The Enduring Importance of Family Wealth: Evidence from the Forbes 400, 1982 to 2013

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Compendium of Federal Estate Tax and Personal W Ealth Studies

A Comparison of Wealth Estimates for America’s Wealthiest Decedents Using Tax Data and Data from the Forbes 400 Brian Raub, Barry Johnson, and Joseph Newcomb, Statistics of Income, IRS1 Presented in “New Research on Wealth and Estate Taxation” Introduction Measuring the wealth of the Nation’s citizens has long been a topic of interest among researchers and policy planners. Unfortunately, such measurements are difficult to make because there are few sources of data on the wealth holdings of the general population, and most especially of the very rich. Two of the better-known sources of wealth statistics are the household estimates derived from the Federal Reserve Board of Governor’s Survey of Consumer Finances (SCF) (Kenneckell, 2009) and estimates of personal wealth derived from estate tax Chapter 7 — Studies Linking Income & Wealth returns, produced by the Statistics of Income Division (SOI) of the Internal Revenue Service (Raub, 2007). In addition, Forbes magazine annually has produced a list, known as the Forbes 400, that includes wealth estimates for the 400 wealthiest individuals in the U.S. While those included on the annual Forbes 400 list represent less than .0002 percent of the U.S. population, this group holds a relatively large share of the Nation’s wealth. For example, in 2007, the almost $1.6 trillion in estimated collective net worth owned by the Forbes 400 accounted for about 2.3 percent of total U.S. household net worth (Kopczuk and Saez, 2004). This article focuses on the estimates of wealth produced for the Forbes 400 and their relationship to data collected by SOI (see McCubbin, 1994, for results of an earlier pilot of this study). -

Warren Wealth Tax Would Have Raised $114 Billion in 2020 from Nation’S 650 Billionaires Alone

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE: MARCH 1, 2021 WARREN WEALTH TAX WOULD HAVE RAISED $114 BILLION IN 2020 FROM NATION’S 650 BILLIONAIRES ALONE Ten-Year Revenue Total Would Be $1.4 Trillion Even as Billionaire Wealth Continued to Grow WASHINGTON, D.C. – America’s billionaires would owe a total of about $114 billion in wealth tax for 2020 if the Ultra-Millionaire Tax Act introduced today by Sen. Elizabeth Warren (D-MA), Rep. Pramila Jayapal (D-WA) and Rep. Brendan Boyle (D-PA) had been in effect last year, based on Forbes billionaire wealth data analyzed by Americans for Tax Fairness (ATF) and the Institute for Policy Studies Project on Inequality (IPS). The ten-year revenue total would be about $1.4 trillion, and yet U.S. billionaire wealth would continue to grow. (The 10-year revenue estimate is explained below.) Billionaire wealth is top-heavy, so just the richest 15 own one-third of all the wealth and would thus be liable for about a third of the wealth tax (see table below). Under the Ultra-Millionaire Tax Act, those 15 richest billionaires would have paid a total of $40 billion in wealth tax for the 2020 tax year, but their projected collective wealth would have still increased by more than half (53%), only slightly lower than their actual 58% increase in wealth without the wealth tax, since March 18, 2020, the rough beginning of the pandemic and the start date for this analysis. Full billionaire data is here. Some examples from the top of the list: Jeff Bezos would pay $5.7 billion in wealth taxes for 2020, lowering the size of his fortune from $191.2 billion to $185.5 billion, or 5%, but it still would have increased by two-thirds from March 18 to the end of the year. -

This Year's Edition

CO-AUTHORS: Chuck Collins directs the Program on Inequality and the Common Good at the Institute for Policy Studies, where he also co-edits Inequality.org. His most recent book is Is Inequality in America Irreversible? from Polity Press and in 2016 he published Born on Third Base. Other reports and books by Collins include Reversing Inequality: Unleashing the Transformative Potential of An More Equal Economy and 99 to 1: How Wealth Inequality is Wrecking the World and What We Can Do About It. His 2004 book Wealth and Our Commonwealth, written with Bill Gates Sr., makes the case for taxing inherited fortunes. Josh Hoxie directs the Project on Opportunity and Taxation at the Institute for Policy Studies and co- edits Inequality.org. He co-authored a number of reports on topics ranging from economic inequality, to the racial wealth divide, to philanthropy. Hoxie has written widely on income and wealth maldistribution for Inequality.org and other media outlets. He worked previously as a legislative aide for U.S. Senator Bernie Sanders. Acknowledgements: We received significant assistance in the production of this report. We would like to thank our colleagues at IPS who helped us throughout the report. The Institute for Policy Studies (www.IPS-dc.org) is a multi-issue research center founded in 1963. The Program on Inequality and the Common Good was founded in 2006 to draw attention to the growing dangers of concentrated wealth and power, and to advocate policies and practices to reverse extreme inequalities in income, wealth, and opportunity. The Inequality.org website (http://inequality.org/) provides an online portal into all things related to the income and wealth gaps that so divide us. -

Billionaire Bonanza 2017: the Forbes 400 and the Rest of Us

CO-AUTHORS: Chuck Collins directs the Program on Inequality and the Common Good at the Institute for Policy Studies, where he also co-edits Inequality.org. His most recent book: Born on Third Base: A One Percenter Makes the Case for Tackling Inequality, Bringing Wealth Home, and Committing to the Common Good. Other reports and books by Collins include Reversing Inequality: Unleashing the Transformative Potential of An More Equal Economy and 99 to 1: How Wealth Inequality is Wrecking the World and What We Can Do About It. His 2004 book Wealth and Our Commonwealth, written with Bill Gates Sr., makes the case for taxing inherited fortunes, and his The Moral Measure of the Economy, written with Mary Wright, explores Christian ethics and economic life. Collins co-founded the Patriotic Millionaires and United for a Fair Economy. Josh Hoxie directs the Project on Opportunity and Taxation at the Institute for Policy Studies and co- edits Inequality.org. He co-authored a number of reports on topics ranging from economic inequality, to the racial wealth divide, to philanthropy. Hoxie has written widely on income and wealth maldistribution for Inequality.org and other media outlets. He worked previously as a legislative aide for U.S. Senator Bernie Sanders. Graphic Design: Kenneth Worles, Jr. Data Analyst: Amanda Page-Hoongrajok, University of Massachusetts Amherst. Acknowledgements: We received significant assistance in the production of this report. We would like to thank our colleagues at IPS who helped us throughout the report development process, especially Jessicah Pierre, Sam Pizzigati, and Sarah Anderson. The Institute for Policy Studies (www.IPS-dc.org) is a multi-issue research center that has been conducting path-breaking research on inequality for more than 20 years. -

Wealth, Power and the Future of the Planet: Four Arguments Against the Extreme Concentration of Wealth

— WEALTH, POWER, AND THE FUTURE OF THE PLANET — WEALTH, POWER AND THE FUTURE OF THE PLANET: FOUR ARGUMENTS AGAINST THE EXTREME CONCENTRATION OF WEALTH JACK SANTA BARBARA, PH. D SUMMARY Contrary to popular beliefs, extremes in wealth are bad for society, the economy, and the planet. Concentration of wealth is unjust and confers undue advantage to those with the most wealth, who then use this wealth primarily to usurp the democratic process and further enrich themselves at the expense of the majority, and the ecosystems that support all life. There is no moral or economic justification for extremes in wealth. Wealth accumulation is often accomplished by illegal means, but it can also derive from the unjust (but legal) pressure that the wealthy use to influence lawmakers to legislate in their favor. The accumulation of extreme wealth1 is the result of laws that inappropriately reward the marginal contributions of individual innovation but ignore the vastly larger contributions that flow from the heritage of common knowledge. This extreme wealth, which has gone into private hands, truly belongs in the public purse. The very wealthy “didn’t earn it and don’t deserve it.” Reducing the extremes in wealth is therefore a major goal for progressives of all kinds. - 111 - — WEALTH, POWER, AND THE FUTURE OF THE PLANET — HOW MUCH IS A BILLION DOLLARS? As of 2011, there were well over one thousand billionaires on the planet. Consider for a moment what $1 billion represents. If you were to count out one dollar a second on a 24/7 basis, it would take you about 12 days to reach one million dollars. -

Current Affairs Capsule for SBI/IBPS/RRB PO Mains Exam 2021 – Part 2

Current Affairs Capsule for SBI/IBPS/RRB PO Mains Exam 2021 – Part 2 Important Awards and Honours Winner Prize Awarded By/Theme/Purpose Hyderabad International CII - GBC 'National Energy Carbon Neutral Airport having Level Airport Leader' and 'Excellent Energy 3 + "Neutrality" Accreditation from Efficient Unit' award Airports Council International Roohi Sultana National Teachers Award ‘Play way method’ to teach her 2020 students Air Force Sports Control Rashtriya Khel Protsahan Air Marshal MSG Menon received Board Puruskar 2020 the award NTPC Vallur from Tamil Nadu AIMA Chanakya (Business Simulation Game)National Management Games(NMG)2020 IIT Madras-incubated Agnikul TiE50 award Cosmos Manmohan Singh Indira Gandhi Peace Prize On British broadcaster David Attenborough Chaitanya Tamhane’s The Best Screenplay award at Earlier, it was honoured with the Disciple Venice International Film International Critics’ Prize awarded Festival by FIPRESCI. Chloe Zhao’s Nomadland Golden Lion award at Venice International Film Festival Aditya Puri (MD, HDFC Bank) Lifetime Achievement Award Euromoney Awards of Excellence 2020. Margaret Atwood (Canadian Dayton Literary Peace Prize’s writer) lifetime achievement award 2020 Click Here for High Quality Mock Test Series for IBPS RRB PO Mains 2020 Click Here for High Quality Mock Test Series for IBPS RRB Clerk Mains 2020 Follow us: Telegram , Facebook , Twitter , Instagram 1 Current Affairs Capsule for SBI/IBPS/RRB PO Mains Exam 2021 – Part 2 Rome's Fiumicino Airport First airport in the world to Skytrax (Leonardo -

Silver Spoon Oligarchs

CO-AUTHORS Chuck Collins is director of the Program on Inequality and the Common Good at the Institute for Policy Studies where he coedits Inequality.org. He is author of the new book The Wealth Hoarders: How Billionaires Pay Millions to Hide Trillions. Joe Fitzgerald is a research associate with the IPS Program on Inequality and the Common Good. Helen Flannery is director of research for the IPS Charity Reform Initiative, a project of the IPS Program on Inequality. She is co-author of a number of IPS reports including Gilded Giving 2020. Omar Ocampo is researcher at the IPS Program on Inequality and the Common Good and co-author of a number of reports, including Billionaire Bonanza 2020. Sophia Paslaski is a researcher and communications specialist at the IPS Program on Inequality and the Common Good. Kalena Thomhave is a researcher with the Program on Inequality and the Common Good at the Institute for Policy Studies. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The authors wish to thank Sarah Gertler for her cover design and graphics. Thanks to the Forbes Wealth Research Team, led by Kerry Dolan, for their foundational wealth research. And thanks to Jason Cluggish for using his programming skills to help us retrieve private foundation tax data from the IRS. THE INSTITUTE FOR POLICY STUDIES The Institute for Policy Studies (www.ips-dc.org) is a multi-issue research center that has been conducting path-breaking research on inequality for more than 20 years. The IPS Program on Inequality and the Common Good was founded in 2006 to draw attention to the growing dangers of concentrated wealth and power, and to advocate policies and practices to reverse extreme inequalities in income, wealth, and opportunity. -

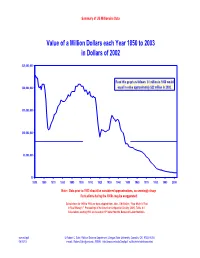

Summary of Millionaire Materials

Summary of US Millionaire Data Value of a Million Dollars each Year 1850 to 2003 in Dollars of 2002 $25,000,000 Read this graph as follows: $1 million in 1850 would $20,000,000 equal in value approximately $22 million in 2002. $15,000,000 $10,000,000 $5,000,000 $0 1850 1860 1870 1880 1890 1900 1910 1920 1930 1940 1950 1960 1970 1980 1990 2000 Note: Data prior to 1913 should be considered approximations, so seemingly sharp fluctuations during the 1800s may be exaggerated. Calculations for 1850 to 1912 use data adapted from John J. McCusker, "How Much Is That in Real Money?," Proceedings of the American Antiquarian Society (2001), Table A-1. Calculations starting 1913 are based on CPI data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics. summill.pdf © Robert C. Sahr, Political Science Department, Oregon State University, Corvallis, OR 97331-6206 06/10/03 e-mail: [email protected]; WWW: http://www.orst.edu/Dept/pol_sci/fac/sahr/sahrhome.html Summary of US Millionaire Data, page 2 Dollars Needed to Equal in Value $1 Million in the Year 2002 for each Year 1850 to 2003 $1,100,000 $1,000,000 $900,000 $800,000 $700,000 Read this graph as follows: To equal the $600,000 value of $1 million in dollars of the year 2002 would have required about $45,000 in 1850. $500,000 $400,000 $300,000 $200,000 $100,000 $0 1850 1860 1870 1880 1890 1900 1910 1920 1930 1940 1950 1960 1970 1980 1990 2000 Note: Data prior to 1913 should be considered approximations, so seemingly sharp fluctuations during the 1800s may be exaggerated. -

The Forbes 400 and the Gates-Buffett Giving Pledge

ACRN Journal of Finance and Risk Perspectives Vol. 4, Issue 1, February 2015, p. 82-101 ISSN 2305-7394 THE FORBES 400 AND THE GATES-BUFFETT GIVING PLEDGE 1 2 4 Kent Hickman , Mark Shrader , Danielle Xu3, Dan Lawson 1,2,3 School of Business Administration, Gonzaga University 4Department of Finance, Indiana University of Pennsylvania Abstract. Large disparities in the distribution of wealth across the world’s population may contribute to political and societal instability. While public policy decisions regarding taxes and transfer payments could lead to more equal wealth distribution, they are controversial. This paper examines a voluntary initiative aimed at wealth redistribution, the Giving Pledge, developed by Warren Buffet and Bill and Melinda Gates. High wealth individuals signing the pledge commit to give at least half of their wealth to charity either over their lifetime or in their will. We attempt to identify personal characteristics of America’s billionaires that influence their decision to sign the pledge. We find several factors that are related to the likelihood of giving, including the individual’s net worth, the source of their wealth, their level of education, their notoriety and their political affiliation. Keywords: Philanthropy, Giving Pledge, Forbes 400, wealth redistribution Introduction The Giving Pledge is an effort to help address society’s most pressing problems by inviting the world’s wealthiest individuals and families to commit to giving more than half of their wealth to philanthropy or charitable causes either during their lifetime or in their will. (The Giving Pledge, 2013). The extremely rich are known to purchase islands, yachts, sports teams and collect art in their pursuit of happiness. -

Uvic Thesis Template

Degrowth in Canada: Critical perspectives from the ground by Claire O’Manique Bachelor of Arts, University of Guelph, 2015 A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS in the School of Environmental Studies © Claire O’Manique, 2019 University of Victoria All rights reserved. This thesis may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by photocopy or other means, without the permission of the author. Supervisory Committee Degrowth in Canada: Critical perspectives from the ground Claire O’Manique Bachelor of Arts, University of Guelph, 2015 Supervisory Committee Dr. James Rowe, Supervisor School of Environmental Studies Dr. Karena Shaw, Departmental Member School of Environmental Studies ii Abstract: Degrowth is an emerging field of research and a social movement founded on the premise that perpetual economic growth is incompatible with the biophysical limits of our finite planet (D’Alisa, Demaria & Kallis, 2014a; Asara, Otero, Demaria & Corbera, 2015). Despite the important work that degrowth scholars and activists have done to broadcast the fundamental contradiction between endless compound growth and a finite resource base, degrowth remains politically marginal, having received little mainstream attention or policy uptake. This thesis explores why. In particular, I examine barriers to and pathways towards the uptake of degrowth in Canada, a country that disproportionately contributes to climate breakdown. To do so I ask: 1) What barriers exist to advancing a degrowth agenda in Canada?; 2) How specifically do those barriers block degrowth from taking hold in contemporary Canadian policy and political discourse?; 3) How (if at all) are Canadian activists seeking to address these barriers? This research reveals that the political economy in Canada, and the way that is expressed in concentrations of elite and corporate power has given certain actors, particularly the fossil fuel industry, immense economic and political power. -

Billionaire Bonanza Reports in 2015 and 2017

CO-AUTHORS: Chuck Collins directs the Program on Inequality and the Common Good at the Institute for Policy Studies, where he also co-edits Inequality.org. His most recent book is Is Inequality in America Irreversible? from Polity Press and in 2016 he published Born on Third Base. Other reports and books by Collins include Reversing Inequality: Unleashing the Transformative Potential of An More Equal Economy and 99 to 1: How Wealth Inequality is Wrecking the World and What We Can Do About It. His 2004 book Wealth and Our Commonwealth, written with Bill Gates Sr., makes the case for taxing inherited fortunes. Josh Hoxie directs the Project on Opportunity and Taxation at the Institute for Policy Studies and co- edits Inequality.org. He co-authored a number of reports on topics ranging from economic inequality, to the racial wealth divide, to philanthropy. Hoxie has written widely on income and wealth maldistribution for Inequality.org and other media outlets. He worked previously as a legislative aide for U.S. Senator Bernie Sanders. Acknowledgements: We received significant assistance in the production of this report. We would like to thank our colleagues at IPS who helped us throughout the report. The Institute for Policy Studies (www.IPS-dc.org) is a multi-issue research center founded in 1963. The Program on Inequality and the Common Good was founded in 2006 to draw attention to the growing dangers of concentrated wealth and power, and to advocate policies and practices to reverse extreme inequalities in income, wealth, and opportunity. The Inequality.org website (http://inequality.org/) provides an online portal into all things related to the income and wealth gaps that so divide us. -

The Plutonomy of the 1%: Dominant Ownership and Conspicuous Consumption in the New Gilded Age

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Di Muzio, Tim Article — Published Version The Plutonomy of the 1%: Dominant Ownership and Conspicuous Consumption in the New Gilded Age Millennium: Journal of International Studies Provided in Cooperation with: The Bichler & Nitzan Archives Suggested Citation: Di Muzio, Tim (2015) : The Plutonomy of the 1%: Dominant Ownership and Conspicuous Consumption in the New Gilded Age, Millennium: Journal of International Studies, The Bichler and Nitzan Archives, Toronto, Vol. 43, Iss. 2, pp. 492-510, http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0305829814557345 , http://bnarchives.yorku.ca/433/ This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/157792 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte. may exercise further usage rights as specified in the indicated licence.