Slavery Revisited in Penal Plantation Labor

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

BLACK MEN MAKING IT in AMERICA: the Engines of Economic Success for Black Men in America

BLACK MEN MAKING IT IN AMERICA: The Engines of Economic Success for Black Men in America W. Bradford Wilcox, Wendy R. Wang, and Ronald B. Mincy Black Men Making It in America: The Engines of Economic Success for Black Men in America 1 Table of Contents CHAPTER 1: Introduction 4 CHAPTER 2: Black Men Who Have Made It 7 CHAPTER 3: Assessing Conventional Accounts of Black Men’s Success 12 CHAPTER 4: Other Engines of Opportunity for Black Men 16 CHAPTER 5: Conclusion 20 APPENDICES 24 2 Black Men Making It in America: The Engines of Economic Success for Black Men in America EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Over the last decade, much of the racial news and academic research on black men in America has been sobering, if not downright depressing. But negative news isn’t the only story about race or even about black males in the United States. In Black Men Making It in America, we report some good news: • Black men’s economic standing. More than one-in-two black men (57%) have made it into the middle class or higher as adults today, up from 38% in 1960, according to a new analysis of Census data. And the share of black men who are poor has fallen from 41% in 1960 to 18% in 2016. So, a substantial share of black men in America are realizing the American Dream—at least financially—and a clear majority are not poor. • The institutional engines of black men’s success. As expected, higher education and full-time work look like engines of success for black men in America. -

Growth in the U.S. Ex-Felon and Ex-Prisoner Population, 1948 to 2010

GROWTH IN THE U.S. EX-FELON AND EX-PRISONER POPULATION, 1948 TO 2010 Sarah Shannon, Christopher Uggen, MElissa Thompson, Jason Schnittker, and Michael Massoglia Abstract The steep rise in U.S. criminal punishment in recent dEcades has spurred scholarship on the collateral consequences of imprisonment for individuals, familiEs and communities (Pager 2009; WakefiEld and Uggen 2010; Western 2006; Wildeman 2009). WhilE sEveral excEllent studies have estimated the size and social distribution of the former prisoner population (Bonczar and Beck 1997; PEttit and Western 2004), far less is known about the size and scope of thE total ex-felon population beyond prison walls. This paper extends previous national estimates of the U.S. ex-fElon population to 2010 and develops state-level estimates based on demographic life tables (Uggen, Manza and Thompson 2006). The felon population has far-reaching consequences for individuals as well as communities and social institutions, including civic engagEment and community health. 1 GROWTH IN THE U.S. EX-FELON AND EX-PRISONER POPULATION, 1948 TO 2010 As U.S. rates of criminal punishment have increased dramatically over the past 40 years, social scientists have begun to document and explicatE the far-flung consequences of incarceration (see, E.g., WakefiEld and Uggen 2010). As Figure 1 demonstrates, however, the lion’s share of this growth has been among the non-incarcerated population of probationers and parolees who are supervised in their communities. Such trends have important social and dEmographic consequences, as those subject to criminal sanctions facE restrictions on Employment, housing, voting, and welfare recEipt, as well as long- term effects on physical and mental health (Ewald and Uggen 2011; Massoglia 2008; Schnittker and John 2007). -

Prison Abolition and Grounded Justice

Georgetown University Law Center Scholarship @ GEORGETOWN LAW 2015 Prison Abolition and Grounded Justice Allegra M. McLeod Georgetown University Law Center, [email protected] This paper can be downloaded free of charge from: https://scholarship.law.georgetown.edu/facpub/1490 http://ssrn.com/abstract=2625217 62 UCLA L. Rev. 1156-1239 (2015) This open-access article is brought to you by the Georgetown Law Library. Posted with permission of the author. Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.georgetown.edu/facpub Part of the Criminal Law Commons, Criminal Procedure Commons, Criminology Commons, and the Social Control, Law, Crime, and Deviance Commons Prison Abolition and Grounded Justice Allegra M. McLeod EVIEW R ABSTRACT This Article introduces to legal scholarship the first sustained discussion of prison LA LAW LA LAW C abolition and what I will call a “prison abolitionist ethic.” Prisons and punitive policing U produce tremendous brutality, violence, racial stratification, ideological rigidity, despair, and waste. Meanwhile, incarceration and prison-backed policing neither redress nor repair the very sorts of harms they are supposed to address—interpersonal violence, addiction, mental illness, and sexual abuse, among others. Yet despite persistent and increasing recognition of the deep problems that attend U.S. incarceration and prison- backed policing, criminal law scholarship has largely failed to consider how the goals of criminal law—principally deterrence, incapacitation, rehabilitation, and retributive justice—might be pursued by means entirely apart from criminal law enforcement. Abandoning prison-backed punishment and punitive policing remains generally unfathomable. This Article argues that the general reluctance to engage seriously an abolitionist framework represents a failure of moral, legal, and political imagination. -

The California Prisoners Union in Without Freedom of Expression 1971

THE CALIFORNIA A Prisoners Rights Union Publication Sacramento, CA June 1991 Vol. 19, No.2 1971-1991: A History of Fighting For Prisoner's Rights PRU and the Law .\ "The law in its impartial majesty forbids the rich and poor alike from steahng bread and sleeping under bridges." By Michael Snedeker ways been the second type. These categories are not water-tight; the Union or Its volunteers have often tried to Union's Philosophy help individuals, and have also weighed in heavily recently Is the Law a thing to be ad against the explosive growth of mired? In California, laws are imprisonment as the ofiicial solu auctioned off to the interest tion to a host of societal groups that pay the most. Gover· problems. However, groups that nor Wilson was given $760,000 want to abolish prisons or help by California's prison guards to individuals share an indifference run for office; few among us could to the legal structure governing remain unaffected by such a sum prisons, while the Prisoners of money. Inside prison, laws are Union has made this stn lct-ure more like suggestions than fixed its central focus. norms. Still and all, the Bill of The righ ts closest to our hearts Rights has not yet been repealed; are tho e g1raranteed by the First the Prisoners Rights Uh ion has Amendment to the United States alws,ys been interested in and in· Constitut ion, Ilnd Al·ticle 1, sec volved with cha nging or enforc· lions 2 and 3 of the California ing laws. Constitution; the rights t.bat col Our interest arises fro m the ledively make up what has been Union's essential nat u re. -

Prisoner Testimonies of Torture in United States Prisons and Jails

Survivors Speak Prisoner Testimonies of Torture in United States Prisons and Jails A Shadow Report Submitted for the November 2014 Review of the United States by the Committee Against Torture I. Reporting organization The American Friends Service Committee (AFSC) is a Quaker faith based organization that promotes lasting peace with justice, as a practical expression of faith in action. AFSC’s interest in prison reform is strongly influenced by Quaker (Religious Society of Friends) activism addressing prison conditions as informed by the imprisonment of Friends for their beliefs and actions in the 17th and 18th centuries. For over three decades AFSC has spoken out on behalf of prisoners, whose voices are all too frequently silenced. We have received thousands of calls and letters of testimony of an increasingly disturbing nature from prisoners and their families about conditions in prison that fail to honor the Light in each of us. Drawing on continuing spiritual insights and working with people of many backgrounds, we nurture the seeds of change and respect for human life that transform social relations and systems. AFSC works to end mass incarceration, improve conditions for people who are in prison, stop prison privatization, and promote a reconciliation and healing approach to criminal justice issues. Contact Person: Lia Lindsey, Esq. 1822 R St NW; Washington, DC 20009; USA Email: [email protected] +1-202-483-3341 x108 Website: www.afsc.org Acknowledgements This report would not have been possible but for the courageous individuals held in U.S. prisons and jails who rise above the specter of reprisal for sharing testimonies of the abuses they endure. -

State Slavery Sanctioned by the 13Th Amendment

State Slavery sanctioned by the 13th Amendment HISTORY OF PRISON LABOR IN THE UNITED STATES Prison labor has its roots in slavery. After the 1861-1865 Civil War, a system of “hiring out prisoners” was introduced in order to continue the slavery tradition. Freed slaves were charged with not carrying out their sharecropping commitments (cultivating someone else’s land in exchange for part of the harvest) or petty thievery – which were almost never proven –or vagrancy (leaving the plantation in search of better opportunities) and were then “hired out” for cotton picking, working in mines and building railroads. From 1870 until 1910 in the state of Georgia, 88% of hired-out convicts were Black. In Alabama, 93% of “hired-out” miners were Black. In Mississippi, a huge prison farm similar to the old slave plantations replaced the system of hiring out convicts. The notorious Parchman plantation existed until 1972. At least 37 states have legalized the contracting of prison labor by private corporations that mount their operations inside state prisons. The list of such companies contains the cream of U.S. corporate society: IBM, Boeing, Motorola, Microsoft, AT&T, Wireless, Texas Instrument, Dell, Compaq, Honeywell, Hewlett-Packard, Nortel, Lucent Technologies, 3Com, Intel, Northern Telecom, TWA, Nordstrom’s, Revlon, Macy’s, Pierre Cardin, Target Stores, and many more. All of these businesses are excited about the economic boom generation by prison labor. Just between 1980 and 1994, profits went up from $392 million to $1.31 billion. Inmates in state penitentiaries generally receive the minimum wage for their work, but not all; in Colorado, they get about $2 per hour, well under the minimum. -

(UNODC), Handbook for Prison Leaders: a Basic Training Tool

Handbook for prison leaders A basic training tool and curriculum for prison managers based on international standards and norms CRIMINAL JUSTICE HANDBOOK SERIES Cover images: Left and right: ©Photodisc.com, Centre: ©iStockphoto.com/theprint UNITED NATIONS OFFICE ON DRUGS AND CRIME Vienna Handbook for prison leaders A basic training tool and curriculum for prison managers based on international standards and norms CRIMINAL JUSTICE HANDBOOK SERIES UNITED NATIONS New York, 2010 UNITED NATIONS PUBLICATION Sales No. E.10.IV.4 ISBN 978-92-1-130292-9 © United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, March 2010 The designations employed and the presentation of material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. This publication has not been formally edited. Publishing production: UNOV/DM/CMS/EPLS/Electronic Publishing Unit. ii Acknowledgements This Handbook for prison leaders was prepared for the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) by Vivienne Chin, Associate, International Centre for Criminal Law Reform and Criminal Justice Policy, Vancouver, Canada, with the assistance of Robert E. Brown, Yvon Dandurand and Eric McAskill. The Handbook was reviewed by a group of international experts. UNODC wishes to acknowledge the valuable contribution of experts who reviewed this tool and helped finalize it: Elias Carranza, Aggrey Nyapola, Michael Langelaar, and Richard Kuuire. UNODC also wishes to acknowledge the support provided by the Government of Canada. -

Group Dynamics in the Prison Community Morris G

Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology Volume 46 | Issue 5 Article 5 1956 Group Dynamics in the Prison Community Morris G. Caldwell Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.law.northwestern.edu/jclc Part of the Criminal Law Commons, Criminology Commons, and the Criminology and Criminal Justice Commons Recommended Citation Morris G. Caldwell, Group Dynamics in the Prison Community, 46 J. Crim. L. Criminology & Police Sci. 648 (1955-1956) This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Northwestern University School of Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology by an authorized editor of Northwestern University School of Law Scholarly Commons. GROUP DYNAMICS IN THE PRISON COMMUNITY MORRIS G. CALDWELL Dr. Caldwell is Professor of Sociology in the University of Alabama. His "Case Analysis Method for the Personality Study of Offenders" was published in our Volume 45, Number 3 (September-October, 1954) Pp. 291 ff. He was State Director of Cor- rections in Wisconsin from 1939 to 1943, member of the Wisconsin Parole Board during the same period, and National Chairman of the Council on Youth Delin- quency from July 1, 1943 to December 31, 1945. He is Counsel to Human Resources Research Institute for nation-wide studies of adult crime and juvenile delinquency. Jointly with Laurence Foster he published Analysis of Social Problems in February, 1954.-EnrxoR. The thesis upon which this paper is predicated may be briefly stated: A scientific knowledge of the dynamic interrelations existing between social groups within the prison community is indispensable to the prison administrator, warden, deputy warden, heads of prison departments, and other members of the prison staff. -

Promoting a Sustainable Model of Food Justice in America's Prisons Hillary Lyons

Vassar College Digital Window @ Vassar Senior Capstone Projects 2012 Food, Farming, and Freedom : Promoting a Sustainable Model of Food Justice in America's Prisons Hillary Lyons Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalwindow.vassar.edu/senior_capstone Recommended Citation Lyons, Hillary, "Food, Farming, and Freedom : Promoting a Sustainable Model of Food Justice in America's Prisons" (2012). Senior Capstone Projects. 73. http://digitalwindow.vassar.edu/senior_capstone/73 This Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Window @ Vassar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Senior Capstone Projects by an authorized administrator of Digital Window @ Vassar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FOOD, FARMING, AND FREEDOM Promoting a Sustainable Model of Food Justice in America's Prisons BY HILLARY LYONS SENIOR THESIS AMCL 302/03 2012 Lyons, 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ABSTRACT METHODOLOGY I. INTRODUCTION II. PRISON LABOR III. THE TRANSFORMATION OF 21 ST CENTURY AGRICULTURE IV. THE RURAL PRISON BOOM V. THE PRIVATIZATION OF PRISON FOOD VI. CASE STUDY: SA VB OUR PRISON FARMS VII. THE FUTURE OF PRISON FOOD WORKS CITED Lyons, 2 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to thank all of those who contributed to this research project, without whom, this would not have been possible. These are the people who have incited my passions for food justice and prisoners' rights around the common ideal that I present within this paper: the universal right to self-reliance, empowerment, and food security that can someday move us all toward a sustainable future. To Bridget Doherty of the Save Our Prison Farms campaign, thank you for serving as an inspiration of social and environmental advocacy's potential to unite people, and for representing those that have no political voice in a world dominated by corporate power. -

Manufacturing Consent Among Prisoners And

University of Chicago Law School Chicago Unbound Coase-Sandor Working Paper Series in Law and Coase-Sandor Institute for Law and Economics Economics 2011 Making Willing Bodies: Manufacturing Consent among Prisoners and Soldiers, Creating Human Subjects, Patriots, and Everyday Citizens—The University of Chicago Malaria Experiments on Prisoners at Stateville Penitentiary Bernard E. Harcourt Follow this and additional works at: https://chicagounbound.uchicago.edu/law_and_economics Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Bernard E. Harcourt, "Making Willing Bodies: Manufacturing Consent among Prisoners and Soldiers, Creating Human Subjects, Patriots, and Everyday Citizens—The nivU ersity of Chicago Malaria Experiments on Prisoners at Stateville Penitentiary" (John M. Olin This Working Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the Coase-Sandor Institute for Law and Economics at Chicago Unbound. It has been accepted for inclusion in Coase-Sandor Working Paper Series in Law and Economics by an authorized administrator of Chicago Unbound. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CHICAGO JOHN M. OLIN LAW & ECONOMICS WORKING PAPER NO. 544 (2D SERIES) PUBLIC LAW AND LEGAL THEORY WORKING PAPER NO. 341 MAKING WILLING BODIES: MANUFACTURING CONSENT AMONG PRISONERS AND SOLDIERS, CREATING HUMAN SUBJECTS, PATRIOTS AND EVERYDAY CITIZENS Bernard E. Harcourt THE LAW SCHOOL THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO revised May 2011 This paper can be downloaded without charge at the John M. Olin Program in Law and Economics Working Paper Series: http://www.law.uchicago.edu/Lawecon/index.html and at the Public Law and Legal Theory Working Paper Series: http://www.law.uchicago.edu/academics/publiclaw/index.html and The Social Science Research Network Electronic Paper Collection. -

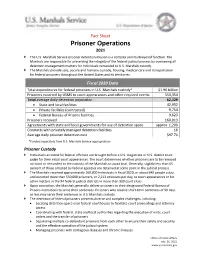

Prisoner Operations Fact Sheet

U .S. Marshals Service Juslic;c. hncgrity. Sc:rvic;c. U.S. Ocp:tnou.:nt of Justice Fact Sheet Prisoner Operations 2021 The U.S. Marshals Service prisoner detention mission is a complex and multilayered function. The Marshals are responsible for preserving the integrity of the federal judicial process by overseeing all detention management matters for individuals remanded to U.S. Marshals custody. The Marshals provide safe, secure and humane custody, housing, medical care and transportation for federal prisoners throughout the United States and its territories. Fiscal 2020 Data Total expenditures for federal prisoners in U.S. Marshals custody* $1.96 billion Prisoners escorted by USMS to court appearances and other required events 553,354 Total average daily detention population 62,329 • State and local facilities 42,952 • Private facilities (contracted) 9,754 • Federal Bureau of Prisons facilities 9,623 Prisoners received 160,013 Agreements with state and local governments for use of detention space approx. 1,200 Contracts with privately managed detention facilities 16 Average daily prisoner detention cost $97.70 *Funded separately from U.S. Marshals Service appropriation Prisoner Custody Individuals arrested for federal offenses are brought before a U.S. magistrate or U.S. district court judge for their initial court appearances. The court determines whether prisoners are to be released on bond or remanded to the custody of the Marshals to await trial. Generally, slightly less than 65 percent of those arrested by federal agencies are detained at some point in the judicial process. The Marshals received approximately 160,000 individuals in fiscal 2020, or about 640 people a day, and escorted more than 550,000 prisoners, or 2,213 prisoners per day, to court appearances or for other matters in the 94 federal judicial districts in more than 300 court cities. -

Cruel Confinement

Cruel Confinement Abuse, Discrimination and Death Within Alabama’s Prisons A Special Report from the Southern Poverty Law Center and the Alabama Disabilities Advocacy Program Montgomery, Alabama June 2014 Cruel Confinement Abuse, Discrimination and Death Within Alabama’s Prisons MEDIA AND GENERAL INQUIRIES Ashley Levett Southern Poverty Law Center 400 Washington Ave., Montgomery, Ala. (334) 956-8200 © Southern Poverty Law Center. All rights reserved. cruel confinement: abuse, discrimination and death within alabama’s prisons About the Report This report is the result of an investigation by the Southern Poverty Law Center (SPLC) and the Alabama Disabilities Advocacy Program (ADAP). It is based on inspections of Alabama’s 15 prisons; interviews with more than 100 prisoners; a review of thousands of pages of medical records as well as depositions and media accounts; and the policies, contracts and reports of the Alabama Department of Corrections (ADOC) and two of its major contractors. The principal writer was Maria Morris, managing attorney of the SPLC’s Montgomery Legal Office. Contributing writers were J. Patrick Hackney and William Van Der Pol Jr., both staff attorneys for ADAP. The report was edited by Jamie Kizzire and designed by Sunny Paulk, both of the SPLC. For further information, see the SPLC’s letter to the ADOC at http://sp.lc/LetterToCommissioner. About the Southern Poverty Law Center The Southern Poverty Law Center is a Montgomery, Alabama-based nonprofit organization dedicated to fighting hate and bigotry and to seeking justice for the most vulnerable members of our society. Using litigation, education and other forms of advocacy, the SPLC works toward the day when the ideals of equal justice and equal opportunity will be a reality.