Fluctuations in the Painting Production in the 17Th-Century Netherlands

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

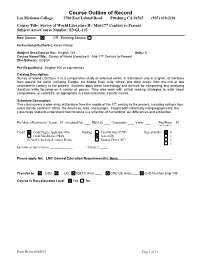

Course Outline of Record Los Medanos College 2700 East Leland Road Pittsburg CA 94565 (925) 439-2181

Course Outline of Record Los Medanos College 2700 East Leland Road Pittsburg CA 94565 (925) 439-2181 Course Title: Survey of World Literature II: Mid-17th Century to Present Subject Area/Course Number: ENGL-145 New Course OR Existing Course Instructor(s)/Author(s): Karen Nakaji Subject Area/Course No.: English 145 Units: 3 Course Name/Title: Survey of World Literature II: Mid-17th Century to Present Discipline(s): English Pre-Requisite(s): English 100 or equivalency Catalog Description: Survey of World Literature II is a comparative study of selected works, in translation and in English, of literature from around the world, including Europe, the Middle East, Asia, Africa, and other areas, from the mid or late seventeenth century to the present. Students apply basic terminology and devices for interpreting and analyzing literature while focusing on a variety of genres. They also work with critical reading strategies to write about comparisons, or contrasts, as appropriate in a baccalaureate, transfer course. Schedule Description: This class covers a wide array of literature from the middle of the 17th century to the present, including authors from every literate continent: Africa, the Americas, Asia, and Europe. Taught both historically and geographically, the class helps students understand how literature is a reflection of humankind, our differences and similarities. Hrs/Mode of Instruction: Lecture: 54 Scheduled Lab: ____ HBA Lab: ____ Composition: ____ Activity: ____ Total Hours 54 (Total for course) Credit Credit Degree Applicable -

London and Middlesex in the 1660S Introduction: the Early Modern

London and Middlesex in the 1660s Introduction: The early modern metropolis first comes into sharp visual focus in the middle of the seventeenth century, for a number of reasons. Most obviously this is the period when Wenceslas Hollar was depicting the capital and its inhabitants, with views of Covent Garden, the Royal Exchange, London women, his great panoramic view from Milbank to Greenwich, and his vignettes of palaces and country-houses in the environs. His oblique birds-eye map- view of Drury Lane and Covent Garden around 1660 offers an extraordinary level of detail of the streetscape and architectural texture of the area, from great mansions to modest cottages, while the map of the burnt city he issued shortly after the Fire of 1666 preserves a record of the medieval street-plan, dotted with churches and public buildings, as well as giving a glimpse of the unburned areas.1 Although the Fire destroyed most of the historic core of London, the need to rebuild the burnt city generated numerous surveys, plans, and written accounts of individual properties, and stimulated the production of a new and large-scale map of the city in 1676.2 Late-seventeenth-century maps of London included more of the spreading suburbs, east and west, while outer Middlesex was covered in rather less detail by county maps such as that of 1667, published by Richard Blome [Fig. 5]. In addition to the visual representations of mid-seventeenth-century London, a wider range of documentary sources for the city and its people becomes available to the historian. -

Augustus 2013 | E 4,95

19de jaargang | nummer 5 | augustus 2013 | e 4,95 Goudende eeuw in Friesland 1 FR_GG.indd 1 22-07-13 11:00 INHOUD De 19de jaargang | nummer 5 | augustus 2013 Gouden Eeuw in Friesland 42 4 10 6 36 58 4 Eigenzinnig en WElvaart, status En knappE koppEn kunst En Cultuur lanDsCHap En enerverend pronk 28 De Franeker universiteit 38 Lijnen van De Geest en EConoMIE Yme KUIper 10 Nieuw geld, nieuwe elite gOffe JeNSma lambert Jacobsz 54 Dynamiek en expansie HOtSO SpaNNINga 31 Winsemius en de geleerde pIet baKKer meINDert ScHrOOr 6 ‘Ik wil geschiedenis 13 Smullen en schransen wereld 42 Het verlanglijstje van het 58 Friesland en de voC levend en leerzaam rUUD SprUIt arJeN DIJKStra Fries Genootschap femme gaaStra maken’ 17 De zilveren positie van 32 Vrij van geweten, niet marlIeS StOter 62 De semskaart van Hans Goedkoop over de Friese nassaus van uitoefening 44 Burgertrots in steen leeuwarden De Gouden Eeuw JOOp W. KOOpmaNS WIebe bergSma peter KarStKarel meINDert ScHrOOr Yme KUIper eN 20 Wybrand de Geest, 35 Een platte hemel 48 Schrijvers en lezers 64 In aventoerlik man SIebraND KrUl portretkunstenaar arJeN DIJKStra pHIlIppUS breUKer DOeKe SIJeNS rUDI eKKart 36 Homo universalis: anna 52 De culturele industrie 66 De Zijl van Dokkum 22 Crack en zijn connecties Maria van schurman Harm NIJbOer HaNS KOppeN Yme KUIper mIrJam De baar 68 De Friese vaart op de 24 De raadselachtige oostzee en noorwegen dr. popta HaNNO braND Yme KUIper 71 Een aristocratische graanrepubliek KeeS KUIKeN cOlOfON vormgeving Druk verlengd. lidmaatschap Koninklijk fries genootschap Historisch tijdschrift Fryslân is een uitgave van het Koninklijk frank de Wit Ten brink, postbus 41, (Historisch tijdschrift Fryslân plus Jaarboek De Vrije Fries plus fries genootschap voor geschiedenis en cultuur/Keninklik 7940 aa meppel ledenvoordelen) ? 42,50 frysk genoatskip foar Skiednis en Kultuer. -

05237353.Pdf

MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY Center for International Studies C/65-20 July 10, 1965 THE REVIVAL OF EAST EUROPEAN NATIONALIEMS William E. Griffith Prepared for the Fifth International Conference on World Politics Noordwijk, Netherlands September 13-18, 1965 MuM mrsm - - m- -io m - m THE REVIVAL OF EAST EUROPEAN NATIONALISMS The slow but sure revival of nationalism in Eastern Europe can best be analyzed by considering its two major causes. first, changes in external influences and, second, domestic developments. T The primary external influence in Eastern Europe remains the Soviet Union. One of the resualts of the Second World War was that Eastern Europe fell into the Soviet sphere of influence; and, al- though to a lesser extent, it continues there until this day. At first, under Stalin, Eastern Europe increasingly became something close to a part of the Soviet Union. One of the tasks of his suc- cessors was to begin an imperial readjustment, in which Eastern Europe was the lesser problem; China, we now know, was the major one. Paradoxically, it was largely not in spite of but because of the 1956 Polish October and Hungarian Revolution that by the late nineteen fifties Jrushchev seemed. to be doing quite well in Eastern Europe. (We did not know then what we do now: he was already doing badly with China,) Khrushchev's program of de-Stalinization probably strengthened the Communist regime, at least for the pres- ent, within the Soviet Union, and it to some extent helped the Soviet Union in Eastern Europe. (For example, between 1953 -

Reading the Remains of the 17Th Century

AnthroNotes Volume 28 No. 1 Spring 2007 WRITTEN IN BONE READING THE REMAINS OF THE 17TH CENTURY by Kari Bruwelheide and Douglas Owsley ˜ ˜ ˜ [Editor’s Note: The Smithsonian’s Department of Anthro- who came to America, many willingly and others under pology has had a long history of involvement in forensic duress, whose anonymous lives helped shaped the course anthropology by assisting law enforcement agencies in the of our country. retrieval, evaluation, and analysis of human remains for As we commemorate the 400th anniversary of the identification purposes. This article describes how settlement of Jamestown, it is clear that historians and ar- Smithsonian physical anthropologists are applying this same chaeologists have made much progress in piecing together forensic analysis to historic cases, in particular seventeenth the literary records and artifactual evidence that remain from century remains found in Maryland and Virginia, which the early colonial period. Over the past two decades, his- will be the focus of an upcoming exhibition, Written in Bone: torical archaeology especially has had tremendous success Forensic Files of the 17th Century, scheduled to open at the in charting the development of early colonial settlements Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History in No- through careful excavations that have recovered a wealth vember 2008. This exhibition will cover the basics of hu- of 17th century artifacts, materials once discarded or lost, man anatomy and forensic investigation, extending these and until recently buried beneath the soil (Kelso 2006). Such techniques to the remains of colonists teetering on the edge discoveries are informing us about daily life, activities, trade of survival at Jamestown, Virginia, and to the wealthy and relations here and abroad, architectural and defensive strat- well-established individuals of St. -

Julius S. Held Papers, Ca

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt3g50355c No online items Finding aid for the Julius S. Held papers, ca. 1921-1999 Isabella Zuralski. Finding aid for the Julius S. Held 990056 1 papers, ca. 1921-1999 Descriptive Summary Title: Julius S. Held papers Date (inclusive): ca. 1918-1999 Number: 990056 Creator/Collector: Held, Julius S (Julius Samuel) Physical Description: 168 box(es)(ca. 70 lin. ft.) Repository: The Getty Research Institute Special Collections 1200 Getty Center Drive, Suite 1100 Los Angeles 90049-1688 [email protected] URL: http://hdl.handle.net/10020/askref (310) 440-7390 Abstract: Research papers of Julius Samuel Held, American art historian renowned for his scholarship in 16th- and 17th-century Dutch and Flemish art, expert on Peter Paul Rubens, Anthony van Dyck, and Rembrandt. The ca. 70 linear feet of material, dating from the mid-1920s to 1999, includes correspondence, research material for Held's writings and his teaching and lecturing activities, with extensive travel notes. Well documented is Held's advisory role in building the collection of the Museo de Arte de Ponce in Puerto Rico. A significant portion of the ca. 29 linear feet of study photographs documents Flemish and Dutch artists from the 15th to the 17th century. Request Materials: Request access to the physical materials described in this inventory through the catalog record for this collection. Click here for the access policy . Language: Collection material is in English Biographical / Historical Note The art historian Julius Samuel Held is considered one of the foremost authorities on the works of Peter Paul Rubens, Anthony van Dyck, and Rembrandt. -

Medieval Or Early Modern

Medieval or Early Modern Medieval or Early Modern The Value of a Traditional Historical Division Edited by Ronald Hutton Medieval or Early Modern: The Value of a Traditional Historical Division Edited by Ronald Hutton This book first published 2015 Cambridge Scholars Publishing Lady Stephenson Library, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2PA, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2015 by Ronald Hutton and contributors All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-4438-7451-5 ISBN (13): 978-1-4438-7451-9 CONTENTS Chapter One ................................................................................................. 1 Introduction Ronald Hutton Chapter Two .............................................................................................. 10 From Medieval to Early Modern: The British Isles in Transition? Steven G. Ellis Chapter Three ............................................................................................ 29 The British Isles in Transition: A View from the Other Side Ronald Hutton Chapter Four .............................................................................................. 42 1492 Revisited Evan T. Jones Chapter Five ............................................................................................. -

Die Schaede Is Soo Groot Ende Excessyff' '

‘Die schaede is soo groot ende excessyff’ Maatregelen tegen geweld en geweldsdreiging op de Europese zeehandelsroutes van de Republiek, 1600-1630 Liesbeth Sparks 1 Scriptie Vroegmoderne Geschiedenis - Universiteit Utrecht - 3-7-2008 - Student: 0042498 - Begeleider: Oscar Gelderblom 2 Voor Madelief 3 4 Inhoudsopgave Voorwoord 9 Lijst van tabellen 11 Inleiding 13 H1 De handel van de Republiek in Europa 1580-1650 18 1. Oorzaken voor de Nederlandse handelsexpansie 1580-1620 19 2. Belangrijkste Europese handelsroutes 23 2.1 De Oostzeevaart 24 2.2 De westvaart 29 2.3 De straatvaart 31 3. Concluderend 33 H2 Geweldsrisico’s voor de Nederlandse handel in Europa 1600-1630 36 1. Theorie: relatie tussen geweld en staatsversterking 36 2. Staatsgeweld: militair 38 2.1 Indirect militair geweld: Baltisch gebied 39 2.2 Direct militair geweld: Spanje 41 3. Staatsgeweld: economisch 42 3.1 Economische dreiging: Baltisch gebied 42 3.2 Economische oorlogvoering: Spanje 44 4. Gedelegeerd staatsgeweld: kaapvaart 50 4.1 Duinkerkse kapers 51 4.2 Spaanse kapers 56 4.3 Kaapvaart in de Oostzee 57 5 5. Buitenstatelijk geweld: zeeroof 58 5.1 Engelse piraten 59 5.2 Geval apart: Barbarije 62 6. Concluderend 64 H3 Publieke oplossingen voor geweldsrisico’s: preventie 67 1. Oplossingen voor geweld: preventie of compensatie? 67 2. ‘Defensieve’ preventie: konvooiering, patrouilles en bewapening 69 2.1 Konvooisysteem en patrouilles 69 2.2 Verplichte bewapening 74 3. ‘Offensieve’ preventie: van diplomatie tot militaire actie 75 3.1 Diplomatie 75 3.2 Politieke druk en militaire dreiging 81 Baltisch gebied: politieke allianties en militaire dreiging 81 Duinkerkse kapers: politieke druk 83 3.3 Militaire actie 84 Duinkerkse kapers: Blokkade en militaire expedities 85 Engelse zeerovers: Nederlandse oorlogsschepen op jacht 90 Spanje: galeien en andere militaire acties 91 Barbarijse zeerovers: strafexpedities 94 H4 Private oplossingen voor geweldsrisico’s: compensatie en preventie 98 1. -

DALMI WORKING PAPERS on ART & MARKETS the Artistic Migration

DALMI Working Paper No. 15231 DALMI WORKING PAPERS ON ART & MARKETS The Artistic Migration Between Mechelen and Delft (1550–1625) Fiene Leunissen Working Paper no. 15231 https://www.dukedalmi.org/wp-content/uploads/15231-Working-Paper.pdf DUKE ART, LAW & MARKETS INITIATIVE 114 S. Buchanan Blvd. Campus Box 90766 Durham, NC 27708 May 2015 DALMI working papers are circulated for discussion and comment purposes. They have not been peer-reviewed. © 2015 by Fiene Leunissen. All rights reserved. Leunissen May 2015 DALMI Working Paper No. 15231 The Artistic Migration Between Mechelen and Delft (1550–1625) Fiene Leunissen DALMI Working Paper No. 15231 May 2015 ABSTRACT Mechelen (Malines) is a small city in present-day Belgium, positioned between Antwerp and Brussels, along the river the Dijle. While most people today have never heard anything about this city or its history, this small town was once one of the most important cities in the Low Countries. It was also hub for the production of watercolor paintings. During the religious turmoil in the second half of the 16th century a large portion of artists fled the city to find a better life in other European cities. One of these places was Delft, were a group of 24 Mechelen artists settled. In this paper we look at the lives of these artists to better understand the knowledge circulation between the north and the south at the turn of the 17th century. Keywords: Art Markets, Mechelen, Delft, Seventeenth Century JEL: Z11 Leunissen May 2015 DALMI Working Paper No. 15231 Leunissen May 2015 DALMI Working Paper No. -

The Southern Colonies in the 17Th and 18Th Centuries

AP U.S. History: Unit 2.1 Student Edition The Southern Colonies in the 17th and 18th Centuries I. Southern plantation colonies: general characteristics A. Dominated to a degree by a plantation economy: tobacco and rice B. Slavery in all colonies (even Georgia after 1750); mostly indentured servants until the late-17th century in Virginia and Maryland; increasingly black slavery thereafter C. Large land holdings owned by aristocrats; aristocratic atmosphere (except North Carolina and parts of Georgia in the 18th century). D. Sparsely populated: churches and schools were too expensive to build for very small towns. E. Religious toleration: the Church of England (Anglican Church) was the most prominent F. Expansionary attitudes resulted from the need for new land to compensate for the degradation of existing lands from soil-depleting tobacco farming; this expansion led to conflicts with Amerindians. II. The Chesapeake (Virginia and Maryland) A. Virginia (founded in 1607 by the Virginia Company) 1. Jamestown, 1607: 1st permanent British colony in New World a. Virginia Company: joint-stock company that received a charter from King James I in 1606 to establish settlements in North America. Main goals: Promise of gold, conversion of Amerindians to Christianity (like Spain had done), and new passage through North America to the East Indies (Northwest Passage). Consisted largely of well-to-do adventurers. b. Virginia Charter Overseas settlers were given same rights of Englishmen in England. Became a foundation for American liberties; similar rights would be extended to other North American colonies. 2. Jamestown was wracked by tragedy during its early years: famine, disease, and war with Amerindians a. -

British Pamphlets, 17Th Century

British Pamphlets, 17th Century Court of Honour, or, The Vertuous Protestant’s Looking Glass. 1679. Case Y 194 .785. The Newberry has more than 2,200 pamphlets published in Great Britain during the Stuart period (1600-1715). The subjects covered in these pamphlets are varied and include the Civil War, Church of England doctrines, Acts of Parliament, and the Popish Plot. There are collections of pamphlets about the Stuart era monarchs as well as Cromwellian pamphlets. There are pamphlets in the form of letters, sermons, political verse, and drama. Authors include Defoe, Hobbes, Swift, Milton, Pepys. While the collection is rich, finding pamphlets can be a challenge. Searching the Online Catalog The online catalog is the best place to start your search for seventeenth century British pamphlets. If you know the title or author of a given pamphlet, try searching under those headings to start. Many pamphlets are bound with pamphlets of similar themes, so it can be difficult to find individual pamphlets by title or author. Often subject searches retrieve the largest number of relevant pamphlets. A variety of different subject headings are used in the online catalog. They follow the following patterns: Great Britain—History—[range of years]—Pamphlets Example: Great Britain History 1660-1688 Pamphlets Great Britain—Politics and Government—[range of years]—Pamphlets Example: Great Britain Politics and Government 1603-1714 Pamphlets Great Britain—History—[name of monarch]—Pamphlets Example: Great Britain History Charles II Pamphlets In the cases where pamphlets cannot be found using these searches, try the “Advanced Search” option, and set limits on the language and year(s) of publication. -

17Th Century Weston (PDF)

A Weston Timeline (Taken from Farm Town to Suburb: the History and Architecture of Weston, Massachusetts, 1830-1980 by Pamela W. Fox, 2002) Map of the Watertown Settlement (from Genealogies of the Families and Descendants of the Early Settlers of Watertown, Massachusetts. Vol 1, by Henry Bond, M.D. 17th CENTURY 1630 Sir Richard Saltonstall and Rev. George Phillips lead a company up the Charles River to establish the settlement of Watertown, which included what is now Watertown, Waltham, Weston, and parts of several adjoining towns. Weston was known as Watertown Farms or the Farm Lands. Below: Sir Richard Saltonstall 1642 First allotments of land in the Farm Lands. Settlers used the land primarily for grazing cattle. 1673 Approximate time when farmers began to take up residence in what is now Weston. On Sundays, they traveled nearly seven miles from The Farms to the Watertown church. 1673 First post rider is dispatched from New York City to Boston, traveling over mostly Indian trails. Weston was located on the Upper Road, the most popular of three “post roads” used by travelers. 1679 Richard Child establishes a gristmill at Stony Brook near what is now the Waltham town line. Later a sawmill at the same location was used to saw timber for the early houses of Weston. 1695 Weston farmers begin building their own crude, 30-foot-square “Farmers’ Meeting House.” c. 1696 One Chestnut Street House has long been considered the oldest house remaining in Weston. The house was originally “one over one” room. 1698 The General Court grants settlers their formal petition to establish a separate Farmers’ Precinct, also referred to as the Third Military Precinct, the precinct of Lt.