Beyond Flamenco: Ork

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rhythmic Foundation and Accompaniment

Introduction To Flamenco: Rhythmic Foundation and Accompaniment by "Flamenco Chuck" Keyser P.O. Box 1292 Santa Barbara, CA 93102 [email protected] http://users.aol.com/BuleriaChk/private/flamenco.html © Charles H. Keyser, Jr. 1993 (Painting by Rowan Hughes) Flamenco Philosophy IA My own view of Flamenco is that it is an artistic expression of an intense awareness of the existential human condition. It is an effort to come to terms with the concept that we are all "strangers and afraid, in a world we never made"; that there is probably no higher being, and that even if there is he/she (or it) is irrelevant to the human condition in the final analysis. The truth in Flamenco is that life must be lived and death must be faced on an individual basis; that it is the fundamental responsibility of each man and woman to come to terms with their own alienation with courage, dignity and humor, and to support others in their efforts. It is an excruciatingly honest art form. For flamencos it is this ever-present consciousness of death that gives life itself its meaning; not only as in the tragedy of a child's death from hunger in a far-off land or a senseless drive-by shooting in a big city, but even more fundamentally in death as a consequence of life itself, and the value that must be placed on life at each moment and on each human being at each point in their journey through it. And it is the intensity of this awareness that gave the Gypsy artists their power of expression. -

James Albert Michener (1907-97): Educator, Textbook Editor, Journalist, Novelist, and Educational Philanthropist--An Imaginary Conversation

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 474 132 SO 033 912 AUTHOR Parker, Franklin; Parker, Betty TITLE James Albert Michener (1907-97): Educator, Textbook Editor, Journalist, Novelist, and Educational Philanthropist--An Imaginary Conversation. PUB DATE 2002-00-00 NOTE 18p.; Paper presented at Uplands Retirement Community (Pleasant Hill, TN, June 17, 2002). PUB TYPE Opinion Papers (120) EDRS PRICE EDRS Price MF01/PC01 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Authors; *Biographies; *Educational Background; Popular Culture; Primary Sources; Social Studies IDENTIFIERS *Conversation; Educators; Historical Research; *Michener (James A); Pennsylvania (Doylestown); Philanthropists ABSTRACT This paper presents an imaginary conversation between an interviewer and the novelist, James Michener (1907-1997). Starting with Michener's early life experiences in Doylestown (Pennsylvania), the conversation includes his family's poverty, his wanderings across the United States, and his reading at the local public library. The dialogue includes his education at Swarthmore College (Pennsylvania), St. Andrews University (Scotland), Colorado State University (Fort Collins, Colorado) where he became a social studies teacher, and Harvard (Cambridge, Massachusetts) where he pursued, but did not complete, a Ph.D. in education. Michener's experiences as a textbook editor at Macmillan Publishers and in the U.S. Navy during World War II are part of the discourse. The exchange elaborates on how Michener began to write fiction, focuses on his great success as a writer, and notes that he and his wife donated over $100 million to educational institutions over the years. Lists five selected works about James Michener and provides a year-by-year Internet search on the author.(BT) Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best that can be made from the original document. -

A Comparison of the Piano and Guitar Versions of Isaac Albéniz's Spanish Suite Op

A COMPARISON OF THE PIANO AND GUITAR VERSIONS OF ISAAC ALBÉNIZ'S SPANISH SUITE OP. 47 by YI-YIN CHIEN A LECTURE-DOCUMENT Presented to the School of Music and Dance of the University of Oregon in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts November 2016 2 “A Comparison of the Piano and Guitar Versions of Isaac Albéniz’s Spanish Suite, Op. 47’’ a document prepared by Yi-Yin Chien in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Doctor of Musical Arts degree in the School of Music and Dance. This document has been approved and accepted by: Jack Boss, Chair of the Examining Committee Date: November 20th, 2016 Committee in Charge: Dr. Jack Boss, Chair Dr. Juan Eduardo Wolf Dr. Dean Kramer Accepted by: Director of Graduate Studies, School of Music and Dance © 2016 Yi-Yin Chien 3 CURRICULUM VITAE NAME OF AUTHOR: Yi-Yin Chien PLACE OF BIRTH: Taiwan DATE OF BIRTH: November 02, 1986 GRADUATE AND UNDERGRADUATE SCHOOLS ATTENDED: University of Oregon, School of Music and Dance Peabody Institute of the Johns Hopkins University Tainan National University of Arts DEGREES AWARDED: Doctor of Musical Arts, 2016, University of Oregon Master of Music, 2011, Peabody Institute of the Johns Hopkins University Bachelor of Music, 2009, Tainan National University of Arts AREAS OF SPECIAL INTEREST: Piano Pedagogy Music Theory PROFESSIONAL EXPERIENCE: College Piano Teaching, University of Oregon, School of Music and Dance, 09/2014 - 06/2015 Taught piano lessons for music major and non-major college students Graduate Teaching -

JAMES A. MICHENER Has Published More Than 30 Books

Bowdoin College Commencement 1992 One of America’s leading writers of historical fiction, JAMES A. MICHENER has published more than 30 books. His writing career began with the publication in 1947 of a book of interrelated stories titled Tales of the South Pacific, based upon his experiences in the U.S. Navy where he served on 49 different Pacific islands. The work won the 1947 Pulitzer Prize, and inspired one of the most popular Broadway musicals of all time, Rodgers and Hammerstein’s South Pacific, which won its own Pulitzer Prize. Michener’s first book set the course for his career, which would feature works about many cultures with emphasis on the relationships between different peoples and the need to overcome ignorance and prejudice. Random House has published Michener’s works on Japan (Sayonara), Hawaii (Hawaii), Spain (Iberia), Southeast Asia (The Voice of Asia), South Africa (The Covenant) and Poland (Poland), among others. Michener has also written a number of works about the United States, including Centennial, which became a television series, Chesapeake, and Texas. Since 1987, the prolific Michener has written five books, including Alaska and his most recent work, The Novel. His books have been issued in virtually every language in the world. Michener has also been involved in public service, beginning with an unsuccessful 1962 bid for Congress. From 1979 to 1983, he was a member of the Advisory Council to the National Aeronautics and Space Administration, an experience which he used to write his 1982 novel Space. Between 1978 and 1987, he served on the committee that advises that U.S. -

Coastal Iberia

distinctive travel for more than 35 years TRADE ROUTES OF COASTAL IBERIA UNESCO Bay of Biscay World Heritage Site Cruise Itinerary Air Routing Land Routing Barcelona Palma de Sintra Mallorca SPAIN s d n a sl Lisbon c I leari Cartagena Ba Atlantic PORTUGALSeville Ocean Granada Mediterranean Málaga Sea Portimão Gibraltar Seville Plaza Itinerary* This unique and exclusive nine-day itinerary and small ship u u voyage showcases the coastal jewels of the Iberian Peninsula Lisbon Portimão Gibraltar between Lisbon, Portugal, and Barcelona, Spain, during Granada u Cartagena u Barcelona the best time of year. Cruise ancient trade routes from the October 3 to 11, 2020 Atlantic Ocean to the Mediterranean Sea aboard the Day exclusively chartered, Five-Star LE Jacques Cartier, featuring 1 Depart the U.S. or Canada the extraordinary Blue Eye, the world’s first multisensory, underwater Observation Lounge. This state-of-the-art small 2 Lisbon, Portugal/Embark Le Jacques Cartier ship, launching in 2020, features only 92 ocean-view Suites 3 Portimão, the Algarve, for Lagos and Staterooms and complimentary alcoholic and nonalcoholic beverages and Wi-Fi throughout the ship. Sail up Spain’s 4 Cruise the Guadalquivir River into legendary Guadalquivir River, “the great river,” into the heart Seville, Andalusia, Spain of beautiful Seville, an exclusive opportunity only available 5 Gibraltar, British Overseas Territory on this itinerary and by small ship. Visit Portugal’s Algarve region and Granada, Spain. Stand on the “Top of the Rock” 6 Málaga for Granada, Andalusia, Spain to see the Pillars of Hercules spanning the Strait of Gibraltar 7 Cartagena and call on the Balearic Island of Mallorca. -

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Season 110, 1990-1991, Subscription

&Bmm HHH 110th Season 19 9 0-91 Boston Symphony Orchestra Seiji Ozawa, Music Director 90th Anniversary of Symphony Hall m<K Only The few will own an aldemars. Only the few will seek the exclusivity that comes with owning an Audemars Piguet. Only the few will recognize wn more than a century of technical in- f\Y novation; today, that innovation is reflected in our ultra-thin mech- Memars Piguet anical movements, the sophistica- tion of our perpetual calendars, and more recently, our dramatic new watch with dual time zones. Only the few will appreciate The CEO Collection which includes a unique selection of the finest Swiss watches man can create. Audemars Piguet makes only a limited number of watches each year. But then, that's something only the few will understand. SHREVECRUMP &LOW JEWELERS SINCE 1800 330BOYLSTON ST., BOSTON, MASS. 02116 (617) 267-9100 • 1-800-225-7088 THE MALL AT CHESTNUT HILL • SOUTH SHORE PLAZA Seiji Ozawa, Music Director Grant Llewellyn and Robert Spano, Assistant Conductors One Hundred and Tenth Season, 1990-91 Trustees of the Boston Symphony Orchestra, Inc. Nelson J. Darling, Jr., Chairman Emeritus J. P. Barger, Chairman George H. Kidder, President Mrs. Lewis S. Dabney, Vice-Chairman Archie C. Epps, Vice-Chairman Mrs. John H. Fitzpatrick, Vice-Chairman William J. Poorvu, Vice-Chairman and Treasurer David B. Arnold, Jr. Avram J. Goldberg Mrs. August R. Meyer Peter A. Brooke Mrs. R. Douglas Hall III Mrs. Robert B. Newman James F. Cleary Francis W. Hatch Peter C. Read John F. Cogan, Jr. Julian T. Houston Richard A. -

Luis Fernando Pérez Piano

LUIS FERNANDO PÉREZ Praised for his virtuosity, his colorful playing and his extraordinary and rare capability to comunicate straight forward to his public, Luis Fernando Pérez is considered to be one of the most excepcional artists of his generation and “The Renaissance of Spanish Piano” (Le Monde). Applauded unanimously by the world critics and owner of numerous prizes as the Franz Liszt (Italy) and the Granados Prize-Alicia de Larrocha prize (Barcelona), Luis Fernando is owner too of the Albeniz Medall, given to him for his outstanding interpretation of Iberia, considered by Gramophone Magazine as “one of the four mythical” (together with those of Esteban Sanchez, Alicia de Larrocha and Rafael Orozco). Luis Fernando belongs to this rare group of outstanding musicians who have been taught by legendary artists; with Dimitri Bashkirov and Galina Egyazarova, students of the great Alexander Goldenweiser - following a straight tradition after Liszt´s considered best student Siloti- further on with Pierre-Laurent Aimard and with the great spanish pianist Alicia de Larrocha and her assistant Carlota Garriga in the Marshall Academy in Barcelona. It is precisely in the Marshall Academy beside Larrocha where he specializes in the interpretation of Spanish Music, obtaining his Masters in Spanish Music Interpretation and where he also works all piano of Federico Mompou with his widow, Carmen Bravo. He has received also continuated lessons and masterclasses from great artists as Leon Fleisher, Andras Schiff, Bruno-Leonardo Gelber, Menahen Pressler, Fou Tsong and Gyorgy Sandor. He has collaborated with numerous orchestras as the Spanish National Orchestra, Montecarlo Filharmonic, Sinfonia Varsovia, Franz Liszt Chamber Orchestra, Filharmonia Baltycka, Enemble Kanazawa (Japan), Real Filarmonía de Galicia, OBC (Barcelona), BOS (Bilbao), Ensemble National de Paris, Brasil National Orchestra…and together with great conductors as Ros Marbá, Georges Tchitchinadze, Kazuki Yamada, Jesús López Cobos, Jean-Jacques Kantorow, Dimitri Liss, Paul Daniel, Rumon Gamba, Carlo Rizzi. -

Orquestra De Cadaqués Josep Vicent, Director

Orquestra de Cadaqués Josep Vicent, director La Orquesta de Cadaqués se formó en 1988 con unos objetivos claros: trabajar de cerca Graduado Cum Laude en el Conservatorio de Alicante y en el Amsterdam con los compositores contemporáneos vivos, recuperar un legado de música española Conservatory. Fue asistente de Alberto Zedda y Daniel Barenboim. Recibe el Primer olvidada e impulsar la carrera de solistas, compositores y directores emergentes. Premio de Interpretación de Juventudes Musicales, el Premio Vicente Monfort de las Júlia Gállego, solista Sir Neville Marriner, Gennady Rozhdestvensky o Philippe Entremont se convirtieron en Artes Ciudad de Valencia 2013 y el Premio Óscar Esplá Ciudad de Alicante. Es principales invitados, así como Alicia de Larrocha, Victoria de los Ángeles, Teresa Embajador Internacional de la “Fundación Cultura de Paz” presidida por D. Federico Berganza, Paco de Lucía, Ainhoa Arteta, Jonas Kaufmann, Olga Borodina y Juan Diego Mayor Zaragoza. Premio Los Mejores Diario LA VERDAD 2016. Excepcional solista Alicantina, fue miembro de la Joven Orquesta Nacional de Florez entre otros. Tras una amplia y temprana carrera como Solista-Director Artístico y su trabajo en la España y de la Gustav Mahler Jugendorchester, flauta Principal de la Oquesta En 1992 la orquesta impulsó el Concurso Internacional de Dirección. Pablo González, Orquesta del Concertgebouw (1998- 2004), inicia una imparable carrera internacional Sinfónica de Tenerife y de la Orquesta Sinfónica de Galicia. Galardonada con Gianandrea Noseda, Vasily Petrenko o Michal Nesterowicz han sido algunos de los frente a formaciones como: London Symphony, The World Orchestra, Paris Chamber el Premio de la Ciudad de París en 1994, el Primer Premio en el concurso de ganadores. -

Listening Program Script I

Non-Directed Music Listening Program Series I Non-Directed Music Listening Program Script Series I Week 1 Composer: Manuel de Falla (1876 – 1946) Composition: “Ritual Fire Dance” from “El Amor Brujo” Performance: Philadelphia Orchestra, Eugene Ormandy Recording: “Greatest Hits of The Ballet, Vol. 1” CBS XMT 45658 Day 1: This week’s listening selection is titled “Ritual Fire Dance”. It was composed by Manuel de Falla. Manuel de Falla was a Spanish musician who used ideas from folk stories and folk music in his compositions. The “Ritual Fire Dance” is from a ballet called “Bewitched By Love” and describes in musical images how the heroine tries to chase away an evil spirit which has been bothering her. Day 2: This week’s feature selection is “Ritual Fire Dance” composed by the Spanish writer Manuel de Falla. In this piece of music, de Falla has used the effects of repetition, gradual crescendo, and ostinato rhythms to create this very exciting composition. Crescendo is a musical term which means the music gets gradually louder. Listen to the “Ritual Fire Dance” this time to see how the effect of the ‘crescendo’ helps give a feeling of excitement to the piece. Day 3: This week’s featured selection, “Ritual Fire Dance”, was written by the Spanish composer Manuel de Falla in 1915. Yesterday we mentioned how the composer made use of the effect of gradually getting louder to help create excitement. Do you remember the musical term for the effect of gradually increasing the volume? If you were thinking of the word ‘crescendo’ you are correct. -

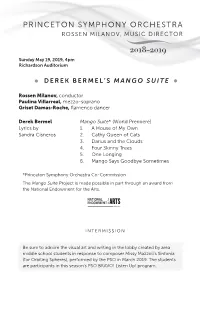

Mango Suite Program Pages

PRINCETON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA ROSSEN MILANOV, MUSIC DIRECTOR 2018–2019 Sunday May 19, 2019, 4pm Richardson Auditorium DEREK BERMEL’S MANGO SUITE Rossen Milanov, conductor Paulina Villarreal, mezzo-soprano Griset Damas-Roche, flamenco dancer Derek Bermel Mango Suite* (World Premiere) Lyrics by 1. A House of My Own Sandra Cisneros 2. Cathy Queen of Cats 3. Darius and the Clouds 4. Four Skinny Trees 5. One Longing 6. Mango Says Goodbye Sometimes *Princeton Symphony Orchestra Co-Commission The Mango Suite Project is made possible in part through an award from the National Endowment for the Arts. INTERMISSION Be sure to admire the visual art and writing in the lobby created by area middle school students in response to composer Missy Mazzoli’s Sinfonia (for Orbiting Spheres), performed by the PSO in March 2019. The students are participants in this season’s PSO BRAVO! Listen Up! program. Manuel de Falla El amor brujo Introducción y escena (Introduction and Scene) En la cueva (In the Cave) Canción del amor dolido (Song of Love’s Sorrow) El Aparecido (The Apparition) Danza del terror (Dance of Terror) El círculo mágico (The Magic Circle) A medianoche (Midnight) Danza ritual del fuego (Ritual Fire Dance) Escena (Scene) Canción del fuego fatuo (Song of the Will-o’-the-Wisp) Pantomima (Pantomime) Danza del juego de amor (Dance of the Game of Love) Final (Finale) El sombrero de tres picos (The Three-Cornered Hat), Suite No. 1 Introduction—Afternoon Dance of the Miller’s Wife (Fandango) The Corregidor The Grapes La vida breve, Spanish Dance No. 1 This concert is made possible in part through the support of Yvonne Marcuse. -

Music in Catalonia Today

MUSIC MUSIC IN CATALONIA TODAY CATALONIA'S MOST CHARACTERISTIC CONTRIBUTION TO UNIVERSAL MUSIC HAS BEEN ITS REPERTORY OF FOLKSONGS, ONE OF THE MOST BEAUTIFUL AND RICHEST IN EUROPE.IN CLASSICAL MUSIC, ALONGSIDE QUITE OUTSTANDING COMPOSERS, THERE IS AN EXTRAORDINARY LIST OF FIRST-RATE INTERNATIONAL PERFORMERS. SEBASTIA BENET I SANVICENS MUSICOLOGIST he music scene in Catalonia to- there is an extraordinary list of first-rate end of the nineteenth century. The mu- day has a remote ancestry which intemational performers. sic is played by a special band, the co- has fashioned its character down Pau Casals, father of the modern cello, bla, led by the tenora, an instrument to the present moment. In the course of contributed to a universal knowledge of which originated in Catalonia. The sar- this evolution we see that Catalonia's Catalan folk music by adopting the dana is a living dance, which people of most characteristic contribution to uni- beautiful tune "El cant dels ocells" as a al1 ages take part in at any celebration versal music has been its repertory of testimony of his cultural origin. Our during the year, and which has pro- folksongs, one of the most beautiful and popular music also includes a wide va- duced masterpieces composed by some richest in Europe. In classical music, riety of dances, in particular the sarda- of the best Catalan musicians, includ- alongside quite outstanding composers, na, Catalonia's national dance since the ing Pau Casals himself. Igor Stravinsky, MUSIC on a visit to Barcelona in 1924, was 1927-, which had a primarily classical recently, the conductors Salvador Mas filled with enthusiasm for a sardana repertoire and soon took their place in and Josep Pons, successful internatio- with music by Juli Garreta, a musician the European choral movement. -

JAM the Whole Chapter

INTRODUCTION TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgements ....................................................................................... 2 Introduction ................................................................................................... 3 The Man ...................................................................................................... 4-6 The Author ................................................................................................ 7-10 The Public Servant .................................................................................. 11-12 The Collector ........................................................................................... 13-14 The Philanthropist ....................................................................................... 15 The Legacy Lives ..................................................................................... 16-17 Bibliography ............................................................................................ 18-21 This guide was originally created to accompany the Explore Through the Art Door Curriculum Binder, Copyright 1997. James A. Michener Art Museum 138 South Pine Street Doylestown, PA 18901 www.MichenerArtMuseum.org www.LearnMichener.org 1 THE MAN THEME: “THE WORLD IS MY HOME” James A. Michener traveled to almost every corner of the world in search of stories, but he always called Doylestown, Pennsylvania his hometown. He was probably born in 1907 and was raised as the adopted son of widow Mabel Michener. Before he was thirteen,