For Peer Review Only Journal: BMJ Open

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Review of Anticoagulant Drugs in Paediatric Thromboembolic Disease

18th Expert Committee on the Selection and Use of Essential Medicines (21 to 25 March 2011) Section 12: Cardiovascular medicines 12.5 Antithrombotic medicines Review of Anticoagulant Drugs in Paediatric Thromboembolic Disease September 2010 Prepared by: Fiona Newall Anticoagulation Nurse Manager/ Senior Research Fellow Royal Children’s Hospital/ The University of Melbourne Melbourne, Australia 1 Contents Intent of Review Review of indications for antithrombotic therapy in children Venous thromboembolism Arterial thrombeombolism Anticoagulant Drugs Unfractionated heparin Mechanism of action and pharmacology Dosing and administration Monitoring Adverse events Formulary Summary recommendations Vitamin K antagonists Mechanism of action and pharmacology Dosing and administration Monitoring Adverse events Formulary Summary recommendations Low Molecular Weight Heparins Mechanism of action and pharmacology Dosing and administration Monitoring Adverse events Formulary Summary recommendations ??Novel anticoagulants Summary 2 1. Intent of Review To review the indications for anticoagulant therapies in children. To review the epidemiology of thromboembolic events in children. To review the literature and collate the evidence regarding dosing, administration and monitoring of anticoagulant therapies in childhood. To review the safety of anticoagulant therapies and supervision required To give recommendations for the inclusion of anticoagulants on the WHO Essential Medicines List 2. Review of indications for antithrombotic therapy in children Anticoagulant therapies are given for the prevention or treatment of venous and/or arterial thrombosis. The process of ‘development haemostasis’, whereby the proteins involved in coagulation change quantitatively and qualitatively with age across childhood, essentially protects children against thrombosis(1-5). For this reason, insults such as immobilization are unlikely to trigger the development of thrombotic diseases in children. -

Pharmacokinetics of Anticoagulant Rodenticides in Target and Non-Target Organisms Katherine Horak U.S

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln USDA National Wildlife Research Center - Staff U.S. Department of Agriculture: Animal and Plant Publications Health Inspection Service 2018 Pharmacokinetics of Anticoagulant Rodenticides in Target and Non-target Organisms Katherine Horak U.S. Department of Agriculture, [email protected] Penny M. Fisher Landcare Research Brian M. Hopkins Landcare Research Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/icwdm_usdanwrc Part of the Life Sciences Commons Horak, Katherine; Fisher, Penny M.; and Hopkins, Brian M., "Pharmacokinetics of Anticoagulant Rodenticides in Target and Non- target Organisms" (2018). USDA National Wildlife Research Center - Staff Publications. 2091. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/icwdm_usdanwrc/2091 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the U.S. Department of Agriculture: Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in USDA National Wildlife Research Center - Staff ubP lications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Chapter 4 Pharmacokinetics of Anticoagulant Rodenticides in Target and Non-target Organisms Katherine E. Horak, Penny M. Fisher, and Brian Hopkins 1 Introduction The concentration of a compound at the site of action is a determinant of its toxicity. This principle is affected by a variety of factors including the chemical properties of the compound (pKa, lipophilicity, molecular size), receptor binding affinity, route of exposure, and physiological properties of the organism. Many compounds have to undergo chemical changes, biotransformation, into more toxic or less toxic forms. Because of all of these variables, predicting toxic effects and performing risk assess- ments of compounds based solely on dose are less accurate than those that include data on absorption, distribution, metabolism (biotransformation), and excretion of the compound. -

Heavy Rainfall Provokes Anticoagulant Rodenticides' Release from Baited

Journal Pre-proof Heavy rainfall provokes anticoagulant rodenticides’ release from baited sewer systems and outdoor surfaces into receiving streams Julia Regnery1,*, Robert S. Schulz1, Pia Parrhysius1, Julia Bachtin1, Marvin Brinke1, Sabine Schäfer1, Georg Reifferscheid1, Anton Friesen2 1 Department of Biochemistry, Ecotoxicology, Federal Institute of Hydrology, 56068 Koblenz, Germany 2 Section IV 1.2 Biocides, German Environment Agency, 06813 Dessau-Rosslau, Germany *Corresponding author. Email: [email protected] (J. Regnery); phone: +49 261 1306 5987 Journal Pre-proof A manuscript prepared for possible publication in: Science of the Total Environment May 2020 1 Journal Pre-proof Abstract Prevalent findings of anticoagulant rodenticide (AR) residues in liver tissue of freshwater fish recently emphasized the existence of aquatic exposure pathways. Thus, a comprehensive wastewater treatment plant and surface water monitoring campaign was conducted at two urban catchments in Germany in 2018 and 2019 to investigate potential emission sources of ARs into the aquatic environment. Over several months, the occurrence and fate of all eight ARs authorized in the European Union as well as two pharmaceutical anticoagulants was monitored in a variety of aqueous, solid, and biological environmental matrices during and after widespread sewer baiting with AR-containing bait. As a result, sewer baiting in combined sewer systems, besides outdoor rodent control at the surface, was identified as a substantial contributor of these biocidal active ingredients in the aquatic environment. In conjunction with heavy or prolonged precipitation during bait application in combined sewer systems, a direct link between sewer baiting and AR residues in wastewater treatment plant influent, effluent, and the liver of freshwater fish was established. -

Some Aspects of the Pharmacology of Oral Anticoagulants

Some aspects of the pharmacology of oral anticoagulants The pharmacology of oral anticoagulants ls discussed with particular rejerence to data of value in the management of therapy. The importance of individual variability in response and drug interaction is stressed. Other effects of these agents which may have clinical utility are noted. William W. Coon, M.D., and Park W. Willis 111, M.D., Ann Arbor, Mich. The Departments of Surgery (Section of General Surgery) and Medicine, University of Michigan Medical School In the twenty-five years sinee the isola dividual struetural features but by a com tion of the hemorrhagie faetor in spoiled bination of several: molecular shape, in sweet clever," the gradually inereasing creased aetivity with 6 membered hetero utilization of oral antieoagulants for the eyclic rings with a substituent in position prevention and therapy of thromboembolie 8 and with a methoxyl rather than a free disease has made them one of the most hydroxl group. Also important is the dernon widely used groups of pharmacologic stration that levorotatory warfarin is seven agents. This review is restrieted to as times more aetive than its enantiomer.F" peets of the pharmaeology of these agents As Hunter and Shepherd'" have pointed whieh may be important to their proper out, the failure to obtain a precise cor clinieal utilization. relation between strueture and antieoagu lant aetivity is "not surprising in view of Relation of structure to function the influence of small struetural changes The oral antieoagulants have been di on sueh variables as solubility, rate of ab vided into four main groups on the basis sorption, ease of distribution, degree of of ehemieal strueture (Fig. -

Comparing Antithrombotic Strategies After Bioprosthetic

Antithrombotic Strategies after bAVR Evidence-based Synthesis Program APPENDIX A. SEARCH STRATEGIES DATABASES/WEBSITES: Ovid Medline 1946 to June 19, 2017 PubMed (non-Medline materials) January 9, 2017 Elsevier EMBASE February 1, 2017 EBM Reviews (CDSR, DARE, HTA, Cochrane CENTRAL, etc.) January 24, 2017 Clinicaltrials.gov January 24, 2017 RoPR (Registry of Patient Registries January 24, 2017 SEARCH STRATEGIES Updated search strategy – 9Jan2017, after adding “placement” based on Stevenson editorial: Epub Ahead of Print, In-Process & Other Non-Indexed Citations, Ovid MEDLINE(R) Daily and Ovid MEDLINE(R) 1946 to Present Date Searched: January 9, 2017 Searched by: Robin Paynter, MLIS 1 Heart Valve Prosthesis/ or Heart Valve Prosthesis Implantation/ or Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement/ or 80730 (((aort* or valve*) adj3 (implant* or replac* or graft*)) or AVR or AVRs or mini-AVR* or "surgical AVR*" or SAVR or SAVRs or "bioprosthe* AVR*" or "bio-prosthe* AVR*" or "biologic* AVR*" or bAVR* or TAVI* or TAVR* or PAVR* or ((transcatheter* or trans-catheter* or transfemoral* or trans-femoral* or transapical* or trans-apical* or transaxillar* or trans-axillar* or transvascular* or trans-vascular* or percutaneous* or bioprosthet* or bio-prosthet* or biologic*) adj3 (implant* or placement* or replac* or graft*))).tw,kf. 2 aortic valve/ or (aort* or answer or "Anticoagulation Treatment Influence on Postoperative Patients" or 998641 action).tw,kf. 3 bioprosthesis/ or (bioprosthe* or bio-prosthe* or ((biologic* or tissue* or prosthe*) adj3 (aort* or valv* or graft*)) or 512785 bovine* or porcine* or equine* or xenograft* or xenogen* or heterograft* or xenobioprosthe* or 3F* or ACURATE- TA* or Biocor* or Carpentier-Edwards* or COLIBRI* or CoreValve* or Crown PRT* or DOKIMOS* or Engager* or EPIC* or Freestyle* or FS or HANCOCK* or INSPIRIS* or J-Valve* or JENAVALVE* or MITROFLOW* or MOSAIC* or MYVAL* or Perceval* or Perimount* or Sapien* or SOLO or TLPB* or TRIFECTA*).tw,kf. -

Risk of Bleeding with Non-Vitamin K Oral Antagonists and Phenprocoumon in Routine Care Patients with Non-Valvular Atrial Fibrill

Risk of bleeding with non-vitamin K oral antagonists and phenprocoumon in routine care patients with non-valvular atrial fibrillation Poster-Nr 2608 S.H. Hohnloser1, M. Näbauer2, A. Genet3, T. Windeck3, F. Volz3 ,G. Hack4, C. Lefevre5, S. Dheban6, J. Jacob6, L. Hickstein6 , F. Leverkus3 1J. W. Goethe University, Dep. Of Cardiology, Frankfurt, Germany, 2Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität, Munich, Germany, 3Pfizer Deutschland GmbH, Berlin, Germany, 4Bristol Myers Squibb, Munich, Germany, 5Bristol Myers Squibb, Rueil-Malmaison, France, 6Elsevier Health Analytics, Berlin, Germany Introduction Sensitivity Analysis Figure 2: Unadjusted event rates (per 100 person-years) and adjusted hazard ratios with 95% . Analyses with the highest approved doses (2x5mg for apixaban, 2x150 mg for dabigatran, and 1x20 mg for confidence intervals for each pairwise comparison (apixaban, dabigatran, and rivaroxaban each vs . Oral anticoagulation therapy (OAC) substantially reduces the risk of stroke in patients with non-valvular atrial rivaroxaban) were performed. phenprocoumon) fibrillation (NVAF) (1). The most important side effect of OAC is bleeding. phenprocoumon . Since 2011 non-vitamin K-oral anticoagulants (NOACs) are available for stroke prevention in patients with Results NVAF. Among 35,013 eligible patients, 3,633 (10.38%) were initiated on apixaban, 3,138 (8.96%) on dabigatran, . NOACs are easier to use than vitamin-K antagonists (VKA) and have demonstrated equivalent or even 12,063 (34.45%) on rivaroxaban, and 16,179 (46.21%) on phenprocoumon. superior efficacy and safety in comparison to VKA in large randomized control trials (RCTs) (2). The mean follow-up for patients initiated on apixaban was 220.79 days, dabigatran was 264.45 days, . -

PDF Download

Review Article 201 How Do I Reverse Oral and Parenteral Anticoagulants? Wie Reversiere ich die Wirkung von Oralen und Parenteralen Antikoagulanzien? Jürgen Koscielny1 Edita Rutkauskaite1 Christoph Sucker2 Christian von Heymann3 1 Charité, Universitätsmedizin Berlin, Gerinnungsambulanz mit Address for correspondence Jürgen Koscielny, Charité, Hämophiliezentrum im Ambulanten, Gesundheitszentrum (AGZ), Universitätsmedizin Berlin, Gerinnungsambulanz mit Berlin, Germany HämophiliezentrumimAmbulantenGesundheitszentrum(AGZ), 2 Gerinnungszentrum Berlin Dr. Sucker, Berlin, Germany Berlin, Germany (e-mail: [email protected]). 3 Klinik für Anästhesie, Intensivmedizin, Notfallmedizin und Schmerztherapie, Vivantes Klinikum, Im Friedrichshain, Berlin, Germany Hämostaseologie 2020;40:201–213. Abstract An understanding of reversal strategies alone is important to safely and effectively care for patients in cases of bleeding or invasive procedures. The recent diversification in the number of licensed anticoagulants makes an understanding of drug-specific reversal strategies essential. Intravenous or oral vitamin K can reverse the effect of vitamin K antagonists (VKAs) within 12 to 48 hours and is indicated for any bleeding or an international normalized ratio >10 or 4.5 to 10 in patients with additional risk factors for bleeding. Furthermore, an additional administration of prothrombin complex concentrate (PCC) may be necessary in cases of major bleeding related to VKA. Protamine (chloride or sulfate) fully reverses the effect of unfractionated heparin and partially in low-molecular-weight heparin. Idarucizumab has been approved for dabigatran reversal, whereas andexanet alfa is approved for the reversal of some oral factor Xa inhibitors (apixaban, rivaroxaban). PCC seems to enhance the haemo- static potential for the reversal of the effect of FXa-inhibitors. So far, there are promising but only limited data on the efficacy of this approach available. -

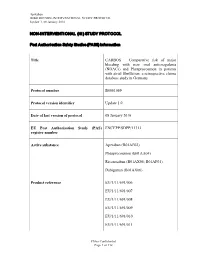

Non-Interventional (Ni) Study Protocol

Apixaban B0661069 NON-INTERVENTIONAL STUDY PROTOCOL Update 1, 08 January 2016 NON-INTERVENTIONAL (NI) STUDY PROTOCOL Post Author isation Safet y St udi es (PA SS) infor mation Title CARBOS – Comparative risk of major bleeding with new oral anticoagulants (NOACs) and Phenprocoumon in patients with atrial fibrillation: a retrospective claims database study in Germany Protocol number B0661069 Protocol version identifier Update 1.0 Date of last version of protocol 08 January 2016 EU Post Authorisation Study (PAS) ENCEPP/SDPP/11313 register number Active substance Apixaban (B01AF02) Phenprocoumon (B01AA04) Rivaroxaban (B01AX06; B01AF01) Dabigatran (B01AX06) Product reference EU/1/11/691/006 EU/1/11/691/007 EU/1/11/691/008 EU/1/11/691/009 EU/1/11/691/010 EU/1/11/691/011 Pfizer Confidential Page 1 of 112 Apixaban B0661069 NON-INTERVENTIONAL STUDY PROTOCOL Update 1, 08 January 2016 EU/1/11/691/012 EU/1/11/691/014 Procedure number Not Available Marketing Authorisation Holder (MAH) Pfizer Pharma GmbH Joint PASS No Research question and objectives The aim of this study is to investigate whether there are differences in the occurrence of major bleeding events in patients with NVAF and prescribed oral anticoagulation therapies in a real-world setting. It will be investigated whether the occurrence of major bleeding events in NVAF patients under anticoagulant therapy differs between patients treated with VKA (e.g. Phenprocoumon) and patients treated with Apixaban, Dabigatran or Rivaroxaban respectively. Country of study Germany Author Fabian Volz Pfizer -

Viscoelastometry for Detecting Oral Anticoagulants

Groene et al. Thrombosis Journal (2021) 19:18 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12959-021-00267-w RESEARCH Open Access Viscoelastometry for detecting oral anticoagulants Philipp Groene1* , Daniela Wagner1, Tobias Kammerer1,2, Lars Kellert3, Andreas Giebl4, Steffen Massberg5 and Simon Thomas Schäfer1 Abstract Background: Determination of anticoagulant therapy is of pronounced interest in emergency situations. However, routine tests do not provide sufficient insight. This study was performed to investigate the impact of anticoagulants on the results of viscoelastometric assays using the ClotPro device. Methods: This prospective, observational study was conducted in patients receiving dabigatran, factor Xa (FXa)- inhibitors, phenprocoumon, low molecular weight heparin (LMWH) or unfractionated heparin (UFH) (local ethics committee approval number: 17–525-4). Healthy volunteers served as controls. Viscoelastometric assays were performed, including the extrinsic test (EX-test), intrinsic test (IN-test) Russel’s viper venom test (RVV-test), ecarin test (ECA-test), and the tissue plasminogen activator test (TPA-test). Results: 70 patients and 10 healthy volunteers were recruited. Clotting time in the EX-test (CTEX-test) was significantly prolonged versus controls by dabigatran, FXa inhibitors and phenprocoumon. CTIN-test was prolonged by dabigatran, FXa inhibitors and UFH. Dabigatran, FXa inhibitors and UFH significantly prolonged CTRVV-test in comparison with controls (median 200, 207 and 289 vs 63 s, respectively; all p < 0.0005). Only dabigatran elicited a significant increase in CTECA-test compared to controls (median 307 vs 73 s; p < 0.0001). CTECA-test correlated strongly with dabigatran plasma concentration (measured by anti-IIa activity; r = 0.9970; p < 0.0001) and provided 100% sensitivity and 100% specificity for detecting dabigatran. -

University of Groningen Pharmacogenetic Differences

University of Groningen Pharmacogenetic differences between warfarin, acenocoumarol and phenprocoumon Beinema, Maarten; Brouwers, Jacobus R. B. J.; Schalekamp, Tom; Wilffert, Bob Published in: Thrombosis and Haemostasis DOI: 10.1160/TH08-04-0116 IMPORTANT NOTE: You are advised to consult the publisher's version (publisher's PDF) if you wish to cite from it. Please check the document version below. Document Version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Publication date: 2008 Link to publication in University of Groningen/UMCG research database Citation for published version (APA): Beinema, M., Brouwers, J. R. B. J., Schalekamp, T., & Wilffert, B. (2008). Pharmacogenetic differences between warfarin, acenocoumarol and phenprocoumon. Thrombosis and Haemostasis, 100(6), 1052-1057. https://doi.org/10.1160/TH08-04-0116 Copyright Other than for strictly personal use, it is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). The publication may also be distributed here under the terms of Article 25fa of the Dutch Copyright Act, indicated by the “Taverne” license. More information can be found on the University of Groningen website: https://www.rug.nl/library/open-access/self-archiving-pure/taverne- amendment. Take-down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Downloaded from the University of Groningen/UMCG research database (Pure): http://www.rug.nl/research/portal. -

Treatment of Pregnancy-Associated Venous Thromboembolism – Position Paper from the Working Group in Women’S Health of the Society of Thrombosis and Haemostasis (GTH)

103 Review Treatment of pregnancy-associated venous thromboembolism – position paper from the Working Group in Women’s Health of the Society of Thrombosis and Haemostasis (GTH) 1 Birgit Linnemann1, Ute Scholz2, Hannelore Rott3, Susan Halimeh3, Rainer Zotz4, Andrea Gerhardt5, Bettina Toth6, and Rupert Bauersachs7, 8 1 Medical Practice of Angiology and Haemostaseology, Praxis am Grüneburgweg, Frankfurt/Main, Germany 2 Zentrum für Blutgerinnungsstörungen, MVZ Labor Dr. Reising-Ackermann und Kollegen, Leipzig, Germany 3 Gerinnungszentrum Rhein Ruhr, Duisburg, Germany 4 Centrum für Blutgerinnungsstörungen und Transfusionsmedizin, Düsseldorf, Germany 5 Blutgerinnung Ulm, Germany 6 Gynäkologische Endokrinologie und Fertilitätsstörungen, Ruprecht-Karls-Universität Heidelberg, Germany 7 Klinikum Darmstadt, Klinik für Gefäßmedizin - Angiologie, Darmstadt, Germany 8 Centrum für Thrombose und Hämostase, Johannes-Gutenberg-Universität, Mainz, Germany Summary: Venous thromboembolism (VTE) is a major cause of maternal morbidity during pregnancy and the postpartum period. However, be- cause there is a lack of adequate study data, management strategies for pregnancy-associated VTE must be deduced from observational stu- dies and extrapolated from recommendations for non-pregnant patients. In this review, the members of the Working Group in Women’s Health of the Society of Thrombosis and Haemostasis (GTH) have summarised the evidence that is currently available in the literature to provide a practi- cal approach for treating pregnancy-associated VTE. Because heparins do not cross the placenta, weight-adjusted therapeutic-dose low mo- lecular weight heparin (LMWH) is the anticoagulant treatment of choice in cases of acute VTE during pregnancy. No differences between once and twice daily LMWH dosing regimens have been reported, but twice daily dosing seems to be advisable, at least peripartally. -

Revista5vol86ing Layout 1

961 REVISÃO ▲ Vasculopatia livedoide: uma doença cutânea intrigante* Livedoid vasculopathy: an intringuing cutaneous disease Paulo Ricardo Criado1 Evandro Ararigboia Rivitti2 Mirian Nacagami Sotto3 Neusa Yuriko Sakai Valente4 Valeria Aoki5 Jozelio Freire de Carvalho6 Cidia Vasconcellos7 Resumo: A vasculopatia livedoide é uma afecção cutânea oclusiva dos vasos sanguíneos da derme, de caráter pauci-inflamatório ou não-inflamatório. Caracteriza-se pela presença de lesões maculosas ou papulosas, eritêmato-purpúricas, nas pernas, especialmente nos tornozelos e pés, as quais produzem ulcerações intensamente dolorosas, que originam cicatrizes atróficas esbranquiçadas, denominadas “atrofia branca”. Nesta revisão, abordamos os estudos e relatos de caso da literatura médica referentes às associações etiopatogênicas da doença, particularmente as que se referem aos estados de trombofi- lia, seus achados histopatológicos e abordagens terapêuticas empregadas na difícil condução clínica des- tes casos. Palavras-chave: Livedo reticular; Trombofilia; Trombose; Trombose venosa; Úlcera da perna Abstract: Livedoid vasculopathy is a skin disease that occludes the blood vessels of the dermis. It has a pauciinflammatory or non-inflammatory nature. It is characterized by the presence of macular or papu- lar, erythematous-purpuric lesions affecting the legs, especially the ankles and feet, and producing intensely painful ulcerations, which cause white atrophic scars called "atrophie blanche". This review includes studies and case reports found in the medical literature regarding the etiopathogenic associa- tions of the disease, particularly those related to thrombophilia, their histopathological findings and the therapeutic approaches used in the difficult clinical management of these cases. Keywords: Leg ulcer; Livedo reticularis; Thrombophilia; Thrombosis; Venous thrombosis Recebido em 04.10.2010. Aprovado pelo Conselho Consultivo e aceito para publicação em 27.12.2010.