Camp 8/8/2008 Unknown Habtemichael Tesfamariam 67 Male Meitir Camp 8/8/2008 Unknown Tewoldemedhin Habtezion 57 Male Meitir Camp 8/9/2008 Unknown Teferi Beyene 73 Male Meitir Camp 9/23/2008 Unknown Beyene Abraham 63 Male Karen Police Station 10/23/2008 Unknown Asfaha -

ASEAN Workshop on Election Observation

Report from the 2015 ASEAN Workshop on Election Observation Election on ASEAN Workshop 2015 the from Report ASEAN Workshop on Election Observation Incremental Steps Towards the Establishment of an ASEAN Election Observation Mechanism Manila, 24–25 June 2015 Funded by International IDEA ASEAN-ROK Special Cooperation Fund SE -103 34 Stockholm Sweden Phone + 46 8 698 37 00 Fax + 46 8 20 24 22 E-mail: [email protected] Website: http://www.idea.int ASEAN Workshop on Election Observation Incremental Steps Towards the Establishment of an ASEAN Election Observation Mechanism Manila, 24–25 June 2015 Funded by ASEAN-ROK Special Cooperation Fund Writer Sanjay Gathia Content Editors Andrew Ellis Adhy Aman International IDEA resource on the ASEAN election observation mechanism Copyright © 2015 International IDEA Strömsborg, SE - 103 34, Stockholm, Sweden Tel: +46 8 698 37 00 Fax: +46 8 20 24 22 Email: [email protected] Website: www.idea.int International IDEA publications are independent of specific national or political interests. Views expressed in this publication do not necessarily represent the views of International IDEA, its Board or its Council members. Cover photograph courtesy of the Department of Foreign Affairs of the Philippines Foreword The commitment of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) to the principle of ‘adherence to the rule of law, good governance, democracy and constitutional government‘, is becoming increasingly relevant in the evolving and complex political landscape of the region, where democracy is being constantly challenged. The region’s democratic journey has been rather uneven and full of obstacles, although not for lack of commitment and determination. -

Challenges to Education in Tajikistan: the Need for Research-Based Solutions Sarfaroz Niyozov Aga Khan University, [email protected]

eCommons@AKU Book Chapters January 2006 Challenges to education in Tajikistan: The need for research-based solutions Sarfaroz Niyozov Aga Khan University, [email protected] Stephen Bahry University of Toronto, Canada Follow this and additional works at: http://ecommons.aku.edu/book_chapters Part of the Curriculum and Instruction Commons, Curriculum and Social Inquiry Commons, Educational Assessment, Evaluation, and Research Commons, International and Comparative Education Commons, Other Educational Administration and Supervision Commons, and the Other Teacher Education and Professional Development Commons Recommended Citation Niyozov, S., & Stephen, B. (2006). Challenges to education in Tajikistan: The need for research-based solutions. In J. Earnest & D. F. Treagust (Eds.), Education reform in societies in transition: International perspectives (pp. 211–231). Rotterdam: Sense Publishers. SARFAROZ NIYOZOV & STEPHEN BAHRY CHAPTER 14 CHALLENGES TO EDUCATION IN TAJIKISTAN: THE NEED FOR RESEARCH-BASED SOLUTIONS ABSTRACT Education in Tajikistan today is acknowledged by the Ministry of Education ofthe Republic of Tajikistan and by international agencies as facing manychallenges. Infrastructure and materials need replacement or repair; curriculum needs to be adapted to changing conditions; professionaldevelopment for teachers is required, while means to retain experiencedteachers and attract new ones need to be found. At the same time, childrens'meaningful access to education has been threatened by various factors thatreduce their attendance -

Political Parties in Tajikistan (Facts, Figures and Analysis): Final Draft Document Date: 2002

Date Printed: 11/06/2008 JTS Box Number: lFES 12 Tab Number: 6 Document Title: Political Parties in Tajikistan (Facts, Figures and Analysis): Final Draft Document Date: 2002 Document Country: Tajikistan 1FES 10: R0188? I~ * . ..~; 1 ' ·• .......................••••••••••••••••• -II · .. • ••• ~ • ..-~~~~! - ~ •.••;;;;; __ I •••• - -- -----=-= ___ • BS·· •••• ~ : :: .. ::::: -• - ••-- ·"'!I'I~···; .~ . ----• ••• . ., ••••••••••••••••• • ••••••••••••••••• • = ••••••••••••••••• !.a ••••••••••••••••• ~ :~:::::::::::::::::~ .~ ••••••••••••••••• ~ • •••••••••••••••••• :-::::::::::=~=~~::~ :o:::::::::~mLlg~::: • ••••••••• ~ t •••••• - ••••••••• ••• •• ------ --- -~~~ --- _. ••••••••••••••••••••• • •.• • • • • • ~~Wllifu. I IFES MISSION STATEMENT The purpose of IFES is to provide technical assistance in the promotion of democracy worldwide and to serve as a clearinghouse for information about democratic development and elections. IFES is dedicated to the success of democracy throughout the world, believing that it is the preferred form of gov ernment. At the same time, IFES firmly believes that each nation requesting > assistance must take into consideration its unique social, cultural, and envi- ronmental influences. The Foundation recognizes that democracy is a dynam ic process with no single blueprint. IFES is nonpartisan, multinational, and inter disciplinary in its approach. POLITICAL PARTIES IN TAJIKISTAN Facts, Figures, and Analysis FINAL DRAFT Dr. Saodat Olimova Anthony Bowyer November 2002 Prepared by the International Foundation for -

Himalayan and Central Asian Studies

ISSN 0971-9318 HIMALAYAN AND CENTRAL ASIAN STUDIES (JOURNAL OF HIMALAYAN RESEARCH AND CULTURAL FOUNDATION) NGO in Special Consultative Status with ECOSOC, United Nations Vol. 17 No. 3-4 July-December 2013 Political change in China and the new 5th Generation Leadership Michael Dillon Financial Diplomacy: The Internationalization of the Chinese Yuan Ivanka Petkova Understanding China’s Policy and Intentions towards the SCO Michael Fredholm Cyber Warfare: China’s Role and Challenge to the United States Arun Warikoo India and China: Contemporary Issues and Challenges B.R. Deepak The Depsang Standoff at the India-China Border along the LAC: View from Ladakh Deldan Kunzes Angmo Nyachu China- Myanmar: No More Pauk Phaws? Rahul Mishra Pakistan-China Relations: A Case Study of All-Weather Friendship Ashish Shukla Afghanistan-China Relations: 1955-2012 Mohammad Mansoor Ehsan HIMALAYAN AND CENTRAL ASIAN STUDIES Guest Editor : MONDIRA DUTTA © Himalayan Research and Cultural Foundation, New Delhi. * All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted by any means, electrical, mechanical or otherwise without first seeking the written permission of the publisher or due acknowledgement. * The views expressed in this Journal are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the opinions or policies of the Himalayan Research and Cultural Foundation. SUBSCRIPTION IN INDIA Single Copy (Individual) : Rs. 500.00 Annual (Individual) : Rs. 1000.00 Institutions : Rs. 1400.00 & Libraries (Annual) -

45354-002: Building Climate Resilience in the Pyanj River Basin

ENVIRONMENTAL MONITORING REPORT _________________________________________________________________________ April 2021 Annual report Project No. 45354-002 Grant: G0352 Reporting period: 1 January 2020- 31 December 2020 TAJIKISTAN: "BUILDING CLIMATE RESILIENCE IN THE PYANJ RIVER BASIN" Component 1 and 2 (irrigation and flood management) (Financing by the Asian Development Bank) Prepared by the Agency for Land Reclamation and Irrigation under the Government of the Republic of Tajikistan (Project Implementation Unit) for the Asian Development Bank. This environmental monitoring report is a document of the borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily reflect the views of ADB's Board of Directors, its managers, or employees, and may in fact only be preliminary. When preparing any country program or strategy, financing any project, or by any indication or reference to a specific territory or geographic area in this document, the Asian Development Bank does not intend to make any judgments regarding the legal or any other status of any of territories or districts ABBREVIATIONS ADB Asian Development Bank. ALRI Agency for Land Reclamation and Irrigation. CEP Committee on Environment Protection TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................................ 1 1.1 Purpose of the report ................................................................................................................. 2 2 ENVIRONMENTAL MONITORING ................................................................................................ -

The Creation of National Ideologies in Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan Erica Marat

Imagined Past, Uncertain Future The Creation of National Ideologies in Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan Erica Marat National ideologies were a HEN the Central Asian nations inherited statehood as Wa result of the collapse of the Soviet Union in late crucial element in the process 1991, their political elites quickly realized that the new states needed to cultivate a unifying ideology if they were of state-building in the to function as cohesive entities. What with the region’s independent Central Asian fuzzy borders and the dominance of the Russian language and Soviet culture, Central Asian leaders had to develop a states. national idea that would solidify the people’s recognition of post-Soviet statehood and the new political leadership. The urgent need for post-communist ideological programs that would reflect upon the complex Soviet past, accom- modate the identities of majority and minority ethnic groups, and rationalize the collapse of the Soviet Union emerged before the national academic communities could meaningfully discuss the possible content and nature of such ideologies. Attributes for ideological projects were often sought in the pre-Soviet period, when there were no hard national borders and strict cultural boundaries. It was in this idiosyncratic setting that the Central Asian regimes tried to construct national ideological conceptions that would be accessible to the mass public, increase the legitimacy of the ruling political elites, and have an actual historical basis. National ideologies were a crucial element of the state-building processes in the independent Central Asian states. They reflected two major goals of the ruling elites. ERICA MARAT is a research fellow at the Institute for Security & Develop- First, the elites were able to strengthen themselves against ment Policy in Stockholm, Sweden, and the Central Asia–Caucasus Institute competing political forces by mobilizing the entire public at the School of Advanced International Studies, Johns Hopkins University, in Washington, DC. -

CORI Country Report Uzbekistan, November 2010

CORI country of origin research and information CORI Country Report Uzbekistan, November 2010 Commissioned by the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). Any views expressed in this paper are those of the author and are not necessarily those of UNHCR. Preface Country of Origin Information (COI) is required within Refugee Status Determination (RSD) to provide objective evidence on conditions in refugee producing countries to support decision making. Quality information about human rights, legal provisions, politics, culture, society, religion and healthcare in countries of origin is essential in establishing whether or not a person’s fear of persecution is well founded. CORI Country Reports are designed to aid decision making within RSD. They are not intended to be general reports on human rights conditions. They serve a specific purpose, collating legally relevant information on conditions in countries of origin, pertinent to the assessment of claims for asylum. Categories of COI included within this report are based on the most common issues arising from asylum applications made by Uzbekistan nationals. This report covers events up to 30 November 2010. COI is a specific discipline distinct from academic, journalistic or policy writing, with its own conventions and protocols of professional standards as outlined in international guidance such as The Common EU Guidelines on Processing Country of Origin Information, 2008 and UNHCR, Country of Origin Information: Towards Enhanced International Cooperation, 2004. CORI provides information impartially and objectively, the inclusion of source material in this report does not equate to CORI agreeing with its content or reflect CORI’s position on conditions in a country. -

World Bank Document

Ministry of Agriculture and Uzbekistan Agroindustry and Food Security Agency (UZAIFSA) Public Disclosure Authorized Uzbekistan Agriculture Modernization Project Public Disclosure Authorized ENVIRONMENTAL AND SOCIAL MANAGEMENT FRAMEWORK Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Tashkent, Uzbekistan December, 2019 ABBREVIATIONS AND GLOSSARY ARAP Abbreviated Resettlement Action Plan CC Civil Code DCM Decree of the Cabinet of Ministries DDR Diligence Report DMS Detailed Measurement Survey DSEI Draft Statement of the Environmental Impact EHS Environment, Health and Safety General Guidelines EIA Environmental Impact Assessment ES Environmental Specialist ESA Environmental and Social Assessment ESIA Environmental and Social Impact Assessment ESMF Environmental and Social Management Framework ESMP Environmental and Social Management Plan FS Feasibility Study GoU Government of Uzbekistan GRM Grievance Redress Mechanism H&S Health and Safety HH Household ICWC Integrated Commission for Water Coordination IFIs International Financial Institutions IP Indigenous People IR Involuntary Resettlement LAR Land Acquisition and Resettlement LC Land Code MCA Makhalla Citizen’s Assembly MoEI Ministry of Economy and Industry MoH Ministry of Health NGO Non-governmental organization OHS Occupational and Health and Safety ОP Operational Policy PAP Project Affected Persons PCB Polychlorinated Biphenyl PCR Physical Cultural Resources PIU Project Implementation Unit POM Project Operational Manual PPE Personal Protective Equipment QE Qishloq Engineer