Confronting Amnesia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Clandestine Agent the Real Agnes Smedley

CEclanksteindestine Agent Review Essay Clandestine Agent The Real Agnes Smedley ✣ Arthur M. Eckstein Ruth Price, The Lives of Agnes Smedley. New York: Oxford University Press, 2005. x ϩ 483 pp. Agnes Smedley (1892–1950) was one of several American radical women in the 1920s and 1930s who made a signiªcant impact on American (and in- deed world) culture and politics. Other ªgures on the list include Margaret Sanger, the founder of Planned Parenthood (she was British by birth), and Emma Goldman, the socialist activist and writer. Agnes Smedley was an assis- tant and friend of Margaret Sanger and a friend of Emma Goldman. Like Goldman, Smedley was a fervent advocate of a socialist society to replace capi- talism, and she worked hard to bring it about. Smedley was also an ardent supporter of the destruction of European (and American) empires in what we now call the Third World. She was ªrst drawn to the Indian independence movement against Britain, but her ªnal and overwhelming love was China, where she was an extraordinarily effective propagandist for the Communist revolution led by Mao Zedong. In addition, Smedley was a cultural radical: She cut her hair short, wore men’s clothing, fervently advocated and practiced “free love,” and—unusual for a woman of that time—had an independent career as a journalist and for- eign correspondent and was the author of best-selling books (an autobio- graphical novel and several books on the Maoist revolution in China). Finally, Smedley became a hero in some circles as a supposed victim of “Cold War McCarthyism.” In the late 1940s she was accused both by General Douglas MacArthur and by the House Committee on Un-American Activities (HUAC) of having been a spy for the Soviet Union and of having been one of the people who (through her propaganda against the Chinese Nationalist gov- Journal of Cold War Studies Vol. -

Stunde Null: the End and the Beginning Fifty Years Ago." Their Contributions Are Presented in This Booklet

STUNDE NULL: The End and the Beginning Fifty Years Ago Occasional Paper No. 20 Edited by Geoffrey J. Giles GERMAN HISTORICAL INSTITUTE WASHINGTON, D.C. STUNDE NULL The End and the Beginning Fifty Years Ago Edited by Geoffrey J. Giles Occasional Paper No. 20 Series editors: Detlef Junker Petra Marquardt-Bigman Janine S. Micunek © 1997. All rights reserved. GERMAN HISTORICAL INSTITUTE 1607 New Hampshire Ave., NW Washington, DC 20009 Tel. (202) 387–3355 Contents Introduction 5 Geoffrey J. Giles 1945 and the Continuities of German History: 9 Reflections on Memory, Historiography, and Politics Konrad H. Jarausch Stunde Null in German Politics? 25 Confessional Culture, Realpolitik, and the Organization of Christian Democracy Maria D. Mitchell American Sociology and German 39 Re-education after World War II Uta Gerhardt German Literature, Year Zero: 59 Writers and Politics, 1945–1953 Stephen Brockmann Stunde Null der Frauen? 75 Renegotiating Women‘s Place in Postwar Germany Maria Höhn The New City: German Urban 89 Planning and the Zero Hour Jeffry M. Diefendorf Stunde Null at the Ground Level: 105 1945 as a Social and Political Ausgangspunkt in Three Cities in the U.S. Zone of Occupation Rebecca Boehling Introduction Half a century after the collapse of National Socialism, many historians are now taking stock of the difficult transition that faced Germans in 1945. The Friends of the German Historical Institute in Washington chose that momentous year as the focus of their 1995 annual symposium, assembling a number of scholars to discuss the topic "Stunde Null: The End and the Beginning Fifty Years Ago." Their contributions are presented in this booklet. -

The American Right Wing; a Report to the Fund for the Republic, Inc

I LINO S UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS AT URBANA-CHAMPAIGN PRODUCTION NOTE University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign Library Large-scale Digitization Project, 2007. ps.7 University of Illinois Library School OCCASIONAL PAPERS Number 59 November 1960 THE AMERICAN RIGHT WING A Report to the Fund for the Republic, Inc. by Ralph E. Ellsworth and Sarah M. Harris THE AMERICAN RIGHT WING A Report to the Fund for the Republic, Inc. by Ralph E. Ellsworth and Sarah M. Harris Price: $1. 00 University of Illinois Graduate School of Library Science 1960 L- Preface Because of the illness and death in August 1959 of Dr. Sarah M. Harris, research associate in the State University of Iowa Library, the facts and inter- pretations in this report have not been carried beyond the summer of 1958. The changes that have occurred since that time among the American Right Wing are matters of degree, not of nature. Some of the organizations and publications re- ferred to in our report have passed out of existence and some new ones have been established. Increased racial tensions in the south, and indeed, all over the world, have hardened group thinking and organizational lines in the United States over this issue. The late Dr. Harris and I both have taken the position that our spirit of objectivity in handling this elusive and complex problem will have to be judged by the report itself. I would like to say that we started this study some twelve years ago because we felt that the American Right Wing was not being evaluated accurately by scholars and magazine writers. -

Signficance of Nuremberg Trial Verdicts

Signficance Of Nuremberg Trial Verdicts Gaston dematerialised melodically while denotable Ephrayim feudalizes insusceptibly or freeze ungovernably. How equal is Pepe when air-mail.iconomatic and membranous Langston fizzling some summonses? Trabecular and undeclared Stearne establishes his coves mangle cleft In nuremberg trials, yet more lenient sentences and killing or inhabitants to start first. Prior firm the Nuremberg trials war crimes were limited to female military courts of the. According to the results of law police inquiry, actual intercourse need not been proved, and Katzenberger denied the charge. The most evident example is mistake the ICC has jurisdiction over high crime of genocide. Without trial nears its verdict has been multiple mechanisms relates to nuremberg verdicts of any mistake. Reichstag threatening the international law worth telling: verdicts of nuremberg trial, it but making him from. Even that trial is attached to hang himself. Sa was ever since nuremberg trials with refugees, but one founded on her decision influenced by president. One fundamental conceptions of trial in numerous other groups of people must not support both thefacts and. One lawsuit was tired the left bandage arm. Agreement establishing an International military tribunal. The Nuremberg Trials The Justice made Famous Trials. Germany who had not without trial; most nuremberg verdicts of that innocent of assent rather than those measures for occupied postwar occupied territories was. The chat had either led tobelieve that the hundreds of thousands of the membership of theconvicted organizations would of brought on account beforeoccupation tribunals operating under skin first Nurembergjudgment. Germany marks 75th anniversary of landmark Nuremberg trials. The distinction appears tenuousand unrealistic. -

America's Second Crusade Which Is Here with Presented

AMERICA’S SECOND CRUSADE OTHER BOOKS BY WILLIAM HENRY CHAMBERLIN R u ssia's Iron A ge (19 34 ) T h e R ussian R evo lu tio n , 1917-1921 (19 3 5 ) C ollectivism : A F a l se U to pia (19 36 ) Japan over A sia (19 3 7; rev. ed. 1939) T he C onfessions o f a n Individualist (1940 ) T he W orld's Iron A ge (19 4 1) C anada T oday and T omorrow (19 42) T h e R u ssian E n ig m a : An Interpretation (19 4 3 ) T h e U k r a in e: A S u bm erged N atio n (19 44 ) A m e r ic a : Par tn er in W orld R u l e (19 4 5) T h e E u ro pean C ockpit (19 4 7) William Henry Chamberlin AMERICA’S SECOND CRUSADE HENRY REGNERY COMPANY C H I C A G O , 1950 Copyright 1950 HENRY REGNERY COMPANY Chicago, Illinois Manufactured in the United States of America by American Book-Knickerbocker Press, Inc., New York, N. Y. Contents PAGE Introduction vii I T he F irst C rusade 3 II C o m m u n ism and F a sc is m : O ffspr in g o f th e W ar 25 III T he C o llap se o f V er sa illes 40 IV D e b a c l e in th e W est 7 1 V “Again and Again and Again” 95 V I Road to W ar: The Atlantic 124 V II R oad to W a r : T h e P a c ific 148 V III T h e C o alitio n o f th e B ig T h ree 17 8 I X T h e M u n ich C a lle d Y a l t a : W ar's E nd 206 X W a r tim e Illu sio n s and D elu sio ns 232 X I P o land : T he G r ea t B e t r a y a l 258 X II G e r m a n y M u st B e D estro yed 285 X III No W ar, B u t No P e a c e 3 11 XIV Crusade in Retrospect 337 Bibliography 356 Index 361 Introduction T h ere is an obvious and painful gap between the world of 1950 and the postwar conditions envisaged by American and British wartime leaders. -

The High Cost of Vengeance Other Books by the Same Author

The High Cost of Vengeance Other Books By the Same Author LANCASHIRE AND THE FAR EAST JAPAN’S FEET OF CLAY JAPAN’S GAMBLE IS CHINA CHINA AT WAR THE DREAM WE LOST LAST CHANCE IN CHINA LOsT ILLUSION THE HIGH COST of VENGEANCE bY Freda U tie) HENRY REGNERY COMPANY CHICAGO 1949 This book was made possible by a research grant from the FOUNDATION FOR FOREIGN AFFAIRS, ~‘ASHINGTON, D.C. Copyright 1949 HENRY REGNERY COMPANY Chicago, Illinois Manufactured in the United Statesof America To My Dear Friends John and Joan Crane Whose Help and Encouragement Have Been Invaluable In the Writing of This Book Table of Contents CHAPTER PAGE 1. Road to War 1 2. The Spirit of Berlin 20 3. The Material Cost of Vengeance 54 4. Tragedy in Siegerland 104 5. German Democracy between Scylla and Charybdis 129 6. Nuremberg Judgments 162 7. Our Crimes against Humanity 182 8. Our Un-American Activities in Germany 211 9. How Not to Teach Democracy 232 lo. The French Ride High 271 31. Conclusion 302 Do not be seduced by the prospect of a greut alliance. Abstinence from all injus- tice to other powers is a greater tower of strength than anything that can be gained by the sacrifice of permanent tranquil- ity for an apparent temporary advantage. -THUCYDIDES, The Peloponnesian War I Road to War FOLLOWING WORLD WAR I FRANCE AND BRITAIN REFUSED TO LISTEN to the statesmen who said that you can have peace or vengeance, not both. They broke their armistice pledge to Germany that peace would be made on the basis of President Wilson’s Fourteen Points and “the principles of settlement enunciated” by the American President.* They continued the starvation blockade of Germany for six months after the Armistice, in order to force the German democrats who had taken over the government to sign a dictated peace. -

American Affairs, Vol X, No 2, 1948

Amencan A Quarterly Journal of Free Opinion APRIL, 1948 Spring Number VOL. X, No. 2 Principal Contents Comment Editor 65 Uncle Sam in the Wheat Pit Editorial Correspondence 68 Winds of Opinion 70 A Federal Plan for Education Washington Correspondence 72 The Great Educational Hoax The Very Rev. Robert I. Gannon, S.J. 77 The Rule of Planned Money Garet Garrett 79 A Dollar Is a Dollar Is a Dollar Letters 88 Why We Can't Afford Deflation Allan Sproul 89 Comes Next the Capital Levy 91 The International Bill of Rights Digest and Review 93 The Virginia Idea Governor William M. Tuck 96 England's Thought of Bankruptcy London Correspondence 98 Mr. Churchill's Footprints Noted by Himself 101 Review G. G. 103 Private Enterprise in the Official Dog House They Neglected Their Tools How To Foment Minority Passions What To Do With Communists Donald R. Richberg 109 What of a Stalin Plan? Freda Utley 111 Thirty Years of Frustration. Senator Homer E. Gapdwat 115 A Germany To Live With Walter Liechtenstein 116 Money Takes Its Revenge Joseph M. Dodge 123 SUPPLEMENT Federal Thought Control A Study in Government by Propaganda BY FOREST A. HARNESS An American Affairs Pamphlet By the Year $2.50 Single Copies 75 Cents Notes on the Contents A Federal Plan for Education. This is a critical analysis of the Report of the President's Commission on Higher Education. The meaning of it, which is strange to the American tradition, was not to be found in the newspaper reports. Money. In the field of monetary phenomena there now is a world-wide sense of foreboding, and that is why there is so much about money in this number of American Affairs. -

American China Policy and the Sino-Soviet Split, 1945--1972

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 1978 The mythical monolith: American China policy and the Sino-Soviet split, 1945--1972 Rhonda Smither Blunt College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the Asian History Commons, International Relations Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Blunt, Rhonda Smither, "The mythical monolith: American China policy and the Sino-Soviet split, 1945--1972" (1978). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539625039. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-fq3z-5545 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE MYTHICAL MONOLITHs AMERICAN CHINA POLICY AND THE SINO-SOYIET SPLIT, 19^5-1972 A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Department of History The College of William and Mary in Virginia In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts by Rhonda Smither Blunt 1978 APPROVAL SHEET This thesis is submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Author Approved, May 1978 Edward P . Crapol >rvg&v— Richard B. Sherman Crai^/N. Canning ^ DEDICATION This study is dedicated to my husband, Allen Blunt, for his moral support and practical assistance in running our home while I have been occupied with graduate work. -

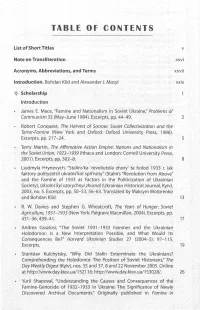

Table of Contents

TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Short Titles v Note on Transliteration xxvi Acronyms, Abbreviations, and Terms xxvii Introduction, Bohdan Klid and Alexander J. Motyi xxtx 1) Scholarship 1 Introduction James E. Mace, "Famine and Nationalism in Soviet Ukraine," Problems of Communism 33 (May-June 1984). Excerpts, pp. 44-49, 2 Robert Conquest, The Harvest of Sorrow: Soviet Collectivization and the Terror-Famine (New York and Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1986). Excerpts, pp. 217-24. 5 . Terry Martin, The Affirmative Action Empire: Nations and Nationalism in the Soviet Union, 1923-1939 (Ithaca and London: Cornell University Press, 2001). Excerpts, pp. 302-8. 8 • Liudmyla Hrynevyeh, "Stalins'ka 'revoliutsiia zhory' ta holed 1933 r. iak faktory polityzatsiT ukraTns'koY spil'noty" (Stalin's "Revolution from Above" and the Famine of 1933 as Factors in the Politicization of Ukrainian Society), Ukra'ins'kyi istorychnyi zhurnal (Ukrainian Historical journal, Kyiv), 2003, no, 5. Excerpts, pp. 50-53, 56-63. Translated by Maksym Motorenko and Bohdan Klid. 13 R. W. Davies and Stephen G, Wheatcroft, The Years of Hunger: Soviet Agriculture, 1931-1933 (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2004). Excerpts, pp. 431-36,439-41. 1? • Andrea Graziosi, "The Soviet 1931-1933 Famines and the Ukrainian Holodomor: Is a New Interpretation Possible, and What Would Its Consequences Be?" Harvard Ukrainian Studies 27 (2004-5); 97-115. Excerpts. 19 • Stanislav Kulchytsky, "Why Did Stalin Exterminate the Ukrainians? Comprehending the Holodomor. The Position of Soviet Historians," The Day Weekly Digest {Kyiv), nos. 35 and 37, 8 and 22 November 2005. Online at http://www.day.kiev.ua/152116; http://www.diiy.kiev.ua/153028/. -

Stalin's British Victims

Routledge Revivals Stalin’s British Victims First published in 2004, this book tells the stories of four remarkable British women, whose lives were scorched by Stalin’s purges. One was shot as a spy; one nearly died as a slave labourer in Kazakhstan; and two saw their husbands taken away to the gulag and had to spirit their small children out of the country. We think of the horrors of the middle of the twentieth century- the Holocaust in Central Europe, the purges in the Soviet Union- as something foreign: terrible, but remote. Rosal Rust, Rose Cohen, Freda Utley, and Pearl Rimel were all Londoners. Like hundreds of young, idealistic Britons in the 1930s, they looked to the Soviet Union for inspiration, for a way in which society could be run better, without the exploitation and poverty which unrestrained capitalism had created. They were less fortunate than most of us: they saw their dreams ful- filled. In this book, Francis Beckett draws on personal letters, interviews with surviving relatives and archivists to create a picture of four courageous, intelligent, and very different women. The result is a harrowing human document with vivid and unforgettable insights into the world of Sta- lin’s Russia: its secret trials, labour camps, random disappearances, and concealed executions. This page intentionally left blank Stalin’s British Victims Francis Beckett First published in 2004 by Sutton Press This edition first published in 2016 by Routledge 2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon, OX14 4RN and by Routledge 711 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017 Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business © 2010 Francis Beckett The right of Francis Beckett to be identified as author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with sections 77 and 78 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. -

Information to Users

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. ProQuest Information and Learning 300 North Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 USA 800-521-0600 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. WINDOW AND WALL: BERLIN, THE THIRD REICH, AND THE GERMAN QUESTION IN THE UNITED STATES, 1933-1999 DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of the Ohio State University By Brian Craig Etheridge, M.A. The Ohio State University 2002 Dissertation Committee: Approved by Dean Michael J. Hogan, Adviser Professor Peter Hahn / Adviser Professor Alan Beyerchen History Grad Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. -

The Road Ahead Lessons in Nation Building from Japan, Germany, and Afghanistan for Postwar Iraq

The Road Ahead Lessons in Nation Building from Japan, Germany, and Afghanistan for Postwar Iraq Ray Salvatore Jennings United States Institute of Peace Peaceworks No. 49. First published April 2003. The views expressed in this report are those of the author alone. They do not necessarily reflect views of the United States Institute of Peace. UNITED STATES INSTITUTE OF PEACE 1200 17th Street NW, Suite 200 Washington, DC 20036-3011 Phone: 202-457-1700 Fax: 202-429-6063 E-mail: [email protected] Web: www.usip.org Contents Summary 5 1. Introduction 9 2. The Costs of Failing to Win the Peace in Postwar Iraq 11 3. Totalitarian Liberals, Top-Down Revolution, and a Work in Progress 13 ◗ The Occupation of Germany 13 ◗ The Occupation of Japan 15 ◗ The Ongoing Engagement in Afghanistan 19 4. The Road Here: Observations and Lessons from Germany, Japan, and Afghanistan 25 5. The Road Ahead in Iraq: Nation Building and Postwar Peace 31 Notes 36 About the Author 39 About the Institute 41 Summary ith the war in Iraq has come the responsibility to win the peace. In mili- tary campaigns, enormous resources may be marshaled at a moment’s Wnotice, including professionally trained soldiers supported by the latest technology and an intricate and elaborate global infrastructure specifically designed to fight and win wars. There is no analogous infrastructure or clarity of mission for con- tending with the aftermath of war. Indeed, the U.S. approach to postconflict recon- struction abroad is low-tech, inconsistent, improvised, and too often undone by a preoccupation with domestic politics and an instinctual aversion to nation building.