Contemporary Confessional Commitment: a Models-Based Approach with a Particular Focus on Global South Lutheranism

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Free Church Tradition and Worship* I ~Ssl!ME That It Is Corporate and Pu~Lic Wor~Hip That I.S Primarily III Nund

The Free Church Tradition and Worship* I ~SSl!ME that it is corporate and pu~lic wor~hip that i.s primarily III nund. Our fathers used to call It "SOCIal worship" and r wonder whether any significance attaches to the fact Ijjhat we now caU it ." public worship." :At this point, as with our doctrinal in heritance, we are part of the fruit of the great RefoTInation mo~ ment of the 16th century and the heirs not of one but of several of the great reformers of that century. Our heritage is a varied and complex one. It is this which accounts both for its strength and its weakness. First and foremost comes our debt to Luther. For 'IJhe mediaeval Church the Mass was the centre and climax of worship. It had become by the 16th century-in the words of W. D. Maxwell "a dramatic spectacle, culminating not in communion but in [lhe miracle of transubstantiation" (An Outline of Christian Worship, 1939 edition, p. 72). The service was said ~naudibly in a rtongue of which few even df the priests remained really masters. Many of the latter were illiterate and the sermon had long fallen into general disuse. The great contribution of the dynamic 'Luther was to restore the vernacular as the medium of worship. His German Bible and his German IMass sett the pattern for many other lands and races besides the German, among them our own. But Luther did more than Ithat. He revised the Roman service of Mass in the interests of gospel purity and then, perhaps less soundly in the long run, asa medium of instruction. -

Modelling and Control Methods with Applications to Mechanical Waves

Digital Comprehensive Summaries of Uppsala Dissertations from the Faculty of Science and Technology 1174 Modelling and Control Methods with Applications to Mechanical Waves HANS NORLANDER ACTA UNIVERSITATIS UPSALIENSIS ISSN 1651-6214 ISBN 978-91-554-9023-2 UPPSALA urn:nbn:se:uu:diva-229793 2014 Dissertation presented at Uppsala University to be publicly examined in room 2446, ITC, Lägerhyddsvägen 2, Uppsala, Friday, 17 October 2014 at 10:15 for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. The examination will be conducted in English. Faculty examiner: Prof. Jonas Sjöberg (Chalmers). Abstract Norlander, H. 2014. Modelling and Control Methods with Applications to Mechanical Waves. Digital Comprehensive Summaries of Uppsala Dissertations from the Faculty of Science and Technology 1174. 72 pp. Uppsala: Acta Universitatis Upsaliensis. ISBN 978-91-554-9023-2. Models, modelling and control design play important parts in automatic control. The contributions in this thesis concern topics in all three of these concepts. The poles are of fundamental importance when analyzing the behaviour of a system, and pole placement is an intuitive and natural approach for control design. A novel parameterization for state feedback gains for pole placement in the linear multiple input case is presented and analyzed. It is shown that when the open and closed loop poles are disjunct, every state feedback gain can be parameterized. Other properties are also investigated. Hammerstein models have a static non-linearity on the input. A method for exact compensation of such non-linearities, combined with introduction of integral action, is presented. Instead of inversion of the non-linearity the method utilizes differentiation, which in many cases is simpler. -

Protestant Scholasticism: Essays in Reassessment

PROTESTANT SCHOLASTICISM: ESSAYS IN REASSESSMENT Edited by Carl R. Trueman and R. Scott Clark paternoster press GRACE COLLEGE & THEO. SEM. Winona lake, Indiana Copyright© 1999 Carl R. Trueman and R. Scott Clark First published in 1999 by Paternoster Press 05 04 03 02 01 00 99 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Paternoster Press is an imprint of Paternoster Publishing, P.O. Box 300, Carlisle, Cumbria, CA3 OQS, U.K. http://www.paternoster-publishing.com The rights of Carl R. Trueman and R. Scott Clark to be identified as the Editors of this Work has been asserted by them in accordance with Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1998. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher or a licence permitting restricted copying. In the U.K. such licences are issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency, 90 Tottenham Court Road, London WlP 9HE. British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library ISBN 0-85364-853-0 Unless otherwise stated, Scripture quotations are taken from the / HOLY BIBLE, NEW INTERNATIONAL VERSION Copyright© 1973, 1978, 1984 by the International Bible Society. Used by permission of Hodder and Stoughton Limited. All rights reserved. 'NIV' is a registered trademark of the International Bible Society UK trademark number 1448790 Cover Design by Mainstream, Lancaster Typeset by WestKey Ltd, Falmouth, Cornwall Printed in Great Britain by Caledonian International Book Manufacturing Ltd, Glasgow 2 Johann Gerhard's Doctrine of the Sacraments' David P. -

Design Analysis Method for Multidisciplinary Complex Product Using Sysml

MATEC Web of Conferences 139, 00014 (2017) DOI: 10.1051/matecconf/201713900014 ICMITE 2017 Design Analysis Method for Multidisciplinary Complex Product using SysML Jihong Liu1,*, Shude Wang1, and Chao Fu1 1 School of Mechanical Engineering and Automation, Beihang University, 100191 Beijing, China Abstract. In the design of multidisciplinary complex products, model-based systems engineering methods are widely used. However, the methodologies only contain only modeling order and simple analysis steps, and lack integrated design analysis methods supporting the whole process. In order to solve the problem, a conceptual design analysis method with integrating modern design methods has been proposed. First, based on the requirement analysis of the quantization matrix, the user’s needs are quantitatively evaluated and translated to system requirements. Then, by the function decomposition of the function knowledge base, the total function is semi-automatically decomposed into the predefined atomic function. The function is matched into predefined structure through the behaviour layer using function-structure mapping based on the interface matching. Finally based on design structure matrix (DSM), the structure reorganization is completed. The process of analysis is implemented with SysML, and illustrated through an aircraft air conditioning system for the system validation. 1 Introduction decomposition and function modeling, function structure mapping and evaluation, and structure reorganization. In the process of complex product design, system The whole process of the analysis method is aimed at engineering is a kind of development methods which providing designers with an effective analysis of ideas covers a wide range of applications across from system and theoretical support to reduce the bad design and requirements analysis, function decomposition to improve design efficiency. -

Georg Mancelius Teoloogina Juhendatud Disputatsioonide Põhjal

Tartu Ülikool Usuteaduskond MERLE KAND GEORG MANCELIUS TEOLOOGINA JUHENDATUD DISPUTATSIOONIDE PÕHJAL magistritöö juhendaja MARJU LEPAJÕE, MA Tartu 2010 Sisukord SISSEJUHATUS .................................................................................................... 4 TÄNU ..................................................................................................................... 9 I. LUTERLIK ORTODOKSIA............................................................................. 10 1.1. Ajastu üldiseloomustus .............................................................................. 10 1.1.1. Ajalooline ülevaade ............................................................................ 10 1.1.2. Ortodoksia tekkepõhjused................................................................... 13 1.2. Luterlik ortodoksia..................................................................................... 14 1.2.1. Periodiseering, tähtsamad esindajad ning koolkonnad....................... 14 1.2.2. Luterliku ortodoksia teoloogilised põhijooned ................................... 17 1.2.2.1. Pühakiri........................................................................................ 17 1.2.2.2. Õpetus Jumalast ........................................................................... 19 1.2.2.3. Loomisest ja inimese pattulangemisest........................................ 22 1.2.2.4. Ettehooldest ja ettemääratusest.................................................... 23 1.2.2.5. Vabast tahtest.............................................................................. -

The Book of Concord FAQ God's Word

would be no objective way to make sure that there is faithful teaching and preaching of The Book of Concord FAQ God's Word. Everything would depend on each pastor's private opinions, subjective Confessional Lutherans for Christ’s Commission interpretations, and personal feelings, rather than on objective truth as set forth in the By permission of Rev. Paul T. McCain Lutheran Confessions. What is the Book of Concord? Do all Lutheran churches have the same view of the Book of Concord? The Book of Concord is a book published in 1580 that contains the Lutheran No. Many Lutheran churches in the world today have been thoroughly influenced by the Confessions. liberal theology that has taken over most so-called "mainline" Protestant denominations in North America and the large Protestant state churches in Europe, Scandinavia, and elsewhere. The foundation of much of modern theology is the view that the words of What are the Lutheran Confessions? the Bible are not actually God's words but merely human opinions and reflections of the The Lutheran Confessions are ten statements of faith that Lutherans use as official ex- personal feelings of those who wrote the words. Consequently, confessions that claim planations and summaries of what they believe, teach, and confess. They remain to this to be true explanations of God's Word are now regarded more as historically day the definitive standard of what Lutheranism is. conditioned human opinions, rather than as objective statements of truth. This would explain why some Lutheran churches enter into fellowship arrangements with What does Concord mean? non-Lutheran churches teaching things in direct conflict with the Holy Scriptures and the Concord means "harmony." The word is derived from two Latin words and is translated Lutheran Confessions. -

6. Confessional Subscription Robert Preus, Ph.D., D

FAITHFUL COMFESSI0Nt"P~LIFE IN THE CHURCH 6. Confessional Subscription Robert Preus, Ph.D., D. Theol. What is a Lutheran? What is the nature of subscription to the Lutheran Confessions? These two questions which are often considered together and which are as inseparably related as Siamese twins have become increasingly important in our day when Lutheranism is fighting for its identity and life. Today most of the Lutheran pastors and teachers throughout the world sub- scribe, at least pro forma, all the confessions of the Evangelical Lutheran church: the ancient catholic creeds and the great Lutheran confessions of the 16th century, i.e. the Augsburg Confession, the Apology of the Augsburg Confession, Luther's two catechisms, the Smalcald Articles and the Formula of Concord. What does such subscription mean? Is such subscription any longer possible in our day of academic freedom and vaunted autonomy, ecu- menisin and dialogue? Many today think that subscription to any creed or confession is no longer viable and can represent only an impossible legalistic yoke upon an evangelical Christian or pastor. This is the conviction not only of Baptists and other traditionally non-credal denominations, but also of such renowned and conservative theologians as Karl Barth who holds that any human formulation of doctrine (as a creed or confession must be) is only a quest, an approximation, and therefore re1ative.l Are such objections valid? Is the Lutheran church able to justify con- fessional subscription today? And is she able to explain and agree on pre- cisely what is meant by such subscription? Today questions concerning the nature and spirit and extent of conies- sianal subscription have become a vexing problem, an enigma or even an embarrassment to many Lutherans. -

Defining Lutheranism from the Margins: Paul Peter Waldenström on Being a ‘Good Lutheran’ in America Mark Safstrom Augustana College, Rock Island Illinois

Augustana College Augustana Digital Commons Scandinavian Studies: Faculty Scholarship & Scandinavian Studies Creative Works 2012 Defining Lutheranism from the Margins: Paul Peter Waldenström on Being a ‘Good Lutheran’ in America Mark Safstrom Augustana College, Rock Island Illinois Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.augustana.edu/scanfaculty Part of the History of Christianity Commons, Religious Thought, Theology and Philosophy of Religion Commons, and the Scandinavian Studies Commons Augustana Digital Commons Citation Safstrom, Mark. "Defining Lutheranism from the Margins: Paul Peter Waldenström on Being a ‘Good Lutheran’ in America" (2012). Scandinavian Studies: Faculty Scholarship & Creative Works. https://digitalcommons.augustana.edu/scanfaculty/3 This Published Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Scandinavian Studies at Augustana Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Scandinavian Studies: Faculty Scholarship & Creative Works by an authorized administrator of Augustana Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Defining Lutheranism from the Margins: Paul Peter Waldenström on Being a “Good Lutheran” in America MARK SAFSTROM he histories of church institutions may often be written by the orthodox “winners,” but dissenters, protestors, and even her Tetics undoubtedly play important roles in giving direction to the parent institution’s evolving identity. Such voices from the mar- gins often set the agenda at crucial moments, prompting both the dissenters and establishment to engage in a debate to define proper theology and practice. Once a dissenting group has formally sepa- rated from a parent body, there is a risk that teleological hindsight will obscure the nature of these conversations, including the reasons for the ultimate separation and the intentions of both the dissenters and the establishment. -

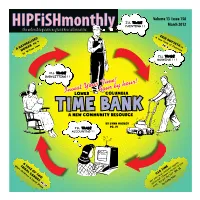

Hour by Hour!

Volume 13 Issue 158 HIPFiSHmonthlyHIPFiSHmonthly March 2012 thethe columbiacolumbia pacificpacific region’sregion’s freefree alternativealternative ERIN HOFSETH A new form of Feminism PG. 4 pg. 8 on A NATURALIZEDWOMAN by William Ham InvestLOWER Your hourTime!COLUMBIA by hour! TIME BANK A NEW community RESOURCE by Lynn Hadley PG. 14 I’LL TRADE ACCOUNTNG ! ! A TALE OF TWO Watt TRIBALChildress CANOES& David Stowe PG. 12 CSA TIME pg. 10 SECOND SATURDAY ARTWALK OPEN MARCH 10. COME IN 10–7 DAILY Showcasing one-of-a-kind vintage finn kimonos. Drop in for styling tips on ware how to incorporate these wearable works-of-art into your wardrobe. A LADIES’ Come See CLOTHING BOUTIQUE What’s Fresh For Spring! In Historic Downtown Astoria @ 1144 COMMERCIAL ST. 503-325-8200 Open Sundays year around 11-4pm finnware.com • 503.325.5720 1116 Commercial St., Astoria Hrs: M-Th 10-5pm/ F 10-5:30pm/Sat 10-5pm Why Suffer? call us today! [ KAREN KAUFMAN • Auto Accidents L.Ac. • Ph.D. •Musculoskeletal • Work Related Injuries pain and strain • Nutritional Evaluations “Stockings and Stripes” by Annette Palmer •Headaches/Allergies • Second Opinions 503.298.8815 •Gynecological Issues [email protected] NUDES DOWNTOWN covered by most insurance • Stress/emotional Issues through April 4 ASTORIA CHIROPRACTIC Original Art • Fine Craft Now Offering Acupuncture Laser Therapy! Dr. Ann Goldeen, D.C. Exceptional Jewelry 503-325-3311 &Traditional OPEN DAILY 2935 Marine Drive • Astoria 1160 Commercial Street Astoria, Oregon Chinese Medicine 503.325.1270 riverseagalleryastoria.com -

The Jacques Barzun Award Lecture

PERNICIOUS AMNESIA: COMBATING THE EPIDEMIC Response to the Conferral of the Inaugural Jacques Barzun Award The American Academy for Liberal Education Washington, D.C. 8 November 1997 Jaroslav Pelikan Sterling Professor Emeritus Yale University The Jacques Barzun Award for Outstanding Contributions to Liberal Education The American Academy for Liberal Education is proud to establish the Jacques Barzun Award, honoring outstanding contributions to liberal education. Named in honor of one of the Academy’s founders, and its honorary chairman, Jacques Barzun, the award recognizes and celebrates qualities of scholarship and leadership in liberal education so perfectly embodied by Dr. Barzun himself. A distinguished scholar, teacher, author, and university administrator (he served for twelve years as Dean of Faculties and Provost of Columbia University), Jacques Barzun is internationally known as one of our most thoughtful commentators on the cultural history of the modern period. Among his most recent books are Critical Questions (a collection of his essays from 1940-1980), A Stroll With William James, and A Word or Two Before You Go. He has reflected on contemporary education in Begin Here: The Forgotten Conditions of Teaching and Learning, Teacher in America, and The American University, How it Runs, Where it is Going. Even a full recounting of Jacques Barzun’s forty or so books and translations, or of his many honors (he is a member of the American Philosophical Society, the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, and a fellow of the Royal Society of Arts) would fail to do full justice to the extent of Barzun’s influence on liberal education in this country. -

Books Added to Benner Library from Estate of Dr. William Foote

Books added to Benner Library from estate of Dr. William Foote # CALL NUMBER TITLE Scribes and scholars : a guide to the transmission of Greek and Latin literature / by L.D. Reynolds and N.G. 1 001.2 R335s, 1991 Wilson. 2 001.2 Se15e Emerson on the scholar / Merton M. Sealts, Jr. 3 001.3 R921f Future without a past : the humanities in a technological society / John Paul Russo. 4 001.30711 G163a Academic instincts / Marjorie Garber. Book of the book : some works & projections about the book & writing / edited by Jerome Rothenberg and 5 002 B644r Steven Clay. 6 002 OL5s Smithsonian book of books / Michael Olmert. 7 002 T361g Great books and book collectors / Alan G. Thomas. 8 002.075 B29g Gentle madness : bibliophiles, bibliomanes, and the eternal passion for books / Nicholas A. Basbanes. 9 002.09 B29p Patience & fortitude : a roving chronicle of book people, book places, and book culture / Nicholas A. Basbanes. Books of the brave : being an account of books and of men in the Spanish Conquest and settlement of the 10 002.098 L552b sixteenth-century New World / Irving A. Leonard ; with a new introduction by Rolena Adorno. 11 020.973 R824f Foundations of library and information science / Richard E. Rubin. 12 021.009 J631h, 1976 History of libraries in the Western World / by Elmer D. Johnson and Michael H. Harris. 13 025.2832 B175d Double fold : libraries and the assault on paper / Nicholson Baker. London booksellers and American customers : transatlantic literary community and the Charleston Library 14 027.2 R196L Society, 1748-1811 / James Raven. -

The Politics of Urban Cultural Policy Global

THE POLITICS OF URBAN CULTURAL POLICY GLOBAL PERSPECTIVES Carl Grodach and Daniel Silver 2012 CONTENTS List of Figures and Tables iv Contributors v Acknowledgements viii INTRODUCTION Urbanizing Cultural Policy 1 Carl Grodach and Daniel Silver Part I URBAN CULTURAL POLICY AS AN OBJECT OF GOVERNANCE 20 1. A Different Class: Politics and Culture in London 21 Kate Oakley 2. Chicago from the Political Machine to the Entertainment Machine 42 Terry Nichols Clark and Daniel Silver 3. Brecht in Bogotá: How Cultural Policy Transformed a Clientist Political Culture 66 Eleonora Pasotti 4. Notes of Discord: Urban Cultural Policy in the Confrontational City 86 Arie Romein and Jan Jacob Trip 5. Cultural Policy and the State of Urban Development in the Capital of South Korea 111 Jong Youl Lee and Chad Anderson Part II REWRITING THE CREATIVE CITY SCRIPT 130 6. Creativity and Urban Regeneration: The Role of La Tohu and the Cirque du Soleil in the Saint-Michel Neighborhood in Montreal 131 Deborah Leslie and Norma Rantisi 7. City Image and the Politics of Music Policy in the “Live Music Capital of the World” 156 Carl Grodach ii 8. “To Have and to Need”: Reorganizing Cultural Policy as Panacea for 176 Berlin’s Urban and Economic Woes Doreen Jakob 9. Urban Cultural Policy, City Size, and Proximity 195 Chris Gibson and Gordon Waitt Part III THE IMPLICATIONS OF URBAN CULTURAL POLICY AGENDAS FOR CREATIVE PRODUCTION 221 10. The New Cultural Economy and its Discontents: Governance Innovation and Policy Disjuncture in Vancouver 222 Tom Hutton and Catherine Murray 11. Creating Urban Spaces for Culture, Heritage, and the Arts in Singapore: Balancing Policy-Led Development and Organic Growth 245 Lily Kong 12.