The Effect of Tertiary Education Expansion on Fertility: a Note on Identification

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Taiwan Fulbright Grantees 2019-2020

Taiwan Grantees 2019-2020 Senior Research Grants: 19 Fulbright-Formosa Plastics Group Scholarship, for Senior Scholar: 2 Experience America Research Grants: 1 Doctoral Dissertation Research Grants: 3 Graduate Study Grants: 4 Non-Academic Professionals Grants: 7 DA: 1 FLTA: 22 ___________________________________ Total: 59 Grantee Field/ Project/ Host I. Senior Research Grants 1 Chang, Yung-Hsiang (張詠翔) Linguistics Associate Professor Department of English Using Ultrasound in Articulation Therapy National Taipei University of Technology with Mandarin-Speaking Children Haskins Laboratories, CT 2 Chen, Hung-Kun (陳鴻崑) Accounting/Finance Associate Professor Department of Banking and Finance Study on Share Pledging and Executives Tamkang University Compensation University of Southern California, CA 3 Chen, Shyh-Jer (陳世哲) Business Distinguished Professor Institute of Human Resource Management, The Effect Of Family Values On High College of Management Commitment Work System And Work Quality National Sun Yat-sen University University of Washington, WA 4 Cheng, Ya-Wei (鄭雅薇) Neuroscience Professor Institute of Neuroscience How Exercise Helps Anxiety: from Cognitive National Yang-Ming University Neuroscience to Multimodal Neuroimaging University of North Carolina, Greensboro, NC - 1 - Grantee Field/ Project/ Host 5 Chiou, Yi-Hung (邱奕宏) International Relations Associate Professor Center of General Education/ Research Destined to Conflict? The Impacts of US- Office for Global Political Economy China Strategic Competition on the Global National Chiao -

Separation Enhancement of Mechanical Filters by Adding Negative Air Ions

132 Journal of Membrane and Separation Technology, 2016, 5, 132-139 Separation Enhancement of Mechanical Filters by Adding Negative Air Ions Shinhao Yang1, Yi-Chin Huang1, Chin-Hsiang Luo2,* and Chi-Yu Chuang3 1Center for General Education, Toko University, Chiayi 61363, Taiwan 2Department of Safety, Health and Environmental Engineering, Hungkuang University, Taichung 43302, Taiwan 3Department of Occupational Safety and Health, Chang Jung Christian University, Tainan 71101, Taiwan Abstract: The purpose of this work is to combine negative air ions (NAIs) and mechanical filters for removal of indoor suspended particulates. Various factors, including aerosol size (0.05-0.45 µm), face velocity (10 and 20 cm/s), species of aerosol (potassium chloride and dioctyl phthalate), relative humidity (30% and 70%), and concentrations of NAIs (2 × 104, 1 × 105, and 2 × 105 NAIs/cm3) were considered to evaluate their effects on the aerosol collection characteristics of filters. Results show that the aerosol penetration through the mechanical filter is higher than that through the mechanical filters cooperated with NAIs. This finding implies that the aerosol removal efficiency of mechanical filters can be improved by NAIs. Furthermore, the aerosol penetration through the mechanical filters increased with the aerosol size when NAIs were added. That is due to that the aerosol is easier to be charged when its size gets larger. The results also indicate the aerosol penetration decreased with the NAIs concentration increased. Reversely, aerosol penetration through the mechanical filters increased with the face velocity under the influence of NAIs. The aerosol penetration through the filter with NAIs was no affected with relative humidity. -

Study in Taiwan

1 2 NORTH 3 1 Taipei Keelung Where is 2 Taiwan? 4 3 Taoyuan 5 4 Hsinchu 6 5 Yilan 7 Welcome to MIDDLE our friendly island paradise 6 Miaoli 8 7 Taichung Taiwan is a modern, free, and democratic society 15 where people are hardworking, fun-loving, 10 8 Changhua educated and friendly. Whatever your field of 9 9 Yunlin 10 Nantou interest, we think you will find studying in Taiwan 11 richly rewarding. We welcome you and hope you 11 Chayi enjoy learning and adventure in Taiwan. 12 SOUTH 13 16 12 Tainan 13 Kaohsiung Taiwan 14 Pingtung 14 EAST Getting to know 15 Hualien 16 Taitung 1 U | Undergraduate G | Graduate I | Internship | Over 90% Taught in English | 75%~89% Taught in English | 50%~74% Taught in English | Under 50% Taught in English | Taught in Chinese | Other Humanities & Social Science National Chengchi University Taipei National Taiwan University Taipei U G NCCU International Summer School (ISS) U G Summer+ Programs: +1 Summer Intensive Program for Chinese and Culture The NCCU International Summer School (ISS) will give you a pretty comprehensive view of Taiwan in the NTU’s summer+ “Plus One” program combines NTU Chinese Language program with thought- global context, and its close connection to Asia-Pacific culture and economy. The NCCU ISS will enable provoking Exploring Taiwan academic courses taught by experienced university professors. This July 30th ~ you to: combination is especially designed for international students who wish to master Chinese language August 24th 2012 July 2nd ~ while also gaining a deeper understanding of Taiwan’s geography, society, and culture heritages. -

Conference Program

ICMHI 2017 International Conference on Medical and Health Informatics Table of Contents Welcome Address -------------------------------------------------------------- 2 Conference Committee ------------------------------------------------------- 3 Conference Information ----------------------------------------------------- 5 Presentation Instructions --------------------------------------------------- 6 Invited Speakers Introduction --------------------------------------------- 7 Brief Schedule --------------------------------------------------------------- 17 Venue Floor Plan ------------------------------------------------------------ 19 Detail Schedule --------------------------------------------------------------- 20 Student Essay Competition Session ------------------------------------ 20 Session I: Computational Intelligence Methodologies--------------- 29 Session II: Biomedical Data mining ----------------------------------- 35 Session III: Health Information System ------------------------------- 40 Session VI: Health Risk Evaluation ------------------------------------ 45 Session V: Healthcare Quality Management -------------------------- 50 Session VI: Medical Image Processing & Game --------------------- 55 Listeners ----------------------------------------------------------------------- 69 Post Conference One Day Visit ------------------------------------------- 70 Author Index ----------------------------------------------------------------- 71 Feedback ---------------------------------------------------------------------- -

Applying the Membrane-Less Electrolyzed Water Spraying for Inactivating Bioaerosols

Aerosol and Air Quality Research, 13: 350–359, 2013 Copyright © Taiwan Association for Aerosol Research ISSN: 1680-8584 print / 2071-1409 online doi: 10.4209/aaqr.2012.05.0124 Applying the Membrane-Less Electrolyzed Water Spraying for Inactivating Bioaerosols Chi-Yu Chuang1, Shinhao Yang2*, Hsiao-Chien Huang2, Chin-Hsiang Luo3, Wei Fang1, Po-Chen Hung4, Pei-Ru Chung5 1 Department of Bio-Industrial Mechatronics Engineering, National Taiwan University, Taipei 10617, Taiwan 2 Center for General Education, Toko University, Chiayi 61363, Taiwan 3 Department of Safety, Health and Environmental Engineering, Hungkuang University, Taichung 43302, Taiwan 4 Institute of Occupational Safety and Health, Council of Labor Affairs, Taipei 10346, Taiwan 5 Union Safety Environment Technology Co., Ltd, Taipei 10458, Taiwan ABSTRACT The inactivating efficiency using membrane-less electrolyzed water (MLEW) spraying was evaluated against two airborne strains, Staphylococcus aureus and λ virus aerosols, in an indoor environment-simulated chamber. The air exchanged rate (ACH) of the chamber was controlled at 0.5 and 1.0 h–1. MLEW with a free available chlorine (FAC) concentrations of 50 and 100 ppm were pumped and sprayed into the chamber to treat microbial pre-contaminated air. Bioaerosols were collected and cultured from air before and after MLEW treatment. The first-order constant inactivation efficiency of the initial counts of 3 × 104 colony-forming units (CFU or PFU)/m3 for both microbial strains were observed. A higher FAC concentration of MLEW spraying resulted in greater inactivation efficiency. The inactivation coefficient under ACH 1.0 h–1 was 0.481 and 0.554 (min–1) for Staphylococcus aureus of FAC 50 and 100 ppm spraying. -

Smart Home Power Management Based on Internet of Things and Smart Sensor Networks

Sensors and Materials, Vol. 33, No. 5 (2021) 1687–1702 1687 MYU Tokyo S & M 2564 Smart Home Power Management Based on Internet of Things and Smart Sensor Networks Tzer-Long Chen,1 Tsan-Ching Kang,2 Chien-Yun Chang,3 Tsung-Chih Hsiao,4,5* and Chih-Cheng Chen,6,7** 1Department of Finance, Providence University, Taichung 43301, Taiwan 2College of Computing and Informatics, Providence University, Taichung 43301, Taiwan 3Department of Fashion Business and Merchandising, Ling Tung University, Taichung 40852, Taiwan 4College of Computer Science and Technology, Huaqiao University, Xiamen, Fujian 361021, China 5Xiamen Key Laboratory of Data Security and Blockchain Technology, Huaqiao University, Xiamen, Fujian 361021, China 6Department of Automatic Control Engineering, Feng Chia University, Taichung 40724, Taiwan 7Department of Aeronautical Engineering, Chaoyang University of Technology, Taichung 413310, Taiwan (Received October 21, 2020; accepted March 8, 2021) Keywords: smart home, Internet of Things, smartphone, app implementation, sensor networks We have developed a system that includes a newly designed smart socket for IoT sensors and a cloud platform for smart home power management. The system can initiate the platform service upon the user’s authentication and give suggestions based on the analysis of usage patterns. By sending data to the analysis system through the IoT, the system can recommend to the user the most suitable power management setting, calculate the power consumption requirement of the user, and determine whether it is within a reasonable range. The cloud platform employs a mobile device app, which adopts a graphical user interface. The app effectively provides users with information on their domestic power consumption. -

The Organizational Commitment, Personality Traits and Teaching Efficacy of Junior High School Teachers: the Meditating Effect of Job Involvement

The Organizational Commitment, Personality Traits and Teaching Efficacy of Junior High School Teachers: The Meditating Effect of Job Involvement Dr. Hsingkuang Chi, Nanhua University, Taiwan Dr. Hueryren Yeh, Shih Chien University, Kaohsiung Campus, Taiwan Shu-min Choum, Yuanchang Junior High School Yunlin County & Nanhua University, Taiwan ABSTRACT The purpose of the research was to explore the relationship between job involvement, personality traits, organizational commitment and teaching efficacy. In addition, the study examined the mediating effect of job involvement on organizational commitment and teaching efficacy among junior high school teachers in Yunlin County, Taiwan. The study also investigated the moderating effects of personality traits on job involvement and teaching efficacy. The questionnaire was used as the main instrument to collect data. 349 junior high school teachers in Yunlin County, Taiwan expressed their willingness to participate in the study through the telephone inquiry. The numbers of valid questionnaires were 290. The effective response rate was 83.1%. The findings of the research were summarized as follows:(1) Job involvement has a significant and positive influence on teaching efficacy; (2) personality traits have a significant and positive influence on teaching efficacy; (3) organizational commitment has a significant and positive influence on job involvement; (4) organizational commitment has a significant and positive influence on teaching efficacy; (5) job involvement has a meditating effect between organizational commitment and teaching efficacy; (6) personality traits have no moderation effect between job involvement and teaching efficacy. Keywords: Job Involvement, Personality Traits, Organizational Commitment, Teaching Efficacy, Mediating Effect, Moderating Effect INTRODUCTION A teaching job is not as easy as people think, even in teaching, administration and consultation. -

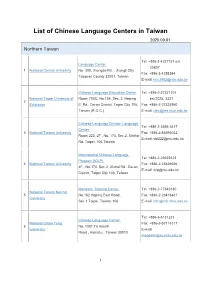

List of Chinese Language Centers in Taiwan 2020.09.01

List of Chinese Language Centers in Taiwan 2020.09.01 Northern Taiwan Tel: +886-3-4227151 ext. Language Center 33807 1 National Central University No. 300, Jhongda Rd. , Jhongli City , Fax: +886-3-4255384 Taoyuan County 32001, Taiwan E-mail: [email protected] Chinese Language Education Center Tel: +886-2-27321104 National Taipei University of Room 700C, No.134, Sec. 2, Heping ext.2025, 3331 2 Education E. Rd., Da-an District, Taipei City 106, Fax: +886-2-27325950 Taiwan (R.O.C.) E-mail: [email protected] Chinese Language Division Language Tel: +886-2-3366-3417 Center 3 National Taiwan University Fax: +886-2-83695042 Room 222, 2F , No. 170, Sec.2, XinHai E-mail: [email protected] Rd, Taipei, 106,Taiwan International Chinese Language Tel: +886-2-23639123 Program (ICLP) 4 National Taiwan University Fax: +886-2-23626926 4F., No.170, Sec.2, Xinhai Rd., Da-an E-mail: [email protected] District, Taipei City 106, Taiwan Mandarin Training Center Tel: +886-2-77345130 National Taiwan Normal 5 No.162 Hoping East Road , Fax: +886-2-23418431 University Sec.1 Taipei, Taiwan 106 E-mail: [email protected] Tel: +886-3-5131231 Chinese Language Center National Chiao Tung Fax: +886-3-57114317 6 No. 1001 Ta Hsueh University E-mail: Road , Hsinchu , Taiwan 30010 [email protected] 1 Chinese Language Center Tel: +886-2-2938-7141/7142 No.64, Sec. 2, Zhinan Rd., Wenshan Fax: +886-2-2939-6353 7 National Chengchi University District E-mail: Taipei City 11605, Taiwan (R.O.C.) [email protected] Tel: +886-2-2700-5858 Mandarin Learning Center ext.8131~8136 8 Chinese Culture University 4F , No.231, Sec.2, Chien-Kuo S. -

Study in Taiwan - 7% Rich and Colorful Culture - 15% in Taiwan, Ancient Chinese Culture Is Uniquely Interwoven No.7 in the Fabric of Modern Society

Le ar ni ng pl us a d v e n t u r e Study in Foundation for International Cooperation in Higher Education of Taiwan (FICHET) Address: Room 202, No.5, Lane 199, Kinghua Street, Taipei City, Taiwan 10650, R.O.C. Taiwan Website: www.fichet.org.tw Tel: +886-2-23222280 Fax: +886-2-23222528 Ministry of Education, R.O.C. Address: No.5, ZhongShan South Road, Taipei, Taiwan 10051, R.O.C. Website: www.edu.tw www.studyintaiwan.org S t u d y n i T a i w a n FICHET: Your all – inclusive information source for studying in Taiwan FICHET (The Foundation for International Cooperation in Higher Education of Taiwan) is a Non-Profit Organization founded in 2005. It currently has 114 member universities. Tel: +886-2-23222280 Fax: +886-2-23222528 E-mail: [email protected] www.fichet.org.tw 加工:封面全面上霧P 局部上亮光 Why Taiwan? International Students’ Perspectives / Reasons Why Taiwan?1 Why Taiwan? Taiwan has an outstanding higher education system that provides opportunities for international students to study a wide variety of subjects, ranging from Chinese language and history to tropical agriculture and forestry, genetic engineering, business, semi-conductors and more. Chinese culture holds education and scholarship in high regard, and nowhere is this truer than in Taiwan. In Taiwan you will experience a vibrant, modern society rooted in one of world’s most venerable cultures, and populated by some of the most friendly and hospitable people on the planet. A great education can lead to a great future. What are you waiting for? Come to Taiwan and fulfill your dreams. -

IAM2019 Summer) Are Pleased to Welcome You to This Meeting Held at Hiroshima, Japan on July 9-12, 2019

ISSN 2218-6387 0 1902 9 772218 638009 IAM International Conference on Innovation and Management Publisher Cheng-Kiang Farn Published By Society for Innovation in Management Editor-in-Chief Executive Secretary Kuang Hui Chiu Ching-Chih Chiang National Taipei University, Taiwan Society for Innovation in Management, Taiwan Editorial Board Cheng-Hsun Ho Ming Kuei Huang National Taipei University, Taiwan Forward-Tech, Taiwan Cheng-Kiang Farn Ramayah Thurasamy National Central University, Taiwan Universiti Sains Malaysia, Malaysia Chi-Feng Tai ReiYao Wu National Chiayi University, Taiwan Shih Hsin University, Taiwan Chih-Chin Liang Shu-Chen Yang National Formosa University, Taiwan National University of Kaohsiung, Taiwan Chun-Der Chen Shu-Hui Lee Ming Chuan University, Taiwan National Taipei University, Taiwan Hsiu-Li Liao Sze-hsun Sylcien Chang Chung Yuan Christian University, Taiwan Da-Yeh University, Taiwan Jessica H.F. Chen Tracy Chang National chi-nan University, Taiwan Chunghwa Telecom, Taiwan Kai Wang Wenchieh Wu National University of Kaohsiung, Taiwan St. John's University, Taiwan Kuangnen Cheng Yao-Chung Yu Marist College, USA National Defense University, Taiwan Li-Ting Huang Zulnaidi Yaacob Chang Gung University, Taiwan Universiti Sains Malaysia, Malaysia Contents Contents Chair’s Message .................................................................................................. 1 Schedule .............................................................................................................. 3 Agenda Session A ..................................................................................................... -

Supplementary Information

SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION Astragalus polysaccharides (PG2) enhances the M1 polarization of macrophages, functional maturation of dendritic cells, and T cell-mediated anticancer immune responses in patients with lung cancer Oluwaseun Adebayo Bamodu a,b# , Kuang-Tai Kuo c,d# , Chun-Hua Wang e,f , Wen-Chien Huang g,h , Alexander T.H. Wu i, Jo-Ting Tsai j,k , Kang-Yun Lee l, Chi-Tai Yeh c,d,m* and Liang-Shun Wang a,b * a Division of Hematology & Oncology, Department of Medicine, Shuang Ho Hospital, Taipei Medical University, New Taipei City, Taiwan. b Department of Medical Research and Education, Shuang Ho Hospital, Taipei Medical University, New Taipei City, Taiwan. c Division of Thoracic Surgery, Department of Surgery, Shuang Ho Hospital, Taipei Medical University, New Taipei City, Taiwan. d Division of Thoracic Surgery, Department of Surgery, School of Medicine, College of Medicine, Taipei Medical University, Taipei, Taiwan. e Department of Dermatology, Taipei Tzu Chi Hospital, Buddhist Tzu Chi Medical Foundation, New Taipei City, Taiwan. f School of Medicine, Buddhist Tzu Chi University, Hualien, Taiwan g MacKay Medical College, Taipei, Taiwan. h Division of Thoracic Surgery, Department of Surgery, MacKay Memorial Hospital, Taipei, Taiwan. i The Ph.D. Program for Translational Medicine, College of Medical Science and Technology, Taipei Medical University, Taipei, Taiwan j Department of Radiation Oncology, Shuang Ho Hospital, Taipei Medical University, New Taipei City, Taiwan. k Department of Radiology, School of Medicine, College of Medicine, Taipei Medical University, Taipei, Taiwan. l Division of Pulmonary Medicine, Department of Internal Medicine, Shuang Ho Hospital, Taipei Medical University, Taiwan. m Department of Biotechnology and Pharmaceutical Technology, Yuanpei University of Medical Technology, Hsinchu City 30015, Taiwan # These authors contributed equally to this work. -

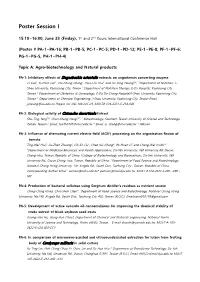

Poster Session I

Poster Session I 15:10~16:00, June 23 (Friday), 1st and 2nd floors International Conference Hall (Poster # PA-1~PA-16; PB-1~PB-5; PC-1~PC-5; PD-1~PD-12; PE-1~PE-8; PF-1~PF-6; PG-1~PG-5, PH-1~PH-4) Topic A: Agro-biotechnology and Natural products PA-1: Inhibitory effects of Siegesbeckia orientalis extracts on angiotensin converting enzyme Ci Luo1, Yi-Chen Lee2, Chi-Chang Chang3, Hsia-Fen Hsu1 and Jer-Yiing Houng1,4,, 1Department of Nutrition, I- Shou University, Kaohsiung City, Taiwan 2 Department of Nutrition Therapy, E-Da Hospital, Kaohsiung City, Taiwa n 3 Department of Obstetrics & Gynecology, E-Da Da-Chang Hospital/I-Shou University, Kaohsiung City, Taiwa n 4 Department of Chemical Engineering, I-Shou University, Kaohsiung City, Taiwan Email: [email protected] Project no: ISU-104-IUC-01, MOST# 104-2221-E-214-046 PA-2: Biological activity of Cistanche deserticola Extract Shu-Ting Yang1,2, Chun-Sheng Hang1,3*, 1 Biotechnology, Southern Taiwan University of Science and Technology, Tainan, Taiwan 2 Email: [email protected] * Email: [email protected] * Advisor PA-3: Influence of alternating current electric field (ACEF) processing on the organization fission of tomato Ting-Wei Hsu1, Jia-Zhen Zhuang1, Chi-En Liu1, Chao Kai Chang2, Po-Hsien Li1 and Chang-Wei Hsieh3* 1Department of Medicinal Botanicals and Health Applications, Da-Yeh University, 168 University Rd, Dacun, Chang-Hua, Taiwan, Republic of China. 2College of Biotechnology and Bioresources, Da-Yeh University, 168 University Rd., Dacun,Chang-Hua, Taiwan, Republic of China.