China-Philippines Joint Development of South China Sea Hydrocarbon Resources: Challenges and Future Priorities

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PH Braces for Fuel Crisis After Attacks on Saudi Oil Facilities

WEEKLY ISSUE @FilAmNewspaper www.filamstar.com Vol. IX Issue 545 1028 Mission Street, 2/F, San Francisco, CA 94103 Email: [email protected] Tel. (415) 593-5955 or (650) 278-0692 September 19-25, 2019 Elaine Chao (Photo: Wikimedia) VP Robredo faces resolution of her fraud, sedition cases Trump Transpo Sec. By Beting Laygo Dolor acting as presidential electoral tribu- by the Commission on Elections, which Chao under scrutiny Contributing Editor nal (PET) is expected to release the Marcos charged was an election taint- US NEWS | A2 decision on the vote recount of the ed with fraud and massive cheating. ANYTIME within the next week or 2016 elections filed by former sen- To prove his claim, Marcos so, Vice-president Leni Robredo can ator Ferdinand Marcos, Jr. against requested and was granted a manual expect a decision to be handed out in her. recount of votes in three provinces. two high-profile cases involving her. Robredo defeated Marcos by some TO PAGE A7 VP Leni Robredo (Photo: Facebook) In the first, the Supreme Court 250,000 votes based on the final tally ■ By Daniel Llanto FilAm Star Correspondent IN THE wake of the drone attacks on Saudi Arabia’s oil facilities, Foreign PH braces for fuel Affairs Sec. Teodoro Locsin Jr. said Riza Hontiveros (Photo: Facebook) the loss of half of the world’s top oil Divorce bill in producer is so serious it could affect the country “deeply” and cause the “Philip- crisis after attacks discussion at PH Senate pine boat to tip over.” PH NEWS | A3 “This is serious,” Locsin tweeted. -

1623635494-13 JUNE 2021.Pdf

Sacrifices of front-liners sustain battle vs. Covid-19 By Joyce Ann L. Rocamora June 12, 2021, 7:35 HERO WORSHIP. President Rodrigo Duterte (right) attends an Independence Day celebration in Malolos City, Bulacan on Saturday (June 12, 2021). He said all Filipinos, especially front-liners, battling the Covid-19 pandemic are heroes. (Photo courtesy of Sen. Bong Go) MANILA – President Rodrigo Duterte on Saturday honored as "modern heroes" the Filipino people who continuously battle the Covid-19 pandemic. In his Independence Day speech at the Bulacan Provincial Capitol in Malolos City, Duterte said it is an occasion to “honor our modern-day heroes — our healthcare workers, law enforcement officers, and other front-liners who have been instrumental in our fight against the Covid-19 pandemic". He also recognized the sacrifices made by front-liners at the risk of their lives. "In the past year, they have risked their own lives and sacrificed their own comfort and security to ensure that our society will continue to function despite this crisis. Maraming pong salamat sa inyong pagmalasakit at serbisyo (Thank you very much for your compassion and service)," he said. The President said a wall of heroes is now being built at the Libingan ng mga Bayani in Fort Bonifacio, Taguig City where the names of doctors, nurses, and medical personnel who died due to Covid-19 will be inscribed. "At lahat ‘yung namatay na mga duktor, mga nurses, ‘yung mga attendants na nahawa ng Covid (All the doctors, nurses, and attendants who died due to Covid) will be honored by their names inscribed on that wall. -

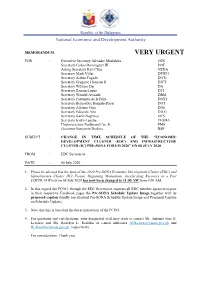

Change in Schedule of Pre-SONA Forum 2020

Republic of the Philippines National Economic and Development Authority MEMORANDUM VERY URGENT FOR : Executive Secretary Salvador Medialdea OES Secretary Carlos Dominguez III DOF Acting Secretary Karl Chua NEDA Secretary Mark Villar DPWH Secretary Arthur Tugade DOTr Secretary Gregorio Honasan II DICT Secretary William Dar DA Secretary Ramon Lopez DTI Secretary Wendel Avisado DBM Secretary Fortunato de la Peña DOST Secretary Bernadette Romulo-Puyat DOT Secretary Alfonso Cusi DOE Secretary Eduardo Año DILG Secretary Karlo Nograles OCS Secretary Isidro Lapeña TESDA Undersecretary Ferdinand Cui, Jr. PMS Governor Benjamin Diokno BSP SUBJECT : CHANGE IN TIME SCHEDULE OF THE “ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT CLUSTER (EDC) AND INFRASTRUCTURE CLUSTER (IC) PRE-SONA FORUM 2020” ON 08 JULY 2020 FROM : EDC Secretariat DATE : 06 July 2020 1. Please be advised that the time of the 2020 Pre-SONA Economic Development Cluster (EDC) and Infrastructure Cluster (IC) Forum: Regaining Momentum, Accelerating Recovery in a Post COVID-19 World on 08 July 2020 has now been changed to 11:00 AM from 9:00 AM. 2. In this regard, the PCOO, through the EDC Secretariat, requests all EDC member agencies to post in their respective Facebook pages the Pre-SONA Schedule Update Image together with its proposed caption (kindly see attached Pre-SONA Schedule Update Image and Proposed Caption on Schedule Update). 3. Note that this is based on the latest instruction of the PCOO. 4. For questions and clarifications, your designated staff may wish to contact Mr. Antonio Jose G. Leuterio and Ms. Rodelyn L. Rodillas at e-mail addresses [email protected] and [email protected], respectively. -

99Th Issue Aug. 9-15, 2021

“Radiating positivity, creating connectivity” CEBU BUSINESS Room 310-A, 3rd floor WDC Bldg. Osmeña Blvd., Cebu City You may visit Cebu Business Week WEEK Facebook page. August 9 - 15, 2021 Volume 3, Series 99 www.cebubusinessweek.com 12 PAGES P15.00 SARA TO RUN NOT AS PDP Digong’s men fear they will be out by July 1, 2022 A NEW umbrella orga- ban, who will pose for Sena- By: ELIAS O. BAQUERO maybe testing the water if his sincerity. They may betray nization was hatched to con- tor Christopher “Bong” Go for endorsement will be accept- you in the last minute,” Dela solidate all groups supporting president and PRRD for vice tion of the Philippines) which able to the people. Fuente quoted Sara. the candidacy of Davao City president. is now lorded with Chinese “Senator Bong Go’s rat- He said some Cebu poli- Mayor Sara Duterte Carpio for He said the group of executives,” Dela Fuente said. ing is very low because as I ticians campaigned for then president nationwide. Matibag and Cusi are not in He added that when Sara said in past interviews, the presidential candidate Je- Dr. Winley Sanchez Dela good terms with Sara. They took over as Davao City may- Duterte legacy cannot be jomar Binay in 2016 and after Fuente, founding chair of Or- are for Go in the hope that or, all the officials appointed passed on to other person Binay gave them huge cam- dinaryong Lungsoranon sa they will remain in power by by her father when he was like Go. -

President Rodrigo Duterte's Economic Team

Received by NSD/FARA Registration Unit 07/31/2020 6:07:26 PM Media Releases (February to June 2020) 1. March 16 Media Release: Philippine DoF pledges over USD525 million to support health authorities and provide economic relief during COVID-19 March 16, 2020 PRESS RELEASE Gov’t economic team rolls out P27.1 B package vs COVID-19 pandemic President Rodrigo Duterte’s economic team has announced a P27.i-billion package of priority actions to help frontliners fight the 2019 coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic and provide economic relief to people and sectors affected by the virus-induced slowdown in economic activity. The package consists of government initiatives to better equip our health authorities in fighting COVID-19 and also for the relief and recovery efforts for infected people and the various sectors now reeling from the adverse impact of the lethal pathogen. Finance Secretary Carlos Dominguez III, who chairs the Duterte Cabinet's Economic Development Cluster (EDC), said on Monday the measures in the package “are designed to do two things: First is to ensure that funding is available for the efforts of the Department of Health (DOH) to contain the spread of COVID-19. Second is to provide economic relief to those whose businesses and livelihoods have been affected by the spread of this disease.” “As directed by President Duterte, the government will provide targeted and direct programs to guarantee that benefits will go to our workers and other affected sectors. We have enough but limited resources, so our job is to make sure that we have sufficient funds for programs mitigating the adverse effects of COVID-19 on our economy,” he added. -

President Duterte: a Different Philippine Leader

This document is downloaded from DR‑NTU (https://dr.ntu.edu.sg) Nanyang Technological University, Singapore. President Duterte: A Different Philippine Leader Desker, Barry 2016 Desker, B. (2016). President Duterte: A Different Philippine Leader. (RSIS Commentaries, No. 145). RSIS Commentaries. Singapore: Nanyang Technological University. https://hdl.handle.net/10356/81314 Nanyang Technological University Downloaded on 01 Oct 2021 00:09:11 SGT www.rsis.edu.sg No. 145 – 14 June 2016 RSIS Commentary is a platform to provide timely and, where appropriate, policy-relevant commentary and analysis of topical issues and contemporary developments. The views of the authors are their own and do not represent the official position of the S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies, NTU. These commentaries may be reproduced electronically or in print with prior permission from RSIS and due recognition to the author(s) and RSIS. Please email: [email protected] for feedback to the Editor RSIS Commentary, Yang Razali Kassim. President Duterte: A Different Philippine Leader By Barry Desker Synopsis The Philippines’ new president Rodrigo Duterte will act differently from his predecessors. There is a need for a more layered understanding of the man and his policies. Commentary SINCE THE election of Davao City Mayor Rodrigo Duterte as the next Philippine President in a landslide victory on 9 May 2016, the regional and international media have highlighted his outrageous remarks on various sensitive topics. For instance he backed the extra-judicial killings of drug dealers, alleged that journalists were killed because they were corrupt and called Philippine bishops critical of him “sons of whores”, among other crude comments. -

Final GPDP Completion Report

GAS POLICY DEVELOPMENT PROJECT Completion Report SEPTEMBER 2018-JANUARY 2020 This document is made possible by the generous support of the American people through the United States Department of State-Bureau of Energy Resources (USDS-ENR). The contents are the responsibility of the GPDP Team and do not necessarily reflect the views of the USDS-ENR, the United States Government or the UPSCRFI. *A supplementary report covering the details of activities for February to June 2020 will be submitted to USDS. ABOUT GAS POLICY GPDP Management and Staff DEVELOPMENT PROJECT Ramon Clarete Project Director The Gas Policy Development Project (GPDP) aims to provide technical assistance to the Philippine Department Dennis Mapa Project Director for of Energy (DOE) in implementing the Philippine Finance and Administration Downstream Natural Gas Regulation (PDNGR) Department Majah-Leah Ravago Project Director for Circular (DC) 2017-11-0012. The Project includes capacity- Research building activities, provision of technical advice and Belyn Rafael Deputy Project Director guidance to implement the PDNGR, conduct of research J. Kathleen Magadia Research and on natural gas industry in the Philippines, and assistance Communications Specialist in the improvement of PDNGR-related policies. Jennylene Layaoen Capacity Building Specialist Renzi Frias Project Technical Officer Specifically, the Project aims to: Maribel Testa Finance and Administration Coordinator 1. Strengthen the capacity to implement the Circular with particular focus on best practices and lessons learned to Alfred Recio Accountant evaluate natural gas-related project applications; Helen Santos Administrative Officer Duchees Alvarez Project Assistant 2. Recommend technical, economic, and financial Raul Fabella Research Fellow guidelines, criteria, and systems that could be used as a Karl Jandoc Research Fellow reference to evaluate project proposals for LNG facilities; 3. -

GUEST of HONOR and SPEAKER Executive Officers 2016-2017

1 Official Newsletter of Rotary Club of Manila 0 balita No. 3687, March 16, 2017 THE ROTARY CLUB OF MANILA BOARD OF DIRECTORS and GUEST OF HONOR AND SPEAKER Executive Officers 2016-2017 TEDDY OCAMPO President EBOT TAN Immediate Past President BABE ROMUALDEZ Vice President BOBBY JOSEPH ALBERT ALDAY SUSING PINEDA CHITO ZALDARRIAGA Hon. ALFONSO G. CUSI ART LOPEZ ISSAM ELDEBS Secretary Directors Department of Energy Republic of the Philippines NING LOPEZ Secretary KABALITA CHITO TAGAYSAY Let our Energy Reservoir find ways to power the nation to Treasurer its peak as he reinvigorates Asia’s First Rotary Club with his presence. LANCE MASTERS Sergeant-At-Arms What’s Inside AMADING VALDEZ Program 2 President’s Corner 3 Board Legal Adviser Guest Speaker’s Profile 4 The Week That Was 5-12 RCM Weekly Birthday Celebrants/ Books for 12 CALOY REYES Typhoon Victims of Tacloban Meeting Assistant Secretary International Yachting Fellowship/ Joint Club Meeting 13-14 On the lighter side 15-16 HERMIE ESGUERRA Public Health Nutrition and Child Care 17 Advertisement 18-20 RAOUL VILLEGAS Assistant Treasurer DAVE REYNOLDS Deputy Sergeant At Arms 2 PROGRAM RCM’s 33rd for Rotary Year 2016-17 Thursday, March 16, 2017, 12N, New World Makati Hotel Ballroom OIC/Moderator: PSAA”Gunter” Matschuck Program Timetable 11:30 AM Registration and Cocktails 12:25 PM Bell to be Rung: Members and Guests are PSAA”Gunter” Matschuck requested to be seated: OIC/Moderator 12:30 PM Call to order Pres. “Teddy” Ocampo Singing of the Republic of the Philippines National Anthem RCM WF Music Chorale Invocation Rtn. -

PROSPECTS and CHALLENGES from ”Pnoy” to “Prody”

PROSPECTS AND CHALLENGES FROM ”PNoy” TO “PRody” Ronald D. Holmes Pulse Asia Research Inc./ Australian National University/De La Salle University May 24, 2016 OUTLINE • On presidential transitions • Where we are coming from? • Hitting the ground running? • Implications for the bureaucracy • Where are we headed to? ON PRESIDENTIAL TRANSITIONS Transition period may be decisive, if not determinative of their political fate, like quick drying cement, a transition can rapidly lock in a new administration even before it gets moving Haider, 1981 A few questions: • Do presidential candidates consider preparing for governing to be as important as campaigning? • How do presidential candidates and newly elected presidents undertake such preparations? • Who are the players in the transition? • What makes an effective presidential transition? Players in the Transition • Leading roles – President, legacy oriented, credit-claiming – President-elect--fresh mandate, popular choice • Supporting roles – Legislators – Members of the cabinet – Foreign states – Career service – Voters/citizens – Social institutions (media, Church) What makes for a successful transition? • “…is one in which the national interest is advanced or at least is not harmed because a transfer of authority has taken place” (Clinton and Lang 1993) What makes for a successful transition? • “People, policy and perceptions” (Meese 2003) – People with a philosophical commitment to the president elect and his/her policies; of unquestioned integrity; proven competence; team player; toughness – Policy—important versus urgent the former drawing more time, energy and political capital – Perceptions—impression, both within and outside government, of how the new president and his administration performs What makes for a successful transition? • “incoming presidents should be held accountable for nimble governance and shrewd implementation of their priorities—nimble lion, shrewd fox and a benign puppy” (Walker 1993) THE OUTGOING PRESIDENT AND ADMINISTRATION PERFORMANCE RATINGS OF PRESIDENT BENIGNO S. -

7-CAAP Notes to Financial Statement

CIVIL AVIATION AUTHORITY OF THE PHILIPPINES NOTES TO THE FINANCIAL STATEMENTS I. GENERAL INFORMATION Agency Profile The Civil Aviation Authority of the Philippines (CAAP) was created by virtue of Republic Act No. 9497 otherwise known as the Civil Aviation Authority Act of 2008 which was enacted on March 4, 2008. Under its Transitory Provisions (Section 85, Chapter XII), Air Transportation Office (ATO), created under RA 776 also known as the “Civil Aeronautics Act of the Philippines” was abolished and all its powers, duties and rights vested by law and exercised by the said agency was transferred to CAAP. Likewise, all assets, real and personal property, funds and revenues owned by or vested in the different offices of the ATO, including all contracts, records and documents relating to the operations of the abolished agency and its offices and branches were similarly transferred to CAAP. Any real property owned by the national government or government-owned corporation or authority which is being used and utilized as office or facility by the ATO shall also be transferred and titled in favor of CAAP. The policy of the State to provide safe and efficient air transportation for the country as enunciated in Chapter I, Section 2 (Declaration of Policy) of RA 9497, to wit “It is hereby declared the policy of the State to provide safe and efficient air transport and regulatory services in the Philippines by providing for the creation of a civil aviation authority with jurisdiction over the restructuring of the civil system, the promotion, development and regulation of the technical, operational, safety and aviation security functions under the civil aviation authority” is the mandate of CAAP. -

Download the PDF File

ANTI-RED TAPE AUTHORITY 2018-2021 ACCOMPLISHMENT REPORT The Anti-Red Tape Authority was created by virtue of R.A. 11032 or the Ease of Doing Business and Efficient Government Service Delivery Act of 2018. ARTA is tasked to implement and oversee a national policy on anti-red tape and ease of doing business. Vision Our vision is a fair and citizen-centric Philippine government, which enables a vibrant business environment and a high-trust society. Mission To achieve our vision, we will transform the way the government enables its citizens and stakeholders through collaboration, technology, and good regulatory practices. Core Values Integrity Citizen-centric Innovation IRR Signing Pursuant to Section 30 of RA 11032, the Anti-Red Tape Authority (ARTA), with the Civil Service Commission (CSC) and Department of Trade and Industry (DTI) must recommend for approval the Implementing Rules and Regulation (IRR) within ninety (90) days from the effectivity of the Act. Under the leadership of Director General Belgica, the draft IRR was reviewed, revamped, and signed in just 7 working days after his oath taking. The IRR was signed on July 17, 2019, together with the DTI Secretary and CSC Chairperson. The published version of the IRR can be accessed at the Anti-Red Tape Authority Website, www.arta.gov.ph. ARTA Major Program 2018-2021 Since it’s inception, ARTA has hit the ground running in ensuring that its mandate is implemented. At the same time, ARTA has always proactively heeded the directive of the President to deliver efficient government service. SONA 2019 He also reiterated the need for government service that is client-friendly, which is why ARTA committed itself to ensuring this through surprise inspections. -

Philippine Update

WeeklyPhilippine Update WEEKLY UPDATE WE TELL IT LIKE IT IS VOLUME I, NO. 7 Feb. 13 - 17, 2017 _______ ___ _ ____ __ ___PHIL. Copyright 2002 _ THE WALLACE BUSINESS FORUM, INC. accepts no liability for the accuracy of the data or for the editorial views contained in this report.__ Political Court upholds Marcos protest "Quotes The Supreme Court, sitting as the Presidential Electoral Tribunal (PET), has allowed former senator Ferdinand “Bongbong” Marcos Jr.’s election protest against Vice President Maria of the Week" Leonor “Leni” Robredo to proceed, declaring it “sufficient in form and substance.” In an 8- page resolution dated January 24, the tribunal dismissed VP Robredo’s claim that Mr. Marcos’ accusations of cheating and vote-buying were just a “series of wild accusations, guesses and surmises.” The tribunal also rejected VP Robredo’s argument that it had no “Release Napoles, the number one enabler of plunderers jurisdiction over the case. VP Robredo claimed Mr. Marcos improperly raised before the in government, and we might as well dissolve our justice system and declare this government a electoral tribunal the authenticity of Certificates of Canvass (COCs), which she said should government of criminals, where the innocent are have been raised in a pre-proclamation case filed before Congress acting as the National imprisoned and the criminals liberated. Maybe next they will be setting free the convicted drug lords who testified Board of Canvassers. against me.” Senator Leila de Lima on the reported move by Duterte ready to resign if Trillanes proves P2Bn bank deposit allegation Solicitor-General Jose Calida to acquit pork barrel President Rodrigo Duterte denied Senator Antonio Trillanes IV’s allegation that he has P2 “queen” Janet Napoles.