Etd-Tamu-2004B-HIST-Godin.Pdf (369.7Kb)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tasker H. Bliss and the Creation of the Modern American Army, 1853-1930

TASKER H. BLISS AND THE CREATION OF THE MODERN AMERICAN ARMY, 1853-1930 _________________________________________________________ A Dissertation Submitted to the Temple University Graduate Board __________________________________________________________ in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY __________________________________________________________ by Thomas R. English December 2014 Examining Committee Members: Richard Immerman, Advisory Chair, Temple University, Department of History Gregory J. W. Urwin, Temple University, Department of History Jay Lockenour, Temple University, Department of History Daniel W. Crofts, External Member,The College of New Jersey, Department of History, Emeritus ii © Copyright 2014 By Thomas R. English All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT A commonplace observation among historians describes one or another historical period as a time of “transition” or a particular person as a “transitional figure.” In the history of the United States Army, scholars apply those terms especially to the late- nineteenth century “Old Army.” This categorization has helped create a shelf of biographies of some of the transitional figures of the era. Leonard Wood, John J. Pershing, Robert Lee Bullard, William Harding Carter, Henry Tureman Allen, Nelson Appleton Miles and John McCallister Schofield have all been the subject of excellent scholarly works. Tasker Howard Bliss has remained among the missing in that group, in spite of the important activities that marked his career and the wealth of source materials he left behind. Bliss belongs on that list because, like the others, his career demonstrates the changing nature of the U.S. Army between 1871 and 1917. Bliss served for the most part in administrative positions in the United States and in the American overseas empire. -

Historic Structure Report: Battery Horace Hambright, Fort Pulaski National Monument, Georgia

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Fort Pulaski National Monument Georgia Battery Horace Hambright Historic Structure Report Cultural Resources, Partnerships and Science Division Battery Horace Hambright Fort Pulaski National Monument, Georgia Historic Structure Report February 2019 Prepared by: Panamerican Consultants, Inc. 2390 Clinton Street Buffalo, New York 14227 Wiss, Janney, Elstner Associates, Inc. 330 Pfingsten Road Northbrook, Illinois 60062 Prepared for: National Park Service Southeast Regional Office 100 Alabama Street SW Atlanta, Georgia 30303 Cultural Resources, Partnership and Science Division Southeast Region National Park Service 100 Alabama Street, SW Atlanta, Georgia 30303 (404) 562-3117 About the front cover: View of Battery Horace Hambright from HABS GA-2158. This manuscript has been authored by Panamerican Consultants, Inc., and Wiss, Janney, Elstner Associates, Inc., under Contract Number P16PD1918 with the National Park Service. The United States Government retains and the publisher, by accepting the article for publication, acknowledges that the United States Government retains a non-exclusive, paid-up, irrevocable, worldwide license to publish or reproduce the published form of this manuscript, or allow others to do so, for United States Government purposes. Battery Horace Hambright Fort Pulaski National Monument, Georgia Historic Structure Report Contents List of Figures .................................................................................................................................................................. -

Bostonians and Their Neighbors As Pack Rats

Bostonians and Their Neighbors as Pack Rats Downloaded from http://meridian.allenpress.com/american-archivist/article-pdf/24/2/141/2744123/aarc_24_2_t041107403161g77.pdf by guest on 27 September 2021 By L. H. BUTTERFIELD* Massachusetts Historical Society HE two-legged pack rat has been a common species in Boston and its neighborhood since the seventeenth century. Thanks Tto his activity the archival and manuscript resources concen- trated in the Boston area, if we extend it slightly north to include Salem and slightly west to include Worcester, are so rich and diverse as to be almost beyond the dreams of avarice. Not quite, of course, because Boston institutions and the super—pack rats who direct them are still eager to add to their resources of this kind, and constantly do. The admirable and long-awaited Guide to Archives and Manu- scripts in the United States, compiled by the National Historical Publications Commission and now in press, contains entries for be- tween 50 and 60 institutions holding archival and manuscript ma- terials in the Greater Boston area, with the immense complex of the Harvard University libraries in Cambridge counting only as one.1 The merest skimming of these entries indicates that all the activities of man may be studied from abundant accumulations of written records held by these institutions, some of them vast, some small, some general in their scope, others highly specialized. Among the fields in which there are distinguished holdings—one may say that specialists will neglect them only at their peril—are, first of all, American history and American literature, most of the sciences and the history of science, law and medicine, theology and church his- tory, the fine arts, finance and industry, maritime life, education, and reform. -

The Insular Cases: the Establishment of a Regime of Political Apartheid

ARTICLES THE INSULAR CASES: THE ESTABLISHMENT OF A REGIME OF POLITICAL APARTHEID BY JUAN R. TORRUELLA* What's in a name?' TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................ 284 2. SETFING THE STAGE FOR THE INSULAR CASES ........................... 287 2.1. The Historical Context ......................................................... 287 2.2. The A cademic Debate ........................................................... 291 2.3. A Change of Venue: The Political Scenario......................... 296 3. THE INSULAR CASES ARE DECIDED ............................................ 300 4. THE PROGENY OF THE INSULAR CASES ...................................... 312 4.1. The FurtherApplication of the IncorporationTheory .......... 312 4.2. The Extension of the IncorporationDoctrine: Balzac v. P orto R ico ............................................................................. 317 4.2.1. The Jones Act and the Grantingof U.S. Citizenship to Puerto Ricans ........................................... 317 4.2.2. Chief Justice Taft Enters the Scene ............................. 320 * Circuit Judge, United States Court of Appeals for the First Circuit. This article is based on remarks delivered at the University of Virginia School of Law Colloquium: American Colonialism: Citizenship, Membership, and the Insular Cases (Mar. 28, 2007) (recording available at http://www.law.virginia.edu/html/ news/2007.spr/insular.htm?type=feed). I would like to recognize the assistance of my law clerks, Kimberly Blizzard, Adam Brenneman, M6nica Folch, Tom Walsh, Kimberly Sdnchez, Anne Lee, Zaid Zaid, and James Bischoff, who provided research and editorial assistance. I would also like to recognize the editorial assistance and moral support of my wife, Judith Wirt, in this endeavor. 1 "What's in a name? That which we call a rose / By any other name would smell as sweet." WILLIAM SHAKESPEARE, ROMEO AND JULIET act 2, sc. 1 (Richard Hosley ed., Yale Univ. -

The Armored Infantry Rifle Company

POWER AT THE PENTAGON-byPENTAGON4y Jack Raymond NIGHT DROP-The American Airborne Invasion $6.50 of Normandy-by S. 1.L. A. Marshall The engrossing story of one of 'thethe greatest power Preface by Carl Sandburg $6.50 centers thethe world has ever seen-how it came into Hours before dawn on June 6, 1944, thethe American being, and thethe people who make it work. With the 82dB2d and 1101Olst st Airborne Divisions dropped inin Normandy awesome expansion of military power in,in the interests behind Utah Beach. Their mission-to establish a firm of national security during the cold war have come foothold for the invading armies. drastic changes inin the American way of life. Mr. What followed isis one of the great and veritable Raymond says, "in the process we altered some of stories of men at war. Although thethe German defenders our traditionstraditions inin thethe military, in diplomacy, in industry, were spread thin, thethe hedgerow terrain favored them;them; science, education, politics and other aspects of our and the American successes when they eventually did society." We have developed military-civilian action come were bloody,bloody.- sporadic, often accidential. Seldom programs inin he farfar corners of the globe. Basic Western before have Americans at war been so starkly and military strategy depends upon decisions made in candidly described, in both theirtheir cowardice and theirtheir America. Uncle Sam, General Maxwell Taylor has courage. said, has become a world-renowned soldier in spite In these pages thethe reader will meet thethe officers whowho of himself. later went on to become our highest miliary com-com DIPLOMAT AMONG WARRIOR5-byWARRI0R-y Robert manders in Korea and after: J. -

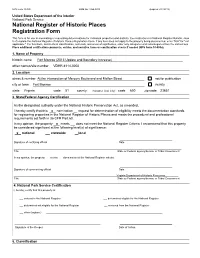

Fort Caswell Historic District Fort Caswell, West and South Walls

NORTH CAROLINA STATE HISTORIC PRESERVATION OFFICE Office of Archives and History Department of Cultural Resources NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES Fort Caswell Historic District Caswell Beach vicinity, Brunswick County, BW0230, Listed 12/31/2013 Nomination by Jennifer Martin Mitchell Photographs by Claudia Brown, January 2010, and Jennifer Martin Mitchell, July 2012 Fort Caswell, west and south walls – 1827-1838 19thth Company and 31st Company Barracks – 1901 Battery Bagley – 1898-1899 Historic District Map NPS Form 10-900 OMB No. 10024-0018 (Oct. 1990) United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for individual properties and districts. See instructions in How to Complete the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form (National Register Bulletin 16A). Complete each item by marking “x” in the appropriate box or by entering the information requested. If an item does not apply to the property being documented, enter “N/A” for “not applicable.” For functions, architectural classification, materials, and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions. Place additional entries and narrative items on continuation sheets (NPS Form 10-900a). Use a typewriter, word processor, or computer, to complete all items. 1. Name of Property historic name Fort Caswell Historic District, 31BW801** other names/site number 2. Location street & number 100 Caswell Beach Road N/A not for publication city or town Caswell Beach vicinity state North Carolina code NC county Brunswick code 019 zip code 28465 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act, as amended, I hereby certify that this nomination request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set for in 36 CFR Part 60. -

The Oxford Democrat : Vol. 49, No. 44

arma were raised at once A friend to the rich and poor. A medi- in a of trunks. She A GOOD SWORD 8TROKK. A dozen THE BABY SORCERESS. So Eolia in the old house to set black, guarding pile cine th»t strengthens and heals, Is Brown's stayed the with his looked at him for a moment ; he touched against solitary man, who, Iron Bitten·. it to rights, with the aid of Mrs. Chubb'n Mail ! UY THOMAS WRXTWORTH 1IIUGIXSON. HOW COT.. DF.MALET MET HIS MATCH. back the wall, and one foot on Goods his hat. against As a the men who ►von driven by red-armed oldest daughter, and Bessie rule, have Dry of Mr sit· beneath lt>e Uilt " the of hie horse confronted crazy misfortune did not have far to go. Kv>r the »<-coaod:t:ioa baby elin-lree, Good he said sternly by went to town to their little ston morning, miss," respect- body Λ wreath of ribbon· ia her hands; up pack tangled was & on in a them. Henri DeMalet Colonel ex- There high frolic going (now directions Γ »r every use are She twines ami twists the many colored of furniture and send it down by the fully. >»#'*Kxpllclt out of Town " i t " one fine DeMalet of the French was given with the )>i imoud dyiug Ladies Living strands.— sal Uood said Bessie. I email town of Southern France Cuirassera) Dyes, &«T* And the first night that they morning," Mosses. Grasses. ft'·. OUf A little so press. K?ïs, Ivory, Hair, f·*"» 1 ν'·* rem·**, weaving deatlnes. -

The Inventory of the Theodore Roosevelt Collection #560

The Inventory of the Theodore Roosevelt Collection #560 Howard Gotlieb Archival Research Center ROOSEVELT, THEODORE 1858-1919 Gift of Paul C. Richards, 1976-1990; 1993 Note: Items found in Richards-Roosevelt Room Case are identified as such with the notation ‘[Richards-Roosevelt Room]’. Boxes 1-12 I. Correspondence Correspondence is listed alphabetically but filed chronologically in Boxes 1-11 as noted below. Material filed in Box 12 is noted as such with the notation “(Box 12)”. Box 1 Undated materials and 1881-1893 Box 2 1894-1897 Box 3 1898-1900 Box 4 1901-1903 Box 5 1904-1905 Box 6 1906-1907 Box 7 1908-1909 Box 8 1910 Box 9 1911-1912 Box 10 1913-1915 Box 11 1916-1918 Box 12 TR’s Family’s Personal and Business Correspondence, and letters about TR post- January 6th, 1919 (TR’s death). A. From TR Abbott, Ernest H[amlin] TLS, Feb. 3, 1915 (New York), 1 p. Abbott, Lawrence F[raser] TLS, July 14, 1908 (Oyster Bay), 2 p. ALS, Dec. 2, 1909 (on safari), 4 p. TLS, May 4, 1916 (Oyster Bay), 1 p. TLS, March 15, 1917 (Oyster Bay), 1 p. Abbott, Rev. Dr. Lyman TLS, June 19, 1903 (Washington, D.C.), 1 p. TLS, Nov. 21, 1904 (Washington, D.C.), 1 p. TLS, Feb. 15, 1909 (Washington, D.C.), 2 p. Aberdeen, Lady ALS, Jan. 14, 1918 (Oyster Bay), 2 p. Ackerman, Ernest R. TLS, Nov. 1, 1907 (Washington, D.C.), 1 p. Addison, James T[hayer] TLS, Dec. 7, 1915 (Oyster Bay), 1p. Adee, Alvey A[ugustus] TLS, Oct. -

The China Relief Expedition Joint Coalition Warfare in China Summer 1900

07-02574 China Relief Cover.indd 1 11/19/08 12:53:03 PM 07-02574 China Relief Cover.indd 2 11/19/08 12:53:04 PM The China Relief Expedition Joint Coalition Warfare in China Summer 1900 prepared by LTC(R) Robert R. Leonhard, Ph.D. The Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory This essay reflects the views of the author alone and does not necessarily imply concurrence by The Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory (JHU/APL) or any other organization or agency, public or private. About the Author LTC(R) Robert R. Leonhard, Ph.D., is on the Principal Professional Staff of The Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory and a member of the Strategic Assessments Office of the National Security Analysis Department. He retired from a 24-year career in the Army after serving as an infantry officer and war planner and is a veteran of Operation Desert Storm. Dr. Leonhard is the author of The Art of Maneuver: Maneuver-Warfare Theory and AirLand Battle (1991), Fighting by Minutes: Time and the Art of War (1994), The Principles of War for the Informa- tion Age (1998), and The Evolution of Strategy in the Global War on Terrorism (2005), as well as numerous articles and essays on national security issues. Foreign Concessions and Spheres of Influence China, 1900 Introduction The summer of 1900 saw the formation of a perfect storm of conflict over the northern provinces of China. Atop an anachronistic and arrogant national government sat an aged and devious woman—the Empress Dowager Tsu Hsi. -

2013 Update and Boundary Increase Nomination

NPS Form 10-900 OMB No. 1024-0018 (Expires 5/31/2012) United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for individual properties and districts. See instructions in National Register Bulletin, How to Complete the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form. If any item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, architectural classification, materials, and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions. Place additional certification comments, entries, and narrative items on continuation sheets if needed (NPS Form 10-900a). 1. Name of Property historic name Fort Monroe (2013 Update and Boundary Increase) other names/site number VDHR #114-0002 2. Location street & number At the intersection of Mercury Boulevard and Mellon Street not for publication city or town Fort Monroe vicinity state Virginia code 51 county Hampton (Ind. City) code 650 zip code 23651 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act, as amended, I hereby certify that this x nomination request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property x meets does not meet the National Register Criteria. I recommend that this property be considered significant at the following level(s) of significance: x national statewide local ____________________________________ Signature of certifying official Date ____________ ____________________________________ ________________________________________ __ Title State or Federal agency/bureau or Tribal Government In my opinion, the property meets does not meet the National Register criteria. -

Descendants of Edmund Moody

Descendants of Edmund Moody 1 Edmund Moody b: 1495 in Bury St. Edmunds, Suffolk England ....... 2 Richard Moody b: 1525 in Moulton, Suffolk, England d: 28 Apr 1574 in Moulton, Suffolk, England ............. +Anne/Agnes Panell b: Abt. 1530 in England m: 04 Feb 1548 in Bury St. Edmund, Suffolk, England (St. Mary's) d: 14 Mar 1577 in Moulton, Suffolk, England ................. 3 George Moody b: 28 Sep 1560 in Moulton, Suffolk, England d: 21 Aug 1607 in Moulton, Suffolk, England ....................... +Margaret/Elizabeth Chenery b: Abt. 1561 in Kennett, Cambridgeshire, England m: 12 Oct 1581 in Kennett, Cambridgeshire, England d: 25 Jan 1603 in Moulton, Suffolk, England ........................... 4 John Moody b: 1593 in Moulton, Suffolk, England d: 1655 in Hartford, CT ................................. +Sarah Cox b: Abt. 1598 in England m: 08 Sep 1617 in Bury St. Edmund, Suffolk, England (St. James Parish) d: 04 Nov 1671 in Hadley, MA ..................................... 5 Samuel Moody b: Abt. 1635 in New England d: 22 Sep 1689 in Hadley, MA ........................................... +Sarah Deming b: 1636 in Wethersfield, Hartford Co., CT ............................................... 6 Sarah Moody b: 1659 in Hadley, MA d: 10 Dec 1689 ..................................................... +John Kellogg b: Dec 1656 d: 23 Dec 1680 ......................................................... 7 Joseph Kellogg b: 06 Nov 1685 d: Abt. 1786 ............................................................... +Abigail Smith b: 10 Oct 1692 m: in Mar 10 -

Theodore Roosevelt and the United States Battleship Maine

Theodore Roosevelt and the United States Battleship Maine Kenneth C. Wenzer The USB Maine exploded in Havana Harbor on February 15, 1898.1 Interest in this ship has endured for over 100 years and has, at times, provoked controversy. Apparently, some people still believe that a mine, surreptitiously planted by Spanish authorities, Cuban rebels, or other saboteurs, caused the initial detonation.2 A literary cottage industry of publications advocating different theories have muddied the waters, most notably Remembering the Maine published in 1995 and an article by National Geographic three years later.3 Under the auspices of Adm. Hyman G. Rickover, a team of seasoned researchers in the mid-1970s Assistant Secretary of the Navy Theodore proved in How the Battleship Maine Roosevelt, 1897–1898 Kenneth C. Wenzer is a historian who is affiliated with the Naval History and Heritage Command (Spanish-American War and World War I Documentary History Projects), Washington Navy Yard, Washington, DC. The opinions and conclusions expressed in this article are solely those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Department of the Navy or any other agency of the U.S. government. 1 The Maine was an armored cruiser and a second-class battleship. A gun from the Maine (now undergoing restoration) at the Washington Navy Yard has an inscribed plaque on the turret: “6 INCH- 30 CALIBER GUN FROM U.S. BATTLESHIP “MAINE” SUNK IN HAVANA HARBOR FEBRUARY 15, 1898.” Additionally, the “U.S.S.” prefix designation did not become official until 1907 by order of President Theodore Roosevelt.