Billionaire Bonanza 2017: the Forbes 400 and the Rest of Us

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Preview Chapter 7: a Few Good Women

7 A Few Good Women Zhou Qunfei grew up poor in Hunan Province, where she worked on her family’s farm to help support her family. Later, while working at a factory in Guangdong Province, she took business and computer courses at Shen- zhen University. She started a company with money she saved working for a watch producer. In 2015 she was the world’s richest self-made woman, with a fortune of $5.3 billion, according to Forbes. Her wealth comes from her company, Lens Technology, which makes touchscreens. It employs 60,000 people and has a market capitalization of nearly $12 billion. Lei Jufang was born in Gansu Province, one of the poorest areas of northwest China. After studying physics at Jiao Tong University, she cre- ated a new method for vacuum packaging food and drugs, which won her acclaim as an assistant professor. On a trip to Tibet she became fascinated by herbal medicines. In 1995 she founded a drug company, Cheezheng Tibetan Medicine, harnessing her skill in physics and engineering to exploit the untapped market for Tibetan medicine. Her company has a research institute and three factories that produce herbal healing products for con- sumers in China, Malaysia, Singapore, and North and South America. She has amassed a fortune of $1.5 billion. In most countries, women get rich by inheriting money. China is dif- ferent: The majority of its women billionaires are self-made. Zhou Qunfei and Lei Jufang are unusual because they established their own companies. Most of the eight Chinese female self-made company founders worth more than $1 billion made their money in real estate or in companies founded jointly with husbands or brothers. -

Compendium of Federal Estate Tax and Personal W Ealth Studies

A Comparison of Wealth Estimates for America’s Wealthiest Decedents Using Tax Data and Data from the Forbes 400 Brian Raub, Barry Johnson, and Joseph Newcomb, Statistics of Income, IRS1 Presented in “New Research on Wealth and Estate Taxation” Introduction Measuring the wealth of the Nation’s citizens has long been a topic of interest among researchers and policy planners. Unfortunately, such measurements are difficult to make because there are few sources of data on the wealth holdings of the general population, and most especially of the very rich. Two of the better-known sources of wealth statistics are the household estimates derived from the Federal Reserve Board of Governor’s Survey of Consumer Finances (SCF) (Kenneckell, 2009) and estimates of personal wealth derived from estate tax Chapter 7 — Studies Linking Income & Wealth returns, produced by the Statistics of Income Division (SOI) of the Internal Revenue Service (Raub, 2007). In addition, Forbes magazine annually has produced a list, known as the Forbes 400, that includes wealth estimates for the 400 wealthiest individuals in the U.S. While those included on the annual Forbes 400 list represent less than .0002 percent of the U.S. population, this group holds a relatively large share of the Nation’s wealth. For example, in 2007, the almost $1.6 trillion in estimated collective net worth owned by the Forbes 400 accounted for about 2.3 percent of total U.S. household net worth (Kopczuk and Saez, 2004). This article focuses on the estimates of wealth produced for the Forbes 400 and their relationship to data collected by SOI (see McCubbin, 1994, for results of an earlier pilot of this study). -

September 22, 2019 Democracies Become Oligarchies When Wealth Is

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, BERKELEY BERKELEY • DAVIS • IRVINE • LOS ANGELES • MERCED • RIVERSIDE • SAN DIEGO • SAN FRANCISCO SANTA BARBARA • SANTA CRUZ EMMANUEL SAEZ AND GABRIEL ZUCMAN PROFESSORS OF ECONOMICS 530 EVANS HALL #3880 BERKELEY CA 94720 -3880 [email protected] [email protected] September 22, 2019 Democracies become oligarchies when wealth is too concentrated. A progressive wealth tax is the most direct policy tool to curb the growing concentration of wealth in the United States. It can also restore tax progressivity at the very top of the wealth distribution and raise sorely needed tax revenue to fund the public good. Senator Sanders' very progressive wealth tax on the top 0.1% wealthiest Americans is a crucial step in this direction. We estimate that Sanders’ wealth tax would raise $4.35 trillion over a decade and fully eliminate the gap between wealth growth for billionaires and wealth growth for the middle class. Combining progressive wealth taxation with policies to rebuild middle class wealth is what the United States needs to ensure vibrant and equitable growth for the future. We have analyzed Senator Sanders’ proposal to impose a progressive annual wealth tax on American households with net worth (sum of all assets net of debts) above $32 million. The tax rate would start at 1% of net worth from $32 to $50 million, increase to 2% on net worth from $50 to $250 million, 3% from $250 to $500 million, 4% from $500 million to $1 billion, 5% from $1 to $2.5 billion, 6% from $2.5 to $5 billion, 7% from $5 to $10 billion, and 8% on wealth over $10 billion (the brackets apply for married taxpayers and are halved for singles). -

Warren Wealth Tax Would Have Raised $114 Billion in 2020 from Nation’S 650 Billionaires Alone

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE: MARCH 1, 2021 WARREN WEALTH TAX WOULD HAVE RAISED $114 BILLION IN 2020 FROM NATION’S 650 BILLIONAIRES ALONE Ten-Year Revenue Total Would Be $1.4 Trillion Even as Billionaire Wealth Continued to Grow WASHINGTON, D.C. – America’s billionaires would owe a total of about $114 billion in wealth tax for 2020 if the Ultra-Millionaire Tax Act introduced today by Sen. Elizabeth Warren (D-MA), Rep. Pramila Jayapal (D-WA) and Rep. Brendan Boyle (D-PA) had been in effect last year, based on Forbes billionaire wealth data analyzed by Americans for Tax Fairness (ATF) and the Institute for Policy Studies Project on Inequality (IPS). The ten-year revenue total would be about $1.4 trillion, and yet U.S. billionaire wealth would continue to grow. (The 10-year revenue estimate is explained below.) Billionaire wealth is top-heavy, so just the richest 15 own one-third of all the wealth and would thus be liable for about a third of the wealth tax (see table below). Under the Ultra-Millionaire Tax Act, those 15 richest billionaires would have paid a total of $40 billion in wealth tax for the 2020 tax year, but their projected collective wealth would have still increased by more than half (53%), only slightly lower than their actual 58% increase in wealth without the wealth tax, since March 18, 2020, the rough beginning of the pandemic and the start date for this analysis. Full billionaire data is here. Some examples from the top of the list: Jeff Bezos would pay $5.7 billion in wealth taxes for 2020, lowering the size of his fortune from $191.2 billion to $185.5 billion, or 5%, but it still would have increased by two-thirds from March 18 to the end of the year. -

Explaining Variations in the Billionaire-Intensity of GDP

Picture credit: khunaspix/Bigstock.com Expert Comment Why do some countries have more billionaires than others? Explaining variations in the billionaire-intensity of GDP Copyright © 2018 by Dialogue of Civilizations Research Institute The right of Vladimir Popov to be identified as the author of this publication is hereby asserted. The views and opinions expressed in this publication are those of the original author(s) and do not necessarily represent or reflect the views and opinions of the Dialogue of Civilizations Research Institute, its co-founders, or its staff members. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, distributed, or transmitted in any form or by any means, including photocopying, recording, or other electronic or mechanical methods, without the prior written permission of the publisher, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical reviews and certain other noncommercial uses permitted by copyright law. For permission requests, please write to the publisher: Dialogue of Civilizations Research Institute gGmbH Französische Straße 23 10117 Berlin Germany +49 30 209677900 [email protected] 1 Dialogue of Civilizations Research Institute Why some countries have more billionaires than others? Explaining variations in the billionaire-intensity of GDP Vladimir Popov The Forbes magazine annual list of billionaires and their wealth provides enough data so that the number of billionaires per unit of GDP and the ratio of their wealth-to-GDP can be calculated for various countries. These measures of billionaire intensity vary greatly – sometimes by one or even two orders of magnitude. This paper offers descriptive statistics of the geographical distribution of billionaires and a preliminary analysis of factors that determine the country variations of billionaire intensity indicators. -

BILLIONAIRE PANDEMIC WEALTH GAINS of 55%, OR $1.6 TRILLION, COME AMID THREE DECADES of RAPID WEALTH GROWTH April 15, 2021

BILLIONAIRE PANDEMIC WEALTH GAINS OF 55%, OR $1.6 TRILLION, COME AMID THREE DECADES OF RAPID WEALTH GROWTH April 15, 2021 Whether measured over 13 months or 31 years, the growth of U.S. billionaire wealth is both astounding and troubling based on Forbes data as of April 12, 2021. Billionaire wealth growth has perversely accelerated over the 13 months of global pandemic. But the piling up of fortunes at the top has proceeded at a rapid clip for decades even as the net worth of working Americans lagged and public services deteriorated. Tax reforms of the type proposed by President Biden would begin to reverse these damaging trends. GROWTH OF BILLIONAIRE WEALTH DURING THE FIRST-THREE MONTHS OF THE PANDEMIC Between March 18, 2020, and April 12, 2021,the collective wealth of American billionaires leapt by $1.62 trillion, or 55%, from $2.95 trillion to $4.56 trillion. [See data table here]. That increase in billionaire wealth alone could pay for nearly 70% of the 10-year, $2.3 trillion cost of President Biden’s proposed jobs and infrastructure plan—the American Jobs Plan. As of April 12, there were six American “centi-billionaires”—individuals each worth at least $100 billion [see table below]. That’s bigger than the size of the economy of each of 13 of the nation’s states. Here’s how the wealth of these ultra-billionaires grew during the pandemic: ● Amazon’s Jeff Bezos, almost a “double-centi-billionaire” with a net worth of nearly $197 billion, is up 74% over the last 13 months. -

Media Oligarchs Go Shopping Patrick Drahi Groupe Altice

MEDIA OLIGARCHS GO SHOPPING Patrick Drahi Groupe Altice Jeff Bezos Vincent Bolloré Amazon Groupe Bolloré Delian Peevski Bulgartabak FREEDOM OF THE PRESS WORLDWIDE IN 2016 AND MAJOR OLIGARCHS 2 Ferit Sahenk Dogus group Yildirim Demirören Jack Ma Milliyet Alibaba group Naguib Sawiris Konstantin Malofeïev Li Yanhong Orascom Marshall capital Baidu Anil et Mukesh Ambani Rupert Murdoch Reliance industries ltd Newscorp 3 Summary 7. Money’s invisible prisons 10. The hidden side of the oligarchs New media empires are emerging in Turkey, China, Russia and India, often with the blessing of the political authorities. Their owners exercise strict control over news and opinion, putting them in the service of their governments. 16. Oligarchs who came in from the cold During Russian capitalism’s crazy initial years, a select few were able to take advantage of privatization, including the privatization of news media. But only media empires that are completely loyal to the Kremlin have been able to survive since Vladimir Putin took over. 22. Can a politician be a regular media owner? In public life, how can you be both an actor and an objective observer at the same time? Obviously you cannot, not without conflicts of interest. Nonetheless, politicians who are also media owners are to be found eve- rywhere, even in leading western democracies such as Canada, Brazil and in Europe. And they seem to think that these conflicts of interests are not a problem. 28. The royal whim In the Arab world and India, royal families and industrial dynasties have created or acquired enormous media empires with the sole aim of magnifying their glory and prestige. -

This Year's Edition

CO-AUTHORS: Chuck Collins directs the Program on Inequality and the Common Good at the Institute for Policy Studies, where he also co-edits Inequality.org. His most recent book is Is Inequality in America Irreversible? from Polity Press and in 2016 he published Born on Third Base. Other reports and books by Collins include Reversing Inequality: Unleashing the Transformative Potential of An More Equal Economy and 99 to 1: How Wealth Inequality is Wrecking the World and What We Can Do About It. His 2004 book Wealth and Our Commonwealth, written with Bill Gates Sr., makes the case for taxing inherited fortunes. Josh Hoxie directs the Project on Opportunity and Taxation at the Institute for Policy Studies and co- edits Inequality.org. He co-authored a number of reports on topics ranging from economic inequality, to the racial wealth divide, to philanthropy. Hoxie has written widely on income and wealth maldistribution for Inequality.org and other media outlets. He worked previously as a legislative aide for U.S. Senator Bernie Sanders. Acknowledgements: We received significant assistance in the production of this report. We would like to thank our colleagues at IPS who helped us throughout the report. The Institute for Policy Studies (www.IPS-dc.org) is a multi-issue research center founded in 1963. The Program on Inequality and the Common Good was founded in 2006 to draw attention to the growing dangers of concentrated wealth and power, and to advocate policies and practices to reverse extreme inequalities in income, wealth, and opportunity. The Inequality.org website (http://inequality.org/) provides an online portal into all things related to the income and wealth gaps that so divide us. -

Current Affairs Capsule for SBI/IBPS/RRB PO Mains Exam 2021 – Part 2

Current Affairs Capsule for SBI/IBPS/RRB PO Mains Exam 2021 – Part 2 Important Awards and Honours Winner Prize Awarded By/Theme/Purpose Hyderabad International CII - GBC 'National Energy Carbon Neutral Airport having Level Airport Leader' and 'Excellent Energy 3 + "Neutrality" Accreditation from Efficient Unit' award Airports Council International Roohi Sultana National Teachers Award ‘Play way method’ to teach her 2020 students Air Force Sports Control Rashtriya Khel Protsahan Air Marshal MSG Menon received Board Puruskar 2020 the award NTPC Vallur from Tamil Nadu AIMA Chanakya (Business Simulation Game)National Management Games(NMG)2020 IIT Madras-incubated Agnikul TiE50 award Cosmos Manmohan Singh Indira Gandhi Peace Prize On British broadcaster David Attenborough Chaitanya Tamhane’s The Best Screenplay award at Earlier, it was honoured with the Disciple Venice International Film International Critics’ Prize awarded Festival by FIPRESCI. Chloe Zhao’s Nomadland Golden Lion award at Venice International Film Festival Aditya Puri (MD, HDFC Bank) Lifetime Achievement Award Euromoney Awards of Excellence 2020. Margaret Atwood (Canadian Dayton Literary Peace Prize’s writer) lifetime achievement award 2020 Click Here for High Quality Mock Test Series for IBPS RRB PO Mains 2020 Click Here for High Quality Mock Test Series for IBPS RRB Clerk Mains 2020 Follow us: Telegram , Facebook , Twitter , Instagram 1 Current Affairs Capsule for SBI/IBPS/RRB PO Mains Exam 2021 – Part 2 Rome's Fiumicino Airport First airport in the world to Skytrax (Leonardo -

Silver Spoon Oligarchs

CO-AUTHORS Chuck Collins is director of the Program on Inequality and the Common Good at the Institute for Policy Studies where he coedits Inequality.org. He is author of the new book The Wealth Hoarders: How Billionaires Pay Millions to Hide Trillions. Joe Fitzgerald is a research associate with the IPS Program on Inequality and the Common Good. Helen Flannery is director of research for the IPS Charity Reform Initiative, a project of the IPS Program on Inequality. She is co-author of a number of IPS reports including Gilded Giving 2020. Omar Ocampo is researcher at the IPS Program on Inequality and the Common Good and co-author of a number of reports, including Billionaire Bonanza 2020. Sophia Paslaski is a researcher and communications specialist at the IPS Program on Inequality and the Common Good. Kalena Thomhave is a researcher with the Program on Inequality and the Common Good at the Institute for Policy Studies. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The authors wish to thank Sarah Gertler for her cover design and graphics. Thanks to the Forbes Wealth Research Team, led by Kerry Dolan, for their foundational wealth research. And thanks to Jason Cluggish for using his programming skills to help us retrieve private foundation tax data from the IRS. THE INSTITUTE FOR POLICY STUDIES The Institute for Policy Studies (www.ips-dc.org) is a multi-issue research center that has been conducting path-breaking research on inequality for more than 20 years. The IPS Program on Inequality and the Common Good was founded in 2006 to draw attention to the growing dangers of concentrated wealth and power, and to advocate policies and practices to reverse extreme inequalities in income, wealth, and opportunity. -

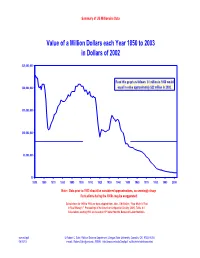

Summary of Millionaire Materials

Summary of US Millionaire Data Value of a Million Dollars each Year 1850 to 2003 in Dollars of 2002 $25,000,000 Read this graph as follows: $1 million in 1850 would $20,000,000 equal in value approximately $22 million in 2002. $15,000,000 $10,000,000 $5,000,000 $0 1850 1860 1870 1880 1890 1900 1910 1920 1930 1940 1950 1960 1970 1980 1990 2000 Note: Data prior to 1913 should be considered approximations, so seemingly sharp fluctuations during the 1800s may be exaggerated. Calculations for 1850 to 1912 use data adapted from John J. McCusker, "How Much Is That in Real Money?," Proceedings of the American Antiquarian Society (2001), Table A-1. Calculations starting 1913 are based on CPI data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics. summill.pdf © Robert C. Sahr, Political Science Department, Oregon State University, Corvallis, OR 97331-6206 06/10/03 e-mail: [email protected]; WWW: http://www.orst.edu/Dept/pol_sci/fac/sahr/sahrhome.html Summary of US Millionaire Data, page 2 Dollars Needed to Equal in Value $1 Million in the Year 2002 for each Year 1850 to 2003 $1,100,000 $1,000,000 $900,000 $800,000 $700,000 Read this graph as follows: To equal the $600,000 value of $1 million in dollars of the year 2002 would have required about $45,000 in 1850. $500,000 $400,000 $300,000 $200,000 $100,000 $0 1850 1860 1870 1880 1890 1900 1910 1920 1930 1940 1950 1960 1970 1980 1990 2000 Note: Data prior to 1913 should be considered approximations, so seemingly sharp fluctuations during the 1800s may be exaggerated. -

The Forbes 400 and the Gates-Buffett Giving Pledge

ACRN Journal of Finance and Risk Perspectives Vol. 4, Issue 1, February 2015, p. 82-101 ISSN 2305-7394 THE FORBES 400 AND THE GATES-BUFFETT GIVING PLEDGE 1 2 4 Kent Hickman , Mark Shrader , Danielle Xu3, Dan Lawson 1,2,3 School of Business Administration, Gonzaga University 4Department of Finance, Indiana University of Pennsylvania Abstract. Large disparities in the distribution of wealth across the world’s population may contribute to political and societal instability. While public policy decisions regarding taxes and transfer payments could lead to more equal wealth distribution, they are controversial. This paper examines a voluntary initiative aimed at wealth redistribution, the Giving Pledge, developed by Warren Buffet and Bill and Melinda Gates. High wealth individuals signing the pledge commit to give at least half of their wealth to charity either over their lifetime or in their will. We attempt to identify personal characteristics of America’s billionaires that influence their decision to sign the pledge. We find several factors that are related to the likelihood of giving, including the individual’s net worth, the source of their wealth, their level of education, their notoriety and their political affiliation. Keywords: Philanthropy, Giving Pledge, Forbes 400, wealth redistribution Introduction The Giving Pledge is an effort to help address society’s most pressing problems by inviting the world’s wealthiest individuals and families to commit to giving more than half of their wealth to philanthropy or charitable causes either during their lifetime or in their will. (The Giving Pledge, 2013). The extremely rich are known to purchase islands, yachts, sports teams and collect art in their pursuit of happiness.