Monitoring and Evaluation of the Work of the King's

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

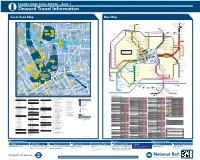

London Kings Cross Station – Zone 1 I Onward Travel Information Local Area Map Bus Map

London Kings Cross Station – Zone 1 i Onward Travel Information Local Area Map Bus Map 1 35 Wellington OUTRAM PLACE 259 T 2 HAVELOCK STREET Caledonian Road & Barnsbury CAMLEY STREET 25 Square Edmonton Green S Lewis D 16 L Bus Station Games 58 E 22 Cubitt I BEMERTON STREET Regent’ F Court S EDMONTON 103 Park N 214 B R Y D O N W O Upper Edmonton Canal C Highgate Village A s E Angel Corner Plimsoll Building B for Silver Street 102 8 1 A DELHI STREET HIGHGATE White Hart Lane - King’s Cross Academy & LK Northumberland OBLIQUE 11 Highgate West Hill 476 Frank Barnes School CLAY TON CRESCENT MATILDA STREET BRIDGE P R I C E S Park M E W S for Deaf Children 1 Lewis Carroll Crouch End 214 144 Children’s Library 91 Broadway Bruce Grove 30 Parliament Hill Fields LEWIS 170 16 130 HANDYSIDE 1 114 CUBITT 232 102 GRANARY STREET SQUARE STREET COPENHAGEN STREET Royal Free Hospital COPENHAGEN STREET BOADICEA STREE YOR West 181 212 for Hampstead Heath Tottenham Western YORK WAY 265 K W St. Pancras 142 191 Hornsey Rise Town Hall Transit Shed Handyside 1 Blessed Sacrament Kentish Town T Hospital Canopy AY RC Church C O U R T Kentish HOLLOWAY Seven Sisters Town West Kentish Town 390 17 Finsbury Park Manor House Blessed Sacrament16 St. Pancras T S Hampstead East I B E N Post Ofce Archway Hospital E R G A R D Catholic Primary Barnsbury Handyside TREATY STREET Upper Holloway School Kentish Town Road Western University of Canopy 126 Estate Holloway 1 St. -

Whitechapel Mile End Bow Road Bow Church Stepney Green Aldgate

Barclays Cycle Superhighway Route 2 Upgrade This map shows some of the main changes proposed along the route. For detailed proposals, visit tfl.gov.uk/cs2upgrade No right turn from Whitechapel Road Bus lane hours of operation into Stepney Green changed to Mon-Sat, 4pm-7pm No right turn from between Vallance Road and Whitechapel High Street Cambridge Heath Road into Leman Street N ST. BOTOLPH Whitechapel Stepney Green STREET VALLANCE ROAD VALLANCE GLOBE ROAD GLOBE OSBORN STREET Aldgate STREETCOMMERCIAL CAMBRIDGE HEATH ROAD WHITECHAPEL ROAD City of London Aldgate scheme COMMERCIAL ROAD The Royal London Aldgate Hospital East FIELDGATE STREET NEW ROAD LEMAN STREET LEMAN SIDNEY STREET STEPNEY GREEN STEPNEY MANSELL STREET MANSELL Continued below Continued No right turn from Mile End Road into Burdett Road NORTHERN APPROACH NORTHERN RIVER LEA RIVER Queen Mary University of London FAIRFIELD ROAD FAIRFIELD GROVE ROAD GROVE COBORN ROAD COBORN Continued above CS2 continues MILE END ROAD BOW ROAD HIGH STREET to Stratford Mile End Bow Road Bow Church BROMLEY HIGH STREET No right turn from TUNNEL CAMPBELL ROAD CAMPBELL BURDETTROAD HARFORD STREET HARFORD REGENT’S CANAL Burdett Road into Bow Road MORNINGTON GROVE BLACKWALL Kerb-separated cycle track New bus stop Major upgrade to junction Changes to be proposed under Vision for Bow scheme Wand-separated cycle lane Bus stop removed Other road upgrade scheme . -

Mile End Old Town, 1740-1780: a Social History of an Early Modern London Suburb

REVIEW ESSAY How Derek Morris and Kenneth Cozens are rewriting the maritime history of East London North of the Thames: a review Derek Morris, Mile End Old Town, 1740-1780: A Social History of an Early Modern London Suburb. 1st ed, 2002; 2nd ed., The East London History Society, 2007; a new edition in process to be extended back in time to cover from 1660; Derek Morris and Ken Cozens, Wapping, 1600-1800: A Social History of an Early Modern London Maritime Suburb. The East London History Society, 2009; Derek Morris, Whitechapel 1600-1800: A Social History of an Early Modern London Inner Suburb. The East London History Society, 2011; £12.60 and £3:50 p&p (overseas $18.50), http://wwww.eastlondonhistory .org.uk In three books published to date, two London-based researchers, Derek Morris and Kenneth Cozens, have set about the task of challenging many deeply-held stereotypes of London’s eastern parishes in the eighteenth century. With meticulous attention to detail, and with sure control of a wide range of archives, they have produced three highly-recommended works. The books Mile End and Wapping are in very short supply, if not by the time of this review, only available on the second-hand market. In Whitechapel, with the completion of the first phase of their research, they have ignored the restrictions imposed by parish boundaries: they have begun to draw conclusions about the nature of society in these areas in the eighteenth century. This is welcome for a number of reasons. But chief among these is that for too long historians have relied on a series of stereotypes with the emphasis on poverty, crime and “dirty industries,” to portray these eastern parishes, when in fact the emphasis should be on the important role played by local entrepreneurs in London’s growing economy and worldwide trading networks. -

Of the CAMDEN HISTORY SOCIETY No 197 May 2003 the Archaeology

No 195 of the CAMDEN HISTORY SOCIETY Jan 2003 the Institution Cottage, Swains Lane, tucked behind Lighting up Camden the Highgate Literary & Scientific Institution, still Thurs. 16 January, 7.30pm sporting a ceiling gas lamp. Bloomsbury Central Baptist Church (in the Church itself) As it happens, two of the old component parts of 235 Shaftesbury Avenue, WC2 Camden were at the forefront of municipal supply of (Bottom end of Gower Street) electricity - both were vestries which had been very dissatisfied with the operations of the various private We now take lighting, public and domestic, for granted. gas companies. Enabled by Act of Parliament to set up It is difficult to imagine our streets at night lit only by their own generating stations, St Pancras was the first oil or gas lamps and without the aid of shop window in the London field, obtaining an Electric Lighting illumination and the generally brighter night sky that Order in 1883, and Hampstead was not far behind. we have today in London. Electricity transformed our The first experiments by St Pancras consisted of arc neighbourhoods and made them safer, but the enor- lights placed centrally along the centre of Tottenham mity of the task may be imagined. Court Road, and a large stretch of Euston Road. Electricity also made a vast difference in lighting at The story of the development of electrical supply in home, where gas or oil supplies were supplemented Camden is the subject of our January talk, to be given by candles. A visit to Sir John Soane's Museum on by Dr Brian Bowers. -

Chief Executive's Report

Report to: Board of Directors (Public) Paper number: 1.7 Report for: Information Date: 28 January 2021 Report authors: Various Report of: Angela McNab, Chief Executive FoI status: Report can be made public Strategic priority Early and effective intervention supported: Cultural pillar We are connected Supported: Title: Chief Executive’s Report Executive Summary This report provides updates on a number of key meetings with staff and external stakeholders and information on key national developments. In addition, this report provides news of internal events and media interest. Use of the Trust seal is also reported. Recommendations to the Board The Board of Directors is requested to: • RECEIVE and ACCEPT the contents of this report for information; and • RATIFY the reported use of the Trust Seal. CHIEF EXECUTIVE’S REPORT GENERAL UPDATE Management of the Covid-19 Pandemic The Trust is actively managing a number of Covid-19 outbreaks on its wards. A review of our approach has been undertaken, including looking at practice in other trusts to ensure we are following best practice. We are seeing a recent slight increase in Covid-19 related staff absence and this is being managed appropriately according to policy and guidance. Covid- 19 LFT testing is in place for ‘patient facing’ staff. Oversight is maintained through ‘Gold Command’ meetings that take place three times each week (or more frequently if required). Our staff continue to provide psychological support for colleagues across the local health system as part of the health and wellbeing agenda and this is well received. Further details are provided within the Covid-19 Pandemic Wave Update later on this meeting’s agenda. -

) • Anciy Gete H Actien C:Ha

@ © Q~prfANI 7 2 ge P.cc • ln youa XO-yage Ilaeciai Saayye4 by oag yhotograyhert Staart Liytoa, 4irector oa a 4eqreloyiag eogayaayv Geral4 Leqria, archltect aa4 Nick Wates, a aorgaer sfiaattersc lea4er. What 4o theli'see through the ) • least Featare ye 14e Free to 52,000 homes No. 33 Thursday, November 4, 1002 Also st selected newssgents, prlce 5p New Journal brings joy... Anciy gete h S • Gas bill • Weekea4 act ie n c:ha IP Tv twr CASH snd cheques Iellemof klndudsheb put hls moneywhere • Vae exe ee hsve come pourlng " Thank you f o r hls mouth lm • Jobs I n for the N e w prlntlng an artlcle As soon as he aaw 4iesel Journays wheel. such as thls snd our fmnt page, he chslr sppesl on wlsh Andrew well msde s generous ylS/16 Motogs yle behalf of dlsabled from me,u ssld one ofter. Arldrew CrCoatw Somers Town gent. Camden S p orts Joumsl r e adem A csller from Prlm Counca held an were clesrly moved ross Hlfl promlasd emergency meetlng WalkahastIoadat? by our front page to maks up the sfter resdlng the story of Andrew's bslance on whstever story snd offemd to CAMDEN ceald be wltbeut bucecaad wltb only afcw paght waa ralsed. And a buy the wheelchatr tubes on Monday. Tnmcpart unleuc me prcparlug Ia for Andy outrlght Iakc ctrlke actleu la cuppert of the hcaltb ualeax Now a speclafly bullt penaloner sent R5 cash. Sut by thst tlme the RouudIbe-clock pickeic at Chalk Ferm garageNia wheelchalr to plsy smount needed hsd ensurec complete shutdown ofbuc routes46,24, 31 aud hls fsvourite gsme already been sub 63. -

Correspondence. Shoreditch, Battersea, Wandsworth, and Greenwich

THE SERVICES.-ROYAL SOCIETY OF MEDICINE 857 admissions averaged 15, against nine, 13, and nine in the ARMY MEDICAL SERVICE. three months. was most preceding Erysipelas proportionally (tI The undermentioned Colonels are placed on retired pay :— prevalent in Finsbury, Shoreditch, Bethnal Green, Stepney, James Magill, C.B. (dated Sept. 6th, 1907); and William A. Bermondsey, and Woolwich. The 25 cases of puerperal May, C B. (dated Sept. 18th, 1907). fever notified during the month included five in Southwark, The undermentioned Lieutenant-Colonels from the Royal five in Lambeth, three in Stepney, and two each in Fulham, Army Medical Corps to be Colonels : Douglas Wardrop, vice and Wandsworth. Of the 13 cases Hackney, Bermondsey, A. W. P. Inman, placed on half-pay (dated August 14th, of cerebro-spinal meningitis notified during the month, two 1907); George T. Goggin, vice J. Magill, C.B. (dated belonged to Shoreditch, two to Bethnal Green, two to Stepney, Sept. 6th, 1907); and John M. Jones, vice W. A. May, C.B. two to Camberwell, and one each to Chelsea, Bermondsey, (dated Sept. 18th, 1907). Lambeth, Battersea, and Lewisham. The mortality statistics in the table relate to the deaths ROYAL ARMY MEDICAL CORPS. of persons actually belonging to the various boroughs, the Captain Harry B. Connell, from the Seconded List, to be deaths occurring in institutions having been distributed Captain (dated August 28th, 1907). Lieutenant-Colonel G. T. among the several boroughs in which the deceased persons Goggin, Administrative Medical Officer at Belfast, has been had previously resided. During the four weeks ending appointed Principal Medical Officer of the Western Command August 31st the deaths of 4102 persons belonging to London (Chester), vice Colonel H. -

London Assembly Economy Committee – 21 March 2017

Appendix 1 London Assembly Economy Committee – 21 March 2017 Transcript of Item 6 – Local News Provision Fiona Twycross AM (Chair): That brings us to today’s main item, a discussion on local news provision in London. Firstly, can I ask Members to agree the terms of reference for the discussion? They are: to examine how local news provision in London has changed over the past decade and what is driving that change and to consider the impact of these changes on the ability of Londoners to remain reliably informed on key issues in their local areas. I would now like to welcome our guests. We do have slightly more guests than we normally would, but there were a whole range of different angles on this and so thank you, everybody, for coming along. We have Laura Davison, who is National Organiser from the National Union of Journalists (NUJ); Hannah Walker, who is London Managing Director and Editor-in-Chief of the London Weekly News; Ceri Gould, Editor-in-Chief of the Trinity Mirror; and Professor Angela Phillips from Goldsmiths, University of London. Michael MacFarlane [Head of BBC London & BBC South East] is going to join us at about 11.00 am. Eric Gordon is here; he is Editor of the Camden New Journal (CNJ) group. Martin Hoscik is a journalist and commentator, notably of MayorWatch. We are also expecting Linda Quinn, Editor-in-Chief of the Brixton Bugle, who, again, is expected at about 11.00 am. That brings us to the start of the questioning and to one of the most topical questions in London around media at the moment: will the appointment of a serving politician as editor of the [London] Evening Standard affect the news coverage in London? Would anybody like to start? Laura Davison (National Organiser, National Union of Journalists): I am happy to kick off. -

Semester Three May - August 2019

SEMESTER THREE MAY - AUGUST 2019 Your EVENT GUIDE MAKE THE MOST OF YOUR MEMBERSHIP BY USING THE SOCIAL SPACES AND ATTENDING EVENTS ACROSS ALL LONDON CHAPTERS CHAPTER KINGS CROSS “I made loads of friends who live here, the location is great and the staff are great too.” Franciscan from Spain Kings College London CHAPTER HIGHBURY “It’s really good to TO YOUR SEMESTER THREE EVENT GUIDE... have a gym and cinema in my building.” s you know, being a member Kaivel from China Welcomeof Chapter means you have UCL exclusive access to the incredible social spaces at Aall Chapter locations across London. Perhaps you want to watch a film with friends at Chapter Highbury, have a sky-high drink in the 32nd floor bar at Member Chapter Spitalfields, or attend a fitness class at Chapter Kings Cross. Simply show your Chapter member card at reception or to security on the door and they’ll let you through. Being a resident of Chapter means you enjoy exclusive Benefitaccess to all of our locations across London.s And it’s not just the social spaces that you have access to, you can attend all the exciting events at the other CHAPTER SPITALFIELDS Chapters too. “It’s close to my university, the tube station and it’s very central. Everybody is very CHAPTER IS YOUR HOME AND YOU HAVE friendly and the events are a great way to interact with ACCESS TO EVERYTHING ON OFFER. everyone. All of the staff have been really helpful.” Victoria from France In this guide, you’ll find your event Istituto Marangoni plan for Semester 3. -

The East End in Colour 1960–1980 the East End in Colour 1960–1980

THE EAST END IN COLOUR 1960–1980 THE EAST END IN COLOUR 1960–1980 The photographs of David Granick from the collections of Tower Hamlets Local History Library & Archives edited by CHRIS DORLEY-BROWN We are an indie publisher making small collectable photobooks out of East London. Our goal is to make books that are both beautiful and accessible. Neither aloof nor plain. We want both collectors and everyday folk to keep them in neat piles on wooden shelves. We are Ann and Martin and have two dogs, Moose and Bug, both of whom hate art. East London is where we nurture our ideas, walk the dogs and meet people more talented than ourselves. Thank you for supporting us. You can find more of our books at: www.hoxtonminipress.com TOWER HAMLETS LOCAL HISTORY LIBRARY & ARCHIVES On his death in 1980, David Granick’s slides were deposited at his local public Visit us library on Bancroft Road, just a few minutes away from where he lived in Stepney. We hold many exhibitions and events, always free of charge, highlighting many At that time, the large Victorian building was the central lending library for the different aspects of East End history. But even if you can’t visit in person, feel free borough of Tower Hamlets with just one room for local history. Now, the whole to ask a question, add us on social media or sign up to our newsletter. For further building is dedicated to collecting, capturing and preserving materials and re- information about David Granick, our upcoming events and opening times, sources illustrating the amazing history of the borough. -

3.1 Report For: Information Date: 10 December 2019 Report Authors: Various Report Of: Chief Executive Foi Status: Report Can Be Made Public

Report to: Council of Governors Paper number: 3.1 Report for: Information Date: 10 December 2019 Report authors: Various Report of: Chief Executive FoI status: Report can be made public Strategic priority Early and effective intervention. supported: Cultural pillar We are connected. Supported: Title: Chief Executive’s Report Executive Summary This report provides updates on a number of key meetings with staff and external stakeholders and information on key national developments. In addition, this report provides news of internal events and media interest, and details any use of the Trust seal. Recommendations to the Board The Board of Directors is requested to: RECEIVE and ACCEPT the contents of this report for information. Risk Implications The paper covers developments in areas already identified within the risk register. Finance Implications There are no specific financial implications resulting from this update report. CHIEF EXECUTIVE’S REPORT GENERAL UPDATE The Trust has continued to progress its longstanding work to reduce length of stay and support alternatives to admission. I am pleased to say that, following the recent surge of A&E referrals, we now are now back on our previous low figure of out of area placements and generally managing demand locally. I am grateful to all staff who have worked so hard to manage the recent increased demand. In January we hope to be starting the innovative partnership model between the London Ambulance Service and mental health support whereby a mental health nurse will go out to patients who call assistance reporting they are in crisis. This model was trialled in South London and significantly reduced the number of people who were conveyed to an Emergency Department; providing better care for patients. -

Bakerloo, Central and Victoria Lines Tube Depths

Bakerloo line Harrow & Wealdstone – Elephant & Castle Kenton Platform level 56 (metres relative to ground level) North Ground level Wembley Harrow & 48 Wembley (metres relative to sea level) Wealdstone Central 52 45 Willesden Kensal Green Junction 42 South Kenton Harlesden 40 Queen’s Park 43 38 38 Edgware Road Maida Vale 32 Marylebone Kilburn 31 Warwick 29 Regent’s Park Park Avenue Baker Street Oxford Circus Paddington 28 27 27 27 27 25 Piccadilly Circus Stonebridge 19 Park 24 Charing Cross 12 Embankment Lambeth Elephant & Waterloo 5 North Castle 4 3 3 Sea level (0m) Central line Ealing Broadway – Hainault Hainault 36 Fairlop Ealing West North 30 Acton Acton Ground level Broadway 33 33 33 (metres relative to sea level) Notting Hill Oxford Platform level Wanstead Barkingside Gate Queensway Marble Arch Circus Tottenham 29 (metres relative to ground level) 28 27 27 27 Court Road 25 Leytonstone Gants Hill Bond Street 25 Holborn 23 East 23 Chancery 25 Newbury Lancaster 22 Acton Lane Park Gate 12 20 19 18 St Paul’s Holland 17 Liverpool Leyton Park Bank Street Bethnal Green 15 Redbridge 14 14 14 14 Mile End 12 12 Shepherd’s Stratford White City Bush 4 7 6 Sea level (0m) Central line Ealing Broadway – Epping Epping 81 Theydon Bois 54 Buckhurst Hill 40 Debden 37 Ealing West North Acton Acton Ground level Broadway Woodford 33 33 33 (metres relative to sea level) 32 Notting Hill Oxford Platform level Gate Queensway Marble Arch Circus Tottenham (metres relative to ground level) 28 27 27 27 Court Road Leytonstone Bond Street 25 Holborn 23 Loughton