Ee Cummings: Mirror and Arbiter of His

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

News, Notes, & Correspondence

News, Notes, & Correspondence The Theatre of E. E. Cummings Published In the News, Notes & Correspondence section of Spring 18, we re- ported that a new edition of The Theatre of E. E. Cummings was in the works, and—behold!—the book appeared on schedule at the beginning of 2013. This book, which contains the plays Him, Anthropos, and Santa Claus, along with the ballet Tom, provides readers with a handy edition of Cummings’ theatre works. The book also has an afterword by Norman Friedman, “E. E. Cummings and the Theatre,” which we printed in Spring 18 (94-108). The Thickness of the Coin In February, 2012 we received a card from Zelda and Norman Fried- man. They wrote: We are okay and want to tell you that the older we get the more skillful and wise E. E. Cummings becomes. Zelda has been trying to locate the line “love makes the little thickness of the coin” and came upon it accidentally in “hate blows a bubble of despair into” across the page in Complete Poems from “love is more thicker than forget”—the poem where she thought it might be. The Cummings-Clarke Papers at the Massachusetts Historical Society *In October 2012, Peter Steinberg of the Massachusetts Historical Society wrote to inform us that some of the Cummings-Clarke family papers con- taining “some materials by E. E. Cummings” had “recently been processed and made available for research.” Peter sent us the following “link to the finding aid / collection guide in hopes that you or your society members might be interested in learning about [the papers and] visiting the MHS”: http://www.masshist.org/findingaids/doc.cfm?fa=fa0367. -

E. E. Cummings

Center for the Book at the New Hampshire State Library BIBLIOGRAPHY January 2007 e. e. cummings Poetry 1 x 1. Holt, 1944; reprinted edited, afterword, by George James Firmage. Liveright, 2002. 1/20. Roger Roughton, 1936. 100 Selected Poems. Grove, 1958. 22 and 50 Poems. Edited by George James Firmage. Liveright, 2001. 50 Poems. Duell, Sloan & Pearce, 1940. 73 Poems. Harcourt, 1963. 95 Poems. Harcourt, 1958, reprinted edited by George James Firmage. Liveright, 2002. &. privately printed, 1925. (Contributor) Peter Neagoe, editor, Americans Abroad: An Anthology. Servire, 1932. Another E. E. Cummings. selected, introduced by Richard Kostelanetz, Liveright, 1998. (Chaire). Liveright, 1979. (Contributor) Nancy Cummings De Forzet. Charon's Daughter: A Passion of Identity. Liveright, 1977. Christmas Tree. American Book Bindery, 1928. Collected Poems. Harcourt, 1938. Complete Poems, 19101962. Granada, 1982. Complete Poems, 19231962. two volumes, MacGibbon & Kee, 1968; revised edition published in one volume as Complete Poems, 19131962. Harcourt, 1972. (Contributor) Eight Harvard Poets. L. J. Gomme, 1917. Etcetera: The Unpublished Poems of E. E. Cummings. Edited by Firmage and Richard S. Kennedy, Liveright, 1984. Hist Whist and Other Poems for Children. Edited by Firmage, Liveright, 1983. NH Center for the Book BIBLIOGRAPHY p. 2 of 4 e.e. cummings (January. 2007) In JustSpring. Little, Brown, 1988. is 5. Boni & Liveright, 1926; reprinted, Liveright, 1985. Love Is Most Mad and Moonly. AddisonWesley, 1978. May I Feel Said He: Poem. Paintings by Marc Chagall, Welcome Enterprises, 1995. No Thanks. Golden Eagle Press, 1935; reprinted, Liveright, 1978. Poems, 19051962. edited by Firmage, Marchim Press, 1973. Poems, 19231954. -

Edward Estlin Cummings

Classic Poetry Series Edward Estlin Cummings - poems - Publication Date: 2004 Publisher: PoemHunter.Com - The World's Poetry Archive 1(a... (a leaf falls on loneliness) 1(a le af fa ll s) one l iness Edward Estlin Cummings www.PoemHunter.com - The World's Poetry Archive 2 all in green All in green went my love riding on a great horse of gold into the silver dawn. Four lean hounds crouched low and smiling the merry deer ran before. Fleeter be they than dappled dreams the swift red deer the red rare deer. Four red roebuck at a white water the cruel bugle sang before. Horn at hip went my love riding riding the echo down into the silver dawn. Four lean hounds crouched low and smiling the level meadows ran before. Softer be they than slippered sleep the lean lithe deer the fleet flown deer. Four fleet does at a gold valley the famished arrow sang before. Bow at belt went my love riding riding the mountain down into the silver dawn. Four lean hounds crouched low and smiling the sheer peaks ran before. Paler be they than daunting death the sleek slim deer the tall tense deer. Four tall stags at the green mountain the lucky hunter sang before. All in green went my love riding on a great horse of gold into the silver dawn. Four lean hounds crouched low and smiling my heart fell dead before. Edward Estlin Cummings www.PoemHunter.com - The World's Poetry Archive 3 anyone lived in a pretty how town anyone lived in a pretty how town (with up so floating many bells down) spring summer autumn winter he sang his didn't he danced his did. -

Broj 19 Jun – Jul 2012

broj 19 jun – jul 2012. sadržaj uvodna re č ......................................................................................................................... 2 prevedena poezija Neli Zaks – Kad započne vreme bez slika ........................................................................ 4 Marko Stojkić – Neli Zaks ili mogućnost poezije nakon genocida ................................. 13 poezija Marina Adamović – To sam svojim očima zapisala ........................................................ 20 Bojan Marković – raff, klanice. ....................................................................................... 33 Ljiljana Tadić – Hladni prsti na ogledalu ........................................................................ 37 o poeziji Temat : E.E. Kamingz Ivana Maksić – Žensko pismo u poeziji E.E. Kamingza ................................................ 42 e.e. kamingz – Predgovor ................................................................................................ 69 e.e. kamingz – Izabrane pesme ........................................................................................ 70 e.e. kamingz – Prigovor izlaganju II ................................................................................ 80 Biografija ........................................................................................................................ 82 pisali su ............................................................................................................................. 84 1 uvodna reč Devetnaesti broj -

M OBAL IMTERPBETEB9S APPROACH to SELECTED

An oral interpreter's approach to selected poems by E. E. Cummings Item Type text; Thesis-Reproduction (electronic) Authors Holmes, Susanne Stanford, 1941- Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 07/10/2021 02:44:40 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/318940 m OBAL IMTERPBETEB9 S APPROACH TO SELECTED POEMS BY E, E. CUMMINGS "by Susanne Stanford Holmes A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the DEPARTMENT OF SPEECH In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS t- In The Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 19 6 4 STATEMENT BY AUTHOR This thesis has been submitted in partial fulfillment of requirements for an advanced degree at The University of Arizona and is deposited in the University Library to be made available to borrowers under rules of the Library. Brief quotations from this thesis are allowable with out special permission, provided that accurate acknowledgment of source is made. Requests for permission for extended quotation from or reproduction of this manuscript in whole or in part may be granted by the head of the major department or the Dean of the Graduate College when in his judgment the proposed use of the material is in the interests of scholar ship. In all other instances, however, permission must be obtained from the author. -

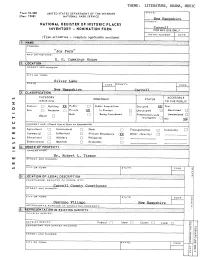

New^ Hampshire. Nnaamnn ——— O

THEME: LITERATURE, DRAMA, MUSIC Form 10-300 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR (Dec. 1968) NATIONAL PARK SERVICE New Hampshire COUN TY: NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES Carroll INVENTORY - NOMINATION FORM FOR NPS USE ONLY EN TRY NUMBER (Type all entries — complete applicable sections) 'joy Farm' AND/OR HISTORIC: E. E. Cummings House STREET AND NUMBER: CITY OR TOWN: Silver Lake New^ Hampshire. CATEGORY ACCESSIBLE OWNERSHIP STATUS (Check One) TO THE PUBLIC District n Bui Iding Public a Public Acquisition: Occupied XiXJ Yes: Site n Structure a Private m In Process Unoccupied || Restricted Both Being Considered Preservation work Unrestricted Object n in progress || No: PRESENT USE (Check One or More as Appropriate) Agricultural [ ] Government [ | Park Transportation | | Comments o Commercial Q Industrial Q Private Residence Other (Specify) n ——— Educational Q Military Q Religious Entertoinment Q] Museum | | Scientific OWNERS NAME: Mr. Robert L. Timmer STREET AND NUMBER: Cl TY OR TOWN: COURTHOUSE, REGISTRY OF DEEDS, ETC: Carroll County Courthouse STREET AND NUMBER: CITY OR TOWN: Ossippe Village New Hampshire APPROXIMATE ACREAGE OF NOMINATED PROPERTY: TITLE OF SURVEY: DATE OF SURVEY: Federal |~~1 State County Local DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS: STREET AND NUMBER: CITY OR TOWN: CONDITION (Check One) Excellent D Good Q Fair K Deteriorated Q R uins a Unexposed a (Check One) (Check One) INTEGRITY Altered ^3 Unaltered a Moved a Original Site fiQ The main house at "joy Farm" is a one-and-a-half story, white clapboarded structure with two interior chimnies. Its modified gable roof is flattened along the ridge to form a deck enclosed by a railing. -

American Poetry the Twentieth Century

AMERICAN POETRY THE TWENTIETH CENTURY VOLUME TWO E. E. Cummings to May Swenson THE LIBRARY OF AMERICA Contents E. E. CUMMINGS (1894-1962) "All in green went my love riding," 1 "in Just- / spring when the world is mud-," 2 "Tumbling-hair / picker of buttercups," 3: "Humanity i love you," 3 "O sweet spontaneous," 4 "stinging / gold swarms," 5 ' "between green / mountains," 6 "Babylon slim / -ness of," 6 "ta / ppin / g / toe," 7 "Buffalo Bill 's / defunct," 7 "the Cambridge ladies who live in furnished souls," 8 "god pity me whom(god distinctly has)," 8 "Dick Mid's large bluish face without eyebrows," 9 "Spring is like a perhaps hand," 9 POEM,OR BEAUTY HURTS MR. VINAL, 10 "she being Brand," 12 "on the Madam's best april the," 13 MEMORABILIA, 14 "next to of course god america i," 15 "lis / -ten // you know what i mean when," 15 "my sweet old etcetera," 16 "Among / these / red pieces of," 17 "in spite of everything," 18 "since feeling is first," 18 "i sing of Olaf glad and big," 18 "twi- / is :Light bird," 20 _ "a clown's smirk in the skull,of a baboon," 20 "somewhere i have never travelled,gladly beyond," 21 "r-p-o-p-h-e-s-s-a-g-r," 22 "the boys i mean are not refined," 22 "as freedom is a breakfastfood," 23 "anyone lived in a pretty how town," 24 "my father moved through dooms of love," 25 "plato told," 27 "pity this busy monster,manunkind," 28 "a grin without a," 29 xi xii CONTENTS H. -

E. E. Cummings Biography

E. E. Cummings Biography http://famouspoetsandpoems.com/poets/e__e__cummings/biography Edward Estlin Cummings was born October 14, 1894 in the town of Cambridge Massachusetts. His father, and most constant source of awe, Edward Cummings, was a professor of Sociology and Political Science at Harvard University. In 1900, Edward left Harvard to become the ordained minister of the South Congregational Church, in Boston. As a child, E.E. attended Cambridge public schools and lived during the summer with his family in their summer home in Silver Lake, New Hampshire. (Kennedy 8-9) E.E. loved his childhood in Cambridge so much that he was inspired to write disputably his most famous poem, "In Just-" (Lane pp. 26-27) Not so much in, "In Just-" but Cummings took his father's pastoral background and used it to preach in many of his other poems. In "you shall above all things be glad and young," Cummings preaches to the reader in verse telling them to love with naivete and innocence, rather than listen to the world and depend on their mind. Enlarge Picture Attending Harvard, Cummings studied Greek and other languages (p. 62). In college, Cummings was introduced to the writing and artistry of Ezra Pound, who was a large influence on E.E. and many other artists in his time (pp. 105-107). After graduation, Cummings volunteered for the Norton-Haries Ambulance Corps. En-route to France, Cummings met another recruit, William Slater Brown. The two became close friends, and as Brown was arrested for writing incriminating letters home, Cummings refused to separate from his friend and the two were sent to the La Ferte Mace concentration camp. -

EDWARD ESTLIN CUMMINGS (1894-1962) - Poetry, Prose and Politics Or La Salle Enorme Revisited

EDWARD ESTLIN CUMMINGS (1894-1962) - Poetry, Prose and Politics or La Salle Enorme Revisited. Cummings has been regarded as one of the leading lyricists America has produced. His writing is well known for its typographical eccentricity. Neither of these aspects is my primary concern but when they intrude upon quotations (as they inevitably will) I ask that they at least be tolerated, if not appreciated. Cumming's novel The Enormous Room is about politics - not party politics nor petty local government-type politics, but petty world politics. The novel is only a 'novel' because it doesn't give the actual names of in- dividuals involved, otherwise it is a piece of documentary prose. In April 1917 Cummings and his friend Slater Brown joined the Norton-Har/es Amb- ulance Corps (an American volunteer unit serving in France). On September 21st, as a result of some letters of Brown being intercepted by a French censor, both Cummings and Brown were arrested and moved to La Ferte Mace detention/concentration camp. Cummings was not released until December 19th and then only as a result of desperate letters written by his father to the President of the United States. The Enormous Room is con- cerned with the seventy-odd men who lived in the eighty foot by forty foot room at the prison, and the manner in which they reacted to the confinement and torture. One of the most amazing aspects the two Americans noticed was their excitement at being among such a variety of characters. After his arrival and reintroduction to Brown (who had been moved independently and arrived before Cummings) Cummings asks whether or not they are in an asylum. -

News, Notes, & Correspondence a New Edition of a Miscellany

News, Notes, & Correspondence A New Edition of A Miscellany Revised Long out of print, E. E. Cummings: A Miscellany Revised (October House, 1965) has been republished by Liveright as E. E. Cummings: A Miscellany. Apart from being redesigned and reset in a new typeface, little has changed from the 1965 edition. As before, the book lacks a sorely-needed index, and has no new notes and no new introduction. (The publishers have retained Firmage’s cursory 1965 introduction and Cummings’ very short foreword to the first 1958 edition.) One welcomes the republication of the volume while regretting the lack of updated scholarly content. And curiously, the back cover of the new edition classifies this collection of essays and hu- morous squibs as “Poetry.” A Norton Critical Edition, E. E. Cummings: Selected Poetry Milton Cohen has edited a new volume in the Norton Critical Editions se- ries, called E. E. Cummings: Selected Works, with a publication date in 2019, the 125th anniversary of Cummings’ birth. The volume features an introduction, an annotated selection of poems from every collection of Cummings’ poems (with the exception of the posthumous Etcetera), and critical responses and articles, as well as excerpts from Him, The Enormous Room, and i: six nonlectures. The volume also features eight black and white reproductions of Cummings’ artwork, as well as a small group of letters, two pages of the aphorisms he called “Jottings,” and a selection of critical essays, a chronology, and a bibliography. The reproductions of Cummings’ art are prefaced by an “Overview” by Cohen, while the critical essays are fronted by a preface by Michael Webster. -

I He Norton Anthology Or Poetry FOURTH EDITION

I he Norton Anthology or Poetry FOURTH EDITION •••••••••••< .•' .'.•.;';;/';•:; Margaret Ferguson > . ' COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY >':•! ;•/.'.'":•:;•> Mary Jo Salter MOUNT HOLYOKE COLLEGE Jon Stallworthy OXFORD UNIVERSITY W. W. NORTON & COMPANY • New York • London Contents PREFACE TO THE FOURTH EDITION lv Editorial Procedures ' Ivi ACKNOWLEDGMENTS " lix VERSIFICATION lxi Rhythm lxii Meter lxii Rhyme lxix Forms Ixxi Basic Forms Ixxi Composite Forms lxxvi Irregular Forms Ixxvii Open Forms or Free Verse lxxviii Further Reading lxxx GEDMON'S HYMN (translated by John Pope) 1 FROM BEOWULF (translated by Edwin Morgan) 2 RIDDLES (translated by Richard Hamer) 7 1 ("I am a lonely being, scarred by swords") 7 2 ("My dress is silent when I tread the ground") 8 3 ("A moth ate words; a marvellous event") 8 THE WIFE'S LAMENT (translated by Richard Hamer) 8 THE SEAFARER (translated by Richard Hamer) 10 ANONYMOUS LYRICS OF THE THIRTEENTH AND FOURTEENTH CENTURIES 13 Now Go'th Sun Under Wood 13 The Cuckoo Song 13 Ubi Sunt Qui Ante Nos Fuerunt? 13 Alison 15 Fowls in the Frith 16 • I Am of Ireland 16 GEOFFREY CHAUCER (ca. 1343-1400) 17 THE CANTERBURY TALES 17 The General Prologue 17 The Pardoner's Prologue and Tale 37 The Introduction 37 The Prologue 38 VI • CONTENTS The Tale 41 The Epilogue 50 From Troilus and Criseide 52 Cantus Troili 52 LYRICS AND OCCASIONAL VERSE 52 To Rosamond 52 Truth 53 Complaint to His Purse 54 To His Scribe Adam 5 5 PEARL, 1-5 (1375-1400) 55 WILLIAM LANGLAND(fl. 1375) 58 Piers Plowman, lines 1-111 58 CHARLES D'ORLEANS (1391-1465) 62 The Smiling Mouth 62 Oft in My Thought 62 ANONYMOUS LYRICS OF THE FIFTEENTH CENTURY 63 Adam Lay I-bounden 63 I Sing of a Maiden 63 Out of Your Sleep Arise and Wake 64 I Have a Young Sister 65 I Have a Gentle Cock 66 Timor Mortis 66 The Corpus Christi Carol 67 Western Wind 68 A Lyke-Wake Dirge 68 A Carol of Agincourt 69 The Sacrament of the Altar 70 See! here, my heart 70 WILLIAM DUNBAR (ca. -

E. E. Cummings: Modernist Painter and Poet Author(S): Milton A

E. E. Cummings: Modernist Painter and Poet Author(s): Milton A. Cohen Source: Smithsonian Studies in American Art, Vol. 4, No. 2 (Spring, 1990), pp. 54-74 Published by: The University of Chicago Press on behalf of the Smithsonian American Art Museum Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/3108985 . Accessed: 05/04/2011 17:57 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at . http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=ucpress. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. The University of Chicago Press and Smithsonian American Art Museum are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Smithsonian Studies in American Art.