Visualized Combinatorics, Jan Andres

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ONLINE AUCTION: Thursday, Nov

ONLINE AUCTION: Thursday, Nov. 12th, 2020 from 4 - 10 p.m. INSTRUCTIONS AND BIDDING BOOK About the Lynn Institute: The Lynn Institute for Healthcare Research, a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization, is committed to helping communities, neighborhoods, and vulnerable populations with health and lifestyle conditions that are impacting overall health. We identify at-risk populations, define unique health risks, publish findings, assemble collaboratives, create programs and develop sustainable plans with measurable goals and objectives to improve the health and hope of communities. Our Work Includes: Research Studies / Outcome-Based Initiatives Collaboratives Community Impact & Engagement - Zoo4U & Science4U Health & Lifestyle Programs: ¡ Count Me In 4 Kids ¡ HealthRide OKC / Prescription Co-Pay Assistance ¡ Foundations of Wellness / On the Road to Health Classes ¡ Planting Urban Gardens ¡ Health Screenings ¡ Food distributions of fresh produce and lean meats for nutrition and health; (Since August 2019, the Lynn Institute has distributed more than 350,000 pounds of fresh produce to impoverished neighborhoods in the OKC metro.) HOW CAN YOU HELP? It requires funding to offer the programs and provide impoverished communities access to basic life needs that most of us take for granted. ¡ Please take the opportunity this Thursday, November 12th from 4 – 10 p.m. to bid on and buy the incredible works of art that have been generously created by artists from around the state; ¡ Not bidding? You can still donate to the Lynn Institute on the auction site; and, ¡ Visit our Chairity partner, the North Gallery & Studios in the Shoppes at Northpark or the other galleries around our state where our individual artists show their work. -

The Destruction of Art

1 The destruction of art Solvent form examines art and destruction—through objects that have been destroyed (lost in fires, floods, vandalism, or, similarly, those that actively court or represent this destruction, such as Christian Marclay’s Guitar Drag or Chris Burden’s Samson), but also as an undoing process within art that the object challenges through form itself. In this manner, events such as the Momart warehouse fire in 2004 (in which large hold- ings of Young British Artists (YBA) and significant collections of art were destroyed en masse through arson), as well as the events surrounding art thief Stéphane Breitwieser (whose mother destroyed the art he had stolen upon his arrest—putting it down a garbage disposal or dumping it in a nearby canal) are critical events in this book, as they reveal something about art itself. Likewise, it is through these moments of destruction that we might distinguish a solvency within art and discover an operation in which something is made visible at a time when art’s metaphorical undo- ing emerges as oddly literal. Against this overlay, a tendency is mapped whereby individuals attempt to conceptually gather these destroyed or lost objects, to somehow recoup them in their absence. This might be observed through recent projects, such as Jonathan Jones’s Museum of Lost Art, the Tate Modern’s Gallery of Lost Art, or Henri Lefebvre’s text The Missing Pieces; along with exhibitions that position art as destruction, such as Damage Control at the Hirschhorn Museum or Under Destruction by the Swiss Institute in New York. -

Ðрт Ðÿðµð¿Ñšñ€ Ðлбуð¼ ÑпиÑÑšðº (Ð ´Ð¸Ñ

ÐÑ €Ñ‚ Пепър ÐÐ »Ð±ÑƒÐ¼ ÑÐ ¿Ð¸ÑÑ ŠÐº (Ð ´Ð¸ÑÐ ºÐ¾Ð³Ñ€Ð°Ñ„иÑÑ ‚а & график) Straight Life https://bg.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/straight-life-1446067/songs So in Love https://bg.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/so-in-love-28452495/songs https://bg.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/art-pepper-with-warne-marsh- Art Pepper with Warne Marsh 2864557/songs New York Album https://bg.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/new-york-album-27818530/songs Modern Art https://bg.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/modern-art-11784473/songs Living Legend https://bg.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/living-legend-3257150/songs Popo https://bg.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/popo-1765447/songs Art 'n' Zoot https://bg.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/art-%27n%27-zoot-27818837/songs The Return of Art Pepper https://bg.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/the-return-of-art-pepper-9358181/songs Tokyo Debut https://bg.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/tokyo-debut-3530519/songs Art Pepper with Duke Jordan in Copenhagen https://bg.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/art-pepper-with-duke-jordan-in- 1981 copenhagen-1981-27818796/songs The Trip https://bg.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/the-trip-3523093/songs Art Pepper Today https://bg.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/art-pepper-today-3530231/songs The Art Pepper Quartet https://bg.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/the-art-pepper-quartet-3519815/songs Smack Up https://bg.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/smack-up-609881/songs The Early Show https://bg.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/the-early-show-1764297/songs Intensity -

NOTICE of PUBLIC MEETING February 2, 2017 9 A.M. to 3 P.M. Warehouse Artist Lofts Community Room 1108 R St. Sacramento, CA 95811 (916) 498-9033

NOTICE OF PUBLIC MEETING February 2, 2017 9 a.m. to 3 p.m. Warehouse Artist Lofts Community Room 1108 R St. Sacramento, CA 95811 (916) 498-9033 1. 9:00 Call to Order D. Harris Welcome by Warehouse Artist Lofts J. Kinloch 2. 9:10 Roll Call and Establishment of a Quorum M. Moscoso 3. 9:15 Approval of Minutes from September 21 & 22 and December 15, 2016 D. Harris (TAB P) 4. 9:20 Chair’s Report (TAB Q) D. Harris 5. 9:30 Director’s Report (TAB R) C. Watson 6. 9:40 2016-2017 Programs—Voting Items S. Gilbride a. Professional Development and Consulting Panel Recommendations (TAB S) b. Spring 2017 Panel Pool (TAB T) c. State-Local Partnership Grant Guidelines (TAB U) 7. 10:20 Legislative Update K. Margolis C. Watson 8. 10:40 Warehouse Artist Lofts Tour J. Kinloch 9. 11:10 Oakland Ghost Ship Fire and Artist Housing (TAB V) C. Watson 10. 12:10 Working Lunch D. Harris 11. 12:40 Create CA Update P. Wayne 12. 1:00 Office of Health Equity Collaboration: Introduction and Status A. Kiburi 13. 1:20 Public Comment (may be limited to 2 minutes each) D. Harris 14. 1:50 Election of 2017 Officers J. Devis 15. 2:00 Council Member Reports D. Harris 16. 2:30 Adjournment : In memory of Howard Bingham (TAB D. Harris W) Notes: 1. All times indicated and the orders of business are approximate and subject to change. 2. Any item listed on the Agenda is subject to possible Council action. -

Art + Nature Mission

2014–2015 ANNUAL REPORT ART + NATURE MISSION TO ENRICH LIVES THROUGH EXCEPTIONAL EXPERIENCES WITH 4 Dynamic Artworks + Vibrant Displays 28 Art Acquisition Highlights 6 Unique Experiences + Unexpected Events 32 Full List of Fiscal Year 2014–2015 Acquisitions 10 Innovative Design + Visionary Ideas 42 Financial Statement 12 Inspiring Curiosity + Exploring Environments 44 Donors 14 Eclectic Exhibitions + Artistic Expressions 50 IMA Board of Governors 18 From the Chair 51 IMA Affiliate Group Leadership 20 From the Melvin & Bren Simon Director and CEO 52 IMA Staff 24 Spectacular Views + Growing Impact 56 Global Impact 27 Garden Acquisition Highlights 58 Photo Credits IMA 2014–2015 ANNUAL REPORT 1 The IMA is committed to enhancing its Gardens and Park so guests will enjoy an exceptional experience in nature. 2 ART + NATURE Dynamic Artworks + Vibrant Displays With a new mission to provide exceptional experiences both inside and out, the IMA put plans in place to transform its Gardens and enhance its Park for a better guest experience. The creation of a lush, verdant perimeter of more than 2,200 plants, shrubs, and trees—including 18 selections never before seen in the Gardens—was a major focus in 2015. This spring you will see the spectacular results—a beautiful display of color—the result of planting 23,000 tulip bulbs, more than any previous year. As part of the enhanced experience, guests are greeted at the Welcome Center and walk along the Garden Path to access the outdoor campus. A new eco-friendly Garden Tram, The Late Miss Kate, given in memory of Katie Sutphin, tours guests around the 52-acre oasis. -

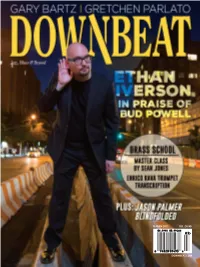

Downbeat.Com March 2021 U.K. £6.99

MARCH 2021 U.K. £6.99 DOWNBEAT.COM MARCH 2021 DOWNBEAT 1 March 2021 VOLUME 88 / NUMBER 3 President Kevin Maher Publisher Frank Alkyer Editor Bobby Reed Reviews Editor Dave Cantor Contributing Editor Ed Enright Creative Director ŽanetaÎuntová Design Assistant Will Dutton Assistant to the Publisher Sue Mahal Bookkeeper Evelyn Oakes ADVERTISING SALES Record Companies & Schools Jennifer Ruban-Gentile Vice President of Sales 630-359-9345 [email protected] Musical Instruments & East Coast Schools Ritche Deraney Vice President of Sales 201-445-6260 [email protected] Advertising Sales Associate Grace Blackford 630-359-9358 [email protected] OFFICES 102 N. Haven Road, Elmhurst, IL 60126–2970 630-941-2030 / Fax: 630-941-3210 http://downbeat.com [email protected] CUSTOMER SERVICE 877-904-5299 / [email protected] CONTRIBUTORS Senior Contributors: Michael Bourne, Aaron Cohen, Howard Mandel, John McDonough Atlanta: Jon Ross; Boston: Fred Bouchard, Frank-John Hadley; Chicago: Alain Drouot, Michael Jackson, Jeff Johnson, Peter Margasak, Bill Meyer, Paul Natkin, Howard Reich; Indiana: Mark Sheldon; Los Angeles: Earl Gibson, Sean J. O’Connell, Chris Walker, Josef Woodard, Scott Yanow; Michigan: John Ephland; Minneapolis: Andrea Canter; Nashville: Bob Doerschuk; New Orleans: Erika Goldring, Jennifer Odell; New York: Herb Boyd, Bill Douthart, Philip Freeman, Stephanie Jones, Matthew Kassel, Jimmy Katz, Suzanne Lorge, Phillip Lutz, Jim Macnie, Ken Micallef, Bill Milkowski, Allen Morrison, Dan Ouellette, Ted Panken, Tom Staudter, Jack Vartoogian; Philadelphia: Shaun Brady; Portland: Robert Ham; San Francisco: Yoshi Kato, Denise Sullivan; Seattle: Paul de Barros; Washington, D.C.: Willard Jenkins, John Murph, Michael Wilderman; Canada: J.D. Considine, James Hale; France: Jean Szlamowicz; Germany: Hyou Vielz; Great Britain: Andrew Jones; Portugal: José Duarte; Romania: Virgil Mihaiu; Russia: Cyril Moshkow. -

Conference Proceedings Re:Live

Re:live MEDIA ART HISTORY 09 Third International Conference on the Histories of Media Art, Science and Technology Conference Proceedings Re:live Media Art Histories 2009 Refereed Conference Proceedings Edited by Sean Cubitt and Paul Thomas 2009 ISBN: [978-0-9807186-3-8] Re:live Media Art Histories 2009 conference proceedings 1 Edited by Sean Cubitt and Paul Thomas for Re:live 2009 Published by The University of Melbourne & Victorian College of the Arts and Music 2009 ISBN: [978-0-9807186-3-8] All papers copyright the authors This collection licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial 2.5 Australia License. Supported by Reviews Panel Su Ballard Thomas Mical Andres Burbano Lissa Mitchell Dimitris Charitos Lizzie Muller martin constable Anna Munster Sara Diamond Daniel Palmer Gabriel Menotti Gonring Ana Peraica Monika Gorska-Olesinska Mike Phillips Mark Guglielmetti melinda rackham Cat Hope stefano raimondi Slavko Kacunko Margit Rosen Denisa Kera Christopher Salter Ji-hoon Kim Morten Søndergaard Mike Leggett Robert Sweeny Frederik Lesage Natasha Vita-More Maggie Macnab danielle wilde Leon Marvell Suzette Worden Re:live Media Art Histories 2009 conference proceedings 2 CONTENTS Susan Ballard_____________________________________________________________________6 Erewhon: framing media utopia in the antipodes Andres Burbano__________________________________________________________________12 Between punched film and the first computers, the work of Konrad Zuse Anders Carlsson__________________________________________________________________16 -

TEFAF Catalogue, Entitled Kuon (Aetus), Is the Second Year and Tomorrow

山路を登りながら TEFAF Maastricht 2019 16th March – 24th March 2019 Early Access Day (Invite only) 14th March Preview Day (Invite only) 15th March Stand 237 The Yufuku Collection 2019 Sueharu Fukami Masaru Nakada 06 58 Our Raison D'etre 10 Satoru Ozaki 62 Sachi Fujikake In recent years, the emergence of a group of Japanese artists who have spearheaded a new way of thinking Masaaki Yonemoto Kosuke Kato 14 66 in the realm of contemporary art has helped to shift paradigms and vanquish stereotypes borne from the 19th century, their art and aesthetics understood as making vital contributions to the broader history of modern and contemporary art. This new current, linked by the phrase Keisho-ha (School of Form), Keizo Sugitani Ayane Mikagi 18 70 encompasses a movement of artists who, through the conscious selection of material and technique, create boldly innovative sculptures and paintings that cannot be manifested by other means. The term craft does not encapsulate or faithfully capture this movement, nor do the traditional dichotomies that have long Kentaro Sato Hidenori Tsumori 22 74 separated fine art from craft art. To borrow the words of Nietzsche, "Craft is dead." A new age beckons. No country exemplifies this expanding role more so than the artists of contemporary Japan, a country that Ken Mihara Naoki Takeyama 26 78 continues to place premium on elegance in execution coupled with cutting-edge innovation within tradition. No gallery represents this new movement more so than Yufuku, a gallery that has nurtured and represented the Keisho School from its conceptual inception. 30 Akihiro Maeta 82 Yoshiro Kimura Michelangelo once said, "every block of stone has a statue inside, and it is the task of the sculptor to discover it." Our artists are no different, wielding material and technique to create a unique aesthetic that 34 Niyoko Ikuta 86 Yasutaka Baba can inspire future generations, yet would resonate with generations before us, regardless of age, creed or culture. -

Art Pepper Goin' Home Mp3, Flac, Wma

Art Pepper Goin' Home mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Jazz Album: Goin' Home Country: Italy Released: 1983 Style: Bop, Post Bop MP3 version RAR size: 1843 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1699 mb WMA version RAR size: 1332 mb Rating: 4.8 Votes: 749 Other Formats: MP1 WAV AUD AC3 AIFF MP3 ASF Tracklist Hide Credits Goin' Home A1 5:28 Arranged By – George CablesComposed By – Trad.* Samba Mom Mom A2 4:53 Composed By – Art Pepper In A Mello Tone A3 5:30 Composed By – Duke Ellington, Milt Gabler Don't Let The Sun Catch You Cryin' A4 4:57 Composed By – Joe Greene Isn't She Lovely B1 4:10 Composed By – Stevie Wonder Billie's Bounce B2 3:55 Composed By – Charlie Parker Lover Man B3 4:57 Composed By – Davis*, Sherman*, Ramirez* The Sweetest Sounds B4 5:03 Composed By – Richard Rodgers Companies, etc. Marketed By – Fonit Cetra Credits Alto Saxophone – Art Pepper (tracks: A2, A4, B1, B2, B4) Art Direction – Phil Carroll Clarinet – Art Pepper (tracks: A1, A3, B1, B3) Engineer – Baker Bigsby Engineer [Assistant] – Gary Hobish, Kirk Felton Liner Notes – Laurie Pepper Mastered By – George Horn Photography By [Back Cover] – Phil Bray Photography By [Cover] – K. Abé* Piano – George Cables Producer – Ed Michel Notes Digital recording. Recorded May 11-12, 1982 at Fantasy Studios, Berkeley. Mastered at Fantasy Studios, Berkeley. ℗ 1982 Galaxy Records Tenth & Parker Berkeley, CA 94710 Other versions Category Artist Title (Format) Label Category Country Year Art Pepper / Art Pepper / GXY-5143, George Cables - Galaxy, GXY-5143, George France 1982 68.135 -

Essay 6 Jazz's Use of Classical Music Table of Contents Introduction

1 Essay 6 Jazz’s Use of Classical Music Table of Contents Introduction -1 1st Jazz Recording - 5 Articles - 18 Influence of Jazz in Europe and World - 70 Debussy - 79 & 100 In other Countries - 119 Jazz Arrives at Operas - 162 St Agnes, jazz opera - 213 Introduction Jazz, through its history, has progressed past a number of evolutions; it has had its influences and had both a musical and social background. History never begins or stops at a definite time, nor is it developed by one individual. Growth happens by various situations and experimentation and by creative people. Jazz is a style and not a form. Styles develop and forms are created. Thus jazz begins when East meets West. Jazz evolved in the U.S. with the environment of the late 19th and early 20th century; the music system of Europe, and Africa (with influence of Arab music with the rhythms of the native African. The brilliant book “Post & Branches of Jazz” by Dr. Lloyd C. Miller describes the musical cultures that brought their styles that combined to produce jazz. The art of jazz is over 100 years old now and we have the gift of time to examine the past and by careful research and thought we can produce more accurate conclusions of jazz’s past influences. Jazz could not have developed anywhere but the U.S. In his article” Jazz – The National Anthem” by Frank Patterson in the May 4th, 1922 Musical Courier we read: “Is it Americanism? Well, that is a fine point of contention. There are those who say it is not, that it expresses nothing of the American character; that it is exotic, African Oriental, what not. -

Collaborative Cybercommunities of Internet Musicians Trevor S

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2009 Virtual Garage Bands: Collaborative Cybercommunities of Internet Musicians Trevor S. Harvey Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF MUSIC VIRTUAL GARAGE BANDS: COLLABORATIVE CYBERCOMMUNITIES OF INTERNET MUSICIANS By TREVOR S. HARVEY A Dissertation submitted to the College of Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Degree Awarded: Fall Semester, 2009 Copyright © 2009 Trevor S. Harvey All Rights Reserved The members of the committee approve the dissertation of Trevor S. Harvey, defended on Thursday, October 15, 2009. _________________________________________ Frank Gunderson Professor Directing Dissertation _________________________________________ Gary Burnett University Representative _________________________________________ Michael B. Bakan Committee Member _________________________________________ Stephen McDowell Committee Member The Graduate School has verified and approved the above-named committee members. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Like the many songs discussed within these pages, this dissertation is the result of a large collaborative effort. This research was only possible because of the kindness and warmth of the many members of iCompositions who have taken the time to respond to my many questions on chat, in email, and over Skype and who have given me permission to use their works in this research project. As with any musical collaboration, remix, or cover song, I am merely adding my voice to those that have already been expressed in text and song in hopes that I might somehow enhance what has already been said. First, I am grateful to powermac99 for his support of my research on his website over the past several years. -

Art Lives Here

2007 annual report ART LIVES HERE 2007 annual report | 3 74623 MAM AR07-Body.indd 3 2/21/08 5:16:59 PM 4 | 74623 MAM AR07-Body.indd 4 2/21/08 5:17:45 PM contents 6 Board of Trustees 6 Committees of the Board of Trustees 8 President and Chairperson’s Report 10 Director’s Report 13 Curatorial Report 17 Exhibitions, Traveling Exhibitions 17 Publications 18 Loans 20 Acquisitions 28 Attendance 29 Education and Public Programs 31 Year in Review 35 Development 38 Donors 44 Support Groups 49 Support Group Offi cers 52 Staff 54 Financial Report 54 Financial Statements FRONT AND BACK COVER Roy Lichtenstein, Imperfect Diptych 57 ³⁄₈ × 93 ¾", 1988. Woodcut, screenprint, and collage on board. Gift of Rockwell Automation M2007.34 PAGE 2 William Klein, Man under El, New York, 1955 (detail). Gelatin silver print. Purchase, Richard and Ethel Herzfeld Foundation Acquisition Fund M2007.44 PAGE 3 James Siena, Ten to the Minus Thirty First, 2006 (detail). Enamel on aluminum. Purchase, with funds from the Contemporary Art Society M2007.10 LEFT Saul Leiter, Snow, 1960 (detail). Silver dye bleach print, printed later. Purchase, Richard and Ethel Herzfeld Foundation Acquisition Fund M2006.27 Unless otherwise noted, all photography of works in the Collection is by John Glembin. 74623 MAM AR07-Body.indd 5 2/21/08 5:18:10 PM board of trustees Through August 31, 2007 BOARD OF TRUSTEES COMMITTEES OF THE Earlier European DEVELOPMENT COMMITTEE Sheldon B. Lubar BOARD OF TRUSTEES Arts Committee Ellen Glaisner Chairperson EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE Jim Quirk W. Kent Velde W.