Why Marx Was Right Why Marx Was Right

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pink Floyd and Philosophy

Table of Contents Popular Culture and Philosophy Series Editor: George A. Reisch Title Page Pink Floyd: From Pompeii to Philosophy Pink Floyd in Popular Culture Chapter 1 - “I Hate Pink Floyd,” and other Fashion Mistakes of the 1960s, 70s, ... The Four Lads from CambridgeFrom Waffling to MeddlingThe Crazy DiamondWish You Weren’t HereDoes Johnny Rotten Still Hate Pink Floyd? Chapter 2 - Life and Death on The Dub Side of the Moon Side OneSide TwoRasta ReasoningOn Rasta Time“A New Broom Sweeps Clean, but an Old Broom Knows Every Corner” Chapter 3 - Dark and Infinite Goodbye Blue SkyNobody HomeBricks in the WallWe Don’t Need No InterpretationFeelings of an Almost Human Nature Chapter 4 - Pigs Training Dogs to Exploit Sheep: Animals as a Beast Fable Dystopia The Dog-Eat-Dog MarketplacePigs in the WhitehouseSheepish ExploitationCaring Dogs Watching Flying Pigs Chapter 5 - Exploring the Dark Side of the Rainbow Major SynchronizationsDesign or Chance?Synchronizations and SynchronicityApophenia and ParadigmsThematic Synchronicity Chapter 6 - Mashups and Mixups : Pink Floyd as Cinema Defining Cinematic MusicMusic Videos and Music FilmsMashups and Sync UpsIn the End, It’s Only Round and Round (and Round) Alienation (Several Different Ones) Chapter 7 - Dragged Down by the Stone: Pink Floyd, Alienation, and the ... Wish You Were . ConnectedWhen the World You’re in Starts Playing Different TunesDon’t Be Afraid to CareDon’t Sit DownTime, Finitude, and DeathMoneyAny Colour of Us and Them You LikeArtists and Crazy DiamondsThis One’s PinkWe Don’t 2 Need No Indoctrination Chapter 8 - Roger Waters : Artist of the Absurd (C)amused to DeathThat Fat Old SunPrisms and DiamondsWelcome to the ZooThe Pros and Cons of AudiencesAlienation inside the WallWould You Help Me to Carry the Stone? Chapter 9 - Theodor Adorno, Pink Floyd, and the Psychedelics of Alienation Part I: Interstellar OverdriveIt’s Alright, We Told You What to DreamCan the Machine Be Fixed?Arnold Schoenberg had a Strraaaange . -

The Chhandogya Upanishad

TTHEHE CCHHANDOGYAHHANDOGYA UUPANISHADPANISHAD by Swami Krishnananda The Divine Life Society Sivananda Ashram, Rishikesh, India (Internet Edition: For free distribution only) Website: www.swami-krishnananda.org CONTENTS PUBLISHERS’ PREFACE 5 CHAPTER I: VAISHVANARA-VIDYA 7 The Panchagni-Vidya 7 The Course of the Soul After Death 8 Vaishvanara, The Universal Self 28 Heaven as the Head of the Universal Self 31 The Sun as the Eye of the Universal Self 32 Air as the Breath of the Universal Self 33 Space as the Body of the Universal Self 33 Water as the Lower Belly of the Universal Self 33 The Earth as the Feet of the Universal Self 34 The Self as the Universal Whole 34 The Five Pranas 37 The Need for Knowledge is Stressed 39 Conclusion 40 CHAPTER II 43 Section 1: Preliminary 43 Section 2: The Primacy of Being 46 Section 3: Threefold Development 51 Section 4: Threefold Development (Contd.) 53 Section 5: Illustrations of the Threefold Nature 56 Section 6: Further Illustrations 57 Section 7: Importance of Physical Needs 58 Section 8: Concerning Sleep, Hunger, Thirst and Dying 60 Section 9: The Indwelling Spirit 65 Section 10: The Indwelling Spirit (Contd.) 67 Section 11: The Indwelling Spirit (Contd.) 68 Section 12: The Indwelling Spirit (Contd.) 69 Section 13: The Indwelling Spirit (Contd.) 71 Section 14: The Indwelling Spirit (Contd.) 73 Section 15: The Indwelling Spirit (Contd.) 76 Section 16: The Indwelling Spirit (Contd.) 78 CHAPTER III: SANATKUMARA’S INSTRUCTIONS ON BHUMA-VIDYA 81 The Chhandogya Upanishad by Swami Krishnananda 2 Section -

Pocket Songs Karaoke Song Book

Pocket Songs/Just Tracks Songs by Artist Karaoke Shack Song Books Title DiscID Title DiscID 10,000 Maniacs 98 Degrees Because The Night JTG069-01 My Everything PS1520-12 110 Degrees In The Shade Why (Are We Still Friends) PS1566-17 Is It Really Me PS2003-2-18 98 Degrees (Wvocal) 110 Degrees In The Shade (Wvocal) Because Of You PS1455-07 Is It Really Me PS2003-2-07 Give Me Just One Night (Una Noche) PS1506-02 112 Hardest Thing, The PS1414-04 Dance With Me PS1544-13 I Do (Cherish You) PS1447-03 112 (Wvocal) My Everything PS1520-03 Dance With Me PS1544-05 Why (Are We Still Friends) PS1566-08 3 Doors Down A3 Kryptonite JTG366-13 Woke Up This Morning JTG192-17 Kryptonite PS1507-18 Woke Up This Morning PS1483-18 Kryptonite PS6008-1-15 A3 (Wvocal) Kryptonite (Wbgv) PS6008-1-09 Woke Up This Morning PS1483-09 Loser PS1539-12 Aaliyah 3 Doors Down (Wvocal) Are You That Somebody PS1313-15 Kryptonite PS1507-09 At Your Best PS1302-11 Kryptonite PS6008-1-03 Back And Forth PS1302-10 Loser PS1539-04 Journey To The Past JTG114-10 3 Of Hearts Journey To The Past PS1302-12 Love Is Enough PS1548-17 Journey To The Past (No Graphics) PS1268-13 3 Of Hearts (Wvocal) Miss You PS1596-14 Love Is Enough PS1548-07 More Than A Woman JTG301-11 4Him More Than A Woman PS1565-14 Basics Of Life, The (High Voice) PS1646-1-08 One I Gave My Heart To, The JTG118-06 Basics Of Life, The (Low Voice) PS1646-2-08 One I Gave My Heart To, The JTG159-07 4Him (Wvocal) One I Gave My Heart To, The PS1302-09 Basics Of Life, The (High Voice) PS1646-1-01 One I Gave My Heart To, The PS1306-10 -

The True Name, Vol 2

The True Name, Vol 2 Talks given from 1/12/74 to 10/12/74 Original in Hindi 10 Chapters Year published: 1993 Original series title "Ek Omkar Satnam" The True Name, Vol 2 Chapter #1 Chapter title: Fear Is A Beggar 1 December 1974 am in Chuang Tzu Auditorium THERE IS NO END TO HIS VIRTUES, NOR TO THEIR NARRATION. THERE IS NO END TO HIS WORKS AND HIS BOUNTY, AND ENDLESS WHAT HE SEES AND HEARS. THERE IS NO KNOWING THE SECRETS OF HIS MIND; THERE IS NO BEGINNING OR END TO IT. SO MANY STRUGGLE TO KNOW HIS DEPTH, BUT NONE HAS EVER ACHIEVED IT. NO ONE HAS EVER KNOWN HIS LIMITS; THE FURTHER YOU LOOK, THE FURTHER BEYOND HE LIES. THE LORD IS GREAT. HIS PLACE IS HIGH, AND HIGHER EVEN IS HIS NAME. NANAK SAYS: ONE ONLY KNOWS HIS GREATNESS WHEN RAISED TO HIS HEIGHTS, BY FALLING UNDER THE GLANCE OF HIS ALL-COMPASSIONATE GRACE. HIS COMPASSION IS BEYOND ALL DESCRIPTION. THE LORD'S GIFTS ARE SO GREAT HE EXPECTS NOTHING IN RETURN. HOWEVER GREAT A HERO OR WARRIOR, MAN KEEPS ON BEGGING. IT IS DIFFICULT TO CONCEIVE THE COUNTLESS NUMBERS WHO GO ON ASKING. THEY INDULGE THEMSELVES IN DESIRES AND DISSIPATE THEIR LIVES. AND OTHERS RECEIVE, YET DENY IT. THEY GO ON SUFFERING FROM THEIR HUNGER, YET WILL NOT TAKE TO REMEMBRANCE O LORD, THESE TOO ARE YOUR GIFTS. YOUR ORDER ALONE GIVES FREEDOM OR BONDAGE. NOBODY CAN DEBATE THIS FACT. HE WHO INDULGES IN USELESS BABBLE REALIZES HIS FOLLY WHEN STRUCK IN THE FACE. -

2 Column Indented

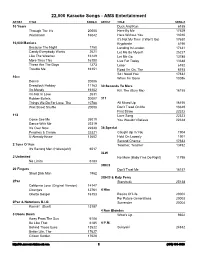

22,000 Karaoke Songs - AMS Entertainment ARTIST TITLE SONG # ARTIST TITLE SONG # 10 Years Duck And Run 6188 Through The Iris 20005 Here By Me 17629 Wasteland 16042 Here Without You 13010 It's Not My Time (I Won't Go) 17630 10,000 Maniacs Kryptonite 6190 Because The Night 1750 Landing In London 17631 Candy Everybody Wants 2621 Let Me Be Myself 25227 Like The Weather 16149 Let Me Go 13785 More Than This 16150 Live For Today 13648 These Are The Days 1273 Loser 6192 Trouble Me 16151 Road I'm On, The 6193 So I Need You 17632 10cc When I'm Gone 13086 Donna 20006 Dreadlock Holiday 11163 30 Seconds To Mars I'm Mandy 16152 Kill, The (Bury Me) 16155 I'm Not In Love 2631 Rubber Bullets 20007 311 Things We Do For Love, The 10788 All Mixed Up 16156 Wall Street Shuffle 20008 Don't Tread On Me 13649 First Straw 22322 112 Love Song 22323 Come See Me 25019 You Wouldn't Believe 22324 Dance With Me 22319 It's Over Now 22320 38 Special Peaches & Cream 22321 Caught Up In You 1904 U Already Know 13602 Hold On Loosely 1901 Second Chance 17633 2 Tons O' Fun Teacher, Teacher 13492 It's Raining Men (Hallelujah!) 6017 3LW 2 Unlimited No More (Baby I'ma Do Right) 11795 No Limits 6183 3Oh!3 20 Fingers Don't Trust Me 16157 Short Dick Man 1962 3OH!3 & Katy Perry 2Pac Starstrukk 25138 California Love (Original Version) 14147 Changes 12761 4 Him Ghetto Gospel 16153 Basics Of Life 20002 For Future Generations 20003 2Pac & Notorious B.I.G. -

Durham E-Theses

Durham E-Theses Christology in the writings of C. S. Lewis: a Lutheran's evaluation Mueller, Steven Paul How to cite: Mueller, Steven Paul (1997) Christology in the writings of C. S. Lewis: a Lutheran's evaluation, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/4756/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk Steven Paul Mueller Christology in the Writings of C. S. Lewis: a Lutheran's Evaluation Ph.D. thesis, University of Durham, 1997 Abstract This thesis seeks to ascertain and evaluate the Christological content and method of C. S. Lewis as seen throughout his writings. The continuing popularity and sales of his works demonstrate his effectiveness. Lewis referred to his Christian writings as "translations" that expressed Christian doctrine in a manner that was accessible and understandable to the laity. -

Songs by Artist

Songs by Artist Title Title Title Title - Dolly Parton & Kenny Rogers 3 Dog Night 38 Special 50 Cents Islands In The Stream Celebrate Second Chance Just A Lil Bit 10 Years Easy To Be Hard 3LW 5ive Beautiful Eli's Comin' No More (Baby I'm A Do Right) Keep On Movin' Through The Iris Family Of Man No More (Baby I'ma Do Right) 5th Dimension Wasteland Joy To The World 3Oh!3 Aquarius (Let The Sun Shine In) 10,000 Maniacs Joy To The World Dont Trust Me Aquarius Let The Sunshine Because The Night Just An Old Fashioned Love Song 3sl One Less Bell To Answer Candy Everybody Wants Liar Take It Easy Wedding Bell Blues Like The Weather Mama Told Me (Not To Come) 3t 6. Red Hot Chilie Peppers More Than This Never Been To Spain Anything The Zepher Song Trouble Me One Tease Me 702 10cc Out In The Country 4 Non Blondes Steelo DONNA Pieces Of April Whats Going On Where My Girls At Dreadlock Holiday Shambala Whats Up Where My Girls At (Vocals Right I'm Mandy Show Must Go On What's Up Channel Only) Im Not In Love 3 Doors Down What's Up 1 8. Wet Wet Wet I'm Not In Love Away From The Sun 4 Runner Love Is All Around2 Rubber Bullets Be Like That That Was Him 911 The Things We Do For Love Behind Those Eyes 411 A Little Bit More Wall Street Shuffle Citizen Soldier Dumb All I Want Is You 112 Duck And Run On My Knees How Do You Want Me To Love You Dance With Me Here By Me 411 & Ghostface More Than A Woman U Already Know Here Without You On My Knees Party People (Friday Night) 1910 Fruitgum Co. -

2 Column Indented

Music By Bonnie 25,000 Karaoke Songs ARTIST TITLE SONG # ARTIST TITLE SONG # 10 Years 20 Fingers Actions & Motives 29768 Short Dick Man 1962 Beautiful 29769 Drug Of Choice 29770 3 Doors Down Fix Me 29771 Away From The Sun 6184 Shoot It Out 29772 Be Like That 6185 Through The Iris 20005 Behind Those Eyes 13522 Wasteland 16042 Better Life, The 17627 Citizen Soldier 17628 10,000 Maniacs Duck And Run 6188 Because The Night 1750 Every Time You Go 25704 Candy Everybody Wants 2621 Here By Me 17629 Like The Weather 16149 Here Without You 13010 More Than This 16150 It's Not My Time (I Won't Go) 17630 These Are The Days 1273 Kryptonite 6190 Trouble Me 16151 Landing In London 17631 100 Proof Aged In Soul Let Me Be Myself 25227 Somebody's Been Sleeping In My Bed 27746 Let Me Go 13785 Live For Today 13648 10cc Loser 6192 Donna 20006 Road I'm On, The 6193 Dreadlock Holiday 11163 So I Need You 17632 I'm Mandy 16152 When I'm Gone 13086 I'm Not In Love 2631 When You're Young 25705 Rubber Bullets 20007 Things We Do For Love, The 10788 3 Inches Of Blood Wall Street Shuffle 20008 Deadly Sinners 27748 112 30 Seconds To Mars Come See Me 25019 Closer To The Edge 26358 Dance With Me 22319 Kill, The (Bury Me) 16155 It's Over Now 22320 Kings And Queens 26359 Peaches & Cream 22321 311 U Already Know 13602 All Mixed Up 16156 12 Stones Don't Tread On Me 13649 We Are One 27248 Down 27749 First Straw 22322 1975, The Love Song 22323 Love Me 29773 You Wouldn't Believe 22324 Sound, The 29774 UGH! 29775 36 Crazyfists Bloodwork 29776 2 Chainz Destroy The Map 29777 Spend It 25701 Great Descent, The 29778 2 Live Crew Midnight Swim 29779 Do Wah Diddy 25702 Slit Wrist Theory 29780 Me So Horny 27747 38 Special We Want Some PuXXy 25703 Caught Up In You 1904 2 Pistols (ft. -

Perelandra a Novel

Perelandra A novel C. S. Lewis Fellow of Magdalen College, Oxford S AMIZDAT QUÉBEC Based on the public domain etext provided by “Harry Kruiswijk”. Perelandra by C. S. Lewis. Date of first publication: 1943 at The Bodley Head. Samizdat, November 2015 (public domain under Canadian copy- right law) Fonts: ITC Garamond BalaCynwyd Disclaimer This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost. Copyright laws in your country also govern what you can do with this work. Copyright laws in most countries are in a constant state of flux. If you are outside Canada, check the laws of your country before downloading, copying, displaying, performing, distributing or creating derivative works based on this Samizdat Ebook. Samizdat makes no claims regarding the copyright status of any work in any country outside Canada. TO S OME L ADIE S AT W ANTAGE Contents Preface 1 Chapter One 2 Chapter Two 12 Chapter Three 22 Chapter Four 33 Chapter Five 45 Chapter Six 56 Chapter Seven 68 Chapter Eight 79 Chapter Nine 87 Chapter Ten 102 Chapter Eleven 115 Chapter Twelve 125 Chapter Thirteen 134 Chapter Fourteen 144 Chapter Fifteen 154 Chapter Sixteen 164 Chapter Seventeen 173 Preface HIS story can be read by itself but is also a sequel to Out of the T Silent Planet in which some account was given of Ransom’s adventures in Mars — or, as its inhabitants call it, Malacandra. All the human characters in this book are purely fictitious and none of them is allegorical. C.S.L. Chapter One s I left the railway station at Worchester and set out on the A three-mile walk to Ransom’s cottage, I reflected that no one on that platform could possibly guess the truth about the man I was going to visit. -

The Decameron. Giovanni Boccacio

Coradella Collegiate Bookshelf Editions. The Decameron. Giovanni Boccacio. Open Contents Purchase the entire Coradella Collegiate Bookshelf on CD at http://collegebookshelf.net Purchase the entire Coradella Collegiate Bookshelf on CD at Giovanni Boccaccio. The Decameron. http://collegebookshelf.net Sulmona and Giovanni Barrili, and the theologian Dionigi da San Sepolcro. About the author In the 1330s Boccaccio also became a father, two illegitimate children of his were born in this time, Mario and Giulio. Giovanni Boccaccio (June 16, 1313 In Naples Boccaccio began what he considered his true vocation, poetry. - December 21, 1375) was a Florentine Works produced in this period include Filostrato (the source for Chaucer’s author and poet, the greatest of Petrarch’s Troilus and Criseyde), Teseida (ditto the Knight’s Tale), Filocolo a prose version disciples, an important Renaissance hu- of an existing French romance, and La caccia di Diana a poem in octave manist in his own right and author of a rhyme listing Neopolitan women. number of notable works including On Boccaccio returned to Florence in early 1341, avoiding the plague in that Famous Women, the Decameron and his city of 1340 but also missing the visit of Petrarch to Naples in 1341. He had poems in the vernacular. left Naples due to tensions between the Angevin king and Florence, his The exact details of his birth are uncertain. He was almost certainly a father had returned to Florence in 1338 and bankruptcy and the death of his bastard, the son of a Florentine banker and an unknown woman. An early wife a little later. -

NDC Meditations 2020

1 SUMMARY PRESENTATION OF PREPARATION PACK ................................................................................................. 4 HOW TO LEAD A ROSARY MEDITATION .................................................................................................. 8 PRESENTATION OF THE « GUARDIAN ANGELS » CHAPTER AT THE PILGRIMAGE TO CHARTRES .......... 10 A WORD FROM THE CHAPLAIN GENERAL ............................................................................................. 12 PARTIE I : ADDRESS TO CHAPTER LEADERS ........................................................................................... 14 PART II: THEMATIC MEDITATIONS ........................................................................................................ 17 SATURDAY: CONVERSION ...................................................................................................................... 18 WHO ARE THE ANGELS? MEDITATION 1 ............................................................................................... 19 SAINT MICHAEL ARCHANGEL MÉDITATION 2 ....................................................................................... 22 CONVERSION THE FIRST STEP OF RETURNING TO GOD MEDITATION 3 ............................................... 26 SUNDAY: SPIRITUAL BATTLE .................................................................................................................. 29 SAINT RAPHAEL ARCHANGEL MEDITATION 4 ....................................................................................... 30 SPIRITUAL -

A+ Entertainment Song List by Title

A+ Entertainment Song List by Title Complete Songs listed by TITLE TITLE ARTIST 4 AM Fiona, Melanie 3 Spears, Britney 7 Catfish And The Bottlemen 22 Swift, Taylor 24 Jem 45 Gaslight Anthem 360 Hoge, Josh 679 Fetty Wap & Remy Boyz 1901 Phoenix 1973 Blunt, James 1979 Smashing Pumpkins 1985 Bowling For Soup 1999 Prince 7/11 Beyonce #1 Nelly #1 Crush Garbage #Selfie Chainsmokers #Thatpower Will.I.Am & Bieber, Justin (How Could You) Bring Him Home Eamon (I Hate) Everything About You Three Days Grace (I Wanna See You) Push It Baby Paul, Sean & Pretty Ricky (I Wanna See You) Push It Baby Pretty Ricky & Paul, Sean (Kissed You) Good Night Gloriana (Reach Up For The) Sunrise Duran Duran (Take My) Life Away Default (You Want To) Make A Memory Bon Jovi 0 To 100/The Catch Up Drake 1 Thing Amerie 1, 2 Step (Remix) Ciara & Elliott, Missy 1, 2 Step (Remix) Elliott, Missy & Ciara 1,2 Step Ciara & Elliott, Missy 1,2 Step Elliott, Missy & Ciara 1,2,3,4 Feist 1,2,3,4 Plain White T's 10 Out Of 10 Lou, Louchie & Michie One 10 Out Of 10 Lou, Louchie & Michie One 10 Out Of 10 Michie One & Lou, Louchie 10 Out Of 10 Michie One & Lou, Louchie 100 Girls Stroke 9 100 Years Five For Fighting 100% Pure Love Crystal Waters 11 Blocks Wrabel 16 @ War Pasian, Karina 18 Days Saving Abel 19 Somethin' Wills, Mark 19-2000 Gorillaz 19-2000 (Remix) Gorillaz 1st Of Tha Month Bone 2 Become 1 Jewel 2 Become 1 Spice Girls 2 Heads Hell, Coleman 2 In The Morning New Kids On The Block 2 Legit To Quit MC Hammer 2 On Tinashe & Schoolboy Q 2 Phones Gates, Kevin 2 Reasons Songz, Trey & T.I.