SMA CENTCOM Reach-Back Reports

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Offensive Against the Syrian City of Manbij May Be the Beginning of a Campaign to Liberate the Area Near the Syrian-Turkish Border from ISIS

June 23, 2016 Offensive against the Syrian City of Manbij May Be the Beginning of a Campaign to Liberate the Area near the Syrian-Turkish Border from ISIS Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) fighters at the western entrance to the city of Manbij (Fars, June 18, 2016). Overview 1. On May 31, 2016, the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF), a Kurdish-dominated military alliance supported by the United States, initiated a campaign to liberate the northern Syrian city of Manbij from ISIS. Manbij lies west of the Euphrates, about 35 kilometers (about 22 miles) south of the Syrian-Turkish border. In the three weeks since the offensive began, the SDF forces, which number several thousand, captured the rural regions around Manbij, encircled the city and invaded it. According to reports, on June 19, 2016, an SDF force entered Manbij and occupied one of the key squares at the western entrance to the city. 2. The declared objective of the ground offensive is to occupy Manbij. However, the objective of the entire campaign may be to liberate the cities of Manbij, Jarabulus, Al-Bab and Al-Rai, which lie to the west of the Euphrates and are ISIS strongholds near the Turkish border. For ISIS, the loss of the area is liable to be a severe blow to its logistic links between the outside world and the centers of its control in eastern Syria (Al-Raqqah), Iraq (Mosul). Moreover, the loss of the region will further 112-16 112-16 2 2 weaken ISIS's standing in northern Syria and strengthen the military-political position and image of the Kurdish forces leading the anti-ISIS ground offensive. -

Assyrians Under Kurdish Rule: The

Assyrians Under Kurdish Rule e Situation in Northeastern Syria Assyrians Under Kurdish Rule The Situation in Northeastern Syria Silvia Ulloa Assyrian Confederation of Europe January 2017 www.assyrianconfederation.com [email protected] The Assyrian Confederation of Europe (ACE) represents the Assyrian European community and is made up of Assyrian national federations in European countries. The objective of ACE is to promote Assyrian culture and interests in Europe and to be a voice for deprived Assyrians in historical Assyria. The organization has its headquarters in Brussels, Belgium. Cover photo: Press TV Contents Introduction 4 Double Burdens 6 Threats to Property and Private Ownership 7 Occupation of facilities Kurdification attempts with school system reform Forced payments for reconstruction of Turkish cities Intimidation and Violent Reprisals for Self-Determination 9 Assassination of David Jendo Wusta gunfight Arrest of Assyrian Priest Kidnapping of GPF Fighters Attacks against Assyrians Violent Incidents 11 Bombings Provocations Amuda case ‘Divide and Rule’ Strategy: Parallel Organizations 13 Sources 16 4 Introduction Syria’s disintegration as a result of the Syrian rights organizations. Among them is Amnesty Civil War created the conditions for the rise of International, whose October 2015 publica- Kurdish autonomy in northern Syria, specifi- tion outlines destructive campaigns against the cally in the governorates of Al-Hasakah and Arab population living in the region. Aleppo. This region, known by Kurds as ‘Ro- Assyrians have experienced similar abuses. java’ (‘West’, in West Kurdistan), came under This ethnic group resides mainly in Al-Ha- the control of the Kurdish socialist Democratic sakah governorate (‘Jazire‘ canton under the Union Party (abbreviated PYD) in 2012, after PYD, known by Assyrians as Gozarto). -

Nineveh 2006-1-2

NINEVEH NPublicationIN of the EAssyrian FoundationVE of AmericaH Established 1964 Volume 29, Numbers 1-2 ; First-Second Quarters ܀ 2006 ܐ ، ܐ 29 ، ܕܘܒܐ Nineveh, Volume 29, Number 1 1 ͻـͯـͼـ͕ͣ NINEVEH First-Second Quarters 2006 In this issue: :ƣNjƾNjLJ ƤܗƢƦ Volume 29, Numbers 1-2 English Section Editor: Robert Karoukian Dr. Donny George on the Assyrian National Editorial Staff: Firas Jatou name and denominational differences……..………….3 Dr. Joel Elias Assyrian Tamuz Games ‘06 ………………………….6 Tobia Giwargis Assyrian Author Testifies Before US House Sargon Shabbas, Circulation Committee on Condition of Iraq Assyrians ………….7 The Assyrian Heritage DNA Project …….…………..8 Assyrian Participation at UN Forum ………………..14 The Assyrian Flag and its Designer ………..……….16 The Rape of history, The War on Civilization……...18 POLICY 41st Anniversary of the Assyrian Foundation of America, San Francisco, CA …………………….19 Articles submitted for publication will be selected by New Publications …………………………………...24 the editorial staff on the basis of their relative merit to Malphono Gabriel Afram …………………………..26 Assyrian literature, history, and current events. Assyrian- Dutch Politician Visits Assyrians in northern Iraq …………………………..28 Opinions expressed in NINEVEH are those of the re- Film Review, The Last Assyrians …………………..29 spective authors and not necessarily those of NINE- Genocide 1915, Hypocrisy as a cornerstone VEH or the Assyrian Foundation of America. Of the Kurdish Narrative ……………………………30 On the Path of Reconciliation, U. of Istanbul ………33 Assyrian Foundation of America established in June Subscriptions & Donations …………………………36 1964 and incorporated in the state of California as a In Memoriam………………………………………..38 non-profit, tax-exempt organization dedicated to the Assyrians in Moscow Pretest Arrest ……………….40 advancement of the education of Assyrians. -

Identification of the Non-Professional Territorial Armed Formations on the MENA Region

Securitologia No 1/2016 Maciej Paszyn National Defence University, Warsaw, Poland Identification of the non-professional territorial armed formations on the MENA Region Abstract Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region is characterized by a high incidence of local intrastate or international armed conflicts. In the vast majority of cases, in these operations are involved the non-professional territorial armed forces. These are military organizations composed of volunteers living various local communities. This article shows the role and significance of these formations on the example of the civil war in Syria. Keywords: armed conflict, MENA region, territorial defence, Syrian Civil War, Free Syrian Army, Peoples Protection Units DOI: 10.5604/01.3001.0009.3835 ISSN: 1898-4509 ISSN: 2449-7436 online pdf E-mail contact to the Author: [email protected] 121 Maciej Paszyn Introduction Starting from the beginning of the mass anti-government protests called “The Arab Spring”1, 17 December 2010, in the Middle East and North Africa hereinafter referred to as the MENA, observed a significant number of armed conflicts. General character- istics of the listed conflicts defines them in the vast majority, as Non-international, anti- government military operations characterized in certain cases, as the substrate religious and activities of the international organization of Sunni-called “Islamic state” (IS)2. Described conflicts have been observed in areas such countries as Iraq, Yemen, Leb- anon, Libya and Syria. It should be noted that these are unfinished conflicts with highly dynamic events, which making it difficult to conduct research and will outdated infor- mation in certain cases. -

Cambridge University Press 978-1-108-42530-8 — Under Caesar's Sword Edited by Daniel Philpott , Timothy Samuel Shah Index More Information

Cambridge University Press 978-1-108-42530-8 — Under Caesar's Sword Edited by Daniel Philpott , Timothy Samuel Shah Index More Information Index al-Abadi, Haider, 39 African Union Mission in Somalia Abdelati, Rabie, 97 (AMISOM), 75 Abdollahi, Rasoul, 137 Ahmadinejad, Mahmoud, 136 Abducted in Iraq: A Priest in Baghdad, Ahmadis, 378, 382 37 aid neutrality, 474, 482 Abdullah (king of Saudi Arabia), 159 Aid to the Church in Need, 463, 465, 487 Abdullah, Abdul Aziz bin, 148 Aikman, David, 347, 352 Abdullah II (king of Jordan), 47 Akinola, Peter, 20 Abedini, Saeed, 140 Al-Azhar, 58 academic dialogue in Pakistan, 251 Alderstein, Yitzchok, 130 accommodation strategies Aleksei (patriarch of Moscow), 196 in China, 348, 354 Alencherry, George, 275 in Sri Lanka, 285 Aleppo, Syria, 40, 45 of Western Christians, 445 Ali, Suryadharma, 382, 384 ACCORD, 444 Alito, Samuel, 441 ACT Alliance, 465, 473 All India Catholic Union (AICU), 270 Ad Scapulam (Tertullian), 18 All India Christian Council (AICC), 270 Adaktusson, Lars, 466, 487 All Pakistan Minorities Alliance (APMA), 2, ADRA (Adventist Development and Relief 254 Agency), 185 Allen, John, 396, 421 Advisory Council of Heads of Protestant Allende, Salvador, 403 Churches of Russia, 225 Alliance Defending Freedom, 443 advocacy Alliance Defending Freedom International religious freedom advocacy by Christian (ADF), 273 TANs, 483 alliance with authoritarians, 60 in Vietnam and Laos, 324, 330 All-Union Council of Evangelical Christian- Afghanistan Baptists, 209 blasphemy, 242 Al-Monitor’s The Pulse of the Middle -

2018 Human Rights Report

2018 Human Rights Report Struggling to Breathe: the Systematic Repression of Assyrians ABOUT ASSYRIANS An estimated 3.5 million people globally comprise a distinct, indigenous ethnic group. Tracing their heritage to ancient Assyria, Assyrians speak an ancient language called Assyrian (sometimes referred to as Syriac, Aramaic, or Neo-Aramaic). The contiguous territory that forms the traditional Assyrian homeland includes parts of southern and south-eastern Turkey, north-western Iran, northern Iraq, and north-eastern Syria. This land has been known as Assyria for at least four thousand years. The Assyrian population in Iraq, estimated at approximately 200,000, constitutes the largest remaining concentration of the ethnic group in the Middle East. The majority of these reside in their ancestral homelands in the Nineveh Plain and within the so- called Kurdish Region of Iraq. Assyrians are predominantly Christian. Some ethnic Assyrians self-identify as Chaldeans or Syriacs, depending on church denomination. Assyrians have founded five Eastern Churches at different points during their long history: the Ancient Church of the East, the Assyrian Church of the East, the Chaldean Catholic Church, the Syriac Catholic Church, and the Syriac Orthodox Church. Many of these churches, as well as their various denominations, have a Patriarch at their head; this role functions, to various degrees, in a similar way to the role of the Pope in Roman Catholicism. There are at least seven different Patriarchs who represent religious Assyrian communities – however, these individuals frequently experience oppression from governmental institutions in their native countries, and consequentially often face pressure that prevents them from disclosing accurate information on the subject of human rights. -

Language Shift Among the Assyrians of Jordan: a Sociolinguistic Study

Journal of Language, Linguistics and Literature Vol. 1, No. 4, 2015, pp. 101-111 http://www.aiscience.org/journal/j3l Language Shift Among the Assyrians of Jordan: A Sociolinguistic Study Bader S. Dweik 1, *, Tareq J. Al-Refa'i 2 1Department of English, Faculty of Arts and Sciences, Middle East University, Amman, Jordan 2Department of English, Scientific College of Design, Muscat, Oman Abstract This study aimed to investigate the sociolinguistic background of the Assyrians of Jordan. It also attempted to explore the domains of use of Syriac and Arabic. In order to achieve the objectives of the study, a purposive sample of 56 respondents, covering different age ranges, genders and educational backgrounds, was chosen to respond to the linguistic questionnaire. The instruments of the study were; an open-ended interviews and a sociolinguistic questionnaire. The overall analysis of the questionnaire and the interviews indicated that the Assyrians of Jordan were witnessing a shift from their ethnic language "Syriac" towards the majority language "Arabic". They consciously placed more importance on Arabic which enabled them to be assimilated in the mainstream society. The assimilation was driven by variety of factors such as seeking security in the society as a result of what they have witnessed in their original regions. Furthermore, the Assyrians of Jordan used Arabic in almost all domains. However results proved that Syriac was still minimally used in certain key domains such as at home with family members and at church. This shift was the result of historical, economic, demographic, linguistic and generational distance. Keywords Language Shift, Assyrians, Jordan, Syriac, Arabic, Sociolinguistics Received: April 12, 2015 / Accepted: April 19, 2015 / Published online: June 8, 2015 @ 2015 The Authors. -

Uncertain Refuge, Dangerous Return: Iraq's Uprooted Minorities

report Uncertain Refuge, Dangerous Return: Iraq’s Uprooted Minorities by Chris Chapman and Preti Taneja Three Mandaean men, in their late teens and early twenties, await their first baptism, an important and recurring rite in the Mandaean religion. The baptism took place in a stream on the edge of Lund, in southern Sweden. Andrew Tonn. Acknowledgements Preti Taneja is Commissioning Editor at MRG and the Minority Rights Group International gratefully acknowledges author of MRG’s 2007 report on Iraq, Assimilation, Exodus, the following organizations for their financial contribution Eradication: Iraq’s Minority Communities since 2003. She towards the realization of this report: United Nations High also works as a journalist, editor and filmmaker specialising Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), The Ericson Trust, in human rights and development issues. Matrix Causes Fund, The Reuben Foundation Minority Rights Group International The authors would like to thank the following people: Abeer Minority Rights Group International (MRG) is a non- Dagestani, Salam Ghareb, Samira Hardo-Gharib, Kasem governmental organization (NGO) working to secure the Habib, Termida Salam Katia, Nuri Kino, Father Khalil, rights of ethnic, religious and linguistic minorities and Heatham Safo, Kate Washington, all those who contributed indigenous peoples worldwide, and to promote cooperation their time, skills and insights and all those who shared their and understanding between communities. Our activities are experiences with us during the research for this report. focused on international advocacy, training, publishing and Report Editor: Carl Soderbergh. Production Coordinator: outreach. We are guided by the needs expressed by our Kristen Harrision. Copy Editor: Sophie Mayer. worldwide partner network of organizations, which represent minority and indigenous peoples. -

Iraq's Stolen Election

Iraq’s Stolen Election: How Assyrian Representation Became Assyrian Repression ABOUT ASSYRIANS An estimated 1.5 million people globally comprise a distinct, indigenous ethnic group. Tracing their heritage to ancient Assyria, Assyrians speak an ancient language referred to as Assyrian, Syriac, Aramaic, or Neo-Aramaic. The contiguous territory that forms the traditional Assyrian homeland includes parts of southern and south- eastern Turkey, northwestern Iran, northern Iraq, and northeastern Syria. The Assyrian population in Iraq, estimated at approximately 200,000, constitutes the largest remaining concentration of the ethnic group in the Middle East. The majority of these reside in their ancestral homelands in the Nineveh Plain and within the Kurdistan Region of Iraq. Assyrians are predominantly Christian. Some ethnic Assyrians self-identify as Chaldeans or Syriacs, depending on church denomination. Assyrians have founded five Eastern Churches at different points during their long history: the Ancient Church of the East, the Assyrian Church of the East, the Chaldean Catholic Church, the Syriac Catholic Church, and the Syriac Orthodox Church. The majority of Assyrians who remain in Iraq today belong to the Chaldean and Syriac churches. Assyrians represent one of the most consistently persecuted communities in Iraq and the wider Middle East. ABOUT THE ASSYRIAN POLICY INSTITUTE Founded in May 2018, the Assyrian Policy Institute works to support Assyrians as they struggle to maintain their rights to the lands they have inhabited for thousands of years, their ancient language, equal opportunities in education and employment, and to full participation in public life. www.assyrianpolicy.org For questions and media inquiries, @assyrianpolicy contact us via email at [email protected]. -

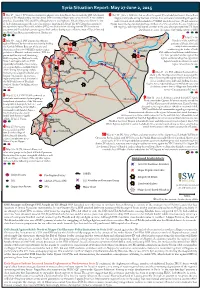

SYR SITREP Map May 27-June 2 2015

Syria Situation Report: May 27-June 2, 2015 1 May 27 – June 1: YPG forces continued to advance west from Ras al-Ayn towards the ISIS-held border 6 May 29 – June 2: ISIS launched an oensive against JN and rebel positions in the northern crossing of Tel Abyad, seizing over two dozen ISIS-controlled villages with support from U.S.-led coalition Aleppo countryside, seizing the town of Soran Azaz and several surrounding villages in a airstrikes. Meanwhile, YPG and FSA-aliated rebels in the Euphrates Volcano Operations Room in Ayn multi-pronged attack which included an SVBIED attack. In response, JN and numerous al-Arab canton announced the start of an oensive targeting Tel Abyad. e YPG denied accusations by Aleppo-based rebel groups deployed large numbers of reinforcements to the area. Clashes are the opposition Syrian National Coalition (SNC) and local activists claiming that the YPG conducted still ongoing amidst reported regime airstrikes in the area, which prompted the U.S. State executions and forced displacements against Arab civilians during recent oensives west of Ras al-Ayn and Department to accuse the regime of providing support to ISIS. on Abdul Aziz Mountain southwest of Hasaka city. Qamishli 7 May 27 – 30: 2 May 30 – June 2: ISIS launched an oensive Ayn al-Arab Residents of the rebel-held Ras al-Ayn against Hasaka City from three axes, heavily shelling 6 portions of Dera’a City held the Kawkab Military Base east of the city and 1 multiple demonstrations detonating at least two SVBIEDs against regime 10 Hasakah condemning the leaders of both FSA-aliated and Islamist rebel factions positions in Hasaka’s southern outskirts. -

The Rojava Revolution

The Rojava Revolution By Aram Shabanian Over five years ago an uprising in Dara’a, Southern Syria, set into motion the events that would eventually culminate in the multifront Syrian Civil War we see today. Throughout the conflict one group in particular has stuck to its principles of selfdefense, gender equality, democratic leadership and environmental protectionism. This group, the Kurds of Northern Syria (Henceforth Rojava), have taken advantage of the chaos in their country to push for more autonomy and, just perhaps, an independent state. The purpose of this paper is to convince the reader that increased support of the Kurdish People’s Protection Units (YPG) would be beneficial to regional and international goals and thus should be initiated immediately. Throughout this paper there will be sources linking to YouTube videos; use this to “watch” the Rojava Revolution from beginning to end for yourself. In the midst of the horror that is the Syrian Civil War there is a single shining glimmer of hope; Rojava, currently engaged in a war for survival and independence whilst simultaneously engaging in a political experiment the likes of which has never been seen before. The Kurds are the secondlargest ethnic group in the middle east today, spanning four countries (Iraq, Iran, Syria and Turkey) but lacking a home state of their own. Sometimes called the ultimate losers in the SykesPicot agreement, the Kurds have fought for a homeland of their own ever since said agreement was signed in 1916. The Kurds in all of the aforementioned nations are engaged in some degree of insurrection or another. -

Eagles Riding the Storm of War: the Role of the Syrian Social Nationalist Party

JANUARY 2019 Eagles riding the storm of war: CRU Policy Brief The role of the Syrian Social Nationalist Party Among the myriad of loyalist militias that have augmented Assad’s battlefield prowess, the Eagles of Whirlwind of the Syrian Social Nationalist Party (SSNP) stand out as an exemplary pro-regime hybrid coercive organization that filled an enormous manpower gap and helped turn the tide of war. The regime permitted the Eagles to defend and police Syrian territory and in some cases fight alongside the Syrian Arab Army on the frontlines. In its role as paramilitary auxiliary, the group proved to be a capable and effective force. In parallel, the parent political party of the Eagles, the Syrian Social Nationalist Party has sought to leverage the battlefield successes and prestige of its fighters into political gains. Historically a political rival to the Syrian Ba’ath party, the SSNP has been able to translate the achievements of the Eagles into ministerial positions and open recruitment drives across regime-held territory. However, the success of the Eagles has not led to a larger or more permanent role for the armed group. Demonstrating the complexity of hybrid security actors in the Levant, the SSNP offered the Assad regime a novel form of support that traded greater political auton- omy in exchange for paramilitary mobilization in support of the regime. For the Assad regime, accepting the price of greater autonomy for the SSNP was a calculated deci- Chris Solomon, Jesse McDonald & Nick Grinstead sion outweighed by the add-on auxiliary fighting capacity of the Eagles of Whirlwind.