Marcel Proust's Performative Call to Philosophy of Communication David Deiuliis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sharma 958..960

Copyright #ERS Journals Ltd 2000 Eur Respir J 2000; 15: 958±960 European Respiratory Journal Printed in UK ± all rights reserved ISSN 0903-1936 HISTORICAL NOTE Marcel Proust (1871±1922): reassessment of his asthma and other maladies O.P. Sharma Marcel Proust (1871±1922): reassessment of his asthma and other maladies. O.P. Sharma. Correspondence: O.P. Sharma, USC #ERS Journals Ltd 2000. School of Medicine, LAC+USC Medical ABSTRACT: Marcel Proust endured severe allergies and bronchial asthma from Centre, 1200 N. State St., Room 11-900, early childhood. Those who suffer from the frightening and recurrent pangs of asthma Los Angeles, CA 90033, USA. Fax: 323 2262738 often become dependent on their parents particularly mother; Proust was no exception. In his time asthma was poorly understood by physicians who considered Received: December 21 1999 the illness to be a type of hysteria. Decades later, we now understand that the severe, Accepted after revision January 17 2000 poorly controlled, suffocating episodes of asthma were responsible for the complex persona that Marcel Proust had assumed. Eur Respir J 2000; 15: 958±960. Adrien Proust was a famous clinician and epidemiol- the night. Proust never could master the unpredictability of ogist. He was Chef de Clinique at the Hospital de la Charite asthma exacerbations. He was forced to lead a life of ex- and a consultant at Parvis Notre-Dame and Hotel-Dieu clusion avoiding all contacts with natural and man made France. Despite a busy clinical practice he devoted much agents that provoked asthma. of his time to studying the epidemiology of cholera and Not only did Proust suffer from severe bronchospasms bubonic plague. -

Pynchon Nods: Proust in Gravity's Rainbow Date: 2012 Volume: 1 Issue: 1 URL: DOI: 10.7766/Orbit.V1.1.30

Orbit: Writing Around Pynchon https://www.pynchon.net ISSN: 2044-4095 Author(s): Erik Ketzan Affiliation(s): Institut für Deutsche Sprache, Mannheim, Germany Title: Pynchon Nods: Proust in Gravity's Rainbow Date: 2012 Volume: 1 Issue: 1 URL: https://www.pynchon.net/owap/article/view/30 DOI: 10.7766/orbit.v1.1.30 Abstract: This paper argues that Pynchon may allude to Marcel Proust through the character Marcel in Part 4 of Gravity's Rainbow and, if so, what that could mean. I trace the textual clues that relate to Proust and analyze what Pynchon may be saying about a fellow great experimental writer. Pynchon Nods: Proust in Gravity's Rainbow Erik Ketzan Editorial note: a previous draft of this paper appeared on The Modern Word in 2010. Remember the "Floundering Four" part in Gravity's Rainbow? It's a short story of sorts that takes place in a city of the future called Raketen-Stadt (German for "Rocket City") and features a cast of comic book-style super heroes called the Floundering Four. One of them is named Marcel, and I submit that he is meant as some kind of representation of the great Marcel Proust. Only eight pages long, the Floundering Four section is a parody/riff on a sci-fi comic book story, loosely patterned on The Fantastic Four by Marvel Comics. It appears near the end of Gravity's Rainbow among a set of thirteen chapterettes, each one a fragmentary "text". As Pynchon scholar Steven Weisenburger explains, "A variety of discourses, modes and forms are parodied in the… subsections.. -

1 Matt Phillips, 'French Studies: Literature, 2000 to the Present Day

1 Matt Phillips, ‘French Studies: Literature, 2000 to the Present Day’, Year’s Work in Modern Language Studies, 80 (2020), 209–260 DOI for published version: https://doi.org/10.1163/22224297-08001010 [TT] Literature, 2000 to the Present Day [A] Matt Phillips, Royal Holloway, University of London This survey covers the years 2017 and 2018 [H2]1. General Alexandre Gefen, Réparer le monde: la littérature française face au XXIe siècle, Corti, 2017, 392 pp., argues that contemporary French literature has undergone a therapeutic turn, with both writing and reading now conceived in terms of healing, helping, and doing good. G. defends this thesis with extraordinary thoroughness as he examines the turn’s various guises: as objects of literature’s care here feature the self and its fractures; trauma, both individual and collective; illness, mental and physical; mourning and forgetfulness, personal and historical; and endangered bonds, with humans and beyond, on local and global scales. This amounts to what G. calls a new ‘paradigme clinique’ and, like any paradigm shift, this one appears replete with contradictions, tensions, and opponents, not least owing to the residual influence of preceding paradigms; G.’s analysis is especially impressive when unpicking the ways in which contemporary writers negotiate their sustained attachments to a formal, intransitive conception of literature, and/or more overtly revolutionary political projects. His thesis is supported by an enviable breadth of reference: G. lays out the diverse intellectual, technological, and socioeconomic histories at work in this development, and touches on close to 200 contemporary writers. Given the broad, synthetic nature of the work’s endeavour, individual writers/works are rarely discussed for longer than a page, and though G.’s commentary is always insightful, specialists on particular authors or social/historical trends will surely find much to work with and against here. -

Jonathan Greenberg

Losing Track of Time Jonathan Greenberg Ottessa Moshfegh’s My Year of Rest and Relaxation tells a story of doing nothing; it is an antinovel whose heroine attempts to sleep for a year in order to lose track of time. This desire to lose track of time constitutes a refusal of plot, a satiric and passive- aggressive rejection of the kinds of narrative sequences that novels typically employ but that, Moshfegh implies, offer nothing but accommodation to an unhealthy late capitalist society. Yet the effort to stifle plot is revealed, paradoxically, as an ambi- tion to be achieved through plot, and so in resisting what novels do, My Year of Rest and Relaxation ends up showing us what novels do. Being an antinovel turns out to be just another way of being a novel; in seeking to lose track of time, the novel at- tunes us to our being in time. Whenever I woke up, night or day, I’d shuffle through the bright marble foyer of my building and go up the block and around the corner where there was a bodega that never closed.1 For a long time I used to go to bed early.2 he first of these sentences begins Ottessa Moshfegh’s 2018 novelMy Year of Rest and Relaxation; the second, Proust’s In Search of Lost Time. More ac- T curately, the second sentence begins C. K. Scott Moncrieff’s translation of Proust, whose French reads, “Longtemps, je me suis couché de bonne heure.” D. J. Enright emends the translation to “I would go to bed”; Lydia Davis and Google Translate opt for “I went to bed.” What the translators famously wrestle with is how to render Proust’s ungrammatical combination of the completed action of the passé composé (“went to bed”) with a modifier (“long time”) that implies a re- peated, habitual, or everyday action. -

Y 2 0 ANDRE MALRAUX: the ANTICOLONIAL and ANTIFASCIST YEARS DISSERTATION Presented to the Graduate Council of the University Of

Y20 ANDRE MALRAUX: THE ANTICOLONIAL AND ANTIFASCIST YEARS DISSERTATION Presented to the Graduate Council of the University of North Texas in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY By Richard A. Cruz, B.A., M.A. Denton, Texas May, 1996 Y20 ANDRE MALRAUX: THE ANTICOLONIAL AND ANTIFASCIST YEARS DISSERTATION Presented to the Graduate Council of the University of North Texas in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY By Richard A. Cruz, B.A., M.A. Denton, Texas May, 1996 Cruz, Richard A., Andre Malraux: The Anticolonial and Antifascist Years. Doctor of Philosophy (History), May, 1996, 281 pp., 175 titles. This dissertation provides an explanation of how Andr6 Malraux, a man of great influence on twentieth century European culture, developed his political ideology, first as an anticolonial social reformer in the 1920s, then as an antifascist militant in the 1930s. Almost all of the previous studies of Malraux have focused on his literary life, and most of them are rife with errors. This dissertation focuses on the facts of his life, rather than on a fanciful recreation from his fiction. The major sources consulted are government documents, such as police reports and dispatches, the newspapers that Malraux founded with Paul Monin, other Indochinese and Parisian newspapers, and Malraux's speeches and interviews. Other sources include the memoirs of Clara Malraux, as well as other memoirs and reminiscences from people who knew Andre Malraux during the 1920s and the 1930s. The dissertation begins with a survey of Malraux's early years, followed by a detailed account of his experiences in Indochina. -

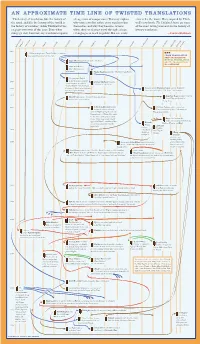

AN APPROXIMATE TIME LINE of TWISTED TRANSLATIONS “The History of Translation, Like the History of a Long Series of Compromises

AN APPROXIMATE TIME LINE OF TWISTED TRANSLATIONS “The history of translation, like the history of a long series of compromises. This may explain error is for the worse. Here, inspired by Thirl- the novel, and like the history of the world, is why some novelists refuse every translator but well’s new book, The Delighted States, are some the history of mistakes,” Adam Thirlwell writes themselves, and why they become anxious of the most vexing moments in the history of on page seventeen of this issue. Even when when their work must travel through a chain literary translation. things go well, however, any translation requires of languages to reach its public. But not every —Jascha Hoffman E N S E A N H I H H N N U N H H A C A S H S I C S A A H G A S I S N L I H H I I C I I I I B B L M S U D A A T C C N N S I T S N D U B A T G E R L S E R T L E N R R A D L R A E Z U N I R E E O O U P W I O A A C C C D E F F G P P P R S S Y Y 1490 KEY: A Valencian knight writes Tirant Lo Blanc in Catalan. CHAIN TRANSLATION It is finished by a friend after his death. SELF TRANSLATION Edgar Allan Poe publishes his poem “The Raven.” MUTUAL TRANSLATION 1850 GROUP TRANSLATION NO CATEGORY Lewis Carroll writes Alice’s Adventures in W onderland. -

Librairie Pierre PREVOST

Librairie Pierre PREVOST Liste n°46-1 – Petite bibliothèque littéraire 75, rue Michel-Ange Tel : 01 40 56 97 98 75016 PARIS Mob : 06 80 20 81 70 e-mail : [email protected] ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 01-BAINVILLE. Jacques. 180 € 03-BARRES. Maurice. 130 € Jaco et Lori. Dix jours en Italie. Paris. Grasset. 1927. 1 volume in-8 carré, demi- Paris. Crès. 1916. 1 volume in-16, demi-maroquin maroquin à coins bleu nuit, dos lisse, tête dorée. noirs à coins, plats bordés d’un double filet à froid, Couvertures et dos conservés. Reliure signée De dos lisse, tête dorée. Couvertures et dos conservés. Septime. 274 pp., (1) p. Reliure signée Greuzevault. Edition originale. 1 des 56 exemplaires numérotés sur Edition originale. vélin d’Arches. Exemplaire non rogné. 1 des 70 exemplaires numérotés sur japon impérial. Exemplaire à belles marges. Carnet de voyage en Italie pendant la Première Guerre 02-BARBIER. Auguste. 280 € mondiale. Ex-libris de Carlos Mayer, gravé par Stern ; timbre des Iambes. Librerias Martin Fierro. Paris. Urbain Canel et Ad. Guyot. 1832. 1 volume in-8, demi-veau glacé brun à coins, dos lisse orné et passé, couvertures conservées. Reliure signée 04-BENOIST-MECHIN. Jacques. 120 € Yseux Sr. de Simier. La musique et l’immortalité dans l’oeuvre de XXX pp., 144 pp., (1) p., 1 p. bl. Marcel Proust. Paris. Kra. 1926. 1 volume in-8 carré, demi- maroquin rouge, large bande centrale sur les plats, Edition originale des poèmes satiriques. tête dorée. Cette édition contient une préface, attribuée à Philarète Chasles, et deux pièces, Tentation et Couvertures et dos l’Iambe IX, qui ne seront pas reprises ensuite. -

Marcel Proust and the Global History of Asthma

Marcel Proust and the global history of asthma Professor Mark Jackson Centre for Medical History University of Exeter England Marcel Proust, 1871-1922 z born in Paris z Les Plaisirs et les Jours (1896) z À la recherche du temps perdu (1913-27) z Literary preoccupations with memory and guilt z Died from pneumonia Marcel Proust’s asthma z first attack, aged 9, walking in the Bois de Boulogne z regular, severe attacks of asthma and hay fever throughout his life, shaping his daily rhythms and dictating his creativity – slept during the day and worked at night z described in detail, particularly in letters to his mother Marcel Proust’s asthma `Ma chère petite Maman, An attack of asthma of unbelievable violence and tenacity – such is the depressing balance sheet of my night, which it obliged me to spend on my feet in spite of the early hour at which I got up yesterday.’ (c. 1900) `As soon as I reached Versailles I was seized with a horrifying attack of asthma, so that I didn’t know what to do or where to hide myself. From that moment to this the attack has continued.’ (26-8-1901) Marcel Proust’s asthma `Cher ami, I have been gasping for breath so continuously (incessant attacks of asthma for several days) that it is not very easy for me to write.’ (Letter to Marcel Boulenger, January 1920) Treating Proust’s asthma z Stramonium cigarettes `Ma chère petite maman, z Legras powders Yesterday after I wrote to you I z Espic powders had an asthma attack and incessant running at the nose, z Epinephrine which obliged me to walk all z Caffeine doubled up and light anti-asthma z Carbolic acid fumigations cigarettes at every tobacconist’s z Escouflaire powder as I passed, etc. -

CLAUDIA BAEZ Paintings After Proust

ART 3 109 Ingraham Street T 646 331 3162 Brooklyn NY 11237 www.art-3gallery.com FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE CLAUDIA BAEZ, PAINTINGS after PROUST Curated by Anne Strauss October 8 – November 22, 2014 Opening: Wednesday, October 8, 6 - 9 PM Claudia Baez, PAINTINGS after PROUST “And as she played, of all Albertine’s multiple tresses I could see but a single heart-shaped loop of black hair dinging to the side of her ear like the bow of a Velasquez Infanta.”, 2014, oil on canvas, 18 x 24 in. (45.7 x 61 cm.) © Claudia Baez Courtesy of ART 3 gallery Brooklyn, NY, September 19, 2014 – ART 3 opened in Bushwick in May 2014 near Luhring Augustine with its Inaugural Exhibition covered by The New York Times T Magazine, Primer. ART 3 was created by Silas Shabelewska-von Morisse, formerly of Haunch of Venison and Helly Nahmad Gallery. In July 2014, Monika Fabijanska, former Director of the Polish Cultural Institute in New York, joined ART 3 as Co-Director in charge of curatorial program, museums and institutions. ART 3 presents CLAUDIA BAEZ, PAINTINGS after PROUST on view at ART 3 gallery, 109 Ingraham Street, Bushwick, Brooklyn, from October 8 to November 22, 2014, Tue-Sat 12-6 PM. The opening will take place on Wednesday, October 8, from 6-9 PM. “In PAINTINGS after PROUST, Baez offers us an innovative chapter in contemporary painting in ciphering her art via a modernist work of literature within a postmodernist framework. […] In Claudia Baez’s exhibition literary narrative is poetically refracted through painting and vice versa, which the painter reminds us with artistic verve and aplomb of the adage that every picture tells a story as well as the other way around”. -

Memory, Time and Identity in the Novels of William Faulkner and Marcel Proust

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 2000 Memory, Time and Identity in the Novels of William Faulkner and Marcel Proust. John Stephen Larose Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Larose, John Stephen, "Memory, Time and Identity in the Novels of William Faulkner and Marcel Proust." (2000). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 7206. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/7206 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. -

The Scientific Background of the International Sanitary Conferences

The scientific background of the International Sanitary Conferences Norman Howard-Jones h 4 "1 Formerly Director, Division of Editorial and Reference Services, World Health Organization WORLD HEALTH ORGANIZATION GENEVA 1975 HISTORY OF INTERNATIONAL PUBLIC HEALTH, No. 1 This study originally appeared in WHO Chronicle, 1974, 28, 159-171, 229-247, 369-348, 414-426, 455-470, 495-508. 0 World Health Organization 1975 Publications of the World Health Organization enjoy copyright protection in accord- ance with provisions of Protocol 2 of the Universal Copyright Convention. For rights of reproduction or translation of WHO publications in part or in toto, application should be made to the Division of Publications and Translation, World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland. The World Health Organization welcomes such applications. The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Director-General of the World Health Organization concerning the legal status of any country or territory or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers. The author alone is responsible for the views expressed in this publication. l1 CONTENTS Page Preface ............................... 7 Introduction ............................. 9 The first conference : Paris. 1851 .................... 12 The second conference : Paris. 1859 .............. ..... 17 The third conference : Constantinople. 1866 ............... 23 The fourth conference : Vienna. 1874 .................. 35 The fifth conference : Washington. 188 1 ............ ..... 42 The sixth conference : Rome. 1885 .............. ..... 46 The seventh conference . Venice. 1892 ............. ..... 58 The eighth conference : Dresden. 1893 ............ ..... 66 The ninth conference : Paris. 1894 ................... 71 The tenth conference: Venice. 1897 .............. ..... 78 The eleventh conference : Paris. 1903 ................. -

International Sanitary Conferences from the Ottoman Perspective (1851–1938)

International Sanitary Conferences from the Ottoman perspective (1851–1938) Nermin Ersoy, Yuksel Gungor and Aslihan Akpinar Introduction The backdrop to the epidemics of the nineteenth century was the Industrial Revolution with the rapid increase of the urban population, unsanitary settle- ments in the vicinity of factories, long working hours and deterioration of living conditions for workers, malnutrition and the failure of nation-states to meet these challenges.1 The acceleration of transport due to the invention of steam- ships (1810) and the railway (1830) and the extension of international trade and pilgrimage via the Suez Channel (1869), as well as huge waves of migration from Europe to America led to the outbreak of the contagious diseases.2 Plague followed by other contagious diseases like cholera, typhus and tuber- culosis were also exposed to Ottoman Land from the beginning of the nineteenth century to the beginning of the twentieth. In the first part of this era initiating the quarantine measures in Ottoman World was highly grueling because of protes- tations by the ulema (religious clergy) to whom diseases were the scourge of God on his unruly subjects. However with the pressure of the European powers, both quarantines and the other necessities enforced by them had been adminis- 1 Simon Szreter, “Industrialization and Health”, British Medical Bulletin, 69 (2004), 75–86.; Marie-France Morel, “The Care of Children: The Influence of Medical Innovation and Medical Institutions on Infant Mortality 1750–1914”, in R. Schofield, D. Reher, and A. Bideau, eds., The Decline of Mortality in Europe, (Oxford Clarendon Press, 1991), pp. 196– 220.: Edwin Chadwick, “Report on the sanitary condition of the labouring population and on the means of its improvement”, London May 1842, http://www.deltaomega.org/ ChadwickClassic.pdf, (accessed February 04, 2010); Bekir Metin and Sevim T.