Reflections on Much Loved

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An N U Al R Ep O R T 2018 Annual Report

ANNUAL REPORT 2018 ANNUAL REPORT The Annual Report in English is a translation of the French Document de référence provided for information purposes. This translation is qualified in its entirety by reference to the Document de référence. The Annual Report is available on the Company’s website www.vivendi.com II –— VIVENDI –— ANNUAL REPORT 2018 –— –— VIVENDI –— ANNUAL REPORT 2018 –— 01 Content QUESTIONS FOR YANNICK BOLLORÉ AND ARNAUD DE PUYFONTAINE 02 PROFILE OF THE GROUP — STRATEGY AND VALUE CREATION — BUSINESSES, FINANCIAL COMMUNICATION, TAX POLICY AND REGULATORY ENVIRONMENT — NON-FINANCIAL PERFORMANCE 04 1. Profile of the Group 06 1 2. Strategy and Value Creation 12 3. Businesses – Financial Communication – Tax Policy and Regulatory Environment 24 4. Non-financial Performance 48 RISK FACTORS — INTERNAL CONTROL AND RISK MANAGEMENT — COMPLIANCE POLICY 96 1. Risk Factors 98 2. Internal Control and Risk Management 102 2 3. Compliance Policy 108 CORPORATE GOVERNANCE OF VIVENDI — COMPENSATION OF CORPORATE OFFICERS OF VIVENDI — GENERAL INFORMATION ABOUT THE COMPANY 112 1. Corporate Governance of Vivendi 114 2. Compensation of Corporate Officers of Vivendi 150 3 3. General Information about the Company 184 FINANCIAL REPORT — STATUTORY AUDITORS’ REPORT ON THE CONSOLIDATED FINANCIAL STATEMENTS — CONSOLIDATED FINANCIAL STATEMENTS — STATUTORY AUDITORS’ REPORT ON THE FINANCIAL STATEMENTS — STATUTORY FINANCIAL STATEMENTS 196 Key Consolidated Financial Data for the last five years 198 4 I – 2018 Financial Report 199 II – Appendix to the Financial Report 222 III – Audited Consolidated Financial Statements for the year ended December 31, 2018 223 IV – 2018 Statutory Financial Statements 319 RECENT EVENTS — OUTLOOK 358 1. Recent Events 360 5 2. Outlook 361 RESPONSIBILITY FOR AUDITING THE FINANCIAL STATEMENTS 362 1. -

Un Film De Maryam Touzani

UN FILM DE MARYAM TOUZANI AVEC LUBNA AZABAL, NISRIN ERRADI, DOUAE BELKHAOUDA ALI N’ PRODUCTIONS, LES FILMS DU NOUVEAU MONDE, ARTEMIS PRODUCTIONS PRÉSENTENT UN FILM DE MARYAM TOUZANI AVEC LUBNA AZABAL, NISRIN ERRADI, DOUAE BELKHAOUDA 2019 / COULEUR / FORMATS : 5.1 & 1.85 / DURÉE : 98 MIN PROJECTIONS À CANNES LUNDI 20 MAI DISTRIBUTION RELATIONS PRESSE 11h30 et à 14h - salle Debussy AD VITAM MONICA DONATI 71, rue de la Fontaine au Roi Assistée de Barthélémy Dupont et Jérémie Charrier MARDI 21 MAI 75011 Paris 45. rue Georges Clemenceau - 06400 Cannes Tél. : 01 55 28 97 00 Tél. : 01 55 28 97 00 14h45 - Salle Bazin [email protected] Monica : 0623850618 Barthélemy: 0783260843 / Jérémie: 0608751691 [email protected] SYNOPSIS Dans la Médina de Casablanca, Abla, mère d’une fillette de 8 ans, tient un magasin de pâtisseries marocaines. Quand Samia, une jeune femme enceinte frappe à sa porte, Abla est loin d’imaginer que sa vie changera à jamais. Une rencontre fortuite du destin, deux femmes en fuite, et un chemin vers l’essentiel. « CE FILM EST NÉ D’UNE VRAIE RENCONTRE, NOTE D’INTENTION DOULOUREUSE MAIS INSPIRANTE, QUI A MARYAM TOUZANI LAISSÉ EN MOI DES TRACES INDÉLÉBILES.» Adam est l’histoire de deux solitudes qui s’apprivoisent, se confrontent, Cette Samia était douce, réservée, aimait la vie. Sa douleur, j’en ai été s’assemblent, de deux femmes prisonnières, chacune à sa manière, qui témoin. Sa joie de vivre, aussi. Et surtout, son déchirement vis-à-vis de cherchent à trouver refuge dans la fuite, le déni. cet enfant qu’elle se trouvait obligée d’après elle d’abandonner pour continuer son chemin. -

To Be Unaware of One's Form Is to Live a Death. I Myself, After Existing Some

0 “...to be unaware of one’s form is to live a death. I myself, after existing some twenty years, did not become alive until I discovered my invisibility.” —Ralph Ellison, Invisible Man 1 Contents Cento Against Invisibility….….….….….….….….….….….….….….….….….….….….….…...…1 House Cats….….….….….………………...….….….….….….….….….….….….….….………….2 The Lottery….….….….….………………...….….….….….….….….….….….….….….….…...…4 Erasure Poem….….….….….………………...….….….….….….….….….….….….….….….……6 If you should ever find yourself sitting in the front of a class on racial diversity, ignorance eating its way through the roof of your mouth until it splatters acid across your tastebuds ….….….….…….8 Phan Thị Kim Phúc….….….….….………………...….….….….….….….….….….….….….…….9 curiousity….….….….….…………...…...….….….….….….….….….….….….….….….………..10 Avocado….….….….….…………..…...….….….….….….….….….….….….….….….…………11 Note’s on the Rapist’s Nose.….….………………...…….….….….….….….….….….….….…….12 Pork Chops….….………………...….….….….….….….…….….….….….….….…………...…...13 If Schrödinger Moves In.….….………………...….….….…….….….….….….….….….….…….14 Contrast.….….………………...….….….….….….….….…….….….….….….…………………..15 Vagina Dialogues.….….………………...….….….….….….…...….….….….….….….………….16 Ace for Short.….….………………...….….….….….….….….….…….….….….….……………..17 Prayer for a Dominatrix.….….………………...….….….….….….….….….……….….….….…..19 The Curse.….….………………...….….….….….….….….….….….….….….…...………………20 After the Murder.….….………………...….….….….….….….….….….….….….….…………….21 Separation.….….………………...….….….….….….….….….….….….….….….……..…………23 Retelling.….….………………...….….….….….….….….….….….….….….….……..…………..24 -

Ne-Yo Au Festival Mawazine

Communiqué de presse Rabat, 23 avril 2014 La dernière découverte du rap US à Mawazine Ne-Yo se produira en concert à Rabat le 04 juin 2014 L’Association Maroc Cultures a le plaisir de vous annoncer la venue du chanteur américain Ne-Yo à l’occasion de la 13ème édition du Festival - Mawazine Rythmes du Monde. Ne-Yo se produira mercredi 04 juin 2014 sur la scène de l’OLM-Souissi à Rabat. Dernière découverte du prestigieux label Def Jam, dont l’histoire se confond en grande partie avec celle du rap américain, Ne-Yo (né Shaffer Smith) a hérité d’une voix unique en son genre, inspirée de Stevie Wonder et des plus grands noms de la soul. L’artiste a obtenu en 2008 le Grammy Award du meilleur album contemporain R&B et composé des tubes pour Beyoncé, Rihanna et Britney Spears. Né en 1979 à Los Angeles, Ne-Yo est élevé par une famille de musiciens et se passionne très tôt pour la musique. Ses idoles de l'époque s’appellent Whitney Houston et Michael Jackson. Au cours de cette période, le garçon développe une culture musicale importante, s’essaie au chant, à la composition et à l'écriture. Après plusieurs prestations réussies, Ne-Yo retient l'attention de Def Jam, le label le plus actif de la scène R&B. Avec lui, le chanteur enregistre les singles So Sick , Sexy Love et When You're Mad , qui reçoivent un accueil très favorable dans les clubs de la côte ouest. Ne-Yo sort en 2006 son premier album, In My Own Words , qui se vend à 1 million d’exemplaires. -

Libido Song List 2000

LIBIDO SONG LIST 2000 - Now Ain’t It Fun (Paramore) All Of Me (John Legend) American Boy (Estelle & Kanye West) Bartender (T-Pain & Akon) Because Of You (Ne-Yo) Birthday (Katy Perry) Blame It (Jamie Foxx & T-Pain) Blurred Lines (Robin Thicke) Break Your Heart (Taio Cruz) Burn (Ellie Goulding) Can’t Hold Us (Macklemore) California Gurls (Katy Perry) Champagne Life (Ne-Yo) Closer (Ne-Yo) Counting Stars (OneRepublic) Crazy In Love (Beyonce) DJ Got Us Falling In Love (Usher) Diamonds (Rihanna) Die Young (Ke$ha) Don’t Worry Child (Swedish House Mafia) Dynamite (Taio Cruz) Fancy (Iggy Azalea) Feel Again (OneRepublic) Feel So Close (Calvin Harris) Fine China (Chris Brown) Forget You (Cee-Lo) Get Lucky (Daft Punk & Pharrell) Give Me Everything (Tonight) (Ne-Yo & Pitbull) Gold Digger (Kanye West) Good Feeling (Flo Rida) Good Life (OneRepublic) Happy (Pharrell Williams) Hey Brother (Avicii) Hey Ya (Outkast) Hold On, We’re Going Home (Drake) I Gotta Feeling (Black Eyed Peas) I Just Wanna Love U (Give It To Me) (Jay-Z) I Need Your Love (Calvin Harris) Ignition Remix (R. Kelly) I’m In Miami Trick (LMFAO) In The Club (50 Cent) Just Dance (Lady Gaga) Just The Way You Are (Bruno Mars) Let Me Love You (Ne-Yo) Let’s Get It Started (Black Eyed Peas) Locked Out Of Heaven (Bruno Mars) Love At First Sight (Kylie Minogue) Low (Flo-Rida & T-Pain) Meet Me Halfway (Black Eyed Peas) Moves Like Jagger (Maroon 5 feat. Christina Aguilera) More (Usher) Nothin’ On You (B.o.B. feat Bruno Mars) OMG (Usher feat Will.i.am) Party Rock Anthem (LMFAO) Please Don’t Stop the Music (Rihanna) Pumped Up Kicks (Foster The People) Raise Your Glass (Pink) Rolling In The Deep (Adele) Royals (Lorde) Rude Boy (Rihanna) Safe & Sound (Capital Cities) Say it Right (Nelly Furtado) Scream & Shout (Will.i.am & Britney Spears) Sexy & I Know It (LMFAO) Sexy Chick (Akon & David Guetta) Sexy Love (Ne-Yo) SexyBack (Justin Timberlake) Set Fire To The Rain (Adele) Starships (Nicki Minaj) Stay The Night (Zedd ft. -

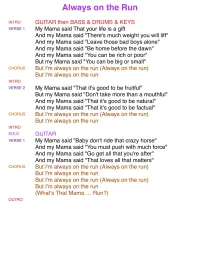

Always on the Run

Always on the Run INTRO GUITAR then BASS & DRUMS & KEYS VERSE 1 My Mama said That your life is a gift And my Mama said "There's much weight you will lift" And my Mama said "Leave those bad boys alone" And my Mama said "Be home before the dawn" And my Mama said "You can be rich or poor" But my Mama said "You can be big or small" cuonus But I'm always on the run (Always on the run) But I'm always on the run INTRO VERSE 2 My Mama said "That it's good to be fruitful" But my Mama said "Don't take more than a mouthful" And my Mama said "That it's good to be natural" And my Mama said "That it's good to be factual" cuonus But I'm always on the run (Always on the run) But I'm always on the run INTRO SOLO GUITAR VERSE 1 My Mama said "Baby don't ride that crazy horse" And my Mama said "You must push with much force" And my Mama said "Go get all that you're after" And my Mama said "That loves all that matters" caonus But I'm always on the run (Always on the run) But I'm always on the run But I'm always on the run (Always on the run) But I'm always on the run (What's That Mama ... Run?) OUTRO Always on the Run INTRO I Em I I I I I I I Em I I I I I I VERSE 1 I Em I I I I I I I Em I I I I I Em I I I I I My Mama said That your life is a gift And my Mama said "There's much weight you will lift" And my Mama said "Leave those bad boys alone" And my Mama said "Be home before the dawn" And my Mama said "You can be rich or poor" But my Mama said "You can be big or small" cuonus I G A I Em I G A I Em I But I'm always on the run (Always on the run) But I'm always -

Listen up LISTEN up Album of the Week, Notables 6D

USA TODAY 8D LIFE TUESDAY, MARCH 18, 2014 More Listen Up LISTEN UP Album of the week, notables 6D SONG OF THE WEEK THE PLAYLIST USA TODAY music critic Brian Mansfield highlights 10 intriguing tracks discovered during the week’s listening. ‘Fallinlove2nite,’ Lanterns Australia’s biggest hit of Catch When this Katy Perry- Prince, Deschanel Birds of Tokyo 2013 is starting to shine Allie X endorsed L.A.-Toronto pop through here, with a songstress sings, “Wait Prince performed this chiming keyboard hook until I catch my breath,” song with Zooey Descha- and an anthem’s chorus. she may take yours. nel on New Girl after Gimme Thrash metal collides with Say You’ll Just call her Icy Spice. the Super Bowl, and Chocolate!! J-pop super-cuteness, Be There Danish singer MØ reworks Babymetal resulting in this girl trio’s MØ the Spice Girls’ follow-up the full version is even mind-blowingly catchy to Wannabe with a chilly better. With its dynamite musical hybrid. electro-pop groove. horn chart, synthesizer Mystery Man A burst of feedback Kiss Me Dashboard Confessional’s solo and Prince’s flirtiest The Strypes heralds a frenetic, Darling Chris Carrabba brings falsetto all over a house- Yardbirds-style rave-up Twin Forks a brighter acoustic tone disco beat, this should from this Irish teen quar- to this band but still wears tet’s Snapshot, out today. his heart on his sleeve. make fans of His Purple Highness’ commercial I Wanna With chopped-up keys, The Secret Nail’s stoically sung love Get Better pop-up vocal choirs and David Nail triangle ends with one of heyday fall hard. -

J Lo's Performance in Rabat Provokes Furore

22 June 12, 2015 Culture J Lo’s performance in Rabat provokes furore Saad Guerraoui said Aftati. Another PJD member, Khalid Rahmouni, expressed dis- gust at what he watched on 2M and Rabat called on Khalfi, as the one respon- sible for media policy, to resign. sexually charged per- However, PJD MP Abdeslam Bal- formance by pop diva laji told The Arab Weekly that Khalfi Jennifer Lopez at the does not have authority over public Mawazine music festival TV channels. in Rabat prompted mem- “It is the responsibility of the bersA of the ruling Islamist Justice High Authority of Audiovisual and Development Party (PJD) to call Communication (HACA) to investi- for the resignation of Communica- gate the matter following the min- tions Minister Mustapha el-Khalfi. ister’s request,” said Ballaji who Lopez, 45 and a popular Ameri- was the first MP from PJD’s parlia- can performer, opened the 14th mentary team to ask Khalfi for an Mawazine festival on May 30th, explanation for the concert. performing a nearly two-hour In a message posted on his Fa- long concert for a record crowd of cebook page, Khalfi, who is also 160,000 while millions watched on the government spokesman, an- state-owned television channel 2M. nounced that HACA and the ethics The glamorous New York-born committee of 2M would be inves- singer showcased scanty costumes tigated. Ballaji stressed that broad- and provocative poses as she casting the US singer’s suggestive donned seven different outfits, -in dance routine on a public TV chan- cluding a white leotard, during her nel was against Morocco’s constitu- performance, which was slammed tion, values and media ethics. -

Nostalgias in Modern Tunisia Dissertation

Images of the Past: Nostalgias in Modern Tunisia Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By David M. Bond, M.A. Graduate Program in Near Eastern Languages and Cultures The Ohio State University 2017 Dissertation Committee: Sabra J. Webber, Advisor Johanna Sellman Philip Armstrong Copyrighted by David Bond 2017 Abstract The construction of stories about identity, origins, history and community is central in the process of national identity formation: to mould a national identity – a sense of unity with others belonging to the same nation – it is necessary to have an understanding of oneself as located in a temporally extended narrative which can be remembered and recalled. Amid the “memory boom” of recent decades, “memory” is used to cover a variety of social practices, sometimes at the expense of the nuance and texture of history and politics. The result can be an elision of the ways in which memories are constructed through acts of manipulation and the play of power. This dissertation examines practices and practitioners of nostalgia in a particular context, that of Tunisia and the Mediterranean region during the twentieth and early twenty-first centuries. Using a variety of historical and ethnographical sources I show how multifaceted nostalgia was a feature of the colonial situation in Tunisia notably in the period after the First World War. In the postcolonial period I explore continuities with the colonial period and the uses of nostalgia as a means of contestation when other possibilities are limited. -

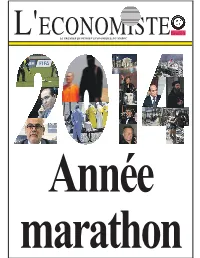

UNE RETROSPECTIVE 2014-A.Indd

Système de Management de la Qualité certifié ISO 9001 version 2008 par BUREAU VERITAS MAROC LE PREMIER QUOTIDIEN ECONOMIQUE DU MAROC Année marathon II RétRospective L’année où la diplomatie • Tournées royales d’envergure construite avec un montant de 330 mil- lions de DH. Les champs de partenariats ont également compris d’autres secteurs • Le capital immatériel fait son comme les finances, les énergies renou- velables, les infrastructures, le transport, entrée dans l’évaluation de la l’agroalimentaire, les mines, l’habitat… richesse du pays L’impact de cette tournée a été retentis- sant en termes de perception du Maroc dans le continent. En peu de temps, le • Appel à une rupture avec les Souverain a construit une image charis- matique en Afrique. La dynamique de la privilèges et l’économie de rente diplomatie royale a permis un plus grand au Sahara rapprochement avec certains Etats du Sahel, comme le Mali, qui n’étaient pas considérés traditionnellement comme des 2014 est décidément l’année bastions acquis au Maroc. Aujourd’hui, de la consécration de l’orientation afri- le renforcement du partenariat avec ces caine du Maroc. La tournée royale dans Etats se base sur une logique de com- la région, durant les premiers mois de plémentarité. Ces Etats ont demandé de cette année, a montré l’engagement du profiter de l’expertise marocaine dans Royaume en faveur du développement de plusieurs domaines, notamment dans la la coopération Sud-Sud. Le pays ne s’est promotion des ressources humaines, mais pas contenté des beaux discours, mais surtout dans l’encadrement religieux. -

NZIFF19 Christchurch WEB.Pdf

CHRISTCHURCH 8 – 25 AUGUST 2019 TIMARU 15 – 25 AUGUST 2019 NZIFF.CO.NZ NZIFF0619_Christchurch-1.indd 1 3/07/19 1:40 PM NZIFF0619_Christchurch-1.indd 2 3/07/19 1:40 PM 43rd Christchurch International Film Festival Presented by New Zealand Film Festival Trust under the distinguished patronage of Her Excellency The Right Honourable Dame Patsy Reddy, Governor-General of New Zealand ISAAC THEATRE ROYAL LUMIÈRE CINEMAS MOVIE MAX DIGITAL PROUDLY SUPPORTED BY General Manager: Sharon Byrne Programmer: Sandra Reid Programme Manager: Michael McDonnell Assistant to the General Manager: Caroline Palmer Communications Manager: Melissa Booth Publicists (Christchurch): Jo Scott, Tanya Jephson Festival Host (Christchurch): Nick Paris Publicist: Sally Woodfield Animation NOW! Programmer: Malcolm Turner All Ages Programmer: Nic Marshall Incredibly Strange Programmer: Anthony Timpson Publications Manager: Tim Wong Programme Consultant: Chris Matthews Content Manager: Ina Kinski Content Assistant: Lauri Korpela Technical Adviser: Ian Freer Online Content Coordinator: Sanja Maric Audience Development Coordinator: Emma Carter Guest Coordinator: Lauren Day Social Media Coordinator: David Oxenbridge Communications Assistant: Lynnaire MacDonald Communications Assistant (Auckland): Camila Araos Elevancini Online Social Assistant: Bradley Pratt Festival Accounts: Alan Collins Festival Interns: Erin Rogatski (Auckland) Jessica Hof (Wellington) Publication Design: Ocean Design Group Publication Production: Greg Simpson Cover Design: Blair Mainwaring Cover Illustration: -

Karaoke Mietsystem Songlist

Karaoke Mietsystem Songlist Ein Karaokesystem der Firma Showtronic Solutions AG in Zusammenarbeit mit Karafun. Karaoke-Katalog Update vom: 13/10/2020 Singen Sie online auf www.karafun.de Gesamter Katalog TOP 50 Shallow - A Star is Born Take Me Home, Country Roads - John Denver Skandal im Sperrbezirk - Spider Murphy Gang Griechischer Wein - Udo Jürgens Verdammt, Ich Lieb' Dich - Matthias Reim Dancing Queen - ABBA Dance Monkey - Tones and I Breaking Free - High School Musical In The Ghetto - Elvis Presley Angels - Robbie Williams Hulapalu - Andreas Gabalier Someone Like You - Adele 99 Luftballons - Nena Tage wie diese - Die Toten Hosen Ring of Fire - Johnny Cash Lemon Tree - Fool's Garden Ohne Dich (schlaf' ich heut' nacht nicht ein) - You Are the Reason - Calum Scott Perfect - Ed Sheeran Münchener Freiheit Stand by Me - Ben E. King Im Wagen Vor Mir - Henry Valentino And Uschi Let It Go - Idina Menzel Can You Feel The Love Tonight - The Lion King Atemlos durch die Nacht - Helene Fischer Roller - Apache 207 Someone You Loved - Lewis Capaldi I Want It That Way - Backstreet Boys Über Sieben Brücken Musst Du Gehn - Peter Maffay Summer Of '69 - Bryan Adams Cordula grün - Die Draufgänger Tequila - The Champs ...Baby One More Time - Britney Spears All of Me - John Legend Barbie Girl - Aqua Chasing Cars - Snow Patrol My Way - Frank Sinatra Hallelujah - Alexandra Burke Aber Bitte Mit Sahne - Udo Jürgens Bohemian Rhapsody - Queen Wannabe - Spice Girls Schrei nach Liebe - Die Ärzte Can't Help Falling In Love - Elvis Presley Country Roads - Hermes House Band Westerland - Die Ärzte Warum hast du nicht nein gesagt - Roland Kaiser Ich war noch niemals in New York - Ich War Noch Marmor, Stein Und Eisen Bricht - Drafi Deutscher Zombie - The Cranberries Niemals In New York Ich wollte nie erwachsen sein (Nessajas Lied) - Don't Stop Believing - Journey EXPLICIT Kann Texte enthalten, die nicht für Kinder und Jugendliche geeignet sind.