Verney's Duodecimal Chess

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fide Online Chess Regulations

Annex 6.4 FIDE ONLINE CHESS REGULATIONS Introduction The FIDE Online Chess Regulations are intended to cover all competitions where players play on the virtual chessboard and transmit moves via the internet. Wherever possible, these Regulations are intended to be identical to the FIDE Laws of Chess and related FIDE competition regulations. They are intended for use by players and arbiters in official FIDE online competitions, and as a technical specification for online chess platforms hosting these competitions. These Regulations cannot cover all possible situations that may arise during a competition, but it should be possible for an arbiter with the necessary competence, sound judgment, and objectivity, to arrive at the correct decision based on his/her understanding of these Regulations. Annex 6.4 Contents Introduction ..................................................................................................................................... 1 Part I: Basic Rules of Play ................................................................................................................. 3 Article 1: Application of the FIDE Laws of Chess .............................................................................. 3 Part II: Online Chess Rules ............................................................................................................... 3 Article 2: Playing Zone ................................................................................................................... 3 Article 3: Moving the Pieces on -

A Combinatorial Game Theoretic Analysis of Chess Endgames

A COMBINATORIAL GAME THEORETIC ANALYSIS OF CHESS ENDGAMES QINGYUN WU, FRANK YU,¨ MICHAEL LANDRY 1. Abstract In this paper, we attempt to analyze Chess endgames using combinatorial game theory. This is a challenge, because much of combinatorial game theory applies only to games under normal play, in which players move according to a set of rules that define the game, and the last player to move wins. A game of Chess ends either in a draw (as in the game above) or when one of the players achieves checkmate. As such, the game of chess does not immediately lend itself to this type of analysis. However, we found that when we redefined certain aspects of chess, there were useful applications of the theory. (Note: We assume the reader has a knowledge of the rules of Chess prior to reading. Also, we will associate Left with white and Right with black). We first look at positions of chess involving only pawns and no kings. We treat these as combinatorial games under normal play, but with the modification that creating a passed pawn is also a win; the assumption is that promoting a pawn will ultimately lead to checkmate. Just using pawns, we have found chess positions that are equal to the games 0, 1, 2, ?, ", #, and Tiny 1. Next, we bring kings onto the chessboard and construct positions that act as game sums of the numbers and infinitesimals we found. The point is that these carefully constructed positions are games of chess played according to the rules of chess that act like sums of combinatorial games under normal play. -

Computer Analysis of World Chess Champions 65

Computer Analysis of World Chess Champions 65 COMPUTER ANALYSIS OF WORLD CHESS CHAMPIONS1 Matej Guid2 and Ivan Bratko2 Ljubljana, Slovenia ABSTRACT Who is the best chess player of all time? Chess players are often interested in this question that has never been answered authoritatively, because it requires a comparison between chess players of different eras who never met across the board. In this contribution, we attempt to make such a comparison. It is based on the evaluation of the games played by the World Chess Champions in their championship matches. The evaluation is performed by the chess-playing program CRAFTY. For this purpose we slightly adapted CRAFTY. Our analysis takes into account the differences in players' styles to compensate the fact that calm positional players in their typical games have less chance to commit gross tactical errors than aggressive tactical players. Therefore, we designed a method to assess the difculty of positions. Some of the results of this computer analysis might be quite surprising. Overall, the results can be nicely interpreted by a chess expert. 1. INTRODUCTION Who is the best chess player of all time? This is a frequently posed and interesting question, to which there is no well founded, objective answer, because it requires a comparison between chess players of different eras who never met across the board. With the emergence of high-quality chess programs a possibility of such an objective comparison arises. However, so far computers were mostly used as a tool for statistical analysis of the players' results. Such statistical analyses often do neither reect the true strengths of the players, nor do they reect their quality of play. -

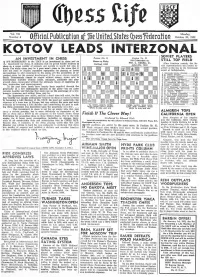

Kolov LEADS INTERZONAL SOVIET PLAYERS an INVESTMENT in CHESS Po~;T;On No

Vol. Vll Monday; N umber 4 Offjeitll Publication of me Unttecl States (bessTederation October 20, 1952 KOlOV LEADS INTERZONAL SOVIET PLAYERS AN INVESTMENT IN CHESS Po~;t;on No. 91 POI;l;"n No. 92 IFE MEMBERSHIP in the USCF is an investment in chess and an Euwe vs. Flohr STILL TOP FIELD L investment for chess. It indicates that its proud holder believes in C.1rIbad, 1932 After fOUl't~n rounds, the S0- chess ns a cause worthy of support, not merely in words but also in viet rcpresentatives still erowd to deeds. For while chess may be a poor man's game in the sense that it gether at the top in the Intel'l'onal does not need or require expensive equipment fm' playing or lavish event at Saltsjobaden. surroundings to add enjoyment to the game, yet the promotion of or· 1. Alexander Kot()v (Russia) .w._.w .... 12-1 ganized chess for the general development of the g'lmc ~ Iway s requires ~: ~ ~~~~(~tu(~~:I;,.i ar ·::::~ ::::::::::~ ~!~t funds. Tournaments cannot be staged without money, teams sent to international matches without funds, collegiate, scholastic and play· ;: t.~h!"'s~~;o il(\~::~~ ry i.. ··::::::::::::ij ); ~.~ ground chess encouraged without the adequate meuns of liupplying ad· 6. Gidcon S tahl ~rc: (Sweden) ...... 81-5l vice, instruction and encouragement. ~: ~,:ct.~.:~bG~~gO~~(t3Ji;Oi· · ·:::: ::::::7i~~ In the past these funds have largely been supplied through the J~: ~~j~hk Elrs'l;~san(A~~;t~~~ ) ::::6i1~ generosity of a few enthusiastic patrons of the game-but no game 11. -

FIDE Laws of Chess

FIDE Laws of Chess FIDE Laws of Chess cover over-the-board play. The Laws of Chess have two parts: 1. Basic Rules of Play and 2. Competition Rules. The English text is the authentic version of the Laws of Chess (which was adopted at the 84th FIDE Congress at Tallinn (Estonia) coming into force on 1 July 2014. In these Laws the words ‘he’, ‘him’, and ‘his’ shall be considered to include ‘she’ and ‘her’. PREFACE The Laws of Chess cannot cover all possible situations that may arise during a game, nor can they regulate all administrative questions. Where cases are not precisely regulated by an Article of the Laws, it should be possible to reach a correct decision by studying analogous situations which are discussed in the Laws. The Laws assume that arbiters have the necessary competence, sound judgement and absolute objectivity. Too detailed a rule might deprive the arbiter of his freedom of judgement and thus prevent him from finding a solution to a problem dictated by fairness, logic and special factors. FIDE appeals to all chess players and federations to accept this view. A necessary condition for a game to be rated by FIDE is that it shall be played according to the FIDE Laws of Chess. It is recommended that competitive games not rated by FIDE be played according to the FIDE Laws of Chess. Member federations may ask FIDE to give a ruling on matters relating to the Laws of Chess. BASIC RULES OF PLAY Article 1: The nature and objectives of the game of chess 1.1 The game of chess is played between two opponents who move their pieces on a square board called a ‘chessboard’. -

A Manual in Chess Game the Unity Asset

Manual to Chess Game – Unity Asset Introduction This document details how the unity asset called Chess Game works. If you have any questions you can contact me at [email protected] Code documentation: http://readytechtools.com/ChessGame/ManualChessGame.pdf Content Introduction.................................................................................................................................................1 Board representation..................................................................................................................................2 Generating Moves.......................................................................................................................................3 Testing legality of moves.............................................................................................................................3 Special Moves(Castling, EnPassant and Pawn promotions).........................................................................4 AI Opponent................................................................................................................................................4 FAQ..............................................................................................................................................................5 Board representation The board is represented in two ways. The visual board that the end user sees and interacts. This visual board is primarily handled by cgChessBoardScript.cs which inherits from MonoBehaviour and has editable properties -

3Rd Interzonal Individual Tournament Invitation

INTERNATIONAL CORRESPONDENCE CHESS FEDERATION SIM Everdinand Knol 138 Blom Street 0184 Silverton South Africa [email protected] Announcement of the 3rd Interzonal Individual Tournament Dear Correspondence Chess Friends With the restructuring of zones as well as a few other bureaucratic activities, now something of the past, we are ready to proceed with the third ICCF Interzonal Individual Tournament. The details are as follows: • The purpose of this event is to develop the spirit of amici sumus among players worldwide (in all three ICCF Zones) and to provide opportunities to qualify for title norms. • Participants must have an ICCF rating of between 2200 and 2375. • This event will start with a preliminary stage consisting of groups of 9 players each in categories 1 to 3. • The top three finishers of each group will qualify for the semi final stage in at least category 4. • To achieve this category some higher rated players will be invited to participate in the semi-finals. • The semi final will produce players for the final which will be at least a category 7. • Again some higher rated players will be invited to participate to achieve this category in the final. • This tournament is played on a two yearly basis. • Players must enter via their national delegates to their zonal directors who will decide which players are to represent the zone. • Entries must be forwarded to me by the zonal directors only!! • The quota per zone is 36 players (a total of 108). • The entry fee will be 50 Euro cents per game per player (8 x 50c = 4 Euro) for non developing countries while players from developing countries will receive a 50% discount. -

Proposal to Encode Heterodox Chess Symbols in the UCS Source: Garth Wallace Status: Individual Contribution Date: 2016-10-25

Title: Proposal to Encode Heterodox Chess Symbols in the UCS Source: Garth Wallace Status: Individual Contribution Date: 2016-10-25 Introduction The UCS contains symbols for the game of chess in the Miscellaneous Symbols block. These are used in figurine notation, a common variation on algebraic notation in which pieces are represented in running text using the same symbols as are found in diagrams. While the symbols already encoded in Unicode are sufficient for use in the orthodox game, they are insufficient for many chess problems and variant games, which make use of extended sets. 1. Fairy chess problems The presentation of chess positions as puzzles to be solved predates the existence of the modern game, dating back to the mansūbāt composed for shatranj, the Muslim predecessor of chess. In modern chess problems, a position is provided along with a stipulation such as “white to move and mate in two”, and the solver is tasked with finding a move (called a “key”) that satisfies the stipulation regardless of a hypothetical opposing player’s moves in response. These solutions are given in the same notation as lines of play in over-the-board games: typically algebraic notation, using abbreviations for the names of pieces, or figurine algebraic notation. Problem composers have not limited themselves to the materials of the conventional game, but have experimented with different board sizes and geometries, altered rules, goals other than checkmate, and different pieces. Problems that diverge from the standard game comprise a genre called “fairy chess”. Thomas Rayner Dawson, known as the “father of fairy chess”, pop- ularized the genre in the early 20th century. -

Basic Chess Rules

Basic chess rules Setting up the board: The board should be set up with the white square in the nearest row on the right, “white on the right”. If this isn’t done the king and queen will be mixed up. Shake hands across the board before the game starts. White always moves first. Ranks and files: Going from left to right, the vertical rows on the board, called files, are labeled a through h. The horizontal rows, called ranks, are numbered 1 to 8. The 1 is white’s side of the board; 8 is black’s side. This system can be used to show what square a piece is on in a way like the game Battleship. When the board is set up the square a1 will be on the white player’s left side. Pieces and how they move: In our club, once you move a piece and take your hand off it, you cannot change your move, unless your opponent lets you, which they do not need to do. However, you may touch a piece, consider a move, and put the piece back in its original position, as long as you don’t take your hand off of the piece during the process. Pawn (P): White pawns start on rank two, black pawns on rank 7. The first time a pawn is moved it can move forward either one or two ranks. It cannot jump over another piece. After it has moved once, whether it has moved up one or two, a pawn can only move one square forward at a time, and it cannot move backward. -

PGN/AN Verification for Legal Chess Gameplay

PGN/AN Verification for Legal Chess Gameplay Neil Shah Guru Prashanth [email protected] [email protected] May 10, 2015 Abstract Chess has been widely regarded as one of the world's most popular games through the past several centuries. One of the modern ways in which chess games are recorded for analysis is through the PGN/AN (Portable Game Notation/Algebraic Notation) standard, which enforces a strict set of rules for denoting moves made by each player. In this work, we examine the use of PGN/AN to record and describe moves with the intent of building a system to verify PGN/AN in order to check for validity and legality of chess games. To do so, we formally outline the abstract syntax of PGN/AN movetext and subsequently define denotational state-transition and associated termination semantics of this notation. 1 Introduction Chess is a two-player strategy board game which is played on an eight-by-eight checkered board with 64 squares. There are two players (playing with white and black pieces, respectively), which move in alternating fashion. Each player starts the game with a total of 16 pieces: one king, one queen, two rooks, two knights, two bishops and eight pawns. Each of the pieces moves in a different fashion. The game ends when one player checkmates the opponents' king by placing it under threat of capture, with no defensive moves left playable by the losing player. Games can also end with a player's resignation or mutual stalemate/draw. We examine the particulars of piece movements later in this paper. -

Chess-Training-Guide.Pdf

Q Chess Training Guide K for Teachers and Parents Created by Grandmaster Susan Polgar U.S. Chess Hall of Fame Inductee President and Founder of the Susan Polgar Foundation Director of SPICE (Susan Polgar Institute for Chess Excellence) at Webster University FIDE Senior Chess Trainer 2006 Women’s World Chess Cup Champion Winner of 4 Women’s World Chess Championships The only World Champion in history to win the Triple-Crown (Blitz, Rapid and Classical) 12 Olympic Medals (5 Gold, 4 Silver, 3 Bronze) 3-time US Open Blitz Champion #1 ranked woman player in the United States Ranked #1 in the world at age 15 and in the top 3 for about 25 consecutive years 1st woman in history to qualify for the Men’s World Championship 1st woman in history to earn the Grandmaster title 1st woman in history to coach a Men's Division I team to 7 consecutive Final Four Championships 1st woman in history to coach the #1 ranked Men's Division I team in the nation pnlrqk KQRLNP Get Smart! Play Chess! www.ChessDailyNews.com www.twitter.com/SusanPolgar www.facebook.com/SusanPolgarChess www.instagram.com/SusanPolgarChess www.SusanPolgar.com www.SusanPolgarFoundation.org SPF Chess Training Program for Teachers © Page 1 7/2/2019 Lesson 1 Lesson goals: Excite kids about the fun game of chess Relate the cool history of chess Incorporate chess with education: Learning about India and Persia Incorporate chess with education: Learning about the chess board and its coordinates Who invented chess and why? Talk about India / Persia – connects to Geography Tell the story of “seed”. -

Rules of Chess960

Rules of Chess960 A little known and long-discarded offshoot of Classical Chess is the realm of so-called "Randomized Chess" in its various forms. Chess960 stands for Bobby Fischer's new and improved version of "Randomized Chess". Chess960 uses algebraic notation exclusively At the start of every game of a Chess960 game, both players Pawns are set up exactly as they are at the start of every game of Classical Chess. In Chess960, just before the start of every game, both players pieces on their respective back rows receive an identical random shuffle using the Chess960 Computerized Shuffler, which is programmed to set up the pieces in any combination, with the provisos that one Rook has to be to the left and one Rook has to be to the right of the King, and one Bishop has to be on a light- colored square and one Bishop has to be on a dark-colored square. White and Black have identical positions. From behind their respective Pawns the opponents pieces are facing each other directly, symmetrically. Thus for example, if the shuffler places White's back row pieces in the following position: Ra1, Bb1, Kc1, Nd1, Be1, Nf1, Rg1, Qh1, it will place Black's back row Pieces in the following position, Ra8, Bb8, Kc8, Nd8, Be8, Nf8, Rg8, Qh8, etc. (See diagram) In Chess960 there are 960 possible starting positions, the Classical Chess starting position and 959 other starting positions. Of necessity, In Chess960 the castling rule is somewhat modified and broadened to allow for the possibility of each player castling either on or into his or her left side or on or into his or her right side of the board from all of these 960 starting positions.