1916 Preparedness Day Bombing

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

S.F.P.L. Historic Photograph Collection Subject Guide

San Francisco Historical Photograph Collection San Francisco History Center Subject Collection Guide S.F.P.L. HISTORIC PHOTOGRAPH COLLECTION SUBJECT GUIDE A Adult Guidance Center AERIAL VIEWS. 1920’s 1930’s (1937 Aerial survey stored in oversize boxes) 1940’s-1980’s Agricultural Department Building A.I.D.S. Vigil. United Nations Plaza (See: Parks. United Nations Plaza) AIRCRAFT. Air Ferries Airmail Atlas Sky Merchant Coast Guard Commercial (Over S.F.) Dirigibles Early Endurance Flight. 1930 Flying Clippers Flying Clippers. Diagrams and Drawings Flying Clippers. Pan American Helicopters Light Military Military (Over S.F.) National Air Tour Over S.F. Western Air Express Airlines Building Airlines Terminal AIRLINES. Air West American British Overseas Airways California Central Canadian Pacific Century Flying A. Flying Tiger Japan Air Lines 1 San Francisco Historical Photograph Collection San Francisco History Center Subject Collection Guide Northwest Orient Pan American Qantas Slick Southwest AIRLINES. Trans World United Western AIRPORT. Administration Building. First Administration Building. Second. Exteriors Administration Building. Second. Interiors Aerial Views. Pre-1937 (See: Airport. Mills Field) Aerial Views. N.D. & 1937-1970 Air Shows Baggage Cargo Ceremonies, Dedications Coast Guard Construction Commission Control Tower Drawings, Models, Plans Fill Project Fire Fighting Equipment Fires Heliport Hovercraft International Room Lights Maintenance Millionth Passenger Mills Field Misc. Moving Sidewalk Parking Garage Passengers Peace Statue Porters Post Office 2 San Francisco Historical Photograph Collection San Francisco History Center Subject Collection Guide Proposed Proposition No. 1 Radar Ramps Shuttlebus Steamers Strikes Taxis Telephones Television Filming AIRPORT. Terminal Building (For First & Second See: Airport. Administration Building) Terminal Building. Central. Construction Dedications, Groundbreaking Drawings, Models, Plans Exteriors Interiors Terminal Building. -

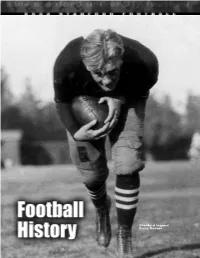

04 FB Guide.Qxp

Stanford legend Ernie Nevers Coaching Records Football History Stanford Coaching History Coaching Records Seasons Coach Years Won Lost Tied Pct. Points Opp. Seasons Coach Years Won Lost Tied Pct. Points Opp. 1891 No Coach 1 3 1 0 .750 52 26 1933-39 C.E. Thornhill 7 35 25 7 .574 745 499 1892, ’94-95 Walter Camp 3 11 3 3 .735 178 89 1940-41 Clark Shaughnessy 2 16 3 0 .842 356 180 1893 Pop Bliss 1 8 0 1 .944 284 17 1942, ’46-50 Marchmont Schwartz 6 28 28 4 .500 1,217 886 1896, 98 H.P. Cross 2 7 4 2 .615 123 66 1951-57 Charles A. Taylor 7 40 29 2 .577 1,429 1,290 1897 G.H. Brooke 1 4 1 0 .800 54 26 1958-62 Jack C. Curtice 5 14 36 0 .280 665 1,078 1899 Burr Chamberlain 1 2 5 2 .333 61 78 1963-71 John Ralston 9 55 36 3 .601 1,975 1,486 1900 Fielding H. Yost 1 7 2 1 .750 154 20 1972-76 Jack Christiansen 5 30 22 3 .573 1,268 1,214 1901 C.M. Fickert 1 3 2 2 .571 34 57 1979 Rod Dowhower 1 5 5 1 .500 259 239 1902 C.L. Clemans 1 6 1 0 .857 111 37 1980-83 Paul Wiggin 4 16 28 0 .364 1,113 1,146 1903-08 James F. Lanagan 6 49 10 5 .804 981 190 1984-88 Jack Elway 5 25 29 2 .463 1,263 1,267 1909-12 George Presley 4 30 8 1 .782 745 159 1989-91 Dennis Green 3 16 18 0 .471 801 770 1913-16 Floyd C. -

Looking Forward: Prediction and Uncertainty in Modern America

Looking Forward Looking Forward Prediction and Uncertainty in Modern America Jamie L. Pietruska The University of Chicago Press Chicago & London The University of Chicago Press, Chicago 60637 The University of Chicago Press, Ltd., London © 2017 by The University of Chicago All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission, except in the case of brief quotations in critical articles and reviews. For more information, contact the University of Chicago Press, 1427 E. 60th St., Chicago, IL 60637. Published 2017 Printed in the United States of America 26 25 24 23 22 21 20 19 18 17 1 2 3 4 5 isbn- 13: 978- 0- 226- 47500- 4 (cloth) isbn- 13: 978- 0- 226- 50915- 0 (e- book) doi: 10.7208/chicago/9780226509150.001.0001 Publication of this book was generously supported with a grant from the Rutgers University Research Council. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Pietruska, Jamie L., author. Title: Looking forward : prediction and uncertainty in modern America / Jamie L. Pietruska. Description: Chicago ; London : The University of Chicago Press, 2017. | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers: LCCN 2017018833 | isbn 9780226475004 (cloth : alk. paper) | isbn 9780226509150 (e-book) Subjects: LCSH: Forecasting—Social aspects—United States. | Economic forecasting— United States. | Risk—United States. | Prophecy. Classification:lcc cb158 .p54 2017 | ddc 330.973/00112—dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017018833 ♾ This paper meets the requirements of ansi/niso z39.48- 1992 (Permanence of Paper). To Jason The present age is in the attitude of looking forward. -

Popular Controversies in World History, Volume Four

Popular Controversies in World History © 2011 ABC-Clio. All Rights Reserved. Volume One Prehistory and Early Civilizations Volume Two The Ancient World to the Early Middle Ages Volume Three The High Middle Ages to the Modern World Volume Four The Twentieth Century to the Present © 2011 ABC-Clio. All Rights Reserved. Popular Controversies in World History INVESTIGATING HISTORY’S INTRIGUING QUESTIONS Volume Four The Twentieth Century to the Present Steven L. Danver, Editor © 2011 ABC-Clio. All Rights Reserved. Copyright 2011 by ABC-CLIO, LLC All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, except for the inclusion of brief quotations in a review, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Popular controversies in world history : investigating history’s intriguing questions / Steven L. Danver, editor. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-1-59884-077-3 (hard copy : alk. paper) — ISBN 978-1-59884-078-0 (ebook) 1. History—Miscellanea. 2. Curiosities and wonders. I. Danver, Steven Laurence. D24.P67 2011 909—dc22 2010036572 ISBN: 978-1-59884-077-3 EISBN: 978-1-59884-078-0 14 13 12 11 1 2 3 4 5 This book is also available on the World Wide Web as an eBook. Visit www.abc-clio.com for details. ABC-CLIO, LLC 130 Cremona Drive, P.O. Box 1911 Santa Barbara, California 93116-1911 This book is printed on acid-free paper Manufactured in the United States of America © 2011 ABC-Clio. -

From Transcendentalism to Progressivism: the Making of an American Reformer, Abby Morton Diaz (1821-1904)

East Tennessee State University Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University Electronic Theses and Dissertations Student Works 5-2006 From Transcendentalism to Progressivism: The Making of an American Reformer, Abby Morton Diaz (1821-1904). Ann B. Cro East Tennessee State University Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.etsu.edu/etd Part of the Women's Studies Commons Recommended Citation Cro, Ann B., "From Transcendentalism to Progressivism: The akM ing of an American Reformer, Abby Morton Diaz (1821-1904)." (2006). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 2187. https://dc.etsu.edu/etd/2187 This Thesis - Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Works at Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. From Transcendentalism to Progressivism: The Making of an American Reformer, Abby Morton Diaz (1821-1904) ____________________ A thesis presented to the faculty of the Department of Cross-Disciplinary Studies East Tennessee State University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts in Liberal Studies ___________________ by Ann B. Cro May 2006 ____________________ Dr. Theresa Lloyd, Chair Dr. Marie Tedesco Dr. Kevin O’Donnell Keywords: Abby Morton Diaz, Transcendentalism, Abolition, Brook Farm, Nationalist Movement ABSTRACT From Transcendentalism to Progressivism: The Making of an American Reformer, Abby Morton Diaz (1821-1904) by Ann B. Cro Author and activist Abby Morton Diaz (1821-1904) was a member of the Brook Farm Transcendental community from 1842 until it folded in 1847. -

Archbishop Edward I Hannah Role As Chairman of the National

Apostle of the Dock: Archbishop Edward J. Hannah’s Role as Chairman of the National Longshoremen’s Board During the 1934 San Francisco Waterfront Strike Jaime Garcia De Alba he Reverend Edward Joseph Hanna (1860-1944) served as Archbishop of San Francisco from 1915 through his retirement in 1935. On June 26 1934, at the height of the San TFrancisco Waterfront/Pacific Coast Longshoremen’s Strike, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt named Archbishop Hanna chairman of the National Longshoremen’s Board (NLB). The significance of Rev. Manna’s role as chairman served as a model of the American Catholic hierarchy’s cooperation with the President and the New Deal. Presidential appointments of Catholic leaders represented a new era for the Church, which viewed the federal government’s depression program as a response to Papal doctrine for social reform. Archbishop Hanna entered as arbiter in the 1934 Strike with a solid record for civil service and moderate support of organized labor. Although Rev. Hanna and the Presidential board contributed minimally after its initial introduction into the conflict between longshoremen and shipping employers, tangled in a seemingly unbreakable stand off by late June 1934, the NLB proved beneficial after both sides agreed to let the board arbitrate their grievances. Archbishop Manna then found an opportunity to demonstrate Catholic doctrine as a guide out of the city’s turmoil, and the board’s potential as an example of Church’s support with the governmental recovery program.1 In 1912, then Archbishop of San Francisco William Patrick Riordan made a considerable effort to appoint Rev. -

Umagazine Umagazine

January - February 2014 Vol. 9, Issue 1 UU (USPS 018-250) Magazine Magazine Wise & Well Dollars & Cents Duck & Cover 100-year-old retiree re- It’s time to send in ap- NLRB decisions put calls a time when plications for Local Walmart on the defen- everything seemed a 324’s Non-Food Schol- sive around the clock. little easier. arship program. Pages 10-11 Page 7 Page 15 Official Publication of the United Food & Commercial Workers Union Local 324 U magazine What’s Inside magazine Labor Relations 4 Worksites continue to promote cooperation. Sec.-Tres. Report 5 Minimum wage hikes long sup- ported by Labor Yesterday’s News Next General Membership 6 Patriotic march turns bloody as in- Meeting is Wednesday, justice prevails. March 12 at 7 p.m. 8530 Stanton Avenue ‘ObamaCare’ Buena Park 8 Contract negotiations include talks about the ACA’s affect. Member Feature Withdrawal Card Request 10 Retired staff member celebrates 100 years, reflects on days past. Change of Address Form Member's name:_______________________________ Hot Topics! 13 Keeping a work journal can help SSN:______________________ DOB:_____________ you keep your job. Address______________________________________ Word on the Street 14 How has the Affordable Care Act affected you or those you know? City_____________________________zip__________ Phone #______________________________________ Editor: Todd Conger UNION OFFICE HOURS Asst. Editor: Mercedes Clarke 8 a.m. to 5 p.m. Monday-Friday email________________________________________ TELEPHONE NUMBERS: Orange County: (714) 995-4601 Lake Forest: (949) 587-9881: Long Beach-Downey- If requesting withdrawal, what was your last day worked? ________ Norwalk Limited Area Toll Free: (800) 244-UFCW MAIN OFFICE: 8530 Stanton Avenue, P.O. -

Fang Family San Francisco Examiner Photograph Archive Negative Files, Circa 1930-2000, Circa 1930-2000

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/hb6t1nb85b No online items Finding Aid to the Fang family San Francisco examiner photograph archive negative files, circa 1930-2000, circa 1930-2000 Bancroft Library staff The Bancroft Library University of California, Berkeley Berkeley, CA 94720-6000 Phone: (510) 642-6481 Fax: (510) 642-7589 Email: [email protected] URL: http://bancroft.berkeley.edu/ © 2010 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Finding Aid to the Fang family San BANC PIC 2006.029--NEG 1 Francisco examiner photograph archive negative files, circa 1930-... Finding Aid to the Fang family San Francisco examiner photograph archive negative files, circa 1930-2000, circa 1930-2000 Collection number: BANC PIC 2006.029--NEG The Bancroft Library University of California, Berkeley Berkeley, CA 94720-6000 Phone: (510) 642-6481 Fax: (510) 642-7589 Email: [email protected] URL: http://bancroft.berkeley.edu/ Finding Aid Author(s): Bancroft Library staff Finding Aid Encoded By: GenX © 2011 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Collection Summary Collection Title: Fang family San Francisco examiner photograph archive negative files Date (inclusive): circa 1930-2000 Collection Number: BANC PIC 2006.029--NEG Creator: San Francisco Examiner (Firm) Extent: 3,200 boxes (ca. 3,600,000 photographic negatives); safety film, nitrate film, and glass : various film sizes, chiefly 4 x 5 in. and 35mm. Repository: The Bancroft Library. University of California, Berkeley Berkeley, CA 94720-6000 Phone: (510) 642-6481 Fax: (510) 642-7589 Email: [email protected] URL: http://bancroft.berkeley.edu/ Abstract: Local news photographs taken by staff of the Examiner, a major San Francisco daily newspaper. -

FREE TOM MOONEY! an EXHIBITION of the Yale Law Library’S Tom Mooney Collection, on the Centennial of Mooney’S Frame-Up FEBRUARY 1 – MAY 27, 2016

FREE TOM MOONEY! AN EXHIBITION of the Yale Law Library’s Tom Mooney Collection, on the centennial of Mooney’s frame-up FEBRUARY 1 – MAY 27, 2016 Curated by LORNE BAIR, Lorne Bair Rare Books HÉLÈNE GOLAY, Lorne Bair Rare Books MIKE WIDENER, Yale Law Library New Haven • Lillian Goldman Law Library, Yale Law School • 2016 1 INTRODUCTION A HUNDRED YEARS AGO, a bomb explosion was the pre- text that San Francisco authorities needed to prosecute the militant left-wing labor organizer Tom Mooney on trumped-up murder charges. Mooney’s false conviction and death sentence set off a 22-year campaign that proved Mooney had been framed, made him one of the world’s most famous Americans, and eventually resulted in his exoneration. The campaign also created an enormous number of print and visual materials, including legal briefs, books, pamphlets, movies, flyers, stamps, poetry, and music. The examples in this exhibition are only a few of the over 150 items in Yale Law Library’s collection on the Mooney case, housed in the Rare Book Collection. They form a rich re- source for studying the Mooney case, the American Left in the interwar years, and the emergence of modern media campaigns. Unless otherwise noted, all items are from the Rare Book Collection, Lillian Goldman Law Library, Yale Law School. Theodore Dreiser, Tom Mooney (San Francisco: Local no. 17, Amalgamated Lithographers of America, undated). 2 Burnett G. Haskell. Broadside circular issued by the International Workmen’s Association. San Francisco, 1881. Reproduction of original, courtesy of Yale Collection of Western Americana, Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library. -

5-2 • 3-1 Pac-12) (4-2 • 2-2 Pac-12) Live Stats

Stanford Cardinal Game Information Date ...................................................................... Saturday, Oct. 22 4-2 overall • 2-2 Pac-12 Time .................................................................................... Noon PT Date Opponent Time • Result Location ......................Stanford, Calif. • Stanford Stadium (50,424) 9.2 Kansas State [FS1] ............................................. W, 26-13 Television ..............................................................Pac-12 Networks 9.17 USC* [ABC] ......................................................... W, 27-10 Greg Wolf, Glenn Parker, Jill Savage 9.24 at UCLA* [ABC] ................................................... W, 22-13 Stanford Radio ......................................................... KNBR 1050 AM 9.30 at #10/9 Washington* [ESPN] ...............................L, 6-44 Colorado Stanford Scott Reiss ’93, Todd Husak ’00 and John Platz ’84 10.8 Washington State* [ESPN] ..................................L, 16-42 Stanford Student Radio .............................................KZSU 90.1 FM 10.15 at Notre Dame [NBC] ......................................... W, 17-10 Buffaloes Cardinal National Radio ................................................... Sirius 145 • XM 197 10.22 Colorado* [Pac-12 Networks] ................................ Noon (5-2 • 3-1 Pac-12) (4-2 • 2-2 Pac-12) Live Stats ...............................................................GoStanford.com 10.29 at Arizona* ............................................................ -

University of Pardubice Faculty of Arts and Philosophy Mccarthyism in Hollywood Deni Pitarka Bachelor Thesis 2019

University of Pardubice Faculty of Arts and Philosophy McCarthyism in Hollywood Deni Pitarka Bachelor Thesis 2019 2 3 Acknowledgement I would like to express my gratitude to my supervisor, Mgr. Michal Kleprlík, Ph.D., for his valuable comments and advice he provided for this thesis. I would also like to thank my family for their support. 4 Prohlášení Prohlašuji, že jsem bakalářskou práci vypracoval samostatně, že jsem řádně citoval všechny použité prameny a literaturu a že práce nebyla využita v rámci jiného vysokoškolského studia či k získání jiného nebo stejného titulu. Byl jsem obeznámen, že se na moji akademickou práci vztahují práva a povinnosti vyplývající ze zákona č. 121/2000 Sb., autorský zákon a zejména se skutečností, že Univerzita Pardubice má právo na uzavření licenční smlouvy o užití této práce jako školního díla podle § 60odst. 1 autorského zákona, a s tím, že pokud dojde k užití této práce mnou nebo bude poskytnuta licence o užití jinému subjektu, je Univerzita Pardubice oprávněna ode mne požadovat přiměřený příspěvek na úhradu nákladů, které na vytvoření díla vynaložila, a to podle okolností až do jejich skutečné výše. Beru dále na vědomí, že v souladu s § 47b Zákona č.111/1998 Sb., o vysokých školách a o změně a doplnění dalších zákonů (zákon o vysokých školách) ve znění pozdějších předpisů, a směrnicí Univerzity Pardubice č. 9/2012, bude práce zveřejněna v Univerzitní knihovně a prostřednictvím Digitální knihovny Univerzity Pardubice V Pardubicích, dne 31. prosince 2018 ………………………….. Deni Pitarka 5 ANNOTATION The Bachelors thesis concerns the phenomenon Red Scare and the House of Un-American Activities Committee, which was established in 1938 to investigate communism activity within the United States of America. -

Oliver Wendell Holmes, the Abrams Case, and the Origins of the Harmless Speech Tradition

SCHAUER (DO NOT DELETE) 10/13/2020 10:35 PM Oliver Wendell Holmes, the Abrams Case, and the Origins of the Harmless Speech Tradition Frederick Schauer* I. INTRODUCTION: THE OTHER PARAGRAPH(S) ..................................................... 205 II. THE FACTS ............................................................................................................... 207 III. THE URGE TO TRIVIALIZE .................................................................................... 214 IV. THE “HARMLESS SPEECH” TRADITION .............................................................. 218 V. CONCLUSION ............................................................................................................. 223 I. INTRODUCTION: THE OTHER PARAGRAPH(S) For over a century now, abundant attention, almost all of it positive, has been paid to the magisterial final paragraph of Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr.’s dissenting opinion in Abrams v. United States.1 It was here that Holmes observed that “time has upset many fighting faiths,”2 that “the best test of the truth is the power of the thought to get itself accepted in the competition of the market,”3 and that the Constitution “is an experiment, as all life is an experiment,”4 among the many ideas packed into this one modestly-sized paragraph. All the praise appropriately lavished upon this paragraph has had the effect, however, of deflecting attention from the remainder of Holmes’s opinion. More specifically, the common focus on the final paragraph has obscured Holmes’s observation four paragraphs earlier *David and Mary Harrison Distinguished Professor of Law, University of Virginia. This Article is the written and referenced version of my contribution to the Symposium on “Abrams at 100: A Reassessment of Holmes’s ‘Great Dissent’” held at the Columbia Law School on November 8, 2019. 1 250 U.S. 616, 630–31 (1919) (Holmes, J., dissenting). The well-known exception to my characterization of the attention to Holmes’s Abrams dissent as “positive” is John H.