Judges and The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Licensing Act 2003 (C

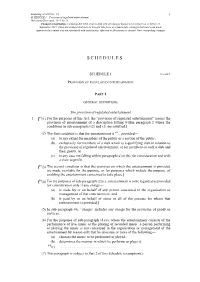

Licensing Act 2003 (c. 17) 1 SCHEDULE 1 – Provision of regulated entertainment Document Generated: 2021-09-13 Changes to legislation: Licensing Act 2003 is up to date with all changes known to be in force on or before 13 September 2021. There are changes that may be brought into force at a future date. Changes that have been made appear in the content and are referenced with annotations. (See end of Document for details) View outstanding changes SCHEDULES SCHEDULE 1 Section 1 PROVISION OF REGULATED ENTERTAINMENT PART 1 GENERAL DEFINITIONS The provision of regulated entertainment 1 [F1(1) For the purposes of this Act, the “provision of regulated entertainment” means the provision of entertainment of a description falling within paragraph 2 where the conditions in sub-paragraphs (2) and (3) are satisfied.] (2) The first condition is that the entertainment is F2... provided— (a) to any extent for members of the public or a section of the public, (b) exclusively for members of a club which is a qualifying club in relation to the provision of regulated entertainment, or for members of such a club and their guests, or (c) in any case not falling within paragraph (a) or (b), for consideration and with a view to profit. [F3(3) The second condition is that the premises on which the entertainment is provided are made available for the purpose, or for purposes which include the purpose, of enabling the entertainment concerned to take place.] [F4(4) For the purposes of sub-paragraph (2)(c), entertainment is to be regarded as provided for consideration only if any charge— (a) is made by or on behalf of any person concerned in the organisation or management of that entertainment, and (b) is paid by or on behalf of some or all of the persons for whom that entertainment is provided.] (5) In sub-paragraph (4), “charge” includes any charge for the provision of goods or services. -

Groups, Governance and the Development of UK Alcohol Policy: an Adversarial Policy Communities Approach

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Online Repository of Birkbeck Institutional Theses Groups, governance and the development of UK alcohol policy: An Adversarial Policy Communities Approach Gareth Paul Barrett A thesis presented for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Politics Birkbeck, University of London January 2020 1 Declaration of Work I certify that the thesis I have presented for examination for the PhD degree of the University of London is solely my own work other than where I have clearly indicated that it is the work of others. The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. Quotation from it is permitted, provided that full acknowledgement is made. This thesis may not be reproduced without my prior written consent. 2 Abstract The governance of UK alcohol policy looks like a textbook case of decision-making by a closed community of policymakers and industry insiders, but this thesis challenges this view. Drawing on Jordan and Richardson’s policy communities approach and Dudley and Richardson’s later work on adversarial policy communities, it examines the complex development of UK alcohol policy using archival sources, government and pressure group reports, news releases and historic media coverage going back over a century. The primary focus of this research is Westminster, but the importance of subnational policy communities is also considered through an examination of Scottish alcohol policy development. Through case studies of four key areas of UK alcohol policy – licensing, drink- driving, pricing and wider alcohol strategies – this thesis finds that the governance of UK alcohol policy is formed within policy communities, but ones that are much less closed and much more adversarial than traditionally thought. -

Groups, Governance and the Development of UK Al- Cohol Policy: an Adversarial Policy Communities Ap- Proach

ORBIT-OnlineRepository ofBirkbeckInstitutionalTheses Enabling Open Access to Birkbeck’s Research Degree output Groups, governance and the development of UK al- cohol policy: an adversarial policy communities ap- proach https://eprints.bbk.ac.uk/id/eprint/40473/ Version: Full Version Citation: Barrett, Gareth Paul (2020) Groups, governance and the de- velopment of UK alcohol policy: an adversarial policy communities ap- proach. [Thesis] (Unpublished) c 2020 The Author(s) All material available through ORBIT is protected by intellectual property law, including copy- right law. Any use made of the contents should comply with the relevant law. Deposit Guide Contact: email Groups, governance and the development of UK alcohol policy: An Adversarial Policy Communities Approach Gareth Paul Barrett A thesis presented for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Politics Birkbeck, University of London January 2020 1 Declaration of Work I certify that the thesis I have presented for examination for the PhD degree of the University of London is solely my own work other than where I have clearly indicated that it is the work of others. The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. Quotation from it is permitted, provided that full acknowledgement is made. This thesis may not be reproduced without my prior written consent. 2 Abstract The governance of UK alcohol policy looks like a textbook case of decision-making by a closed community of policymakers and industry insiders, but this thesis challenges this view. Drawing on Jordan and Richardson’s policy communities approach and Dudley and Richardson’s later work on adversarial policy communities, it examines the complex development of UK alcohol policy using archival sources, government and pressure group reports, news releases and historic media coverage going back over a century. -

Abolishing the Crime of Public Nuisance and Modernising That of Public Indecency

International Law Research; Vol. 6, No. 1; 2017 ISSN 1927-5234 E-ISSN 1927-5242 Published by Canadian Center of Science and Education Abolishing the Crime of Public Nuisance and Modernising That of Public Indecency Graham McBain1,2 1 Peterhouse, Cambridge, UK 2 Harvard Law School, USA Correspondence: Graham McBain, 21 Millmead Terrace, Guildford, Surrey GU2 4AT, UK. E-mail: [email protected] Received: November 20, 2016 Accepted: February 19, 2017 Online Published: March 7, 2017 doi:10.5539/ilr.v6n1p1 URL: https://doi.org/10.5539/ilr.v6n1p1 1. INTRODUCTION Prior articles have asserted that English criminal law is very fragmented and that a considerable amount of the older law - especially the common law - is badly out of date.1 The purpose of this article is to consider the crime of public nuisance (also called common nuisance), a common law crime. The word 'nuisance' derives from the old french 'nuisance' or 'nusance' 2 and the latin, nocumentum.3 The basic meaning of the word is that of 'annoyance';4 In medieval English, the word 'common' comes from the word 'commune' which, itself, derives from the latin 'communa' - being a commonality, a group of people, a corporation.5 In 1191, the City of London (the 'City') became a commune. Thereafter, it is usual to find references with that term - such as common carrier, common highway, common council, common scold, common prostitute etc;6 The reference to 'common' designated things available to the general public as opposed to the individual. For example, the common carrier, common farrier and common innkeeper exercised a public employment and not just a private one. -

Criminal Justice and Police Act 2001 Is up to Date with All Changes Known to Be in Force on Or Before 08 September 2021

Changes to legislation: Criminal Justice and Police Act 2001 is up to date with all changes known to be in force on or before 08 September 2021. There are changes that may be brought into force at a future date. Changes that have been made appear in the content and are referenced with annotations. (See end of Document for details) View outstanding changes Criminal Justice and Police Act 2001 2001 CHAPTER 16 An Act to make provision for combatting crime and disorder; to make provision about the disclosure of information relating to criminal matters and about powers of search and seizure; to amend the Police and Criminal Evidence Act 1984, the Police and Criminal Evidence (Northern Ireland) Order 1989 and the Terrorism Act 2000; to make provision about the police, the National Criminal Intelligence Service and the National Crime Squad; to make provision about the powers of the courts in relation to criminal matters; and for connected purposes. [11th May 2001] Be it enacted by the Queen’s most Excellent Majesty, by and with the advice and consent of the Lords Spiritual and Temporal, and Commons, in this present Parliament assembled, and by the authority of the same, as follows:— PART 1 PROVISIONS FOR COMBATTING CRIME AND DISORDER CHAPTER 1 ON THE SPOT PENALTIES FOR DISORDERLY BEHAVIOUR Modifications etc. (not altering text) C1 Pt. 1 Ch. 1 extended (15.11.2003) by Police Reform Act 2002 (c. 30), ss. 38, 108, Sch. 4 para. 1(2)(a); S.I. 2003/2593, art. 2(d) C2 Pt. 1 Ch. 1 modified (26.12.2004) by The Penalties for Disorderly Behaviour (Amendment of Minimum Age) Order 2004 (S.I. -

Trust and Fiduciary Duty in the Early Common Law

TRUST AND FIDUCIARY DUTY IN THE EARLY COMMON LAW DAVID J. SEIPP∗ INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................. 1011 I. RIGOR OF THE COMMON LAW ........................................................... 1012 II. THE MEDIEVAL USE .......................................................................... 1014 III. ENFORCEMENT OF USES OUTSIDE THE COMMON LAW ..................... 1016 IV. ATTENTION TO USES IN THE COMMON LAW ..................................... 1018 V. COMMON LAW JUDGES AND LAWYERS IN CHANCERY ...................... 1022 VI. FINDING TRUST IN THE EARLY COMMON LAW ................................. 1024 VII. THE ATTACK ON USES ....................................................................... 1028 VIII. FINDING FIDUCIARY DUTIES IN THE EARLY COMMON LAW ............. 1034 CONCLUSION ................................................................................................. 1036 INTRODUCTION Trust is an expectation that others will act in one’s own interest. Trust also has a specialized meaning in Anglo-American law, denoting an arrangement by which land or other property is managed by one party, a trustee, on behalf of another party, a beneficiary.1 Fiduciary duties are duties enforced by law and imposed on persons in certain relationships requiring them to act entirely in the interest of another, a beneficiary, and not in their own interest.2 This Essay is about the role that trust and fiduciary duty played in our legal system five centuries ago and more. -

![Magna Carta Commemoration Essays [1917]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5019/magna-carta-commemoration-essays-1917-2255019.webp)

Magna Carta Commemoration Essays [1917]

The Online Library of Liberty A Project Of Liberty Fund, Inc. Henry Elliot Malden, Magna Carta Commemoration Essays [1917] The Online Library Of Liberty This E-Book (PDF format) is published by Liberty Fund, Inc., a private, non-profit, educational foundation established in 1960 to encourage study of the ideal of a society of free and responsible individuals. 2010 was the 50th anniversary year of the founding of Liberty Fund. It is part of the Online Library of Liberty web site http://oll.libertyfund.org, which was established in 2004 in order to further the educational goals of Liberty Fund, Inc. To find out more about the author or title, to use the site's powerful search engine, to see other titles in other formats (HTML, facsimile PDF), or to make use of the hundreds of essays, educational aids, and study guides, please visit the OLL web site. This title is also part of the Portable Library of Liberty DVD which contains over 1,000 books and quotes about liberty and power, and is available free of charge upon request. The cuneiform inscription that appears in the logo and serves as a design element in all Liberty Fund books and web sites is the earliest-known written appearance of the word “freedom” (amagi), or “liberty.” It is taken from a clay document written about 2300 B.C. in the Sumerian city-state of Lagash, in present day Iraq. To find out more about Liberty Fund, Inc., or the Online Library of Liberty Project, please contact the Director at [email protected]. -

The Common Law: an Account of Its Reception in the United States

Vanderbilt Law Review Volume 4 Issue 4 Issue 4 - June 1951 Article 3 6-1951 The Common Law: An Account of its Reception in the United States Ford W. Hall Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.vanderbilt.edu/vlr Part of the Common Law Commons, and the Courts Commons Recommended Citation Ford W. Hall, The Common Law: An Account of its Reception in the United States, 4 Vanderbilt Law Review 791 (1951) Available at: https://scholarship.law.vanderbilt.edu/vlr/vol4/iss4/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship@Vanderbilt Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Vanderbilt Law Review by an authorized editor of Scholarship@Vanderbilt Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE COMMON LAW: AN ACCOUNT OF ITS RECEPTION IN THE UNITED STATES FORD W. HALL* "The common law of England is not to be taken, in all respects, to be that of America. Our ancestors brought with them its general principles, and claimed it as their birth- right; but they brought with them and adopted only that portion which was applicable to their situation." Story, J., in Van Ness v. Pacard, 2 Pet. 137, 144, 7 L. Ed. 374 (1829). The story of the extent to which the common law of England has been received and applied in the United States, is one of the most interesting and important chapters in American legal history. However, many courts and writers have shown a tendency simply to say that our colonial forefathers brought the common law of England with them, and there has often been little or no inclination to look further into the question. -

Commentaries on American Law, Vol. 4 (1830)

COMMENTARIES ON AMERICAN LAW BOOK 4 (1830) JAMES KENT Based on the first edition Footnotes have been converted to chapter end notes. Spelling has been modernized. This electronic edition © Copyright 2006 Lonang Institute www.lonang.com Table of Contents PART 6 (con’t.) - Of the Law Concerning Real Property: Lect. 53: Of Estates In Fee................................................... 2 Lect. 54: Of Estates for Life.................................................. 14 Lect. 55: Of Estates for Years, at Will, or at Sufferance ............................ 46 Lect. 56: Of Estates upon Condition ............................................ 64 Lect. 57: Of the Law of Mortgage ............................................. 71 Lect. 58: Of Estates in Remainder ............................................. 103 Lect. 59: Of Executory Devises ............................................... 137 Lect. 60: Of Uses and Trusts ................................................. 150 Lect. 61: Of Powers ........................................................ 162 Lect. 62: Of Estates in Reversion.............................................. 181 Lect. 63: Of a Joint Interest in Land............................................ 183 Lect. 64: Of Title by Descent ................................................. 191 Lect. 65: Of Title by Escheat, by Forfeiture, and by Execution ....................... 215 Lect. 66: Of Title by Deed ................................................... 222 Lect. 67: Of Title by Will or Devise ........................................... -

Bibliography

BIBLIOGRAPHY Ackroyd, P. (1991). Charles Dickens. London: Methuen. Adams, E. (2011). Liberal Epic: The Victorian Practice of History from Gibbon to Churchill. Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press. Aldous, R. (2007). The Lion and the Unicorn: Gladstone v Disraeli. London: Pimlico. Allan, T. (1993). Law, Liberty and Justice. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Allan, T. (2001). Constitutional Justice: A Liberal Theory of the Rule of Law. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Allison, J. (2007). The English Historical Constitution: Continuity, Change and European Effects. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Alter, R. (1968). The Demons of History in Dickens, Tale. Novel, 2, 135–142. Anderson, A. (2007). Trollope’s Modernity. ELH, 74, 509–534. Anderson, O. (1967). The Political Uses of History in Mid Nineteenth Century England. Past and Present, 36, 87–105. Arnold, M. (1968). Essays in Criticism. Chicago: Chicago University Press. Arnold, M. (1986). Matthew Arnold: A Critical Edition of the Major Works. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Arnold, M. (1993). Culture and Anarchy, and Other Writings. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Arnstein, W. (1962). Gladstone and the Bradlaugh Case. Victorian Studies, 5, 303–330. Arnstein, W. (2003). Queen Victoria. Basingstoke: Palgrave. Bagehot, W. (1965). The Collected Works of Walter Bagehot (St. John Stevas, Ed.). London: The Economist. © The Editor(s) (if applicable) and The Author(s), 195 under exclusive license to Springer International Publishing AG, part of Springer Nature 2018 I. Ward, Writing the Victorian Constitution, Palgrave Modern Legal History, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-96676-2 196 BIBLIOGRAPHY Bagehot, W. (2001). The English Constitution. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Balfour, A. (1928). -

Serious Organised Crime and Police Act 2005

Status: This version of this Act contains provisions that are prospective. Changes to legislation: There are outstanding changes not yet made by the legislation.gov.uk editorial team to Serious Organised Crime and Police Act 2005. Any changes that have already been made by the team appear in the content and are referenced with annotations. (See end of Document for details) View outstanding changes Serious Organised Crime and Police Act 2005 2005 CHAPTER 15 An Act to provide for the establishment and functions of the Serious Organised Crime Agency; to make provision about investigations, prosecutions, offenders and witnesses in criminal proceedings and the protection of persons involved in investigations or proceedings; to provide for the implementation of certain international obligations relating to criminal matters; to amend the Proceeds of Crime Act 2002; to make further provision for combatting crime and disorder, including new provision about powers of arrest and search warrants and about parental compensation orders; to make further provision about the police and policing and persons supporting the police; to make provision for protecting certain organisations from interference with their activities; to make provision about criminal records; to provide for the Private Security Industry Act 2001 to extend to Scotland; and for connected purposes. [7th April 2005] BE IT ENACTED by the Queen's most Excellent Majesty, by and with the advice and consent of the Lords Spiritual and Temporal, and Commons, in this present Parliament assembled, and by the authority of the same, as follows:— F1 PART 1 THE SERIOUS ORGANISED CRIME AGENCY Textual Amendments F1 Pt. 1 omitted (7.10.2013) by virtue of Crime and Courts Act 2013 (c. -

The Rise of the Burwells

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 1959 The Rise of the Burwells John L. Blair College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Blair, John L., "The Rise of the Burwells" (1959). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539624513. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-2e74-qc60 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. tm rise of tm wmmm A thesis Present** to fh* Futility of tfi# Dep&tmni of History th* College of Willis* and Mary Xn Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts fey John t. Biair 1959 APPROVAL $H8tf This thesis is mfo«£&$*& in. partial fulfillment #1 ths rs^itiiMnii# ffcf th* 6*gr«o of Master of Arts "Q 9 ^ t i ^ < > y Aotfcor A$p*ots4i fgagios Ifpryjsii'' ftffith liMiiU MiJi'H» wrJKWWiOSSSSj^^ n nw*w mm Richard is* Morton, Fh*0 TABLE OF COHlSSfS Fags Preface......... V Chapter X The Early Years .................. 1 Chapter IX Expansion and Consolidation * * * # . • , • . 14 Chapter III Tha Third 6anaratlon . ................... 40 Susmary •••••••< 76 Bibliography . ♦ . ........... 80 little olf ,f6oti#,, PRErACB the Btirvell* aaong the loafers ©I colonial Virginia !«r orer * century* for n m # years they tut in tha house of Burgas*** an© upon the Council* they serte© ©a mwvtrout special eeawiCteeSt which in note cases were form*! ■for specific purposes avsh as to *i© in eh* renewal if the coital l ^ s Jattstowa to WlUiaashurg or to help in eh* astabHabnsnt; of * school of higher learning.