Insight on How Socio-Economic Minority Student Perceive the Internship Program: a Case Study in South-Eastern of Taiwan Students

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

IAM2019 Summer) Are Pleased to Welcome You to This Meeting Held at Hiroshima, Japan on July 9-12, 2019

ISSN 2218-6387 0 1902 9 772218 638009 IAM International Conference on Innovation and Management Publisher Cheng-Kiang Farn Published By Society for Innovation in Management Editor-in-Chief Executive Secretary Kuang Hui Chiu Ching-Chih Chiang National Taipei University, Taiwan Society for Innovation in Management, Taiwan Editorial Board Cheng-Hsun Ho Ming Kuei Huang National Taipei University, Taiwan Forward-Tech, Taiwan Cheng-Kiang Farn Ramayah Thurasamy National Central University, Taiwan Universiti Sains Malaysia, Malaysia Chi-Feng Tai ReiYao Wu National Chiayi University, Taiwan Shih Hsin University, Taiwan Chih-Chin Liang Shu-Chen Yang National Formosa University, Taiwan National University of Kaohsiung, Taiwan Chun-Der Chen Shu-Hui Lee Ming Chuan University, Taiwan National Taipei University, Taiwan Hsiu-Li Liao Sze-hsun Sylcien Chang Chung Yuan Christian University, Taiwan Da-Yeh University, Taiwan Jessica H.F. Chen Tracy Chang National chi-nan University, Taiwan Chunghwa Telecom, Taiwan Kai Wang Wenchieh Wu National University of Kaohsiung, Taiwan St. John's University, Taiwan Kuangnen Cheng Yao-Chung Yu Marist College, USA National Defense University, Taiwan Li-Ting Huang Zulnaidi Yaacob Chang Gung University, Taiwan Universiti Sains Malaysia, Malaysia Contents Contents Chair’s Message .................................................................................................. 1 Schedule .............................................................................................................. 3 Agenda Session A ..................................................................................................... -

MOU List of KMUTT Partner Universities

MOU List of KMUTT Partner Universities ASIA ASIA ASIA ASIA ASIA Australia India Japan Korea Taiwan B.K Birla Institute of Chia Nan University of Curtin University Of Technology Nippon Institute of Technology Sangmyung university Engineering & Technology Pharmacy and Science Bharati Vidyapeeth Prefectural University of Griffith University Seoul National University Fu Jen Catholic University Deeemed University Hiroshima Swami Ramanand Teerth Shibaura Institute of Lunghwa University of Sci & Macquarie University Marathwada University at Sungkyunkwan University Technology Tech Vishnupuri Royal Melbourne Institute of Indian Institute of Tohoku University Yeojoo Inst. of Tech. Meiho University technology [RMIT] Technology Kanpur National Kaohsiung First University Of New South Wales Indonesia Tokai University Lao University of Science and Technology University of Technology National Pingtung Institute of Universitas Ma Chung Osaka University Department of Agriculture Sydney Commerce U. of Western Sydney Prefectural University of National Taipei University of Brawijaya University National University of Laos Hawkesbury Hiroshima Technology The Science Technology & National Taiwan University of University of Wollongong Bogor Agricultural University Tokyo Institute of Technology Environment Agency Science and Technology Institut Teknologi Bandung Cambodia Tokyo Institute of Technology Malaysia National Tsing Hua University (ITB) Institut Teknologi Sepuluh Royal University of Agriculture Tokyo Metropolitan University University of Malaya National -

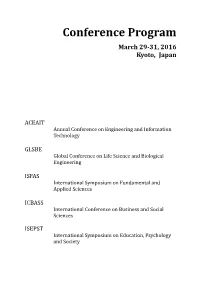

Conference Program

Conference Program March 29-31, 2016 Kyoto, Japan ACEAIT Annual Conference on Engineering and Information Technology GLSBE Global Conference on Life Science and Biological Engineering ISFAS International Symposium on Fundamental and Applied Sciences ICBASS International Conference on Business and Social Sciences ISEPST International Symposium on Education, Psychology and Society ACEAIT Annual Conference on Engineering and Information Technology ISBN 978-986-89298-6-9 GLSBE Global Conference on Life Science and Biological Engineering ISBN 978-986-5654-38-2 ISFAS International Symposium on Fundamental and Applied Sciences ISBN 978-986-89298-5-2 ICBASS International Conference on Business and Social Sciences ISBN 978-986-89298-7-6 ISEPST International Symposium on Education, Psychology and Society ISBN 978-986-89298-8-3 Content General Information for Participants ...................................................................................... 6 International Committees ............................................................................................................ 8 International Committee of ACEAIT ...................................................................................... 8 International Committee of GLSBE ........................................................................................ 9 International Committee of ISFAS ........................................................................................ 10 International Committee of ICBASS .................................................................................... -

A Study on the Development of Advanced Faculty in Leisure and Sport for Higher Education Between 2006 and 2011

A Study on the Development of Advanced Faculty in Leisure and Sport for Higher Education between 2006 and 2011 Cheng-Lung Wu, Department of Marine Sports and Recreation, National Penghu University of Science and Technology, Taiwan Yung-Chuan Tsai, Department of Recreation Sports & Health Promotion, Meiho University, Taiwan Yong Tang, Corresponding Author, Department of Aquatic Sport and Recreation, Taipei College of Maritime Technology, Taiwan ABSTRACT This study employed latent growth curve modeling to verify the growth on the number of full-time faculty in the department relevant to leisure and sports in higher educational institutions in Taiwan. The scope of this study covers the departments relevant to leisure and sport. The number of the full-time faculty in the department relevant to leisure and sport was treated as observed variable for the analysis of its growth. The results found that a goodness fit between the number of students recruited in the latent growth curve model and observed data and that the growth of the number of the faculty in the department relevant to leisure and sport was significantly different along with time and the increase of the number of classes in the department relevant to the leisure and sport. And, the number of the faculty in the department relevant to leisure and sport in between 2006 and 2011 was significantly impacted by the higher educational systems, traditional or vocational universities, both of the number in the beginning point and growth rate were significantly different. It revealed that the factor of traditional and vocational educational system did influence the number of full-time faculty. -

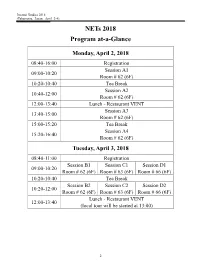

Nets 2018 Program At-A-Glance

Internet Studies 2018 (Takamatsu, Japan, April 2-4) NETs 2018 Program at-a-Glance Monday, April 2, 2018 08:40-16:00 Registration Session A1 09:00-10:20 Room # 62 (6F) 10:20-10:40 Tea Break Session A2 10:40-12:00 Room # 62 (6F) 12:00-13:40 Lunch - Restaurant VENT Session A3 13:40-15:00 Room # 62 (6F) 15:00-15:20 Tea Break Session A4 15:20-16:40 Room # 62 (6F) Tuesday, April 3, 2018 08:40-11:00 Registration Session B1 Session C1 Session D1 09:00-10:20 Room # 62 (6F) Room # 63 (6F) Room # 66 (6F) 10:20-10:40 Tea Break Session B2 Session C2 Session D2 10:20-12:00 Room # 62 (6F) Room # 63 (6F) Room # 66 (6F) Lunch - Restaurant VENT 12:00-13:40 (local tour will be started at 13:00) 2 Internet Studies 2018 (Takamatsu, Japan, April 2-4) Wednesday, April 4, 2018 08:40-11:00 Registration Session E1 Session F1 Session G1 09:00-10:20 Room # 62 (6F) Room # 63 (6F) Room # 66 (6F) 10:20-10:30 Tea Break Session E2 Session F2 Session G2 10:30-12:00 Room # 62 (6F) Room # 63 (6F) Room # 66 (6F) Lunch - Restaurant VENT 12:00-13:40 (local tour will be started at 15:00) 3 Internet Studies 2018 (Takamatsu, Japan, April 2-4) Monday, April 2, 2018 Session A1 9:00-10:20 Room#62(6F) Session Chair: Yu-Chung Hsiao Session Chair: Nangfang College of Sun Yat-Sen University IMPROVING STUDENT ACHIEVEMENT AND SATISFACTION USING VIRTUAL CLASSROOM Apichaya Nimkoompai Thai-Nichi Institute of Technology Pramuk Boonsieng Thai-Nichi Institute of Technology Puwadol Sirikongtham Thai-Nichi Institute of Technology VIDEO WATCH BEHAVIOR ANALYSIS AND APPLICATION IN A OPENEDU MOOCS -

Herbal Supplement Ameliorates Cardiac Hypertrophy in Rats with Ccl4-Induced Liver Cirrhosis

Hindawi Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine Volume 2017, Article ID 5276749, 1 page https://doi.org/10.1155/2017/5276749 Retraction Retracted: Herbal Supplement Ameliorates Cardiac Hypertrophy in Rats with CCl4-Induced Liver Cirrhosis Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine Received 8 August 2017; Accepted 8 August 2017; Published 22 November 2017 Copyright © 2017 Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine has retracted the article titled “Herbal Supplement Amelio- ratesCardiacHypertrophyinRatswithCCl4-Induced Liver Cirrhosis” [1]. The article was found to contain duplicated images in Figure 4(a), in which the IL6 blots are identical to the p-ERK5 blots. The authors provided a corrected figure, with replacements for p-ERK5, which is available as Supplementary Materials. However, they could not provide the underlying blots. References [1] P.-C. Li, Y.-W. Chiu, Y.-M. Lin et al., “Herbal supplement ameliorates cardiac hypertrophy in rats with CCl4-induced liver cirrhosis,” Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine, vol. 2012, Article ID 139045, 9 pages, 2012. Hindawi Publishing Corporation Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine Volume 2012, Article ID 139045, 9 pages doi:10.1155/2012/139045 Research Article -

Student Version Academic and Internship Handbook For

Academic and Internship Handbook for International and Overseas Chinese Students-Student Version 52 Preface Welcome to Taiwan, the Republic of China! Taiwan is blessed with beautiful scenery, a pleasant climate and earnest local people. Our campus has a lively atmosphere, with caring teachers and helpful students. Studying here, not only can you acquire knowledge Welcome to Taiwan ! and expertise in the classroom and participate in diverse extracurricular activities in school, you can also explore the country more thoroughly in your free time, learning Taiwanese culture, tasting local delicacies and visiting famous attractions. On your arrival, you will definitely be thrilled by what you see; the next few years of studying here will, I am sure, leave an unforgettable, beautiful memory in your life. However, local customs, laws and regulations in Taiwan are different from other During your study in Taiwan, in addition to scheduling classroom courses, your countries. To equip you with guidance on schooling and living so that you won’t be at a academic department may arrange internship programs according to relevant regulations, loss in times of trouble, this reference manual has been purposely put together to provide provided they are part of your study, so that you can learn the nature and requirements of information on the problems you may encounter in your studies, internship and daily life, the workplace in your field of study, as well as enabling mutual corroboration of theory as well as their solutions. The information in this manual is for reference only; for matters and practice. Please be aware that the regulations on internship and working part-time not mentioned herein, please consult the designated office in your school. -

8-Hydroxybriaranes from Octocoral Briareum Stechei (Briareidae) (Kükenthal, 1908)

marine drugs Article 8-Hydroxybriaranes from Octocoral Briareum stechei (Briareidae) (Kükenthal, 1908) Thanh-Hao Huynh 1,2, Su-Ying Chien 3, Junichi Tanaka 4 , Zhi-Hong Wen 1,5 , Yang-Chang Wu 6,7, Tung-Ying Wu 8,9,* and Ping-Jyun Sung 1,2,7,10,11,* 1 Department of Marine Biotechnology and Resources, National Sun Yat-sen University, Kaohsiung 804201, Taiwan; [email protected] (T.-H.H.); [email protected] (Z.-H.W.) 2 National Museum of Marine Biology and Aquarium, Pingtung 944401, Taiwan 3 Instrumentation Center, National Taiwan University, Taipei 106319, Taiwan; [email protected] 4 Department of Chemistry, Biology and Marine Science, University of the Ryukyus, Nishihara, Okinawa 9030213, Japan; [email protected] 5 Institute of BioPharmaceutical Sciences, National Sun Yat-sen University, Kaohsiung 804201, Taiwan 6 Graduate Institute of Integrated Medicine, College of Chinese Medicine, China Medical University, Taichung 404333, Taiwan; [email protected] 7 Chinese Medicine Research and Development Center, China Medical University Hospital, Taichung 404394, Taiwan 8 Department of Biological Science & Technology, Meiho University, Pingtung 912009, Taiwan 9 Department of Food Science and Nutrition, Meiho University, Pingtung 912009, Taiwan 10 Graduate Institute of Marine Biology, National Dong Hwa University, Pingtung 944401, Taiwan 11 Graduate Institute of Natural Products, Kaohsiung Medical University, Kaohsiung 807378, Taiwan * Correspondence: [email protected] (T.-Y.W.); [email protected] (P.-J.S.); Tel.: +886-8-779-9821 (ext. 8754) (T.-Y.W.); +886-8-882-5037 (P.-J.S.); Fax: +886-8-779-3281 (T.-Y.W.); +886-8-882-5087 (P.-J.S.) Abstract: Chemical investigation of the octocoral Briareum stechei, collected in the Ie Island, Okinawa, Citation: Huynh, T.-H.; Chien, S.-Y.; Japan, resulted in the isolation of a new briarane-type diterpenoid, briastecholide A (1), as well Tanaka, J.; Wen, Z.-H.; Wu, Y.-C.; Wu, as the previously reported metabolites, solenolide C (2) and briarenolide S (3). -

Associations Between Lifestyle Habits, Perceived Symptoms and Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease in Patients Seeking Health Check-Ups

International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health Article Associations between Lifestyle Habits, Perceived Symptoms and Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease in Patients Seeking Health Check-Ups Chiu-Hua Chang 1,2, Tai-Hsiang Chen 3 , Lan-Lung (Luke) Chiang 3, Chiao-Lin Hsu 4,5,6, Hsien-Chung Yu 4,7,8, Guang-Yuan Mar 9,10 and Chen-Chung Ma 2,* 1 Nursing Department, Kaohsiung Veterans General Hospital, Kaohsiung 813414, Taiwan; [email protected] 2 Department of Healthcare Administration, I-Shou University, Kaohsiung 82445, Taiwan 3 College of Management, Yuan Ze University, Taoyuan 32003, Taiwan; [email protected] (T.-H.C.); [email protected] (L.-L.C.) 4 Health Management Center, Kaohsiung Veterans General Hospital, Kaohsiung 813414, Taiwan; [email protected] (C.-L.H.); [email protected] (H.-C.Y.) 5 Center for Geriatrics and Gerontology, Kaohsiung Veterans General Hospital, Kaohsiung 813414, Taiwan 6 Department of Nursing, Meiho University, Pingtung 912009, Taiwan 7 Department of Business Management, National Sun Yat-sen University, Kaohsiung 80424, Taiwan 8 Division of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Department of Internal Medicine, Kaohsiung Veterans General Hospital, Kaohsiung 813414, Taiwan 9 Graduate Institute of Health Care, Meiho University, Pingtung 912009, Taiwan; [email protected] 10 Kaohsiung Municipal United Hospital, Kaohsiung 80457, Taiwan * Correspondence: [email protected] Citation: Chang, C.-H.; Chen, T.-H.; Chiang, L.-L.; Hsu, C.-L.; Yu, H.-C.; Abstract: Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) is one of the most common diseases. It mainly Mar, G.-Y.; Ma, C.-C. Associations between Lifestyle Habits, Perceived causes the stomach contents to flow back to the esophagus, thereby stimulating the esophagus Symptoms and Gastroesophageal and causing discomfort. -

Poster Sessions (1)

Conference Program July 16-18, 2019 Hokkaido, Japan ASMSS Annual Symposium on Management and Social Sciences GCEAS Global Conference on Engineering and Applied Science ACCMES Asian Conference on Civil, Material and Environmental Sciences ICEPS International Conference on Education, Psychology and Social Studies ASMSS Annual Symposium on Management and Social Sciences ISBN: 978-986-90263-7-6 GCEAS Global Conference on Engineering and Applied Science ISBN 978-986-5654-24-5 ACCMES Asian Conference on Civil, Material and Environmental Sciences ISBN 978-986-89298-0-7 ICEPS International Conference on Education, Psychology and Social Studies ISBN: 978-986-5654-26-9 Content Welcome Message ........................................................................................................................... 3 General Information for Participants ...................................................................................... 5 International Committees of Natural Sciences ...................................................................... 7 International Committees of Social Sciences ...................................................................... 10 Special Thanks to Session Chairs ............................................................................................ 13 Conference Venue Information ................................................................................................ 14 Floor Plan ...................................................................................................................................... -

The Effect of Tertiary Education Expansion on Fertility: a Note on Identification

DISCUSSION PAPER SERIES IZA DP No. 14672 ‘Bachelors’ and Babies: The Effect of Tertiary Education Expansion on Fertility Tushar Bharati Simon Chang Qing Li AUGUST 2021 DISCUSSION PAPER SERIES IZA DP No. 14672 ‘Bachelors’ and Babies: The Effect of Tertiary Education Expansion on Fertility Tushar Bharati Qing Li University of Western Australia Business Shanghai University School Simon Chang University of Western Australia Business School and IZA AUGUST 2021 Any opinions expressed in this paper are those of the author(s) and not those of IZA. Research published in this series may include views on policy, but IZA takes no institutional policy positions. The IZA research network is committed to the IZA Guiding Principles of Research Integrity. The IZA Institute of Labor Economics is an independent economic research institute that conducts research in labor economics and offers evidence-based policy advice on labor market issues. Supported by the Deutsche Post Foundation, IZA runs the world’s largest network of economists, whose research aims to provide answers to the global labor market challenges of our time. Our key objective is to build bridges between academic research, policymakers and society. IZA Discussion Papers often represent preliminary work and are circulated to encourage discussion. Citation of such a paper should account for its provisional character. A revised version may be available directly from the author. ISSN: 2365-9793 IZA – Institute of Labor Economics Schaumburg-Lippe-Straße 5–9 Phone: +49-228-3894-0 53113 Bonn, Germany -

201608 Tokyo Conference Program

Conference Program Okinawa, Japan July, 2015 APICENS Asia-Pacific International Congress on Engineering & Natural Sciences ISCEAS International Scientific Conference on Engineering and Applied Sciences IACSSM International Academic Conference on Social Sciences and Management ICEPS International Conference on Education, Psychology and Society APICENS Asia-Pacific International Congress on Engineering & Natural Sciences ISBN: 978-986-89298-2-1 ISCEAS International Scientific Conference on Engineering and Applied Sciences ISBN: 978-986-89844-9-3 IACSSM International Academic Conference on Social Sciences and Management ISBN: 978-986-5654-23-8 ICEPS International Conference on Education, Psychology and Society ISBN: 978-986-5654-26-9 Content General Information for Conference Participants ................................................................ 3 Conference Venue Information ................................................................................................... 5 Lunch Venue Information .............................................................................................................. 6 Conference Schedule ....................................................................................................................... 8 Conference Organization ............................................................................................................. 12 APICENS International Committee Board ..................................................................... 12 ISCEAS International Committee Board........................................................................