Practicing Law As a Christian: Restoration Movement Perspectives Thomas G

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Toward a Confessional Theology Within the Churches of Christ

Please HONOR the copyright of these documents by not retransmitting or making any additional copies in any form (Except for private personal use). We appreciate your respectful cooperation. ___________________________ Theological Research Exchange Network (TREN) P.O. Box 30183 Portland, Oregon 97294 USA Website: www.tren.com E-mail: [email protected] Phone# 1-800-334-8736 ___________________________ ATTENTION CATALOGING LIBRARIANS TREN ID# Online Computer Library Center (OCLC) MARC Record # Digital Object Identification DOI # Ministry Focus Paper Approval Sheet This ministry focus paper entitled WE CAN BEAR IT NO LONGER: TOWARD A CONFESSIONAL THEOLOGY WITHIN THE CHURCHES OF CHRIST Written by PAUL A. SMITH and submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Ministry has been accepted by the Faculty of Fuller Theological Seminary upon the recommendation of the undersigned readers: _____________________________________ John W. Drane _____________________________________ Kurt Fredrickson Date Received: March 15, 2015 WE CAN BEAR IT NO LONGER: TOWARD A CONFESSIONAL THEOLOGY WITHIN THE CHURCHES OF CHRIST A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE SCHOOL OF THEOLOGY FULLER THEOLOGICAL SEMINARY IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE DOCTOR OF MINISTRY BY PAUL A. SMITH MARCH 2015 ABSTRACT We Can Bear It No Longer: Toward a Confessional Theology within the Churches of Christ Paul A. Smith Doctor of Ministry School of Theology, Fuller Theological Seminary 2014 The purpose of this study was to demonstrate the need for members of the Churches of Christ to restore confession in both private and communal worship practices. The major premise is that the men who inspired the movement that gave birth to the modern Churches of Christ either ignored or misunderstood the secular philosophies that influenced their work. -

The Origins of the Restoration Movement: an Intellectual History, Richard Tristano

Leaven Volume 2 Issue 3 The Restoration Ideal Article 16 1-1-1993 The Origins of the Restoration Movement: An Intellectual History, Richard Tristano Jack R. Reese [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.pepperdine.edu/leaven Part of the Biblical Studies Commons, Christianity Commons, and the Religious Thought, Theology and Philosophy of Religion Commons Recommended Citation Reese, Jack R. (1992) "The Origins of the Restoration Movement: An Intellectual History, Richard Tristano," Leaven: Vol. 2 : Iss. 3 , Article 16. Available at: https://digitalcommons.pepperdine.edu/leaven/vol2/iss3/16 This Book Review is brought to you for free and open access by the Religion at Pepperdine Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Leaven by an authorized editor of Pepperdine Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected], [email protected]. 46 Leaven, Summer1993Reese: The Origins of the Restoration Movement: An Intellectual History, Book ~ e= Reviews •.•.•0 ~Z > ~~. ~(1§3~ Z >'~ ~>C1~ () ~ Jack Reese, Editor ~ ~ ~~;;C= ~tz ~ ~=~~~r-.~ ~ ACHTEMEIER ~CRADDOCK ~ ~~~~=~~ Tr~~Z ~~ ..,-.; C1 LIPSCOMB BOOKSBOOKSBOOKSBOOKSBOOKSBOOKSBOOKSBOOKSBOOKSBOOKS The Second Incarnation: A Theology for the Church," "The Worship ofthe Church," and so on. 21st Century Church What Shelly and Harris promise instead is an ar- Rubel Shelly, Randall J. Harris ticulation of the church as the continuation of the Howard Publishing Company, 1992 ministry ofJesus - a second incarnation. The book asks the question''What if Jesus were a church?" It Shelly and Harris have done their readers a is their hope that this question will provide the great service by articulating in a thoughtful and theological energy for our tradition to move pur- readable way their thinking on the nature of the .posefully into the next century. -

CIVIL GOVERNMENT. Its Origin, Mission, and Destiny

CIVIL GOVERNMENT. Its Origin, Mission, and Destiny, - AND THE - Christian's Relation To It. BY D. LIPSCOMB. NASHVILLE, TENN.: McQUIDDY PRINTING CO., 1913. Contents: Preface Chapter 2 Chapter 3 Chapter 4 iii Preface The writer of the following pages was early in life impressed with the idea that God as the Creator, and preserver of the world, was its only rightful law-maker and ruler. And that all the evil that afflicted humanity and the world, had arisen from a failure on the part of man to whom the rule of the earth had been committed by God, to maintain in its purity and sovereignty the authority and dominion of God as the only rule of this world. From the Bible he learned man had sinned against God, that an element of discord and confusion had hence entered into the world, and the world was out of harmonious relations with God and the universe. This being true, it early occurred to his mind, that the one sure and sovereign remedy for these evils, was the absolute submission to God on the part of man, and a restoration of his authority and rule in all the domains of the world. In the study of the Bible, he saw the one purpose of God, as set forth in that book, was to bring man back under his own rule and government so to re-establish his authority and rule on earth, that God's will "shall be done on earth as it is in Heaven." To this end, man's duty is to learn the will of God, and trustingly do that will, leaving results and events with God. -

Pentecostal and Charismatic Movements Don Fanning Liberty University, [email protected]

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by Liberty University Digital Commons Liberty University DigitalCommons@Liberty University Trends and Issues in Missions Center for Global Ministries 2009 Pentecostal and Charismatic Movements Don Fanning Liberty University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.liberty.edu/cgm_missions Recommended Citation Fanning, Don, "Pentecostal and Charismatic Movements" (2009). Trends and Issues in Missions. Paper 7. http://digitalcommons.liberty.edu/cgm_missions/7 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Center for Global Ministries at DigitalCommons@Liberty University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Trends and Issues in Missions by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Liberty University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Pentecostal/Charismatic Movements Page 1 Pentecostal Movement The first two hundred years (100-300 AD) The emphasis on the spiritual gifts was evident in the false movements of Gnosticism and in Montanism. The result of this false emphasis caused the Church to react critically against any who would seek to use the gifts. These groups emphasized the gift of prophecy, however, there is no documentation of any speaking in tongues. Montanus said that “after me there would be no more prophecy, but rather the end of the world” (Philip Schaff, History of the Christian Church, Vol II, p. 418). Since his prophecy was not fulfilled, it is obvious that he was a false prophet (Deut . 18:20-22). Because of his stress on new revelations delivered through the medium of unknown utterances or tongues, he said that he was the Comforter, the title of the Holy Spirit (Eusebius, V, XIV). -

History of the Church: Lesson 5 the Restoration Movement

HISTORY OF THE CHURCH: LESSON 5 THE RESTORATION MOVEMENT INTRODUCTION: The reformers sought to REFORM the apostate church, but those active in the Restoration movement were desirous of RESTORING the true church of the first century (cf. Jer.6:16). I. RESTORATION LEADERS: A. James O'Kelly (1757-1826) 1. Methodist preacher who labored in Virginia and North Carolina. 2. Favored congregational government, and the New Testament as the only rule of faith and practice. a) Wanted Methodist preachers to have the right to appeal to the conference if they didn't like their appointment. 3. James O'Kelly, Rice Haggard and three other men withdrew from the conference in 1792. They formed the "Republican Methodist Church" in 1793. 4. In 1794, at a meeting conducted at the Lebanon Church in Surrey County, Virginia, they adopted the name, "Christian" and devised a plan of church government. 5. Agreed to recognize the scriptures as sufficient rule of faith and practice. The formulated the "Five Cardinal Principles of the Christian Church." a) Christ as head of the church. b) The name "Christian" to the exclusion of all others. c) Bible as the only creed - - rule of faith and practice. d) Character, piety, the only test of church fellowship and membership. e) The right of private judgment and liberty of conscience. B. Elias Smith (1769-1846) and Abner Jones (1772-1841) 1. Both Baptists. 2. Agreed with O'Kelly on his major points 3. In 1808, Smith and Jones established churches in New England. 4. Organized an independent "Christian Church" at Lyndon, Vermont in 1801. -

~Tate of {[Enne~~Ee

~tate of {[enne~~ee HOUSE RESOLUTION NO. 55 By Madam Speaker Harwell, Representatives DeBerry, Dunlap, Mark White, Butt A RESOLUTION recognizing the Gospel Advocate on the celebration of its 160th anniversary. WHEREAS, the members of this legislative body are honored to recognize those storied organizations and institutions that are celebrating momentous, notable occasions in their histories; and WHEREAS, the Gospel Advocate, a religious magazine published monthly in Nashville for members of the Churches of Christ, is one such institution, which is, this year, celebrating the 160th anniversary of its founding; and WHEREAS, the Gospel Advocate has been conservative and Bible-based throughout its history, and it has remained committed to "the interests of the church of Jesus Christ, and especially, to the maintenance of the doctrine of salvation through the 'Gospel of the Grace of God"'; and WHEREAS, the Gospel Advocate also publishes Sunday school materials and operates Christian bookstores in Nashville and Mesquite, Texas; and WHEREAS, founded in Nashville by Restoration Movement preacher Tolbert Fanning in July of 1855, the Gospel Advocate has served as a beacon of Christian faith and education for the past 160 years; and WHEREAS, at the founding of the publication, Mr. Fanning was assisted in his efforts by his student, William Lipscomb, who served as co-editor until they were forced to suspend publication due to the outbreak of war in 1861; and WHEREAS, publication resumed following the end of the Civil War, and since 1866, the Gospel Advocate has been published without interruption. Upon its resurrection in 1866, the publication was again led by editors Tolbert Fanning and William Lipscomb, who were joined in this endeavor by Mr. -

Our Cloud of Witnesses

Leaven Volume 1 Issue 3 The Worldly Church Article 21 1-1-1990 Our Cloud of Witnesses Doug Foster [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.pepperdine.edu/leaven Part of the Biblical Studies Commons, Christianity Commons, and the Religious Thought, Theology and Philosophy of Religion Commons Recommended Citation Foster, Doug (1990) "Our Cloud of Witnesses," Leaven: Vol. 1 : Iss. 3 , Article 21. Available at: https://digitalcommons.pepperdine.edu/leaven/vol1/iss3/21 This Biography is brought to you for free and open access by the Religion at Pepperdine Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Leaven by an authorized editor of Pepperdine Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected], [email protected]. 50 LEAVEN Summer 1990 Foster: Our Cloud of Witnesses Historical Sketches OF WITNESSES David Lipscomb: The Gentle Teacher different from his own. He insisted that since no one had learned all truth on any given subject, there was a by Doug Foster constant need to examine all sides of the questions. "[Llet us not despise or reject him who is seeking and For almost fifty years David Lipscomb shaped the striving to learn the will of God, because he has not beliefs of thousands in the Restoration Movement learned so much ofthe truth as we think we have." It through the pages of the Gospel Advocate. From the was imperative, he believed, that constant investiga- beginning of his editorial career in 1866, however, tion and discussion of differences go on to promote Lipscomb faced opposition to his views on everything unity. -

Download PDF 1.11 MB

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2005 Aliens in the World: Sectarians, Secularism and the Second Great Awakening Matt McCook Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF ARTS AND SCIENCES ALIENS IN THE WORLD: SECTARIANS, SECULARISM AND THE SECOND GREAT AWAKENING By MATT MCCOOK A Dissertation submitted to the Department of History in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Degree Awarded: Fall Semester, 2005 The members of the Committee approve the dissertation of Matt McCook defended on August 18, 2005. ______________________________ Neil Jumonville Professor Directing Dissertation ______________________________ Thomas Joiner Outside Committee Member ______________________________ Elna Green Committee Member ______________________________ Albrecht Koschnik Committee Member ______________________________ Amanda Porterfield Committee Member The Office of Graduate Studies has verified and approved the above named committee members. ii The following is dedicated to three individuals whose lives have been and will be affected by this project and its completion as much as mine. One has supported me in every possible way throughout my educational pursuits, sharing the highs, the lows, the sacrifices, the frustration, but always being patient with me and believing in me more than I believed in myself. The second has inspired me to go back to the office to work many late nights while at the same time being the most welcome distraction constantly reminding me of what I value most. And the anticipated arrival of the third has inspired me to finish so that this precious child would not have to share his or her father with a dissertation. -

Like Fire in Dry Stubble - the Ts One Movement 1804-1832 (Part 2) R

Restoration Quarterly Volume 8 | Number 1 Article 1 1-1-1965 Like Fire in Dry Stubble - The tS one Movement 1804-1832 (Part 2) R. L. Roberts J W. Roberts Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.acu.edu/restorationquarterly Part of the Biblical Studies Commons, Christian Denominations and Sects Commons, Christianity Commons, Comparative Methodologies and Theories Commons, History of Christianity Commons, Liturgy and Worship Commons, Missions and World Christianity Commons, Practical Theology Commons, and the Religious Thought, Theology and Philosophy of Religion Commons Recommended Citation Roberts, R. L. and Roberts, J W. (1965) "Like Fire in Dry Stubble - The tS one Movement 1804-1832 (Part 2)," Restoration Quarterly: Vol. 8 : No. 1 , Article 1. Available at: https://digitalcommons.acu.edu/restorationquarterly/vol8/iss1/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ ACU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Restoration Quarterly by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ ACU. RESTORATION QUARTERLY CONTENTS The Biblical Doct r ine of the People of God-Richard Bat ey.......... 2 Introduction to Sept uagintal Studies ( continued ) -George Howard . .................................. ................. .............. ..... 10 Like Fire in Dry Stubb le- Th e Stone Movement 1804-1832 (Part 11)-R. L. and J. W. Roberts . .................... .................. 26 The Typology of Baptism in the Early Church -Everett F erguso n ... .............................. .......................... 41 Matthew 10:23 and Eschato logy (11)-Ro yce Clark ......... ........... .. 53 A Note on the "Double Portion" of Deuteronomy 21 :17 and II Kings 2:9-Pa ul Watson ............................. .......... 70 Book Reviews . .................... .. ················· .... 76 STUDIES IN CHRISTIAN SCHOLARSHIP VOL. 8. NO. 1 FIRST QUARTER, 1965 Like Fire in Dry Stubble.... -

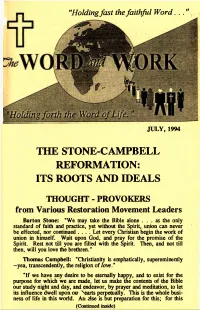

The Stone-Campbell Reformation: Its Roots and Ideals

"Holding fast the faithful W ord ...", JU L Y , 1994 THE STONE-CAMPBELL REFORMATION: ITS ROOTS AND IDEALS THOUGHT - PROVOKERS from Various Restoration Movement Leaders Barton Stone: "We may take the Bible alone . as the only standard of faith and practice, yet without the Spirit, union can never be effected, nor continued .... Let every Christian begin the work of union in himself. Wait upon God, and pray for the promise o f the Spirit. Rest not till you are filled with the Spirit. Then, and not till then, will you love the brethren." Thomas Campbell: "Christianity is emphatically, supereminently -yea, transcendency, the religion of lo v e ." "If we have any desire to be eternally happy, and to exist for the purpose for which we are made, let us make the contents of the Bible our study night and day, and endeavor, by prayer and meditation, to let its influence dwell upon our hearts perpetually. This is the whole busi ness of life in this world. All else is but preparation for this; for this (Continued inside) alone can lead us back to God, the eternal Fountain of all being and blessedness. He is both the Author and the Object of the Bible. It comes from Him, and is graciously designed to lead us to Him . ." Alexander Campbell, writes Richard Hughes, "often insisted that mere intellectual assent to gospel facts is not saving faith. The faith that saves, he urged, ’is not belief or any doctrine or truth, ab stractly, but belief in Christ; trust or confidence in Him as a per- son. -

Recent Patterns of Growth and Decline Among Heirs of the Restoration Movement

Restoration Quarterly Volume 37 Number 1 Article 3 1-1-1995 Recent Patterns of Growth and Decline among Heirs of the Restoration movement Flavil Yeakley Jr. Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.acu.edu/restorationquarterly Part of the Biblical Studies Commons, Christian Denominations and Sects Commons, Christianity Commons, Comparative Methodologies and Theories Commons, History of Christianity Commons, Liturgy and Worship Commons, Missions and World Christianity Commons, Practical Theology Commons, and the Religious Thought, Theology and Philosophy of Religion Commons Recommended Citation Yeakley, Flavil Jr. (1995) "Recent Patterns of Growth and Decline among Heirs of the Restoration movement," Restoration Quarterly: Vol. 37 : No. 1 , Article 3. Available at: https://digitalcommons.acu.edu/restorationquarterly/vol37/iss1/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Digital Commons @ ACU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Restoration Quarterly by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ ACU. ResLoRaLfon uaRLeRLcY VOLUME 37/NUMBE R 1 FIRST QUARTER 1995 ISSN 0486-5642 l Hermeneutics in the Churches of Christ THOMAS H. OLBRICHT 28 Alexander Campbell as a Publisher GARY HOLLOWAY 36 Sociological Methods in the Study of the New Testament A Review and Assessment THOMAS SCOTT CAULLEY 45 Recent Patterns of Growth and Decline among Heirs of the Restoration Movement FLAVIL YEAKLEY, JR. 51 Book Reviews 63 Book Notes RECENT PATTERNS OF GROWTH AND DECLINE AMONG HEIRS OF THE RESTORATION MOVEMENT FLA VIL YEAKLEY, JR. Harding University Three heirs of the Restoration Movement are listed in most almanacs and yearbooks. One such reference work is Churches and Church Membership in the United States 1990. -

The Work and Influence of Barton W. Stone

The Work And Influence Of Barton W. Stone • Born In 1772 – Port Tobacco, Barton Maryland Warren • Father Died When He Was Young Stone • Moved South During His Youth • During Revolutionary War, He Lived In Alamance County, North Carolina When Cornwallis Met General Green At The Battle Of Guilford Courthouse, Though 30 Miles Away Could Hear The Sounds Of Artillery Causing Great Fear • At The Age Of 15 or 16 He Decided He Wanted To Be Educated To Become An Attorney • Feb 1, 1790, Age 18, Attends Doctor David Caldwell’s Guilford Academy • Born In Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, March David 22nd, 1725 • Graduated from Princeton in 1761 Caldwell • Licensed To Preach By The Presbytery Of New 1725-1821 Brunswick, June 8th, 1763 • 1765 While Doing Mission Work In North Carolina, He Started A Log Cabin School In Guilford County • 1766 Married Rachel Craighead, Daughter of Presbyterian Minister, Alexander Craighead • 1768, He Was Installed As Minister Of The Two Presbyterian Churches In Buffalo and Alamance Settlements • 1769 Began His Academy At Greensboro, N.C. • During Revolutionary War, Gen. Cornwallis offered a £200 Reward For His Capture For Speaking Out Against The Crown – Home Destroyed By Fire, Including Library By British • 1776, Member Of The Convention That Formed The Constitution Of The State Of North Carolina • 1789 When University of N.C. Was Chartered Caldwell Was Offered The Presidency • His School Sent Out Over 50 Preachers, 5 Governors, Congressmen, Physicians, David Lawyers & Judges • 1790 – 65 Years Of Age When B.W. Stone Caldwell Became Student 1725-1821 • Continued To Preach In His Two Churches Till The Year 1820 • Preached Often At Hawfields Church Where B.W.