Human Rights in Uzbekistan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The University of Chicago Old Elites Under Communism: Soviet Rule in Leninobod a Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the Di

THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO OLD ELITES UNDER COMMUNISM: SOVIET RULE IN LENINOBOD A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE DIVISION OF THE SOCIAL SCIENCES IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY BY FLORA J. ROBERTS CHICAGO, ILLINOIS JUNE 2016 TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Figures .................................................................................................................... iii List of Tables ...................................................................................................................... v Acknowledgements ............................................................................................................ vi A Note on Transliteration .................................................................................................. ix Introduction ......................................................................................................................... 1 Chapter One. Noble Allies of the Revolution: Classroom to Battleground (1916-1922) . 43 Chapter Two. Class Warfare: the Old Boi Network Challenged (1925-1930) ............... 105 Chapter Three. The Culture of Cotton Farms (1930s-1960s) ......................................... 170 Chapter Four. Purging the Elite: Politics and Lineage (1933-38) .................................. 224 Chapter Five. City on Paper: Writing Tajik in Stalinobod (1930-38) ............................ 282 Chapter Six. Islam and the Asilzodagon: Wartime and Postwar Leninobod .................. 352 Chapter Seven. The -

Prisoner Lists USCIRF 2016 Annual Report.Pdf

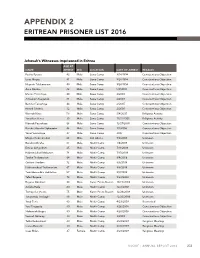

APPENDIX 2 ERITREAN PRISONER LIST 2016 Jehovah’s Witnesses Imprisoned in Eritrea AGE AT NAME ARREST SEX LOCATION DATE OF ARREST REASON Paulos Eyassu 43 Male Sawa Camp 9/24/1994 Conscientious Objection Isaac Mogos 41 Male Sawa Camp 9/24/1994 Conscientious Objection Negede Teklemariam 40 Male Sawa Camp 9/24/1994 Conscientious Objection Aron Abraha 42 Male Sawa Camp 5/9/2001 Conscientious Objection Mussie Fessehaya 44 Male Sawa Camp 6/2003 Conscientious Objection Ambakom Tsegezab 41 Male Sawa Camp 2/2004 Conscientious Objection Bemnet Fessehaye 44 Male Sawa Camp 2/2005 Conscientious Objection Henok Ghebru 32 Male Sawa Camp 2/2005 Conscientious Objection Worede Kiros 59 Male Sawa Camp 5/4/2005 Religious Activity Yonathan Yonas 30 Male Sawa Camp 11/12/2005 Religious Activity Kibreab Fessehaye 38 Male Sawa Camp 12/27/2005 Conscientious Objection Bereket Abraha Oqbagabir 46 Male Sawa Camp 1/1/2006 Conscientious Objection Yosief Fessehaye 27 Male Sawa Camp 2007 Conscientious Objection Mogos Gebremeskel 68 Male Adi-Abieto 7/3/2008 Unknown Bereket Abraha 67 Male Meitir Camp 7/8/2008 Unknown Ermias Ashgedom 25 Male Meitir Camp 7/11/2008 Unknown Habtemichael Mekonen 74 Male Meitir Camp 7/17/2008 Unknown Tareke Tesfamariam 64 Male Meitir Camp 8/4/2008 Unknown Goitom Aradom 72 Male Meitir Camp 8/8/2008 Unknown Habtemichael Tesfamariam 67 Male Meitir Camp 8/8/2008 Unknown Tewoldemedhin Habtezion 57 Male Meitir Camp 8/9/2008 Unknown Teferi Beyene 73 Male Meitir Camp 9/23/2008 Unknown Beyene Abraham 63 Male Karen Police Station 10/23/2008 Unknown Asfaha -

Basic Information Living Standards

BASIC INFORMATION LIVING STANDARDS SURVEY IN THE REPUBLIC OF TAJIKISTAN (TLSS) JUNE 2000 PRINCIPAL ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS USED CIS Commonwealth of Independent States FSU Former Soviet Union LSE London School of Economics LSMS Living Standard Measurement Survey PP Population point RRS Rayons of Republican Subordination SSA State Statistical Agency TLSS Tajik Living Standard Survey UNDP United Nations Development Programme UTO United Tajik Opposition TR Tajik Roubles WB The World Bank This report was prepared as part of an expanded program of documentation and further development of the Living Standards Measurement Study (LSMS) managed by Kinnon Scott in the Poverty and Human Resources Division of the Development Research Group (DECRG). It was written by Ceema Namazie, Consultant, London School of Economics. Substantial contributions were provided by Jane Falkingham, Consultant, London School of Economics; Mr Tureav, Deputy Chairman State Statistical Agency, The Republic of Tajikistan; Mr Firuz Saidov, National Project Manager, Centre for Strategic Studies, The Republic of Tajikistan; and Annelies Drost (ECSHD). Comments were provided by Diane Steele (DECRG). 2 Table of Contents INTRODUCTION................................................................................................................................................ 2 GEOGRAPHICAL OVERVIEW................................................................................................................................. 2 FIELD WORK .................................................................................................................................................... -

ASEAN Workshop on Election Observation

Report from the 2015 ASEAN Workshop on Election Observation Election on ASEAN Workshop 2015 the from Report ASEAN Workshop on Election Observation Incremental Steps Towards the Establishment of an ASEAN Election Observation Mechanism Manila, 24–25 June 2015 Funded by International IDEA ASEAN-ROK Special Cooperation Fund SE -103 34 Stockholm Sweden Phone + 46 8 698 37 00 Fax + 46 8 20 24 22 E-mail: [email protected] Website: http://www.idea.int ASEAN Workshop on Election Observation Incremental Steps Towards the Establishment of an ASEAN Election Observation Mechanism Manila, 24–25 June 2015 Funded by ASEAN-ROK Special Cooperation Fund Writer Sanjay Gathia Content Editors Andrew Ellis Adhy Aman International IDEA resource on the ASEAN election observation mechanism Copyright © 2015 International IDEA Strömsborg, SE - 103 34, Stockholm, Sweden Tel: +46 8 698 37 00 Fax: +46 8 20 24 22 Email: [email protected] Website: www.idea.int International IDEA publications are independent of specific national or political interests. Views expressed in this publication do not necessarily represent the views of International IDEA, its Board or its Council members. Cover photograph courtesy of the Department of Foreign Affairs of the Philippines Foreword The commitment of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) to the principle of ‘adherence to the rule of law, good governance, democracy and constitutional government‘, is becoming increasingly relevant in the evolving and complex political landscape of the region, where democracy is being constantly challenged. The region’s democratic journey has been rather uneven and full of obstacles, although not for lack of commitment and determination. -

CORI Country Report Uzbekistan, November 2010

CORI country of origin research and information CORI Country Report Uzbekistan, November 2010 Commissioned by the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). Any views expressed in this paper are those of the author and are not necessarily those of UNHCR. Preface Country of Origin Information (COI) is required within Refugee Status Determination (RSD) to provide objective evidence on conditions in refugee producing countries to support decision making. Quality information about human rights, legal provisions, politics, culture, society, religion and healthcare in countries of origin is essential in establishing whether or not a person’s fear of persecution is well founded. CORI Country Reports are designed to aid decision making within RSD. They are not intended to be general reports on human rights conditions. They serve a specific purpose, collating legally relevant information on conditions in countries of origin, pertinent to the assessment of claims for asylum. Categories of COI included within this report are based on the most common issues arising from asylum applications made by Uzbekistan nationals. This report covers events up to 30 November 2010. COI is a specific discipline distinct from academic, journalistic or policy writing, with its own conventions and protocols of professional standards as outlined in international guidance such as The Common EU Guidelines on Processing Country of Origin Information, 2008 and UNHCR, Country of Origin Information: Towards Enhanced International Cooperation, 2004. CORI provides information impartially and objectively, the inclusion of source material in this report does not equate to CORI agreeing with its content or reflect CORI’s position on conditions in a country. -

World Bank Document

Ministry of Agriculture and Uzbekistan Agroindustry and Food Security Agency (UZAIFSA) Public Disclosure Authorized Uzbekistan Agriculture Modernization Project Public Disclosure Authorized ENVIRONMENTAL AND SOCIAL MANAGEMENT FRAMEWORK Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Tashkent, Uzbekistan December, 2019 ABBREVIATIONS AND GLOSSARY ARAP Abbreviated Resettlement Action Plan CC Civil Code DCM Decree of the Cabinet of Ministries DDR Diligence Report DMS Detailed Measurement Survey DSEI Draft Statement of the Environmental Impact EHS Environment, Health and Safety General Guidelines EIA Environmental Impact Assessment ES Environmental Specialist ESA Environmental and Social Assessment ESIA Environmental and Social Impact Assessment ESMF Environmental and Social Management Framework ESMP Environmental and Social Management Plan FS Feasibility Study GoU Government of Uzbekistan GRM Grievance Redress Mechanism H&S Health and Safety HH Household ICWC Integrated Commission for Water Coordination IFIs International Financial Institutions IP Indigenous People IR Involuntary Resettlement LAR Land Acquisition and Resettlement LC Land Code MCA Makhalla Citizen’s Assembly MoEI Ministry of Economy and Industry MoH Ministry of Health NGO Non-governmental organization OHS Occupational and Health and Safety ОP Operational Policy PAP Project Affected Persons PCB Polychlorinated Biphenyl PCR Physical Cultural Resources PIU Project Implementation Unit POM Project Operational Manual PPE Personal Protective Equipment QE Qishloq Engineer -

Usaid Family Farming Program Tajikistan

USAID FAMILY FARMING PROGRAM TAJIKISTAN ANNEX 6 TO QUARTERLY REPORT: TRAINING REPORT JANUARY-MARCH 2014 APRIL 30, 2014 This annex to annual report is made possible by the support of the American people through the United States Agency for International Development (USAID). The contents are the sole responsibility of DAI and do not necessarily reflect the views of USAID or the United States Government. USAID FAMILY FARMING PROGRAM ANNEX 6 TO QUARTERLY REPORT: TRAINING REPORT JANUARY- MARCH 2014 Program Title: USAID Family Farming Program for Tajikistan Sponsoring USAID Office: Economic Growth Office Chief of Party: James Campbell Contracting Officer Kerry West Contracting Officer Representative Aviva Kutnick Contract Number: EDH-I-00-05-00004, Task Order: AID-176-TO-10-00003 Award Period: September 30, 2010 through September 29, 2014 Contractor: DAI Subcontractors: Winrock International Date of Publication: April 30, 2014 Author: Ilhom Azizov, Training Coordinator The authors’ views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect the views of the United States Agency for International Development or the United States Government. CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ..................................................................................................... 2 SUMMARY ........................................................................................................................... 3 TRAINING OBJECTIVES ............................................................................................................3 METHODS OF -

Univer^ Micrèïilms International 300 N

INFORMATION TO USERS This was produced from a copy of a document sent to us for microfilming. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the material submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or notations which may appear on this reproduction. 1.The sign or “target” for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is “Missing Page(s)”. If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting through an image and duplicating adjacent pages to assure you of complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a round black mark it is an indication that the film inspector noticed either blurred copy because of movement during exposure, or duplicate copy. Unless we meant to delete copyrighted materials that should not have been filmed, you will find a good image of the page in the adjacent frame. If copyrighted materials were deleted you will find a target note listing the pages in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing or chart, etc., is part of the material being photo graphed the photographer has followed a definite method in “sectioning” the material. It is customary to begin filming at the upper left hand corner of a large sheet and to continue from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. If necessary, sectioning is continued again—beginning below the first row and continuing on until complete. -

Usaid Family Farming Program Tajikistan

USAID FAMILY FARMING PROGRAM TAJIKISTAN ANNEX 9 TO QUARTERLY REPORT: TRAINING REPORT APRIL - JUNE 2014 JULY 25, 2014 This annex to annual report is made possible by the support of the American people through the United States Agency for International Development (USAID). The contents are the sole responsibility of DAI and do not necessarily reflect the views of USAID or the United States Government. USAID FAMILY FARMING PROGRAM ANNEX 5 TO QUARTERLY REPORT: TRAINING REPORT APRIL – JUNE 2014 Program Title: USAID Family Farming Program for Tajikistan Sponsoring USAID Office: Economic Growth Office Chief of Party: James Campbell Contracting Officer Kerry West Contracting Officer Representative Aviva Kutnick Contract Number: EDH-I-00-05-00004, Task Order: AID-176-TO-10-00003 Award Period: September 30, 2010 through September 29, 2014 Contractor: DAI Subcontractors: Winrock International Date of Publication: July 25, 2014 Author: Ilhom Azizov, Training Coordinator The authors’ views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect the views of the United States Agency for International Development or the United States Government. CONTENTS SUMMARY ........................................................................................................................... 2 TRAINING OBJECTIVES............................................................................................................ 2 METHODS OF TRAINING ........................................................................................................... 2 TRAINING -

Central Asia, August 2002

Description of document: US Department of State Self Study Guide for Central Asia, August 2002 Requested date: 11-March-2007 Released date: 25-Mar-2010 Posted date: 19-April-2010 Source of document: Freedom of Information Act Office of Information Programs and Services A/GIS/IPS/RL U. S. Department of State Washington, D. C. 20522-8100 Fax: 202-261-8579 Note: This is one of a series of self-study guides for a country or area, prepared for the use of USAID staff assigned to temporary duty in those countries. The guides are designed to allow individuals to familiarize themselves with the country or area in which they will be posted. The governmentattic.org web site (“the site”) is noncommercial and free to the public. The site and materials made available on the site, such as this file, are for reference only. The governmentattic.org web site and its principals have made every effort to make this information as complete and as accurate as possible, however, there may be mistakes and omissions, both typographical and in content. The governmentattic.org web site and its principals shall have neither liability nor responsibility to any person or entity with respect to any loss or damage caused, or alleged to have been caused, directly or indirectly, by the information provided on the governmentattic.org web site or in this file. The public records published on the site were obtained from government agencies using proper legal channels. Each document is identified as to the source. Any concerns about the contents of the site should be directed to the agency originating the document in question. -

Ukrainian Women in Тне Soviet Union

UKRAINIAN WOMEN IN ТНЕ SOVIET UNION 1975-1980 COMPILED ВУ NINA STROKATA diasporiana.org.ua DOCUMENTS OF UKRAINIAN SAMVYDAV UKRAINIAN WOMEN IN ТНЕ SOVIET UNION DOCUMENTED PERSECUTION Compiled Ьу Nina Strokata Translated and edited Ьу Myroslava Stefaniuk and Volodymyr Hruszkewych SMOLOSKYP SAMVYDAV SERIES No. 7 SMOLOSKYP PUBLISHERS 1980 Baltlmore- Toronto DOCUMENTS OF UKRAINIAN SAMVYDAV Smoloskyp Samvydav Serles No. 7, 1980 UKRAINIAN WOMEN IN ТНЕ SOVIET UNION DOCUMENTED PERSECUTION Copyright © 1980 Ьу Nina Strokata and Smoloskyp, Inc. ISBN: 0-91834-43-6 Published Ьу Smoloskyp Publishers, Smoloskyp, lnc. SMOLOSKYP Р.О. Вох 561 Ellicott City, Md. 210~3. USA Net royaltles wlll Ье used ln the lntereet of Ukralnlan polltlcal prlsone,. ln the USSR Printed in the United States of America Ьу ТНЕ HOLLIDA У PRESS. INC. CONTENTS Preface 7 М. Landa, Т. Khodorovich, An.Appeal to Medical Doctors of the World, in Defense of Nina Strokata, October 20-23, 1976 11 N. Strokata, М. Landa to the International Federation of Participants in the Resistance Movement, October 1976 19 N. Svitlychna to the Ukrainian Public Group to Promote the lmplementation of the Helsinki Accords, December 10, 1976 21 S. Shabatura to the Attorney General of the USSR 27 N. Strokata-Karavanska, S. Shabatura to Ukrainians of the American Continent 33 О. Meshko to the Belgrade Conference Reviewing the lmplementation of the Helsinki Accords 37 N. Strokata-Karavanska to thє Authors of the Draft of the Soviet Constitution-77, September, 1977 41 S. Shabatura to the Head of the GUITU, February 24, 1978 45 V. Sira to the Citizens of the West 49 О. -

Download the Report

November 1993 Vol. 5, Issue 21 TTTHREATS TO PPPRESS FFFREEDOMS A Report Prepared for the Free Media Seminar Commission on Security and Cooperation in Europe TTTABLE OF CCCONTENTS Introduction....................................................................................................................................................................................................................1 Croatia...............................................................................................................................................................................................................................3 Hungary..............................................................................................................................................................................................................................7 Poland..............................................................................................................................................................................................................................10 Romania..........................................................................................................................................................................................................................14 Russia .............................................................................................................................................................................................................................. 17