Edinburgh Research Explorer

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

THAT MAGAZINE from Citr Fm 102 OCTOBER 1990 FREE Timbre Productions Presents

THAT MAGAZINE FROM CiTR fM 102 OCTOBER 1990 FREE Timbre Productions Presents iPRESFNT I CiTR s __ September 15 show of 101.9 fM V Death Angel, Forbid den and Sanctuary at MON. OCT. 1 the New York Theatre I has been postponed for m . now. Ticket holders can > NEW YORK THEATRE I get a refund at point of j purchase locations or 639 Commercial ticket will be honoured DOORS: 7:00PM SHOW: 7:30PM at the Death/Pesti lence/Carcass show. ALL AGES SHOW and CiTR present from Nigeria Mango Recording Artists WEA Recording Artists WED. OCT. 17 DOORS 8:00PM SSSr- SHOW 9:30PM CiTR PRESENTS ENIGMA RECORDING ARTISTS 101.9 fM A a\ ak4 ad TUES. OCT. 23 COMMODORE mop nixon band BALLROOM * with quests DOORS: 8:00PM CBS RECORDING ARTISTS INDIGO FIAJJHJ, Oct. 26 Ike 0ifo&eu4K IkecxVie W\ih £U€*U (TICKETS AVAILABLE ONLY THROUGH TICKETMASTER) TICKETS AVAILABLE AT: Zulu, Black Swan, Track, Highlife, Scratch, Razzberry Records (95th & Scott), Reminiscing Records (across from The Bay at Surrey Place), and all Ticketmaster outlets or charge by phone: 280-4444 A/AROWUAK THB HUMAN SEM1B1TB (OF CTR 1019 FAA) CONTENTS m&etrrs OCTOBER • 1990 Issue #93 ORGANIZED SHINDIG '90 WITH The lowdown on that local band competition from CiTR (present) 5 DJ SOUND WAR CHAPTER ONE The lowdown on that rap competition from CiTR (past) 5 NIRVANA Tom Milne finds it atthe New York Theatre 8 SHADOWY MEN ON A SHADOWY PLANET Don Pyle picks up the phone and screams at Nardwuar 10 TRINI LOPEZ rHe A regular guy meets the tattoo of his dreams 12 FAST3ACK$ URBAN DANCE SQUAD Pete Lutwyche and an Amsterdammer DJ join at the ear 15 PANKOW iMRTBCPER/EWCE No Kunst, No Wahnsinn. -

June 26, 1995

Volume$3.00Mail Registration ($2.8061 No. plusNo. 1351 .20 GST)21-June 26, 1995 rn HO I. Y temptation Z2/Z4-8I026 BUM "temptation" IN ate, JUNE 27th FIRST SIN' "jersey girl" r"NAD1AN TOUR DATES June 24 (2 shows) - Discovery Theatre, Vancouver June 27 a 28 - St. Denis Theatre, Montreal June 30 - NAC Theatre, Ottawa July 4 - Massey Hall, Toronto PRODUCED BY CRAIG STREET RPM - Monday June 26, 1995 - 3 theUSArts ireartstrade of and andrepresentativean artsbroadcasting, andculture culture Mickey film, coalition coalition Kantorcable, representing magazine,has drawn getstobook listdander publishing companiesKantor up and hadthat soundindicated wouldover recording suffer thatKantor heunder wasindustries. USprepared trade spokespersonCanadiansanctions. KeithThe Conference for announcement theKelly, coalition, nationalof the was revealed Arts, expecteddirector actingthat ashortly. of recent as the a FrederickPublishersThe Society of Canadaof Composers, Harris (SOCAN) Authors and and The SOCANand Frederick Music project.the preview joint participation Canadian of SOCAN and works Harris in this contenthason"areGallup the theconcerned information Pollresponsibilityto choose indicated about from.highway preserving that to He ensure a and alsomajority that our pointedthere culturalthe of isgovernment Canadiansout Canadian identity that in MusiccompositionsofHarris three MusicConcert newCanadian Company at Hallcollections Toronto's on pianist presentedJune Royal 1.of Monica Canadian a Conservatory musical Gaylord preview piano of Chatman,introducedpresidentcomposers of StevenGuest by the and their SOCAN GellmanGaylord.speaker respective Foundation, and LouisThe composers,Alexina selections Applebaum, introduced Louie. Stephen were the originatethatisspite "an 64% of American the ofKelly abroad,cultural television alsodomination policies mostuncovered programs from in of place ourstatisticsscreened the media."in US; Canada indicatingin 93% Canada there of composersdesignedSeriesperformed (Explorations toThe the introduceinto previewpieces. -

Stubborn Blood • Sara Bynoe • 108Eatio • Discqrder

STUBBORN BLOOD • SARA BYNOE • 108EATIO • DISCQRDER'% RECORD STORfBAY SPECTACUW • FIVE SIMPLE STEPS TO HAKIMITAS A MUSICIAN • RUA MINX & AJA ROSE BOND Limited edition! Only 100 copies printed! 1 i UCITR it .-• K>1.9PM/C1TR.CA DISCORDERJHN MAGAZINE FROM CiTR, • LIMITED EDITION 15-MONTH CALENDARS ! VISIT DISCORDER.CA TO BUY YOURS CELEBRATES THIRTY YEARS IN PRINT. \ AVAILABLE FOR ONLY $15. ; AND SUPPORT CiTR & DISCORDER! UPCOMING SHOWS tickets oniine: enterthevault.com i . ISQILWQRK tteketweb-ca | J?? 1 Loomis, Blackguard, The Browning, Wretched instoreiScrape j 7PM DAVID NEWBERRY tickets available at door only j doors Proceeds to WISH Drop-In Centre j 6PM | plus guests 254 East Hastings Street • 604.681.8915 FIELDS OFGREENEP RELEASE PARTY $12t cdSS PAGAHFESLWITHEHSIFERUM $30* tickets onftie: tiCketweb.CS Tyr, Heidevolk, Trolffest, Heisott In store: Scrape tickets onfine: fiveatrickshaw.com GODSOFTHEGRMIteeOAIWHORE s2Q northemtJckets.com in store: doors | TYRANTS BLOOD, EROSION, NYLITHIA and more Scrape, Neptoon, Bully's 7PM MAY HIGHLIGHTS MAY1 KILLING JOKE with Czars CASUALTIES $20+S/Cadv, DOORS 6PM Dayglo Abortions m H23 $ MAY 4 SINNED Zukuss, Excruciating Pain, Entity PICKWICK 14: $9+S/Cadv. DOORS 8:30PM $ 0IR15 ROCK CAMP FEAT. BEND SINISTER 12^ in store: Scrape, Neptoon, Bully's doors MAY 5 KVELETRAK BURNING GHATS, plus guests Gastown Tattoo, Red Cat, Zulu 8PM ___ $16.50+S/C adv. DOORS 8PM M Anchoress, Vicious Cycles & Mete Pills i *|§ fm tickets online: irveatrickshaw.com MAY 10 APOLLO GHOSTS FINAL SHOW LA CHINOA (ALBUM RELEASE) *»3S ticketweb.ca In store: doors m NO SINNER, THREE WOLF MOON & KARMA WHITE $J2 door Scrape, Millennium, Neptoon 8PM plus guests $8+S/Cadv. -

Download Report

YEARS OF IMPACT 2018/19 ANNUAL REPORT YEARS OF IMPACT 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Our Vision and Our Mission 3 Our Values 4 Message from the CEO & Board President 5 Welcoming Debbie Anderson Eng 6 Celebrating Legacy of CEO Ingrid Kastens 7 Service Streams and Impact 9 Reflecting on 35 years of PCRS 11 35 Years of Service Excellence 13 Remembering Jay Gold 15 Treasurer’s Report 17 Financial Highlights 18 Thank you to our Funders, Supporters, and Partners 19 Pictures Reflecting on 35 Years 21 2 OUR VISION Everyone thriving in strong healthy communities OUR MISSION Inspiring healthy and inclusive communities through leadership and collaboration 3 OUR VALUES Advocacy We advocate and collaborate with community partners for systemic change to advance social justice. Diversity & Inclusion We aspire to create an environment that fosters a sense of belonging, dignity, and respect. Empowerment We empower the people we serve, the communities we serve, and each other. Service Excellence We provide high-quality, people-centred services through creativity, collaboration, and growth. Stewardship We ensure financial and environmental sustainability through sound policy and innovative practices. Well-being We support the health, growth, and well-being of the people we serve, each other, and our families. 4 Message from the CEO and Board President: Looking back and looking forward at PCRS It is a particularly inspiring time at PCRS. Over the PCRS is proud to foster a work environment that past year, PCRS has made great strides toward is welcoming and respectful of everyone. We are realizing our strategic vision and outcomes while particularly elated by findings from staff surveys continuing to develop our values-driven services that reflect our commitment to diverse and inclusive in a number of key areas. -

Metal Machine Music: Technology, Noise, and Modernism in Industrial Music 1975-1996

SSStttooonnnyyy BBBrrrooooookkk UUUnnniiivvveeerrrsssiiitttyyy The official electronic file of this thesis or dissertation is maintained by the University Libraries on behalf of The Graduate School at Stony Brook University. ©©© AAAllllll RRRiiiggghhhtttsss RRReeessseeerrrvvveeeddd bbbyyy AAAuuuttthhhooorrr... Metal Machine Music: Technology, Noise, and Modernism in Industrial Music 1975-1996 A Dissertation Presented by Jason James Hanley to The Graduate School in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philsophy in Music (Music History) Stony Brook University August 2011 Copyright by Jason James Hanley 2011 Stony Brook University The Graduate School Jason James Hanley We, the dissertation committee for the above candidate for the Doctor of Philosophy degree, hereby recommend acceptance of this dissertation. Judith Lochhead – Dissertation Advisor Professor, Department of Music Peter Winkler - Chairperson of Defense Professor, Department of Music Joseph Auner Professor, Department of Music David Brackett Professor, Department of Music McGill University This dissertation is accepted by the Graduate School Lawrence Martin Dean of the Graduate School ii Abstract of the Dissertation Metal Machine Music: Technology, Noise, and Modernism in Industrial Music 1975-1996 by Jason James Hanley Doctor of Philosophy in Music (Music History) Stony Brook University 2011 The British band Throbbing Gristle first used the term Industrial in the mid-1970s to describe the intense noise of their music while simultaneously tapping into a related set of aesthetics and ideas connected to early twentieth century modernist movements including a strong sense of history and an intense self-consciousness. This model was expanded upon by musicians in England and Germany during the late-1970s who developed the popular music style called Industrial as a fusion of experimental popular music sounds, performance art theatricality, and avant-garde composition. -

Download Album Heart Barracuda Barracuda Heart Song Freeware

download album heart barracuda Barracuda Heart Song Freeware. This humorous screensaver gives us a unique look at a song bird. This cartoon bird tries very hard and puts his heart into singing but he his just not very good. File Name: songbirdsetup.exe Author: Team Taylor Made License: Freeware (Free) File Size: 1.48 Mb Runs on: Win95, Win98, WinME, WinNT 3.x, WinNT 4.x, Windows2000, WinXP, Windows2003. Feel romantic with a silky smooth burning heart on your desktop! A realistic, perfectly rendered animation of a flaming heart says 'Love' more than anything. Indulge your loved one or entertain yourself with Heart On Fire Screensaver! File Name: heart-on-fire-screensaver.ex e Author: Laconic Software License: Freeware (Free) File Size: 4.06 Mb Runs on: WinXP, WinVista, WinVista x64, Win7 x32, Win7 x64, Win2000, WinOther, Windows2000, Windows2003, WinServer, Windows Vista, Windows Tablet PC Edition 2005, Windows Media Center Edition 2005. MB Free Heart Desire Number Software is a simple and friendly software which reveals your innermost self and its manifestation. As a result, your underlying motivations for all your actions are also revealed through this number. File Name: MBFreeHeartDesireNumber.exe Author: MysticBoard.com License: Freeware (Free) File Size: 653 Kb Runs on: WinNT 4.x, Windows2000, WinXP, Windows2003, Windows Vista. MB Free Heart Desire Number Software is a simple and friendly software which reveals your innermost self and its manifestation. As a result, your underlying motivations for all your actions are also revealed through this number. File Name: MBFreeHeartDesireNumber.exe Author: MysticBoard.com License: Freeware (Free) File Size: 779 Kb Runs on: WinNT 4.x, Windows2000, WinXP, Windows2003, Windows Vista. -

Unabridged Biography

Some musings about New York City, written 2019-03-07, prompted by Eugene Barasch: I had an experience with New Yorkers in 1972 in which the artistic director of the Repertory Theatre of Lincoln Center, Jules Irving, showed me around the Vivien Beaumont Theatre so that I could suggest possible solutions to the acoustical problem they were having. When the union house that had the contract for supply and maintenance of that facility heard that I had been given this opportunity, they contacted Jules and told him that if he continued to communicate with me they would 'tar and feather and run ME out of town on a rail' and he apologized and explained that he did not know how they found out but of course he also did not initially tell me that I should not talk to anyone about what we were doing. The reason that house found out was because I called them for a quote for equipment to do the job I was recommending and explained to them that I had reviewed the situation and rather than cooperating or being interested in what I had to offer, they told Jules that they would blackball the Theatre if they continued to involve me at all. Ironically, several decades later, another consultant was brought in and recommended a very similar system which ended up being successfully installed. Because of this experience I decided not to move to New York City, which was a potential career move open to me at that time. In 1987 the first computerized theatre sound system ever (ours), which was being used at the Old Globe Theatre in San Diego to run Sondheim's 'Into the Woods' was so successful that Steve and the entire crew referred to it generically as 'The Richmond System'. -

September 1991

SEPTEMBER 1991 /•*> "...she appeared in a skimpy black skirt brandishing a whip. She toned down her dress later to try to escape the lunatic ^e#" The Province. 1991. to be continued. HOTTEST TOP 40 c STARTS A DANCE CLUB U o G U s THROW A V T PARTY, 1991 FUNDRAISER, OR CORPORATE PARTY, ITSFREE E CALL US. LA ORIGINAL R IDEAS HAPPEN AT IF YOU MISSED TOE CHANCE TO ENJOY ^ FREE COVER, CALL US FOR A FREE PASS. d DON'T MISS OUT THIS TIME 876 315 BROADWAY at KINGSWAY v70©3, OPEN s 8 PM TO 2 AM - TUE. to SAT. SUNDAYS to MIDNIGHT COWSHEAD CHRONICLES byGTH MX FATHER \MJ 1 1 SID IO XIXKE CHOI OLATF SUCK DiSfcOBPEK FRI >M SCR VI 111 I SIM; COCOA. fca^fc: BLAH...RENT,' Mil K.omi kSIR wm INGRE DIENTS \M) \ SIOU, ||()| Ilk IIIXN mi in its oi in II . n SI I.MS NOW III \l Wl REPEAT- ID mis si NDXX NIGIII IR xm mmxak BLAH...TUITDN, HON Ol UN HI 1 I'M AIR XII) AUGUST 1991 - ISSUE #104... ni vi n XSKEDNOW IOKEPLI- i \n i ins si IXHNGLX SIMPLE RECIPI IDHXVEIOPHONETHE Hit; lil X FOR SOXH MIT1 HY BOOKS, BLAH... Sill' INSIkU IIONS. 1 IIXVE. IRREGULARS HOWEVER. NO WISDOM kE- i; XKDINI; x vol M; VIAVS kin s oi PXSSXGF \ND THE WOMEN OF THE FOLK FEST XlXMNIi Ol CHOCOLATE su ci: HI 1 SOMI.ruiNi; IN Ilkl.l.X Dill 1 KIM Ill\l IS1 P- DOING DRUGS IN PUBLIC POSE DOI s | IGl kl IN MY IV The How To (or not how to) 10 mi k XNDOIIII RSTIIXISIIXLL FOR till ll\ll HI INC Will RE- HELP!!! M \IN NXM1 I I.SSBl 1 I'M si KI; Back Alley Fiction 11 1111 \l.l. -

Masthead Feature

Inside! Mags U Brochure Letter from Sheila Copps 5 Charlie Angus, editor, MP 21 QA& Saltscapes Co-publisher TALLY Linda Gourlay 2004 Magazine industry Along with many other industry representatives, grows to Q you made the trek to Ottawa last month to exchange views with lofty heights our policy makers. What are your top three concerns? Our concerns are fairly with a 23% universal among all region- A al publishers: (i) an enabling increase in environment without govern- ments ‘selling advertising’ in start-ups government-owned/competi- tively published products; agazine launches: up. Run-of-press continues on page 22 ➤ advertising pages: up. No, this isn’t a fairy tale. Canada’s magazine industry is enjoying a growth spurt. Although we had a dismal start to the millenni- Mum, with start-up numbers dwindling from record highs in the late ’90s, many publishers, old and new, laid seed to produce an impressive amount of new magazines last year. And that’s not the only good news; closures declined to a record low of 27. continues on page 10 ➤ CONTENTS March 2005 $6.95 Editor’s note 3 Reporter 4 Inside 7 Feature 10 Starts, Stops & Changes 16 People in Print 21 www.mastheadonline.com Refrigerator journalism 15 The return of Claude J. Charron 4 Bennet on the CMF 26 COVER STORY 2004 TALLY AT A GLANCE STARTS Total launches 124 CONSUMER • Niagara (Lifestyle/Calgary/CanWest Global ART/LITERARY (Regional lifestyle/St.Catharines, Communications Corp.) Total closures 27 • Beyond Arts Ont./Osprey Media Group) • Warrior Missing in action 3 (Calgary/Small -

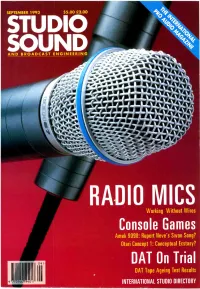

RADIO MICS Working Without Wires Console Games Amek 9098: Rupert Neve's Swan Song? Otari Concept 1: Conceptual Ecstasy?

SEPTEMBER 1993 $5.00 £2.00 STUDI SOUAND BROADCAST ENGINEERING RADIO MICS Working Without Wires Console Games Amek 9098: Rupert Neve's Swan Song? Otari Concept 1: Conceptual Ecstasy? DAT On Trial DAT Tape Ageing Test Results 9 770144 594017 INTERNATIONAL STUDIO DIRECTORY G PLUS CONSOLE SYSTEMS 3.5" disk drives allow the use of low cost, high capacity disks for mix data storage Audio phase scope provides permanent display of amplitude and phase relation- ship of left and right stereo signals Wireless talkback system uses a PCM encoded infra -red handset G Plus consoles additionally provide: REDESIGNED GROUP AND MAIN BUFFERED MAIN OUTPUT 3.51N DISK DRIVES MIX AMPS DISTRIBUTION AUDIO PHASE SCOPE PAIR OF PPM METERS SECOND MINI SPEAKER OUTPUT WIRELESS TALKBACK SYSTEM PUSH/PUSH SWITCHING TO MUTE GROUP CROSS-NORMALLING AUTOMATED SOLO AUX MASTERS BLACK TRIM STRIPS VIDEO SWITCHER LISTEN MIC POST -COMPRESSOR On consoles of 72 channels or over: G SERIES OR E SERIES EQUALISERS OUTFUT TO PATCHBAY A FULLY-CONNECTORISED REMOTE SSL's OWN LINEAR CRYSTAL- CUE STEREO 1ORMALLING PATCHBAY BECOMES A NON - OXYGEN -FREE CABLE LED METER ILLUMINATION CHARGEABLE OPTION Solid State Logic Intentional Headquarter: Begbrol.e, Oxford, England OX5 1RU Tel: (0865) 842300 Paris (1) 34 60 4666 Darmstadt (6150 938640 Milan (2 262 249% Tokyo (3) 54 74 11 44 New York (212) 3151111 Los Angelas (213) 463 4444 STUDIO SOUND AND BROADCAST ENGINEERING Postpro the French way. See page 45 5 Editorial 20 Music News 49 Digital Audio Falling equipment prices may kocktron s Chameleon guitar not be the good news many preamp-effects unit finds Interchange would have us believe. -

VERDICT Nekrophile Presents Muzak for the Happy

d -m• t v. IPieirt 5ropA+:.. > ;ClJ I « 7 1IIO I ON DENMAN 1AN<&'$- A SOPT truLTWRSp arnN*<5 ATMc>5fweKr IN T«e W©M2*T©F EN$U$M gAY I UOPENM AN sr. IF ^0U UKK* TMC MdAnVfcWEEV aPT, rrpoes^'r MEAN v&a'u-UKC "fon$o's>. pur #I/E IT AiKy.., #>$p pespcE... 5<2PT ATMOSPHERE... "TA*<o? DiSfcOBDER That Magazine from CITR fml02 cablelOO October 1986 • Vol. 4/No. 9 EDITOR Bill Mullan WRITERS Don Chow, Julia Steele, Larry Thiessen, Mark Mushet, Iain Bowman, Travis B„ Robert Shea, Kevin Smith, Jerome Broadway, Bill Mullan ART DIRECTOR Eric Damianos CARTOONS William Thompson, Pat Mullan, Rod Filbrandt,Susan Catherine COVER Illustration — William Thompson Colour — David Wilson, William Thompson IN THIS ISSUE PRODUCTION MANAGER HORROR Karen Shea Remember how much fun it was the last time you were really DESIGN scared. Bill Mullan does. 7 Harreson Atley LAYOUT TAKIN' THE RAP Pat Carroll, Robin Razzell Lynn Snedden What do Fats Comet, Tackhead, Marc Stewart & the Mafia, and Mike Mines, Shedo Ollek, Eric Damianos, ABC have in common? More than you'd think. A chilling Johanna Block, Randy Iwata, Karen Shea psychodrama, directed by Don Chow. 12 TYPESETTING Sheila Haldane, Lisa Cameron SHINDIG Some good things can't help but get better. 16 BUSINESS MANAGER Randy Iwata ADVERTISING MANAGER IN EVERY ISSUE Robin Razzell DISTRIBUTION MANAGER Bill Mullan AIRHEAD SUBSCRIPTIONS MANAGER Correspondence from our readers, the geniuses who actually Randy Iwata run western civilization. 4 PUBLISHER BEHIND THE DIAL Harry Hertscheg The true meaning of life, recruitment for the Foreign Legion and yet another sparkling new face. -

May 2018 New Releases

May 2018 New Releases what’s inside featured exclusives PAGE 3 RUSH Releases Vinyl Available Immediately! 76 Vinyl Audio 3 CD Audio 17 LORDS OF ACID - DALE HAWKINS - MISSION UK - FEATURED RELEASES PRETTY IN KINK L.A., MEMPHIS AND LIVE AT ROCKPALAST (LIMITED EDITION VINYL) TYLER, TEXAS (2 CD + DVD) Music Video DVD & Blu-ray 50 Non-Music Video DVD & Blu-ray 54 Order Form 86 Deletions and Price Changes 83 800.888.0486 THE LAST HOUSE ON SAVANNAH SMILES BLACK VENUS 203 Windsor Rd., Pottstown, PA 19464 THE LEFT (COLLECTOR’S EDITION) LORDS OF ACID - AMYL AND THE SNIFFERS - BLEEDING THROUGH - www.MVDb2b.com [LIMITED EDITION] [BLU-RAY + DVD] PRETTY IN KINK BIG ATTRACTION & GIDDY UP PORTRAIT OF THE GODDESS (LIMITED EDITION VINYL) MVD In May - A Real Mutha For Ya! A Mother month from your sons and daughters at MVD! Kick off your heels and get down with the sultry sounds and raw electro- carnality of LORDS OF ACID, as they bear their latest CD and LP PRETTY IN KINK. Sure to be an electro-industrial-techno classic! DANA FUCHS, a blues singer whose “voice is dirty and illicit, evoking Joplin, Jagger and a cigarette butt bobbing in a glass of bourbon,” births her latest CD LOVE LIVES ON. On her seventh disc, Fuchs searches for hope and redemption in her soul-drenched delivery and “Triumphal” presentation. Fuchs also starred in the film ACROSS THE UNIVERSE, playing a “blues singer, very hip chick and Earth Mother.” Love Lives On in these grooves! PATTY SMYTH AND SCANDAL CD. 80s classics done live by the artist who had the bestselling EP in Columbia Records history! Patty was offered to be the lead singer in Van Halen but turned it down as she was 8 months pregnant.