The Only Thing Worse Than Being Blind Is Having Sight but No Vision. -Helen

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mathematics in the Modern Age - the 18Th Century: Crossing Bridges Transcript

Mathematics in the modern age - The 18th century: Crossing bridges Transcript Date: Wednesday, 4 October 2006 - 12:00AM Location: Barnard's Inn Hall MATHEMATICS IN THE MODERN AGE - THE 18TH CENTURY: CROSSING BRIDGES Professor Robin Wilson Introduction After Isaac Newton had published his celebrated PrincipiaMathematicain 1687 – the book that explained gravitation and how the planets move – his life changed for ever, and in a way that would also affect the nature of British mathematics for the next 150 years or so. His book was highly praised in Britain, even though few people could understand it, and the reclusive Newton was now a public figure. After spending a year as an ineffective Member of Parliament for Cambridge University – apparently he spoke only once, and that was to ask an official to open a window – Newton became Warden, and later Master, of the Royal Mint, living in the Tower of London, supervising the minting of coins, and punishing counterfeiters. He had now left Cambridge for good. In 1703 Newton’s arch-rival Robert Hooke died, with repercussions for both Gresham College where he was Gresham Professor of Geometry, and the Royal Society which still held its meetings in Sir Thomas Gresham’s former house. The rebuilding of the Royal Exchange after the Great Fire of 1666 had been costly, and attendances at Gresham lectures were then sparse, so proposals were made to save money by rebuilding the College on a smaller scale. Parliament was petitioned for approval, with only Robert Hooke, now frail and the only professor resident in the College, holding out against the plans. -

Algebraic Topology - Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia Page 1 of 5

Algebraic topology - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Page 1 of 5 Algebraic topology From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Algebraic topology is a branch of mathematics which uses tools from abstract algebra to study topological spaces. The basic goal is to find algebraic invariants that classify topological spaces up to homeomorphism, though usually most classify up to homotopy equivalence. Although algebraic topology primarily uses algebra to study topological problems, using topology to solve algebraic problems is sometimes also possible. Algebraic topology, for example, allows for a convenient proof that any subgroup of a free group is again a free group. Contents 1 The method of algebraic invariants 2 Setting in category theory 3 Results on homology 4 Applications of algebraic topology 5 Notable algebraic topologists 6 Important theorems in algebraic topology 7 See also 8 Notes 9 References 10 Further reading The method of algebraic invariants An older name for the subject was combinatorial topology , implying an emphasis on how a space X was constructed from simpler ones (the modern standard tool for such construction is the CW-complex ). The basic method now applied in algebraic topology is to investigate spaces via algebraic invariants by mapping them, for example, to groups which have a great deal of manageable structure in a way that respects the relation of homeomorphism (or more general homotopy) of spaces. This allows one to recast statements about topological spaces into statements about groups, which are often easier to prove. Two major ways in which this can be done are through fundamental groups, or more generally homotopy theory, and through homology and cohomology groups. -

Cavendish the Experimental Life

Cavendish The Experimental Life Revised Second Edition Max Planck Research Library for the History and Development of Knowledge Series Editors Ian T. Baldwin, Gerd Graßhoff, Jürgen Renn, Dagmar Schäfer, Robert Schlögl, Bernard F. Schutz Edition Open Access Development Team Lindy Divarci, Georg Pflanz, Klaus Thoden, Dirk Wintergrün. The Edition Open Access (EOA) platform was founded to bring together publi- cation initiatives seeking to disseminate the results of scholarly work in a format that combines traditional publications with the digital medium. It currently hosts the open-access publications of the “Max Planck Research Library for the History and Development of Knowledge” (MPRL) and “Edition Open Sources” (EOS). EOA is open to host other open access initiatives similar in conception and spirit, in accordance with the Berlin Declaration on Open Access to Knowledge in the sciences and humanities, which was launched by the Max Planck Society in 2003. By combining the advantages of traditional publications and the digital medium, the platform offers a new way of publishing research and of studying historical topics or current issues in relation to primary materials that are otherwise not easily available. The volumes are available both as printed books and as online open access publications. They are directed at scholars and students of various disciplines, and at a broader public interested in how science shapes our world. Cavendish The Experimental Life Revised Second Edition Christa Jungnickel and Russell McCormmach Studies 7 Studies 7 Communicated by Jed Z. Buchwald Editorial Team: Lindy Divarci, Georg Pflanz, Bendix Düker, Caroline Frank, Beatrice Hermann, Beatrice Hilke Image Processing: Digitization Group of the Max Planck Institute for the History of Science Cover Image: Chemical Laboratory. -

Maty's Biography of Abraham De Moivre, Translated

Statistical Science 2007, Vol. 22, No. 1, 109–136 DOI: 10.1214/088342306000000268 c Institute of Mathematical Statistics, 2007 Maty’s Biography of Abraham De Moivre, Translated, Annotated and Augmented David R. Bellhouse and Christian Genest Abstract. November 27, 2004, marked the 250th anniversary of the death of Abraham De Moivre, best known in statistical circles for his famous large-sample approximation to the binomial distribution, whose generalization is now referred to as the Central Limit Theorem. De Moivre was one of the great pioneers of classical probability the- ory. He also made seminal contributions in analytic geometry, complex analysis and the theory of annuities. The first biography of De Moivre, on which almost all subsequent ones have since relied, was written in French by Matthew Maty. It was published in 1755 in the Journal britannique. The authors provide here, for the first time, a complete translation into English of Maty’s biography of De Moivre. New mate- rial, much of it taken from modern sources, is given in footnotes, along with numerous annotations designed to provide additional clarity to Maty’s biography for contemporary readers. INTRODUCTION ´emigr´es that both of them are known to have fre- Matthew Maty (1718–1776) was born of Huguenot quented. In the weeks prior to De Moivre’s death, parentage in the city of Utrecht, in Holland. He stud- Maty began to interview him in order to write his ied medicine and philosophy at the University of biography. De Moivre died shortly after giving his Leiden before immigrating to England in 1740. Af- reminiscences up to the late 1680s and Maty com- ter a decade in London, he edited for six years the pleted the task using only his own knowledge of the Journal britannique, a French-language publication man and De Moivre’s published work. -

JBI 4.05 Newsletter

FOCUS ON JBI The Newsletter of JBI International • Spring 2007 JBI International JBI Reunites Senior and Volunteer After 40 Years (established in 1931 become a well-respected actor in the Moscow as the Jewish Braille Theater, but never saw her classmate again. Institute) provides the visually impaired, blind, Irina hurried upstairs to her apartment and physically handicapped returned with a photo album with a picture of and reading disabled of their graduating acting class. Sure enough, it was Victor! all backgrounds and ages with free books, Until that presentation, Irina did not realize how magazines and special valuable her acting skills would be for recording publications of Jewish materials for JBI’s Russian Collection . She and general interest in JBI volunteer Victor Persik reunites and reminisces with jumped at the opportunity to “do some acting Audio, Large Print and old friend Irina Gusso. again,” and we arranged for her to visit the JBI Braille. JBI, an Affiliated familiar name from the past touched off a studios. Little did Victor anticipate the Library of the United Amemory, and then a happy reunion, at JBI. wonderful surprise we had arranged for him States Library of It all began last December during a JBI Russian when he arrrived for his recording session. Congress, enables language outreach presentation at a senior There stood Irina, waiting to greet her old individuals with residence in Irvington, New Jersey, where 20 friend with arms wide open! diminished vision to seniors listened as Inna Suholutsky, our Russian understand and Liaison and Outreach Assistant, spoke about JBI JBI offers a wide variety of materials and participate in the cultural Library’s wealth of Russian Talking Books programs for the Russian community world- life of their communities. -

Fundamental Theorems in Mathematics

SOME FUNDAMENTAL THEOREMS IN MATHEMATICS OLIVER KNILL Abstract. An expository hitchhikers guide to some theorems in mathematics. Criteria for the current list of 243 theorems are whether the result can be formulated elegantly, whether it is beautiful or useful and whether it could serve as a guide [6] without leading to panic. The order is not a ranking but ordered along a time-line when things were writ- ten down. Since [556] stated “a mathematical theorem only becomes beautiful if presented as a crown jewel within a context" we try sometimes to give some context. Of course, any such list of theorems is a matter of personal preferences, taste and limitations. The num- ber of theorems is arbitrary, the initial obvious goal was 42 but that number got eventually surpassed as it is hard to stop, once started. As a compensation, there are 42 “tweetable" theorems with included proofs. More comments on the choice of the theorems is included in an epilogue. For literature on general mathematics, see [193, 189, 29, 235, 254, 619, 412, 138], for history [217, 625, 376, 73, 46, 208, 379, 365, 690, 113, 618, 79, 259, 341], for popular, beautiful or elegant things [12, 529, 201, 182, 17, 672, 673, 44, 204, 190, 245, 446, 616, 303, 201, 2, 127, 146, 128, 502, 261, 172]. For comprehensive overviews in large parts of math- ematics, [74, 165, 166, 51, 593] or predictions on developments [47]. For reflections about mathematics in general [145, 455, 45, 306, 439, 99, 561]. Encyclopedic source examples are [188, 705, 670, 102, 192, 152, 221, 191, 111, 635]. -

Optimal Control for Automotive Powertrain Applications

Universitat Politecnica` de Valencia` Departamento de Maquinas´ y Motores Termicos´ Optimal Control for Automotive Powertrain Applications PhD Dissertation Presented by Alberto Reig Advised by Dr. Benjam´ınPla Valencia, September 2017 PhD Dissertation Optimal Control for Automotive Powertrain Applications Presented by Alberto Reig Advised by Dr. Benjam´ınPla Examining committee President: Dr. Jos´eGalindo Lucas Secretary: Dr. Octavio Armas Vergel Vocal: Dr. Marcello Canova Valencia, September 2017 To the geniuses of the past, who built our future; to those names in the shades, bringing our knowledge. They not only supported this work but also the world we live in. If you can solve it, it is an exercise; otherwise it's a research problem. | Richard Bellman e Resumen El Control Optimo´ (CO) es esencialmente un problema matem´aticode b´us- queda de extremos, consistente en la definici´onde un criterio a minimizar (o maximizar), restricciones que deben satisfacerse y condiciones de contorno que afectan al sistema. La teor´ıade CO ofrece m´etodos para derivar una trayectoria de control que minimiza (o maximiza) ese criterio. Esta Tesis trata la aplicaci´ondel CO en automoci´on,y especialmente en el motor de combusti´oninterna. Las herramientas necesarias son un m´etodo de optimizaci´ony una representaci´onmatem´aticade la planta motriz. Para ello, se realiza un an´alisiscuantitativo de las ventajas e inconvenientes de los tres m´etodos de optimizaci´onexistentes en la literatura: programaci´ondin´amica, principio m´ınimode Pontryagin y m´etodos directos. Se desarrollan y describen los algoritmos para implementar estos m´etodos as´ıcomo un modelo de planta motriz, validado experimentalmente, que incluye la din´amicalongitudinal del veh´ıculo,modelos para el motor el´ectricoy las bater´ıas,y un modelo de motor de combusti´onde valores medios. -

From Abraham De Moivre to Johann Carl Friedrich Gauss

International Journal of Engineering Science Invention (IJESI) ISSN (Online): 2319 – 6734, ISSN (Print): 2319 – 6726 www.ijesi.org ||Volume 7 Issue 6 Ver V || June 2018 || PP 28-34 A Brief Historical Overview Of the Gaussian Curve: From Abraham De Moivre to Johann Carl Friedrich Gauss Edel Alexandre Silva Pontes1 1Department of Mathematics, Federal Institute of Alagoas, Brazil Abstract : If there were only one law of probability to be known, this would be the Gaussian distribution. Faced with this uneasiness, this article intends to discuss about this distribution associated with its graph called the Gaussian curve. Due to the scarcity of texts in the area and the great demand of students and researchers for more information about this distribution, this article aimed to present a material on the history of the Gaussian curve and its relations. In the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, there were several mathematicians who developed research on the curve, including Abraham de Moivre, Pierre Simon Laplace, Adrien-Marie Legendre, Francis Galton and Johann Carl Friedrich Gauss. Some researchers refer to the Gaussian curve as the "curve of nature itself" because of its versatility and inherent nature in almost everything we find. Virtually all probability distributions were somehow part or originated from the Gaussian distribution. We believe that the work described, the study of the Gaussian curve, its history and applications, is a valuable contribution to the students and researchers of the different areas of science, due to the lack of more detailed research on the subject. Keywords - History of Mathematics, Distribution of Probabilities, Gaussian Curve. ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- --------- Date of Submission: 09-06-2018 Date of acceptance: 25-06-2018 ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- ---------- I. -

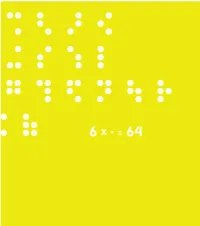

Nemeth Code Uses Some Parts of Textbook Format but Has Some Idiosyncrasies of Its Own

This book is a compilation of research, in “Understanding and Tracing the Problem faced by the Visually Impaired while doing Mathematics” as a Diploma project by Aarti Vashisht at the Srishti School of Art, Design and Technology, Bangalore. 6 DOTS 64 COMBINATIONS A Braille character is formed out of a combination of six dots. Including the blank space, sixty four combinations are possible using one or more of these six dots. CONTENTS Introduction 2 About Braille 32 Mathematics for the Visually Impaired 120 Learning Mathematics 168 C o n c l u s i o n 172 P e o p l e a n d P l a c e s 190 Acknowledgements INTRODUCTION This project tries to understand the nature of the problems that are faced by the visually impaired within the realm of mathematics. It is a summary of my understanding of the problems in this field that may be taken forward to guide those individuals who are concerned about this subject. My education in design has encouraged interest in this field. As a designer I have learnt to be aware of my community and its needs, to detect areas where design can reach out and assist, if not resolve, a problem. Thus began, my search, where I sought to grasp a fuller understanding of the situation by looking at the various mediums that would help better communication. During the project I realized that more often than not work happened in individual pockets which in turn would lead to regionalization of many ideas and opportunities. Data collection got repetitive, which would delay or sometimes even hinder the process. -

Mind Almost Divine’ Kevin C

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-66310-6 - From Newton to Hawking: A History of Cambridge University’s Lucasian Professors of Mathematics Edited by Kevin C. Knox and Richard Noakes Excerpt More information Introduction: ‘Mind almost divine’ Kevin C. Knox1 and Richard Noakes2 1Institute Archives, California Institute of Technology, Pasadena, CA, USA 2Department of History of Philosophy of Science, Cambridge, UK Whosoever to the utmost of his finite capacity would see truth as it has actually existed in the mind of God from all eternity, he must study Mathematics more than Metaphysics. Nicholas Saunderson, The Elements of Algebra1 As we enter the twenty-first century it might be possible to imag- ine the world without Cambridge University’s Lucasian professors of mathematics. It is, however, impossible to imagine our world with- out their profound discoveries and inventions. Unquestionably, the work of the Lucasian professors has ‘revolutionized’ the way we think about and engage with the world: Newton has given us universal grav- itation and the calculus, Charles Babbage is touted as the ‘father of the computer’, Paul Dirac is revered for knitting together quantum mechanics and special relativity and Stephen Hawking has provided us with startling new theories about the origin and fate of the uni- verse. Indeed, Newton, Babbage, Dirac and Hawking have made the Lucasian professorship the most famous academic chair in the world. While these Lucasian professors have been deified and placed in the pantheon of scientific immortals, eponymity testifies to the eminence of the chair’s other occupants. Accompanying ‘Newton’s laws of motion’, ‘Babbage’s principle’ of political economy, the ‘Dirac delta function’ and ‘Hawking radiation’, we have, among other things, From Newton to Hawking: A History of Cambridge University’s Lucasian Professors of Math- ematics, ed. -

Abraham De Moivre R Cosθ + Isinθ N = Rn Cosnθ + Isinnθ R Cosθ + Isinθ = R

Abraham de Moivre May 26, 1667 in Vitry-le-François, Champagne, France – November 27, 1754 in London, England) was a French mathematician famous for de Moivre's formula, which links complex numbers and trigonometry, and for his work on the normal distribution and probability theory. He was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society in 1697, and was a friend of Isaac Newton, Edmund Halley, and James Stirling. The social status of his family is unclear, but de Moivre's father, a surgeon, was able to send him to the Protestant academy at Sedan (1678-82). de Moivre studied logic at Saumur (1682-84), attended the Collège de Harcourt in Paris (1684), and studied privately with Jacques Ozanam (1684-85). It does not appear that De Moivre received a college degree. de Moivre was a Calvinist. He left France after the revocation of the Edict of Nantes (1685) and spent the remainder of his life in England. Throughout his life he remained poor. It is reported that he was a regular customer of Slaughter's Coffee House, St. Martin's Lane at Cranbourn Street, where he earned a little money from playing chess. He died in London and was buried at St Martin-in-the-Fields, although his body was later moved. De Moivre wrote a book on probability theory, entitled The Doctrine of Chances. It is said in all seriousness that De Moivre correctly predicted the day of his own death. Noting that he was sleeping 15 minutes longer each day, De Moivre surmised that he would die on the day he would sleep for 24 hours. -

Thomas Colby's Book Collection

12 Thomas Colby’s book collection Bill Hines Amongst the special collections held by Aberystwyth University Library are some 140 volumes from the library of Thomas Colby, one time Director of the Ordnance Survey, who was responsible for much of the initial survey work in Scotland and Ireland. Although the collection is fairly small, it nonetheless provides a fascinating insight into the working practices of the man, and also demonstrates the regard in which he was held by his contemporaries, many of them being eminent scientists and engineers of the day. Thomas Colby was born in 1784, the son of an officer in the Royal Marines. He was brought up by his aunts in Pembrokeshire and later attended the Royal Military Academy at Woolwich, becoming a Second Lieutenant in the Royal Engineers in December 1801.1 He came to the notice of Major William Mudge, the then Director of the Ordnance Survey, and was engaged on survey work in the south of England. In 1804 he suffered a bad accident from the bursting of a loaded pistol and lost his left hand. However, this did not affect his surveying activity and he became chief executive officer of the Survey in 1809 when Mudge was appointed as Lieutenant Governor at Woolwich. During the next decade he was responsible for extensive surveying work in Scotland and was also involved in troublesome collaboration with French colleagues after the end of the Napoleonic Wars, connecting up the meridian arcs of British and French surveys. Colby was made head of the Ordnance Survey in 1820, after the death of Mudge, and became a Fellow of the Royal Society in the same year.