Toward a Confessional Theology Within the Churches of Christ

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Enter Your Title Here in All Capital Letters

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by K-State Research Exchange THE BATTLE CRY OF PEACE: THE LEADERSHIP OF THE DISCIPLES OF CHRIST MOVEMENT DURING THE AMERICAN CIVIL WAR, 1861-1865 by DARIN A.TUCK B. A., Washburn University, 2007 A THESIS submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree MASTER OF ARTS Department of History College of Arts and Sciences KANSAS STATE UNIVERSITY Manhattan, Kansas 2010 Approved by: Major Professor Robert D. Linder Copyright DARIN A. TUCK 2010 Abstract As the United States descended into war in 1861, the religious leaders of the nation were among the foremost advocates and recruiters for both the Confederate and Union forces. They exercised enormous influence over the laity, and used their sermons and periodicals to justify, promote, and condone the brutal fratricide. Although many historians have focused on the promoters of war, they have almost completely ignored the Disciples of Christ, a loosely organized religious movement based on anti-sectarianism and primitive Christianity, who used their pulpits and periodicals as a platform for peace. This study attempts to merge the remarkable story of the Disciples peace message into a narrative of the Civil War. Their plea for nonviolence was not an isolated event, but a component of a committed, biblically-based response to the outbreak of war from many of the most prominent leaders of the movement. Immersed in the patriotic calls for war, their stance was extremely unpopular and even viewed as traitorous in their communities and congregations. This study adds to the current Disciples historiography, which states that the issue of slavery and the Civil War divided the movement North and South, by arguing that the peace message professed by its major leaders divided the movement also within the sections. -

The Origins of the Restoration Movement: an Intellectual History, Richard Tristano

Leaven Volume 2 Issue 3 The Restoration Ideal Article 16 1-1-1993 The Origins of the Restoration Movement: An Intellectual History, Richard Tristano Jack R. Reese [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.pepperdine.edu/leaven Part of the Biblical Studies Commons, Christianity Commons, and the Religious Thought, Theology and Philosophy of Religion Commons Recommended Citation Reese, Jack R. (1992) "The Origins of the Restoration Movement: An Intellectual History, Richard Tristano," Leaven: Vol. 2 : Iss. 3 , Article 16. Available at: https://digitalcommons.pepperdine.edu/leaven/vol2/iss3/16 This Book Review is brought to you for free and open access by the Religion at Pepperdine Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Leaven by an authorized editor of Pepperdine Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected], [email protected]. 46 Leaven, Summer1993Reese: The Origins of the Restoration Movement: An Intellectual History, Book ~ e= Reviews •.•.•0 ~Z > ~~. ~(1§3~ Z >'~ ~>C1~ () ~ Jack Reese, Editor ~ ~ ~~;;C= ~tz ~ ~=~~~r-.~ ~ ACHTEMEIER ~CRADDOCK ~ ~~~~=~~ Tr~~Z ~~ ..,-.; C1 LIPSCOMB BOOKSBOOKSBOOKSBOOKSBOOKSBOOKSBOOKSBOOKSBOOKSBOOKS The Second Incarnation: A Theology for the Church," "The Worship ofthe Church," and so on. 21st Century Church What Shelly and Harris promise instead is an ar- Rubel Shelly, Randall J. Harris ticulation of the church as the continuation of the Howard Publishing Company, 1992 ministry ofJesus - a second incarnation. The book asks the question''What if Jesus were a church?" It Shelly and Harris have done their readers a is their hope that this question will provide the great service by articulating in a thoughtful and theological energy for our tradition to move pur- readable way their thinking on the nature of the .posefully into the next century. -

Pentecostal and Charismatic Movements Don Fanning Liberty University, [email protected]

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by Liberty University Digital Commons Liberty University DigitalCommons@Liberty University Trends and Issues in Missions Center for Global Ministries 2009 Pentecostal and Charismatic Movements Don Fanning Liberty University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.liberty.edu/cgm_missions Recommended Citation Fanning, Don, "Pentecostal and Charismatic Movements" (2009). Trends and Issues in Missions. Paper 7. http://digitalcommons.liberty.edu/cgm_missions/7 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Center for Global Ministries at DigitalCommons@Liberty University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Trends and Issues in Missions by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Liberty University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Pentecostal/Charismatic Movements Page 1 Pentecostal Movement The first two hundred years (100-300 AD) The emphasis on the spiritual gifts was evident in the false movements of Gnosticism and in Montanism. The result of this false emphasis caused the Church to react critically against any who would seek to use the gifts. These groups emphasized the gift of prophecy, however, there is no documentation of any speaking in tongues. Montanus said that “after me there would be no more prophecy, but rather the end of the world” (Philip Schaff, History of the Christian Church, Vol II, p. 418). Since his prophecy was not fulfilled, it is obvious that he was a false prophet (Deut . 18:20-22). Because of his stress on new revelations delivered through the medium of unknown utterances or tongues, he said that he was the Comforter, the title of the Holy Spirit (Eusebius, V, XIV). -

History of the Church: Lesson 5 the Restoration Movement

HISTORY OF THE CHURCH: LESSON 5 THE RESTORATION MOVEMENT INTRODUCTION: The reformers sought to REFORM the apostate church, but those active in the Restoration movement were desirous of RESTORING the true church of the first century (cf. Jer.6:16). I. RESTORATION LEADERS: A. James O'Kelly (1757-1826) 1. Methodist preacher who labored in Virginia and North Carolina. 2. Favored congregational government, and the New Testament as the only rule of faith and practice. a) Wanted Methodist preachers to have the right to appeal to the conference if they didn't like their appointment. 3. James O'Kelly, Rice Haggard and three other men withdrew from the conference in 1792. They formed the "Republican Methodist Church" in 1793. 4. In 1794, at a meeting conducted at the Lebanon Church in Surrey County, Virginia, they adopted the name, "Christian" and devised a plan of church government. 5. Agreed to recognize the scriptures as sufficient rule of faith and practice. The formulated the "Five Cardinal Principles of the Christian Church." a) Christ as head of the church. b) The name "Christian" to the exclusion of all others. c) Bible as the only creed - - rule of faith and practice. d) Character, piety, the only test of church fellowship and membership. e) The right of private judgment and liberty of conscience. B. Elias Smith (1769-1846) and Abner Jones (1772-1841) 1. Both Baptists. 2. Agreed with O'Kelly on his major points 3. In 1808, Smith and Jones established churches in New England. 4. Organized an independent "Christian Church" at Lyndon, Vermont in 1801. -

Download PDF 1.11 MB

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2005 Aliens in the World: Sectarians, Secularism and the Second Great Awakening Matt McCook Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF ARTS AND SCIENCES ALIENS IN THE WORLD: SECTARIANS, SECULARISM AND THE SECOND GREAT AWAKENING By MATT MCCOOK A Dissertation submitted to the Department of History in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Degree Awarded: Fall Semester, 2005 The members of the Committee approve the dissertation of Matt McCook defended on August 18, 2005. ______________________________ Neil Jumonville Professor Directing Dissertation ______________________________ Thomas Joiner Outside Committee Member ______________________________ Elna Green Committee Member ______________________________ Albrecht Koschnik Committee Member ______________________________ Amanda Porterfield Committee Member The Office of Graduate Studies has verified and approved the above named committee members. ii The following is dedicated to three individuals whose lives have been and will be affected by this project and its completion as much as mine. One has supported me in every possible way throughout my educational pursuits, sharing the highs, the lows, the sacrifices, the frustration, but always being patient with me and believing in me more than I believed in myself. The second has inspired me to go back to the office to work many late nights while at the same time being the most welcome distraction constantly reminding me of what I value most. And the anticipated arrival of the third has inspired me to finish so that this precious child would not have to share his or her father with a dissertation. -

Like Fire in Dry Stubble - the Ts One Movement 1804-1832 (Part 2) R

Restoration Quarterly Volume 8 | Number 1 Article 1 1-1-1965 Like Fire in Dry Stubble - The tS one Movement 1804-1832 (Part 2) R. L. Roberts J W. Roberts Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.acu.edu/restorationquarterly Part of the Biblical Studies Commons, Christian Denominations and Sects Commons, Christianity Commons, Comparative Methodologies and Theories Commons, History of Christianity Commons, Liturgy and Worship Commons, Missions and World Christianity Commons, Practical Theology Commons, and the Religious Thought, Theology and Philosophy of Religion Commons Recommended Citation Roberts, R. L. and Roberts, J W. (1965) "Like Fire in Dry Stubble - The tS one Movement 1804-1832 (Part 2)," Restoration Quarterly: Vol. 8 : No. 1 , Article 1. Available at: https://digitalcommons.acu.edu/restorationquarterly/vol8/iss1/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ ACU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Restoration Quarterly by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ ACU. RESTORATION QUARTERLY CONTENTS The Biblical Doct r ine of the People of God-Richard Bat ey.......... 2 Introduction to Sept uagintal Studies ( continued ) -George Howard . .................................. ................. .............. ..... 10 Like Fire in Dry Stubb le- Th e Stone Movement 1804-1832 (Part 11)-R. L. and J. W. Roberts . .................... .................. 26 The Typology of Baptism in the Early Church -Everett F erguso n ... .............................. .......................... 41 Matthew 10:23 and Eschato logy (11)-Ro yce Clark ......... ........... .. 53 A Note on the "Double Portion" of Deuteronomy 21 :17 and II Kings 2:9-Pa ul Watson ............................. .......... 70 Book Reviews . .................... .. ················· .... 76 STUDIES IN CHRISTIAN SCHOLARSHIP VOL. 8. NO. 1 FIRST QUARTER, 1965 Like Fire in Dry Stubble.... -

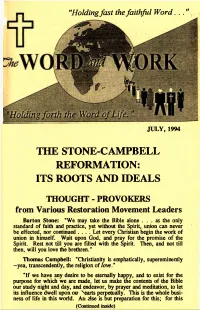

The Stone-Campbell Reformation: Its Roots and Ideals

"Holding fast the faithful W ord ...", JU L Y , 1994 THE STONE-CAMPBELL REFORMATION: ITS ROOTS AND IDEALS THOUGHT - PROVOKERS from Various Restoration Movement Leaders Barton Stone: "We may take the Bible alone . as the only standard of faith and practice, yet without the Spirit, union can never be effected, nor continued .... Let every Christian begin the work of union in himself. Wait upon God, and pray for the promise o f the Spirit. Rest not till you are filled with the Spirit. Then, and not till then, will you love the brethren." Thomas Campbell: "Christianity is emphatically, supereminently -yea, transcendency, the religion of lo v e ." "If we have any desire to be eternally happy, and to exist for the purpose for which we are made, let us make the contents of the Bible our study night and day, and endeavor, by prayer and meditation, to let its influence dwell upon our hearts perpetually. This is the whole busi ness of life in this world. All else is but preparation for this; for this (Continued inside) alone can lead us back to God, the eternal Fountain of all being and blessedness. He is both the Author and the Object of the Bible. It comes from Him, and is graciously designed to lead us to Him . ." Alexander Campbell, writes Richard Hughes, "often insisted that mere intellectual assent to gospel facts is not saving faith. The faith that saves, he urged, ’is not belief or any doctrine or truth, ab stractly, but belief in Christ; trust or confidence in Him as a per- son. -

Recent Patterns of Growth and Decline Among Heirs of the Restoration Movement

Restoration Quarterly Volume 37 Number 1 Article 3 1-1-1995 Recent Patterns of Growth and Decline among Heirs of the Restoration movement Flavil Yeakley Jr. Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.acu.edu/restorationquarterly Part of the Biblical Studies Commons, Christian Denominations and Sects Commons, Christianity Commons, Comparative Methodologies and Theories Commons, History of Christianity Commons, Liturgy and Worship Commons, Missions and World Christianity Commons, Practical Theology Commons, and the Religious Thought, Theology and Philosophy of Religion Commons Recommended Citation Yeakley, Flavil Jr. (1995) "Recent Patterns of Growth and Decline among Heirs of the Restoration movement," Restoration Quarterly: Vol. 37 : No. 1 , Article 3. Available at: https://digitalcommons.acu.edu/restorationquarterly/vol37/iss1/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Digital Commons @ ACU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Restoration Quarterly by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ ACU. ResLoRaLfon uaRLeRLcY VOLUME 37/NUMBE R 1 FIRST QUARTER 1995 ISSN 0486-5642 l Hermeneutics in the Churches of Christ THOMAS H. OLBRICHT 28 Alexander Campbell as a Publisher GARY HOLLOWAY 36 Sociological Methods in the Study of the New Testament A Review and Assessment THOMAS SCOTT CAULLEY 45 Recent Patterns of Growth and Decline among Heirs of the Restoration Movement FLAVIL YEAKLEY, JR. 51 Book Reviews 63 Book Notes RECENT PATTERNS OF GROWTH AND DECLINE AMONG HEIRS OF THE RESTORATION MOVEMENT FLA VIL YEAKLEY, JR. Harding University Three heirs of the Restoration Movement are listed in most almanacs and yearbooks. One such reference work is Churches and Church Membership in the United States 1990. -

Discipliana Vol-13-Nos-1-7-April-1953-December-1953

Disciples of Christ Historical Society Digital Commons @ Disciples History Discipliana - Archival Issues 1953 Discipliana Vol-13-Nos-1-7-April-1953-December-1953 Claude E. Spencer Disciples of Christ Historical Society, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.discipleshistory.org/discipliana Part of the Christian Denominations and Sects Commons, History of Religion Commons, Religious Thought, Theology and Philosophy of Religion Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Spencer, Claude E., "Discipliana Vol-13-Nos-1-7-April-1953-December-1953" (1953). Discipliana - Archival Issues. 11. https://digitalcommons.discipleshistory.org/discipliana/11 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ Disciples History. It has been accepted for inclusion in Discipliana - Archival Issues by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Disciples History. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Published quarterly by the Disciples of Christ Historical Society, Nashville, Tennessee VOL. 13 APRIL, 1953 NO. STATE CONVENTIONS ENDORSE DCHS Society Maintains Exhibits -------------FAMILY FOUNDATION at Spring Meetings TAKES Resolutions endorsing the program of the CONTRIBUTING MEMBERSHIP Disciples of Christ Histori~al ~ociety a~ter The Disciples of Christ Historical Society one year of full-time operation 10 NashvIlle reports the receipts of a ~500 contribu~ing have been adopted by nine (9~ state co~v~n- membership from the Irw1O-Sweeney-Ml11er tions of Disciples of Chnst (Chnstran Foundation of Columbus, Indiana. The Churches). The J:.esolutions called attention Foundation represents the interests of Mr. to the work of the Society in collecting and and Mrs. Irwin Miller, Mrs. -

The Work and Influence of Barton W. Stone

The Work And Influence Of Barton W. Stone • Born In 1772 – Port Tobacco, Barton Maryland Warren • Father Died When He Was Young Stone • Moved South During His Youth • During Revolutionary War, He Lived In Alamance County, North Carolina When Cornwallis Met General Green At The Battle Of Guilford Courthouse, Though 30 Miles Away Could Hear The Sounds Of Artillery Causing Great Fear • At The Age Of 15 or 16 He Decided He Wanted To Be Educated To Become An Attorney • Feb 1, 1790, Age 18, Attends Doctor David Caldwell’s Guilford Academy • Born In Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, March David 22nd, 1725 • Graduated from Princeton in 1761 Caldwell • Licensed To Preach By The Presbytery Of New 1725-1821 Brunswick, June 8th, 1763 • 1765 While Doing Mission Work In North Carolina, He Started A Log Cabin School In Guilford County • 1766 Married Rachel Craighead, Daughter of Presbyterian Minister, Alexander Craighead • 1768, He Was Installed As Minister Of The Two Presbyterian Churches In Buffalo and Alamance Settlements • 1769 Began His Academy At Greensboro, N.C. • During Revolutionary War, Gen. Cornwallis offered a £200 Reward For His Capture For Speaking Out Against The Crown – Home Destroyed By Fire, Including Library By British • 1776, Member Of The Convention That Formed The Constitution Of The State Of North Carolina • 1789 When University of N.C. Was Chartered Caldwell Was Offered The Presidency • His School Sent Out Over 50 Preachers, 5 Governors, Congressmen, Physicians, David Lawyers & Judges • 1790 – 65 Years Of Age When B.W. Stone Caldwell Became Student 1725-1821 • Continued To Preach In His Two Churches Till The Year 1820 • Preached Often At Hawfields Church Where B.W. -

Views and Experiences from a Colonial Past to Their Unfamiliar New Surroundings

MIAMI UNIVERSITY The Graduate School Certificate for Approving the Dissertation We hereby approve the Dissertation of Matthew David Smith Candidate for the Degree: Doctor of Philosophy ____________________________________________ Director Dr. Carla Gardina Pestana _____________________________________________ Reader Dr. Andrew R.L. Cayton _____________________________________________ Reader Dr. Mary Kupiec Cayton ____________________________________________ Reader Dr. Katharine Gillespie ____________________________________________ Dr. Peter Williams Graduate School Representative ABSTRACT "IN THE LAND OF CANAAN:" RELIGIOUS REVIVAL AND REPUBLICAN POLITICS IN EARLY KENTUCKY by Matthew Smith Against the tumult of the American Revolution, the first white settlers in the Ohio Valley imported their religious worldviews and experiences from a colonial past to their unfamiliar new surroundings. Within a generation, they witnessed the Great Revival (circa 1797-1805), a dramatic mass revelation of religion, converting thousands of worshipers to spiritual rebirth while transforming the region's cultural identity. This study focuses on the lives and careers of three prominent Kentucky settlers: Christian revivalists James McGready and Barton Warren Stone, and pioneering newspaper editor John Bradford. All three men occupy points on a religious spectrum, ranging from the secular public faith of civil religion, to the apocalyptic sectarianism of the Great Revival, yet they also overlap in unexpected ways. This study explores how the evangelicalism -

Causes of Restoration

Causes Of Restoration M.M. Davis in How The Disciples Began And Grew related seven significant things at work in religion that brought about the Restoration Movement The Renaissance • Movement of transition in Europe from medieval to modern world, especially classical arts and letters. • Earliest Traces To 14th Century Italy • Within 100 years Italy brought in Greek literature • Reached its zenith by 1st of 16th Century through men like Michelangelo, Leonardo da Vinci and Raphael. • Soon spread to Germany and England • The students of science, philosophy and religion started looking for the sources of things. • Two Fundamental Principles – The Right of Private Judgment – The Bible when studied would produce unity among Christians as it did in the 1st Century The Divided Church • In light of Jesus’ teaching in John 17:11-23, unity was not only possible, but commanded. • Other passages promoting unity: John 10:16; 1 Corinthians 1:10; 3:3; 12:12-27 • Churches in their day were far from will or disposition to do promote unity • Such divisions as existed weakened the forces of God – Instead of one force for God, there were many small detachments jealously watching each other rather than the common foe A Warring Church • Churches were devouring one another • Protestant Churches were physical enemies of the Rome Church • Public displays of rhetorical hatred was spouted forth • Physical engagements and wars often resulted • A house divided can not stand! Matthew 12:25,26 Beclouded Theology • The blind were leading the blind, and both falling