Arthur Schnitzler

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

LA RONDE EXPLORES PSYCHOLOGICAL DANCE of RELATIONSHIPS New Professor Brings Edgy Movement to Freudian-Inspired Play

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE: January 30, 2009 PASSION, POWER & SEDUCTION – LA RONDE EXPLORES PSYCHOLOGICAL DANCE OF RELATIONSHIPS New professor brings edgy movement to Freudian-inspired play. 2008/2009 Season What better time to dissect the psychology of relationships and human sexuality than just after Valentine’s Day? 3 LA RONDE Where better than at the University of Victoria Phoenix Theatre's production of La Ronde, February 19 to 28, 2009. February 19 – 28, 2009 By Arthur Schnitzler Steeped in the struggles of psychology, sex, relationships and social classes, Arthur Schnitzler's play La Ronde, Direction: Conrad Alexandrowicz th Set & Lighting Design: Paphavee Limkul (MFA) written in 1897, explores ten couples in Viennese society in the late 19 century. Structured like a round, in music or Costume Design: Cat Haywood (MFA) dance, La Ronde features a cast of five men and five women and follows their intricately woven encounters through Stage Manager: Lydia Comer witty, innuendo-filled dialogue. From a soldier and a prostitute, to an actress and a count, their intimate A psychological dance of passion, power and relationships transcend social and economic status to comment on the sexual mores of the day. Schnitzler himself seduction through Viennese society in the 1890s. was no stranger to such curiosities. A close friend of Sigmund Freud, Schnitzler was considered Freud's creative Advisory: Mature subject matter, sexual equivalent. He shared Freud’s fascination with sex: historians have noted that he began frequenting prostitutes at content. age sixteen and recording meticulously in his diary an analysis of every orgasm he achieved! Recently appointed professor of acting and movement, director Conrad Alexandrowicz gives La Ronde a contemporary twist while maintaining the late 19th century period of the play. -

Shattering Fragility: Illness, Suicide, and Refusal in Fin-De-Siècle Viennese Literature

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 2013 Shattering Fragility: Illness, Suicide, and Refusal in Fin-De-Siècle Viennese Literature Melanie Jessica Adley University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Part of the German Literature Commons, and the Women's Studies Commons Recommended Citation Adley, Melanie Jessica, "Shattering Fragility: Illness, Suicide, and Refusal in Fin-De-Siècle Viennese Literature" (2013). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 729. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/729 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/729 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Shattering Fragility: Illness, Suicide, and Refusal in Fin-De-Siècle Viennese Literature Abstract How fragile is the femme fragile and what does it mean to shatter her fragility? Can there be resistance or even strength in fragility, which would make it, in turn, capable of shattering? I propose that the fragility embodied by young women in fin-de-siècle Vienna harbored an intentionality that signaled refusal. A confluence of factors, including psychoanalysis and hysteria, created spaces for the fragile to find a voice. These bourgeois women occupied a liminal zone between increased access to opportunities, both educational and political, and traditional gender expectations in the home. Although in the late nineteenth century the femme fragile arose as a literary and artistic type who embodied a wan, ethereal beauty marked by delicacy and a passivity that made her more object than authoritative subject, there were signs that illness and suicide could be effectively employed to reject societal mores. -

A Selective Study of the Writings of Kafka, Kubin, Meyrink, Musil and Schnitzler

_________________________________________________________________________Swansea University E-Theses The literary dream in German Central Europe, 1900-1925: A selective study of the writings of Kafka, Kubin, Meyrink, Musil and Schnitzler. Vrba, Marya How to cite: _________________________________________________________________________ Vrba, Marya (2011) The literary dream in German Central Europe, 1900-1925: A selective study of the writings of Kafka, Kubin, Meyrink, Musil and Schnitzler.. thesis, Swansea University. http://cronfa.swan.ac.uk/Record/cronfa42396 Use policy: _________________________________________________________________________ This item is brought to you by Swansea University. Any person downloading material is agreeing to abide by the terms of the repository licence: copies of full text items may be used or reproduced in any format or medium, without prior permission for personal research or study, educational or non-commercial purposes only. The copyright for any work remains with the original author unless otherwise specified. The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holder. Permission for multiple reproductions should be obtained from the original author. Authors are personally responsible for adhering to copyright and publisher restrictions when uploading content to the repository. Please link to the metadata record in the Swansea University repository, Cronfa (link given in the citation reference above.) http://www.swansea.ac.uk/library/researchsupport/ris-support/ The Literary Dream in German Central Europe, 1900-1925 A Selective Study of the Writings of Kafka, Kubin, Meyrink, Musil and Schnitzler Mary a Vrba Thesis submitted to Swansea University in fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Modern Languages Swansea University 2011 ProQuest Number: 10798104 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. -

German (GERM) 1

German (GERM) 1 GERM 2650. Business German. (4 Credits) GERMAN (GERM) Development of oral proficiency used in daily communication within the business world, preparing the students both in technical vocabulary and GERM 0010. German for Study Abroad. (2 Credits) situational usage. Introduction to specialized vocabulary in business and This course prepares students for studying abroad in a German-speaking economics. Readings in management, operations, marketing, advertising, country with no or little prior knowledge of German. It combines learning banking, etc. Practice in writing business correspondence. Four-credit the basics of German with learning more about Germany, and its courses that meet for 150 minutes per week require three additional subtleties and specifics when it comes to culture. It is designed for hours of class preparation per week on the part of the student in lieu of undergraduate and graduate students, professionals and language an additional hour of formal instruction. learners at large, and will introduce the very basics of German grammar, Attribute: IPE. vocabulary, and everyday topics (how to open up a bank account, register Prerequisite: GERM 2001. for classes, how to navigate the Meldepflicht, or simply order food). It GERM 2800. German Short Stories. (4 Credits) aims to help you get ready for working or studying abroad, and better This course follows the development of the short story as a genre in communicate with German-speaking colleagues, family and friends. German literature with particular emphasis on its manifestation as a GERM 1001. Introduction to German I. (5 Credits) means of personal and social integration from the middle of the 20th An introductory course that focuses on the four skills: speaking, reading, century to the present day. -

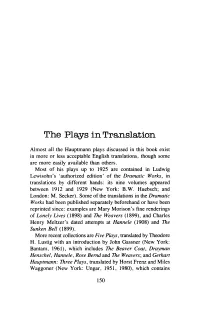

The Plays in Translation

The Plays in Translation Almost all the Hauptmann plays discussed in this book exist in more or less acceptable English translations, though some are more easily available than others. Most of his plays up to 1925 are contained in Ludwig Lewisohn's 'authorized edition' of the Dramatic Works, in translations by different hands: its nine volumes appeared between 1912 and 1929 (New York: B.W. Huebsch; and London: M. Secker). Some of the translations in the Dramatic Works had been published separately beforehand or have been reprinted since: examples are Mary Morison's fine renderings of Lonely Lives (1898) and The Weavers (1899), and Charles Henry Meltzer's dated attempts at Hannele (1908) and The Sunken Bell (1899). More recent collections are Five Plays, translated by Theodore H. Lustig with an introduction by John Gassner (New York: Bantam, 1961), which includes The Beaver Coat, Drayman Henschel, Hannele, Rose Bernd and The Weavers; and Gerhart Hauptmann: Three Plays, translated by Horst Frenz and Miles Waggoner (New York: Ungar, 1951, 1980), which contains 150 The Plays in Translation renderings into not very idiomatic English of The Weavers, Hannele and The Beaver Coat. Recent translations are Peter Bauland's Be/ore Daybreak (Chapel HilI: University of North Carolina Press, 1978), which tends to 'improve' on the original, and Frank Marcus's The Weavers (London: Methuen, 1980, 1983), a straightforward rendering with little or no attempt to convey the linguistic range of the original. Wedekind's Spring Awakening can be read in two lively modem translations, one made by Tom Osbom for the Royal Court Theatre in 1963 (London: Calder and Boyars, 1969, 1977), the other by Edward Bond (London: Methuen, 1980). -

David Hare's the Blue Room and Stanley

Schnitzler as a Space of Central European Cultural Identity: David Hare’s The Blue Room and Stanley Kubrick’s Eyes Wide Shut SUSAN INGRAM e status of Arthur Schnitzler’s works as representative of fin de siècle Vien- nese culture was already firmly established in the author’s own lifetime, as the tributes written in on the occasion of his sixtieth birthday demonstrate. Addressing Schnitzler directly, Hermann Bahr wrote: “As no other among us, your graceful touch captured the last fascination of the waning of Vi- enna, you were the doctor at its deathbed, you loved it more than anyone else among us because you already knew there was no more hope” (); Egon Friedell opined that Schnitzler had “created a kind of topography of the constitution of the Viennese soul around , on which one will later be able to more reliably, more precisely and more richly orient oneself than on the most obese cultural historian” (); and Stefan Zweig noted that: [T]he unforgettable characters, whom he created and whom one still could see daily on the streets, in the theaters, and in the salons of Vienna on the occasion of his fiftieth birthday, even yesterday… have suddenly disappeared, have changed. … Everything that once was this turn-of-the-century Vienna, this Austria before its collapse, will at one point… only be properly seen through Arthur Schnitzler, will only be called by their proper name by drawing on his works. () With the passing of time, the scope of Schnitzler’s representativeness has broadened. In his introduction to the new English translation of Schnitzler’s Dream Story (), Frederic Raphael sees Schnitzler not only as a Viennese writer; rather “Schnitzler belongs inextricably to mittel-Europa” (xii). -

The Figure of the Magister Ludi

Herbert Herzmann Play and Reality in Austrian Drama: The Figure of the Magister Ludi In Calderón de la Barca’s El gran teatro del mundo (The Great Theatre of the World), the Crea- tor/God wishes to see a play performed, and he orders the World to arrange it. He distributes the roles and then watches and judges it. In short, he is a Magister Ludi. The impact of the Baroque tradition, and especially of Calderón’s paradigm, can be detected in many Austrian works for the stage, works which show not only a predilection for a mixture of the emotional and the farcical, but also a strong sense of the theatricality of life, which often leads to a blurring of the borders between play and reality. This chapter concentrates on the function of the Magister Ludi and the relationship between play and reality in Calderón’s El gran teatro del mundo (1633/36), Mo- zart’s Così fan tutte (1790), and Arthur Schnitzler’s Der grüne Kakadu (The Green Cockatoo; 1898) and Felix Mitterer’s In der Löwengrube (In the Lion’s Den; 1998). Felix Mitterer: In der Löwengrube (1998) The Vienna Volkstheater premiered Mitterer’s In der Löwengrube on 24 Jan- uary 1998.1 The plot is based on the true story of a Jewish actor, Leo Reuss, who in 1936 fled from the Nazis in Berlin and went to Austria, where he took on the guise of a Tirolese mountain farmer who claimed to be obsessed with the desire to become an actor. He managed to be interviewed by Max Rein- hardt, who employed him in the Theater in der Josefstadt in Vienna, and he enjoyed a remarkable success. -

The Characterization of the Physician in Schnitzler's and Chekhov's Works

THE PHYSICIAN IN SCHNITZLERIS AND CHEKHOV1S WORKS THE CHARACTERIZATION OF THE PHYSICIAN IN SCHNITZLER 'S Al''-ID CHEKHOV I S WORKS By LOVORKA IVANKA FABEK, B.A. A Thesis Submitted to the School of Graduate Studies in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master Gf Arts McMaster University September 1985 MASTER OF ARTS (1985) McMaster University Hamilton, Ontario TITLE: THE CHARACTERIZATION OF THE PHYSICIAN IN SCHNITZLER'S AND CHEKHOV'S WORKS AUTHOR: LOVORKA IVANKA FABEK, B.A. (McMaster University) SUPERVISOR: Dr. Gerald Chapple NUMBER OF PAGES: viii, 146. ii ABSTRACT Arthur Schnitzler (1862-1931) and Anton Pavlovich Chekhov (1860-1904) were both writers as well as physicians. The latter profession had a significant influence on their works, which is evident in the frequent use of the doctor figure in their plays and prose works. What distinguishes Schnitzler and Chekhov from other writers of the fin-de,...si~c1e, is their ability to clinically observe psycho logical and social problems. Sclmitzler's and Chekhov's works contain "diagnosesJl made by their doctor figure. This study examines the respective qualities of a spectrum of six major types. There are mixed, mainly positive and mainly negative types of doctor figures, ranging from the revolutionary type down to the pathetic doctor figure and the calculating type. Dealing with differences as well as with similarities, the thesis concludes by showing how the characterization of the doctor figure sh.eds light on the authors that created them. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to express my gratitude to my Supervisor, Dr. Gerald Chapple, for initially suggesting the topic of this thesis and for his guidance and advice. -

Sigmund Freud, Arthur Schnitzler, and the Birth of Psychological Man Jeffrey Erik Berry Bates College, [email protected]

Bates College SCARAB Honors Theses Capstone Projects Spring 5-2012 Sigmund Freud, Arthur Schnitzler, and the Birth of Psychological Man Jeffrey Erik Berry Bates College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scarab.bates.edu/honorstheses Recommended Citation Berry, Jeffrey Erik, "Sigmund Freud, Arthur Schnitzler, and the Birth of Psychological Man" (2012). Honors Theses. 10. http://scarab.bates.edu/honorstheses/10 This Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Capstone Projects at SCARAB. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of SCARAB. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Sigmund Freud, Arthur Schnitzler, and the Birth of Psychological Man An Honors Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Departments of History and of German & Russian Studies Bates College In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Arts By Jeffrey Berry Lewiston, Maine 23 March 2012 Acknowledgements I would like to thank my thesis advisors, Professor Craig Decker from the Department of German and Russian Studies and Professor Jason Thompson of the History Department, for their patience, guidance and expertise during this extensive and rewarding process. I also would also like to extend my sincere gratitude to the people who will be participating in my defense, Professor John Cole of the Bates College History Department, Profesor Raluca Cernahoschi of the Bates College German Department, and Dr. Richard Blanke from the University of Maine at Orno History Department, for their involvement during the culminating moment of my thesis experience. Finally, I would like to thank all the other people who were indirectly involved during my research process for their support. -

Read the Journal

Composite Journal 1 The following is a composite of journal made up of entries written by students in the 2008-2009 session of the Theater in London Class. The names, school years, and majors of the authors follow each entry. In some cases multiple entries for a single play are provided so as to allow the reader to see how different students responded to the same performance. Cinderella (2008). Dir. Melly Still. Based on Brothers Grimm Aschenputtel. Written by Ben Power and Melly Still. Lyric Hammersmith Theatre The Lyric Hammersmith Theatre has a reputation for unique and alternative Christmas shows, and this version of Cinderella certainly didn't disappoint. The play not only models itself after the original Grimm Brother's Aschenputtel but also incorporates elements of other traditional folk tales to add depth to the backgrounds of the characters. It is a darker and more introspective Cinderella than the Perrault-based Disney version many are familiar with, but it is by no means less tender. The depth of character development and psychological intricacy of this production are, in my opinion, its greatest strengths; though at times I felt the storytelling could have been less convoluted. I admired the Pulp-Fiction-esque timeline and its contribution to the dreaming landscape of the production, but I was occasionally distracted from the performance while trying to sort through the multiple myths and multiple timelines in my head. Another thing I admired about this production was the characterization of the step-sisters: they are not exactly sympathetic but are portrayed in a less harsh light than in most Cinderella tales I have read. -

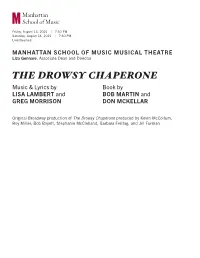

THE DROWSY CHAPERONE Music & Lyrics by Book by LISA LAMBERT and BOB MARTIN and GREG MORRISON DON MCKELLAR

Friday, August 13, 2021 | 7:30 PM Saturday, August 14, 2021 | 7:30 PM Livestreamed MANHATTAN SCHOOL OF MUSIC MUSICAL THEATRE Liza Gennaro, Associate Dean and Director THE DROWSY CHAPERONE Music & Lyrics by Book by LISA LAMBERT and BOB MARTIN and GREG MORRISON DON MCKELLAR Original Broadway production of The Drowsy Chaperone produced by Kevin McCollum, Roy Miller, Bob Boyett, Stephanie McClelland, Barbara Freitag, and Jill Furman Friday, August 13, 2021 | 7:30 PM Saturday, August 14, 2021 | 7:30 PM Livestreamed MANHATTAN SCHOOL OF MUSIC MUSICAL THEATRE Liza Gennaro, Associate Dean and Director THE DROWSY CHAPERONE Music & Lyrics by Book by LISA LAMBERT and BOB MARTIN and GREG MORRISON DON MCKELLAR Original Broadway production of The Drowsy Chaperone produced by Kevin McCollum, Roy Miller, Bob Boyett, Stephanie McClelland, Barbara Freitag and Jill Furman Evan Pappas, Director Liza Gennaro, Choreographer David Loud, Music Director Dominique Fawn Hill, Costume Designer Nikiya Mathis, Wig, Hair, and Makeup Designer Kelley Shih, Lighting Designer Scott Stauffer, Sound Designer Megan P. G. Kolpin, Props Coordinator Angela F. Kiessel, Production Stage Manager Super Awesome Friends, Video Production Jim Glaub, Scott Lupi, Rebecca Prowler, Jensen Chambers, Johnny Milani The Drowsy Chaperone is presented through special arrangement with Music Theatre International (MTI). All authorized performance materials are also supplied by MTI. www.mtishows.com STREAMING IS PRESENTED BY SPECIAL ARRANGEMENT WITH MUSIC THEATRE INTERNATIONAL (MTI) NEW YORK, NY. All authorized performance materials are also supplied by MTI. www.mtishows.com WELCOME FROM LIZA GENNARO, ASSOCIATE DEAN AND DIRECTOR OF MSM MUSICAL THEATRE I’m excited to welcome you to The Drowsy Chaperone, MSM Musical Theatre’s fourth virtual musical and our third collaboration with the video production team at Super Awesome Friends—Jim Glaub, Scott Lupi and Rebecca Prowler. -

Arthur Schnitzler and Jakob Wassermann: a Struggle of German-Jewish Identities

University of Cambridge Faculty of Modern and Medieval Languages Department of German and Dutch Arthur Schnitzler and Jakob Wassermann: A Struggle of German-Jewish Identities This dissertation is submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Max Matthias Walter Haberich Clare Hall Supervisor: Dr. David Midgley St. John’s College Easter Term 2013 Declaration of Originality I declare that this dissertation is the result of my own work. This thesis includes nothing which is the outcome of work done in collaboration except where specifically indicated in the text. Signed: June 2013 Statement of Length With a total count of 77.996 words, this dissertation does not exceed the word limit as set by the Faculty of Modern and Medieval Languages, University of Cambridge. Signed: June 2013 Summary of Arthur Schnitzler and Jakob Wassermann: A Struggle of German- Jewish Identities by Max Matthias Walter Haberich The purpose of this dissertation is to contrast the differing responses to early political anti- Semitism by Arthur Schnitzler and Jakob Wassermann. By drawing on Schnitzler’s primary material, it becomes clear that he identified with certain characters in Der Weg ins Freie and Professor Bernhardi. Having established this, it is possible to trace the development of Schnitzler’s stance on the so-called ‘Jewish Question’: a concept one may term enlightened apolitical individualism. Enlightened for Schnitzler’s rejection of Jewish orthodoxy, apolitical because he always remained strongly averse to politics in general, and individualism because Schnitzler felt there was no general solution to the Jewish problem, only one for every individual. For him, this was mainly an ethical, not a political issue; and he defends his individualist position in Professor Bernhardi.