Voiceworks New fiction, Nonfiction, Poetry, Comics & Visual Art from Young Australians

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Halal Snack Pack", Also Known As an "HSP" in G) Australia's Islamic Council Wasn't Happy About Australia

BreakingNewsEnglish - The Mini Lesson Halal snack helps bring True / False Australians together a) A halal snack was Australia's Word of the Year for 2016. T / F 8th April, 2017 b) The snack was created in the Middle East in A new kind of fast 2015. T / F food is having a big c) The halal snack is now a symbol of impact in Australia. It multiculturalism. T / F has helped to bring Australian people d) The halal snack Facebook page has more than together, and it has 1800,000 members. T / F been named as the e) A politician from the far right refused to eat People's Choice Word the halal snack. T / F of the Year 2016 by Australia's Macquarie f) The politician's words and actions made the Dictionary. It is the halal snack less popular. T / F "halal snack pack", also known as an "HSP" in g) Australia's Islamic Council wasn't happy about Australia. It is a combination of kebab meat, potato the Word of the Year. T / F fries and a special spicy sauce. Although the snack was created in Australia, it has its roots in the h) The Islamic Council suggested everything is Middle East. It has become a symbol of good and positive. T / F multiculturalism in Australia as more people become aware of halal food. There is even an HSP Synonym Match group on Facebook that has over 180,000 (The words in bold are from the news article.) members. The site is for, "sharing great snack pack stories and discussing possibly the best snack pack 1. -

On Tour 2018 Product Catalogue Sweets | 2 Welcome

On Tour 2018 Product Catalogue Sweets | 2 Welcome Dear Customer, We constantly strive to adapt our product range to the needs of the market, as we hope you have already experi- enced. Customer satisfaction is our highest priority, which we aim to achieve through perfect service, innovation and sustainability. To help you find the products you are looking for, whether that is a complimentary snack for your passengers or a buy-on-board product, we have created this catalogue. We aim to give you an overview of the trends and possi- bilities that are currently available in the market. We have concentrated on the core product categories and have in- cluded a selection of our product range, but LSG Group is able to fulfill almost any wish you have, as we have done in the past. Together with you, we at LSG Group would like to create an even more diversified offering in order to better and more efficiently meet the needs of your passengers. By creating this catalogue, we hope we have helped you in your decision making process and are looking forward to intensifying our business relationship in the future. Content Sweets Page 7-41 Content | 4 Salty Page 42-45 Bread/Cakes/Hot Snacks Page 46-52 Dairy Page 53-55 Frozen Page 56-57 Dry Goods/Specialities Page 58-64 Drinks Page 65-77 Content | 5 How to use? As a specialist in the area of onboard service LSG We are confident that our offerings will facilitate your Group can offer an exceptional variety of products in numerous cat- sourcing activities by providing a great variety of products from a egories. -

Report AFTER a TURBULENT FEW YEARS, PG

UMAMI: THE THE CANADIAN UNLOCKING 25 FIFTH TASTE 26 HALAL CONSUMER 39 SUSTAINABLE GROWTH Inside ACCENT ALIMENTAIRE SUR LE QUÉBEC PG.41 GOING WHOLE HOG THE NOSE-TO-TAIL MOVEMENT PG.30 The 2015 PwC ROUNDTABLE MEAT report AFTER A TURBULENT FEW YEARS, PG. 33 THE MEAT AND POULTRY SECTOR IS POISED TO CAPTURE NEW GROWTH OPPORTUNITIES PG.22 MARCH 2015 | $15.00 | FoodInCanada.com PM #40069240 001-2_Coverv1.indd 1 15-03-05 10:27 AM A TRUSTED SUPPLIER FOR MORE T H A N 3 0 YEARS. BETTER SCIENCE. See for yourself: BETTER RESULTS . n Increase yields n Reduce sodium content n Achieve consistent results n Improve product quality n Enhance natural product flavors n Extend product shelf-life n Inhibit pathogen outgrowth 2015 1.800.827.1727|www.wtiinc.com 001-2_Coverv1.indd 2 15-02-25 12:16 PM XtremeBICAd_Layout 1 2/10/15 4:39 PM Page 1 VOLUME 75, NUMBER 2 • MARCH 2015 Best-in-Class Performance PUBLISHER | Jack Meli (647) 823-2300 [email protected] EDITOR | Carolyn Cooper (416) 442-5600 x3232 [email protected] MANAGING EDITOR | Deanna Rosolen (416) 442-5600 x3234 [email protected] ART DIRECTOR | Melissa Crook (416) 442-5600 x3260 [email protected] Combine the Xtreme’s benchmark-setting sensitivities with its feature packed controls in a high-pressure wash ACCOUNT MANAGER | Daniela Piccone down design... all at the price of a mid-range detector, (416) 510-6773 and you’ve got the best dollar-for-dollar value on the [email protected] market today. PRODUCTION MANAGER | Steve Hofmann Download (416) 510-6757 Brochures [email protected] & Market Guides CIRCULATION MANAGER | Cindi Holder Visit Purity.Eriez.com Call 888-300-3743 (416) 442-5600 x3544 [email protected] Editorial Advisory Board: Carol Culhane, president, International Food Focus Ltd.; Gary Fread, president, Fread & Associates Ltd.; Linda Haynes, co-founder, ACE Bakery; Dennis Hicks, president, Pembertons; Larry Martin, Dr. -

BREAKFAST Evening Dining ENTREES Looking for Lunch?

SNACK PACK FOR 4 | $119 BREAKFAST Evening dining 32 chicken wings, 14 chicken fingers, 1 pizza your choice, bowl of Caesar, French fries. Carrot and celery sticks, ranch dip, choice of sauce on the sauce: Available Saturday & Sunday 7:30 am to 11:00 am Available 5:00 pm to 10:00 pm mild BBQ, medium, house Hot!, honey garlic or Deerhurst signature maple bacon sauce Continental Breakfast for 2 | $32 or 4 | $48 SNACKS & SUCH Fresh fruit salad, individual yogurts, Deerhurst house granola, muffins, bagels, cream cheese, butter, margarine, preserves. PIZZAS (12”) Hummus Dip and Crackers | $12 Gluten free crust - add $3 for 12” Substitute gluten free bread $1 French Fries | $8.50 Add side of gravy | $1.50 Try our Family Friendly Pizza & Salad Combo for 4 | $51 Family Breakfast for 4 | $56 Scrambled eggs, bowl of fresh fruit, 12 breakfast link sausage, Classic Poutine | $12.50 Fries, cheese curds, gravy Bowl of house or Caesar salad plus choice of two 12” pizzas home fries and shredded cheddar. Choice of toasted white, brown, multigrain or rye. Vegetarian Poutine| $15 Four Cheese | $18 1 liter of orange juice Tomatoes, onions, peppers, green onions, cheese curds, vegan gravy Herbed tomato sauce, mozzarella, cheddar, parmesan, feta cheese Margarine or butter on the side with preserves Substitute gluten free bread $1 Chicken Wings | 7 pcs $11.50 | 14 pcs $ 19 | 48 pcs $56 The Classic | $20 Halal Certified / Gluten free wings Herbed tomato sauce, mozzarella and cheddar cheese, pepperoni Fresh Fruit Cup | $8.50 Carrot and celery sticks, ranch dip and choice of sauce on the sauce: Mild BBQ, Medium, House Hot!, Honey Garlic or Deerhurst Signature Maple Bacon sauce Veggie Delight | $20 Yogurt, Fresh Fruit, Granola Parfait | $9.50 Garden pesto sauce, peppers, tomato, onions, mushroom, Charcuterie Board for Two | $28 feta cheese, balsamic drizzle Breakfast Muffins of the Day / 6 pack | $11.50 Cured meats, Quebec and Ontario cheese, marinated vegetables, Butter, fruit preserves. -

853-2011 Inventory Price List

Date: 01/22/10 WILL POULTRY Page: 1 Time: 12:15 PM 1075 WILLIAM STREET BUFFALO, NY 14240-1146 Phone: (716) 853-2000 - Fax: (716) 853-2011 Inventory Price List - Effective 01/22/10 Class: KOSHER,PASSOVER KOSHER PRODUCT CATALOG Item Brand Pack Description Name Size Class Name: KOSHER CHIX LIVERS 50#cw KOSHER AARONA 50#w TURKEYS 12-14 FRESH AGRI 2/12# cw AARONS 2/12# cw ROAST BEEF COOKED AARONS AARONS 2/5#CW TURKEY BRST MEX STYLE RETAIL AARONS 9#cw WINGS WHOLE KOSHER 50#CW AARONS 50#CW TURKEY 10/12 4/CS KOSHER AARONS 46#CW TURKEY BREAST 8/10# RUBASHKIN AARONS 4/9#CW SALAMI SLICED SHOR HABOR AARONS 6# TURKEY VARIETY PACK AARONS 12# BEEF FRY SLICED 12/6oz AARONS 12/6oz CORNED BEEF SLICED 12/6oz PKGS AARONS 12/6 OZ T/P CHIX FRYER ORGANIC AARONS 40#cw T/P CHIX BRST CUTLET FAM PK 12/2# AARONS 12/2# T/P GROUND BEEF 1160 AARONS 12/1.5#CW TURKEY BREAST SMOKED KOSHER AARONS 15#CW BOLOGNA 2/6#CW AARONS AARONS 2/6#CW FRANKS 16OZ AARONS AARONS 12#CW SALAMI BEEF STRING TIED AARONS 12#cw POLISH SAUSAGE AGRI AARONS 12/1# FRANKS CHIX 12/1 # AARON'S AARONS 12/1# SALAMI 5# HARD/THIN AARON'S AARONS 3/5#CW FRANKS 16/12oz AGRI AARONS 16/12oz T/P LONDON BROIL RST. 1130 AARONS BEST 6/1.5#CW T/P CHUCK EYE ROAST #3764 AARONS BEST 5-3/4#CW T/P CHUCK STEAK BNLS 1170 AARONS BEST 6/1.25#CW T/P RIBEYE STEAK 1173 AARONS BEST 12/1.25#CW T/P RIB STEAK B/ I 12 0Z 1176 1175 AARONS BEST 6/12OZ.#CW HERRING CHOPPED SALAD 5# ACME 5# KIPPERED SALMON ACME 2#CW SALMON SALAD 5LB ACME ACME 5# SABLE PLATE PIECE ACME ACME 2.5#CW WHITEFISH SALAD 5# ACME ACME 5# NOVA SIDE SALMON ACME 6#CW -

Lesson Day 71 – Day 75

DAY 71 Sales quotas exploit convenience store workers part-timers are not exploited. One part-time worker said he was "drowning in quotas". Another said that workers can lose up to 20-30% of their Convenience stores provide many monthly salary. The biggest losses come with quotas for unsold seasonal of us with a handy place to pop into items like Valentines and Christmas goods and special sushi rolls. 24 hours a day to buy things we have forgotten or didn't have time WORD CHECK UP to get from other stores. They also 1. Breach /britʃ/ provide part-time jobs for thousands of people. A new report 2. Merchandise /ˈmɜr·tʃənˌdɑɪs/ from Japan suggests that some convenience stores are not so convenient for 3. Specialist /ˈspeʃ·ə·lɪst/ its workers. The report, from Japan's national broadcaster NHK, says overbearing and unrealistic sales quotas are being imposed on many part- TRUE / FALSE: Read the headline. Guess if a-h below are true (T) or false time workers. Labor rights experts are calling on store bosses to stop what (F). they deem to be an exploitative practice. There are reports of workers The article said convenience stores were dandy places to pop into. T / F having hundreds of dollars deducted from their salaries and having to buy unsold stock for failing to meet the quotas. The article has news about a report from Japan's national broadcaster. T / F A report said sales quotas given to part-timers were unrealistic. T / F The report says workers have salaries deducted for not meeting quotas. -

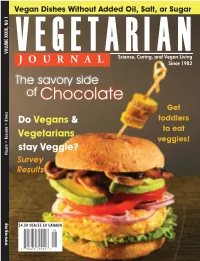

VJ Issue1 2014.Pdf

Vegan Dishes Without Added Oil, Salt, or Sugar VOLUME XXXIII, NO 1 XXXIII, VOLUME Science, Caring, and Vegan Living VEGETAJ OURNAL R IANSince 1982 The savory side of Chocolate Get ics H t e Do Vegans & toddlers • to eat cology Vegetarians e veggies! • H ealt stay Veggie? H Survey Results $4.50 USA/$5.50 CANADA www.vrg.org MANAGING EDITOR: Debra Wasserman FEATURES utrition otline SENIOR EDITOR: Samantha Gendler N H EDITORS: Carole Hamlin, Jane Michalek, Charles Stahler 6 · Beyond Meat Veggie Chicken Strips NUTRITION EDITOR: Reed Mangels, PhD, RD Jeanne Yacoubou, MS, highlights this Maryland company. QUESTION: What are some ways to Toddlers often don’t care for NUTRITIONAL ANALYSES: Suzanne Hengen REED MANGELS, PhD, RD get toddlers to eat vegetables? the bitter taste of some vegetables. COVER PHOTOGRAPHY: Linda Long 7 · Kendal at Oberlin COVER FOOD STYLING: Jill Keller J.C., via email. Choosing sweeter vegetables such VRG VOLUNTEER COORDINATOR A retirement community offering vegetarian/vegan options. as carrots, corn, peas, and sweet AND CATALOG MANAGER: Soren Clarkwest ANSWER: It is important to try to potatoes can lead to success. For WEB DEVELOPMENT: Alan Polster 10 · The Savory Side of Chocolate RESEARCH DIRECTOR: Jeanne Yacoubou find ways to get toddlers to eat other vegetables, one way to Debra Daniels-Zeller gets creative with cocoa. vegetables. Children who eat few reduce the bitterness is to serve RESTAURANT GUIDE/MEMBERSHIP: Sonja Helman VEGETARIAN RESOURCE GROUP ADVISORS: vegetables tend to also eat a lim- them raw or lightly steamed rather Arnold Alper, MD; Nancy Berkoff, EdD, RD; 16 · Vegan Dishes without Added Oil, ited variety of vegetables as adults1. -

![Copy of Mini SEO Audit [SAMPLE]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5843/copy-of-mini-seo-audit-sample-7895843.webp)

Copy of Mini SEO Audit [SAMPLE]

Mini SEO Audit Target site: https://deepindiankitchen.com Overview Date: Sep , 2020 This audit has been put together to help you make sense of how your website is performing. We pull together data from Google Search Console, Ahrefs, Screaming Frog and more to get a birds-eye view of SEO performance. Navigation: Summary: ▶ On-Page SEO Audit Findings Post-Launch Position Change ▶ Keyword Research # Of KWs # Of KWs # Of KWs ▶ SEO Installation ▶ URL Equity #1-5 22 0 -22 ▶ Redirect Chains ▶ Redirect Mapping #6-10 12 0 -12 ▶ Competitor Comparison #11+ 1097 0 -1097 TOTALS 1131 0 -1131 SEO / On-Site Part of Installation Process? Keyword Usage/Targeting We will pick the best keywords for each of your highest priority pages. We Pages aren't necessarily targeting the highest value/desired keywords provided. will use these when rewriting title tags C Keyword selection can be improved and worked into titles, meta descs and content. & meta descriptions. Title Tags We will rewrite title tags for your highest priority pages and install them Title tags are not unique and some only have the brand name. They should be on the website. D rewritten to include primary keywords. Meta Descriptions We will rewrite unique meta descriptions for your highest priority A lot of autogenerated meta descriptions. These should be rewritten to target pages and install them on the website. D pirmary and secondary keywords. Redirects We will provide a list of redirects for your web developers to implement. In No issues with redirects. some cases we are able to fix these on A our own. -

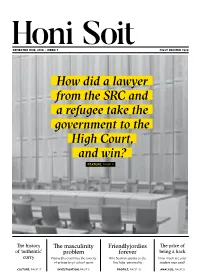

How Did a Lawyer from the SRC and a Refugee Take the Government to the High Court, and Win? FEATURE, PAGE 11

HSEMESTER ONE,oni 2016 • WEEK 7 Soit FIRST PRINTED 1929 How did a lawyer from the SRC and a refugee take the government to the High Court, and win? FEATURE, PAGE 11 The history The masculinity Friendlyjordies The price of of ‘authentic’ problem forever being a hack curry Pranay Jha examines the toxicity Riki Scanlan speaks to the How much are your of private boys’ school sport YouTube personality student reps paid? CULTURE, PAGE 17 INVESTIGATION, PAGE 6 PROFILE, PAGE 10 ANALYSIS, PAGE 9 2 HONI SOIT SEMESTER 1 • WEEK 7 HONI SOIT SEMESTER 1 • WEEK 7 3 LETTERS EDITOR-IN-CHIEF been unable to substantiate this, impulse that leads students reational activities and foster But, then, a team entirely ACKNOWLEDGEMENT Lost in but it has not been for the lack to publicise challenging and social relationships with peo- made up of women is. of course, Tom Joyner of my trying. I would like to intriguing material. But I fear ple of a similar age to the cen- cause for celebration (oh, the OF COUNTRY bureacracy know whether this is indeed the that the space is too often tre residents. It’s a shame for diversity, just how could you get EDITORS case, and if so, why these candi- dominated by a few groups. these activities to be described more sexually diverse!) Contents We acknowledge the traditional and centre the experiences of To the responsible Sydney Uni- dates were priotised over me. Although I'm sympathetic to as ‘pitiably boring time-fillers.’ Hypocrites and phoneys. Andrew Bell, Natalie Buckett, custodians of this land, the Gadi- Indigenous people, and to be versity administrator (if thou I have no faith in the radicalism, I feel that radical It’s wrong to focus on what Just admit you're a bunch of 2 / LETTERS 16 / CULTURE Max Hall, Sam Langford, Alex- gal people of the Eora Nation. -

World Meats Inc

WORLD MEATS INC. CURRENT SPECIALS: CHICKEN NUGGETS ON SALE FOR $25.00 SAVE $5.00/BOX! DICED PANCHETTA ON SALE FOR $11.00! KOLBASSA CHUBS ON SALE FOR $12.00! SURF & TURF BOXES & HOLIDAY SPECIALS STILL ON SALE! SEE OUR PRODUCT BROCHURE FOR MORE DETAILS! WORLD MEATS INC. 2255 Dunwin Drive, Mississauga, ON , L5L 1A3 Toll Free: 1-877-593-9639 | Local: 905-569-0559 | [email protected] VARIETY PACKS VARIETY PACKS RET-6058 Grill Box #1 $89.00/Box 6 pieces AAA Top Sirloin Steaks Baseball Cut 4oz, 6 pieces Chicken Breast Boneless Skinless, 6 pieces Prime Rib Burgers 6oz, 6 pieces Sweet Italian Sausages (3 pc/pkg), 3 pieces Wild Pacific Salmon Fillets 6oz (3pc/pkg), 1 lb Sliced Bacon, 1 pkg Arla Sliced Mild Cheddar Cheese (165 grm pkg - 8 slices per pkg) RET-6059 Grill Box #2 $168.00/Box 12 pieces AAA Top Sirloin Steaks Baseball Cut 4oz, 12 pieces Chicken Breast Boneless Skinless, 12 pieces Prime Rib Burgers 6oz, 12 pieces Sweet Italian Sausages (3 pc/pkg), 6 pieces Wild Pacific Salmon Fillets 6oz (3pc/pkg), 2 lb Sliced Bacon, 2 pkg Arla Sliced Mild Cheddar Cheese (165 grmpkg - 8 slices per pkg) RET-6061 Halal Grill Box #1 $99.00/Box 6 pieces AAA Top Sirloin Steaks Baseball Cut 4oz, 6 pieces Chicken Breast Boneless Skinless, 6 pieces Prime Rib Burgers 6oz, 6 pieces Sweet Italian Sausages (3 pc/pkg), 3 pieces Wild Pacific Salmon Fillets 6oz (3pc/pkg), 1 lb Sliced Bacon, 1 pkg Arla Sliced Mild Cheddar Cheese (165 grm pkg - 8 slices per pkg) RET-6062 Halal Grill Box #2 $188.00/Box 12 pieces AAA Top Sirloin Steaks Baseball Cut 4oz, 12 pieces -

USF Product List FROZEN 122910

ITEM # CATEGORY DESCRIPTION BRAND PACK/SIZE 90109 ACME FISH PRODUCTS SALMON PORTIONS KOSHER ACME 12/16 OZ 960100 ACME FISH PRODUCTS NOVA PIECES GROUND ACME 4/5 LB 960102 ACME FISH PRODUCTS VAC PACK SLICED LOX 3oz ACME 12/3oz 960107 ACME FISH PRODUCTS SLICED NOVA TRAYS ACME 6/3 LB 960406 ACME FISH PRODUCTS PRE-SLC NORWEG.SALMON ACME 12/4oz 961206 ACME FISH PRODUCTS VAC PACK NOVA ACME 12/3 oz 192415 ACME FISH SLADS MACKEREL PEPPERED ACME 1/3 CT 961997 ACME FISH SLADS SMOKED TROUT FILLET ACME 1/20LB 109922 APPETIZERS POTATO LOADED STICKS LIBERTY 6/2LB 190967 APPETIZERS ONION RINGS MOORES 8/2LB 190968 APPETIZERS ONION RING BREADED EXTR FRED'S 8/2# 190969 APPETIZERS ONION O'S BREADED PCK RICH 6/2LB 255295 APPETIZERS EGG ROLL VEGETABLES MATLAWS 50/3OZ 370678 APPETIZERS VEGETABLE SPRING ROLL CHEF ONE 1/200PC 371127 APPETIZERS RAVIOLI CHEESE BREADED McCAINS 6/3LB 409554 APPETIZERS MOZZARELLA STCK BATTERED McCAINS 6/2LB 420444 APPETIZERS CORDON BLEU MINI TYSON 8/25.5OZ 700292 APPETIZERS ZUCCHINI STICK BATTERED CAVENDISH 6/2LB 700293 APPETIZERS MUSHROOMS WHOLE BATTERED CAVENDISH 6/2LB 700294 APPETIZERS ONION RING BEER BATTERED CAVENDISH 6/2.5LB 700295 APPETIZERS POTATO SLICES BATTERED CAVENDISH 4/5LB 730230 APPETIZERS CHEESESTIX 96CT BETZBOYS 96/1.2OZ 801015 APPETIZERS ONION RINGS HOMESTLYE RAY SAOUD 6/2.5LB 801501 APPETIZERS BREADED MOZZARELLA STICK ANCHOR 4/4 LB 801601 APPETIZERS BATTERED MAC & CHSE WEDGE ANCHOR 6/3LB 801603 APPETIZERS BROC CHED BITES ANCHOR 6/2.5LB 801604 APPETIZERS #5800 BRD. ZUCCHINI STCKS ANCHOR 4/3.5 LB 801606 APPETIZERS -

Mcdonald's Canada Ingredients Listing

McDonald’s Canada Ingredients Listing As of September 27, 2021 Provided in this document is a listing of components in our popular menu items by category, followed by the ingredient statements for those components. Allergens contained within these components are indicated in capital type at the end of each respective ingredient statement (following the word “CONTAINS”). We encourage guests to check these statements regularly as ingredients in menu items may change. Important Note: At McDonald’s, we take great care to serve quality, great-tasting menu items to our guests each and every time they visit our restaurants. We understand that each of our guests has individual needs and considerations when choosing a place to eat or drink outside their home, especially those guests with food allergies. As part of our commitment to you, we provide the most current ingredient information available from our food suppliers for the ten priority food allergens identified by Health Canada (eggs, milk, mustard, peanuts, seafood [including fish, crustaceans and shellfish], sulphites, sesame, soy, tree nuts, and wheat and other cereal grains containing gluten) so that our guests with food allergies can make informed food selections. However, we also want you to know that despite taking precautions, normal kitchen operations may involve some shared storage, cooking and preparation areas, equipment, utensils and displays, and the possibility exists for your food items to come in contact with other food products, including other allergens. We encourage our guests with food allergies or special dietary needs to visit www.mcdonalds.ca for ingredient information, and consult their doctor for questions regarding their diet.