Mind Almost Divine’ Kevin C

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mathematics in the Modern Age - the 18Th Century: Crossing Bridges Transcript

Mathematics in the modern age - The 18th century: Crossing bridges Transcript Date: Wednesday, 4 October 2006 - 12:00AM Location: Barnard's Inn Hall MATHEMATICS IN THE MODERN AGE - THE 18TH CENTURY: CROSSING BRIDGES Professor Robin Wilson Introduction After Isaac Newton had published his celebrated PrincipiaMathematicain 1687 – the book that explained gravitation and how the planets move – his life changed for ever, and in a way that would also affect the nature of British mathematics for the next 150 years or so. His book was highly praised in Britain, even though few people could understand it, and the reclusive Newton was now a public figure. After spending a year as an ineffective Member of Parliament for Cambridge University – apparently he spoke only once, and that was to ask an official to open a window – Newton became Warden, and later Master, of the Royal Mint, living in the Tower of London, supervising the minting of coins, and punishing counterfeiters. He had now left Cambridge for good. In 1703 Newton’s arch-rival Robert Hooke died, with repercussions for both Gresham College where he was Gresham Professor of Geometry, and the Royal Society which still held its meetings in Sir Thomas Gresham’s former house. The rebuilding of the Royal Exchange after the Great Fire of 1666 had been costly, and attendances at Gresham lectures were then sparse, so proposals were made to save money by rebuilding the College on a smaller scale. Parliament was petitioned for approval, with only Robert Hooke, now frail and the only professor resident in the College, holding out against the plans. -

Cavendish the Experimental Life

Cavendish The Experimental Life Revised Second Edition Max Planck Research Library for the History and Development of Knowledge Series Editors Ian T. Baldwin, Gerd Graßhoff, Jürgen Renn, Dagmar Schäfer, Robert Schlögl, Bernard F. Schutz Edition Open Access Development Team Lindy Divarci, Georg Pflanz, Klaus Thoden, Dirk Wintergrün. The Edition Open Access (EOA) platform was founded to bring together publi- cation initiatives seeking to disseminate the results of scholarly work in a format that combines traditional publications with the digital medium. It currently hosts the open-access publications of the “Max Planck Research Library for the History and Development of Knowledge” (MPRL) and “Edition Open Sources” (EOS). EOA is open to host other open access initiatives similar in conception and spirit, in accordance with the Berlin Declaration on Open Access to Knowledge in the sciences and humanities, which was launched by the Max Planck Society in 2003. By combining the advantages of traditional publications and the digital medium, the platform offers a new way of publishing research and of studying historical topics or current issues in relation to primary materials that are otherwise not easily available. The volumes are available both as printed books and as online open access publications. They are directed at scholars and students of various disciplines, and at a broader public interested in how science shapes our world. Cavendish The Experimental Life Revised Second Edition Christa Jungnickel and Russell McCormmach Studies 7 Studies 7 Communicated by Jed Z. Buchwald Editorial Team: Lindy Divarci, Georg Pflanz, Bendix Düker, Caroline Frank, Beatrice Hermann, Beatrice Hilke Image Processing: Digitization Group of the Max Planck Institute for the History of Science Cover Image: Chemical Laboratory. -

Thomas Colby's Book Collection

12 Thomas Colby’s book collection Bill Hines Amongst the special collections held by Aberystwyth University Library are some 140 volumes from the library of Thomas Colby, one time Director of the Ordnance Survey, who was responsible for much of the initial survey work in Scotland and Ireland. Although the collection is fairly small, it nonetheless provides a fascinating insight into the working practices of the man, and also demonstrates the regard in which he was held by his contemporaries, many of them being eminent scientists and engineers of the day. Thomas Colby was born in 1784, the son of an officer in the Royal Marines. He was brought up by his aunts in Pembrokeshire and later attended the Royal Military Academy at Woolwich, becoming a Second Lieutenant in the Royal Engineers in December 1801.1 He came to the notice of Major William Mudge, the then Director of the Ordnance Survey, and was engaged on survey work in the south of England. In 1804 he suffered a bad accident from the bursting of a loaded pistol and lost his left hand. However, this did not affect his surveying activity and he became chief executive officer of the Survey in 1809 when Mudge was appointed as Lieutenant Governor at Woolwich. During the next decade he was responsible for extensive surveying work in Scotland and was also involved in troublesome collaboration with French colleagues after the end of the Napoleonic Wars, connecting up the meridian arcs of British and French surveys. Colby was made head of the Ordnance Survey in 1820, after the death of Mudge, and became a Fellow of the Royal Society in the same year. -

Downloadedcambridge from Cambridge Companions Companions Online by ©IP Cambridge130.132.173.15 Universityon Wed Jun 05 Press, 15:31:00 2006 WEST 2013

Each volume of this series of companions to major philoso phers contains specially commissioned essays by an interna tional team of scholars, together with a substantial bibliog raphy, and will serve as a reference work for students and nonspecialists. One aim of the series is to dispel the intimi dation such readers often feel when faced with the work of a difficult and challenging thinker. John Locke, the founder of British empiricism, was also the seventeenth century's staunchest defender of reason in religion and politics. His Essay concerningHuman Under standing influenced eighteenth-century thought more pro foundly than any book save the Bible; his Two Tr eatises of Government helped inspire the American and French revo lutions; and much of his work is pertinent to current intel lectual and social problems. The essays in this volume pro vide a systematic survey of Locke's philosophy, informed by the most recent scholarship. They cover Locke's theory of ideas, his philosophies of body, mind, language, and religion, his theory of knowledge, his ethics, and his political philos ophy. There are also chapters on Locke's life and times and subsequent influence. New readers and nonspecialists will find this the most convenient and accessible guide to Locke currently avail able. Advanced students and specialists will find a conspec tus of recent developments in the interpretation of Locke's philosophy. DownloadedCambridge from Cambridge Companions Companions Online by ©IP Cambridge130.132.173.15 Universityon Wed Jun 05 Press, 15:31:00 2006 WEST 2013. http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/CCOL0521383714.013 Cambridge Companions Online © Cambridge University Press, 2013 THE CAMBRIDGE COMPANION TO LOCKE DownloadedCambridge from Cambridge Companions Companions Online by ©IP Cambridge130.132.173.15 Universityon Wed Jun 05 Press, 15:31:00 2006 WEST 2013. -

Blind Mathematicians

The World of Blind Mathematicians A visitor to the Paris apartment of the blind geome- able to resort to paper and pencil, Lawrence W. ter Bernard Morin finds much to see. On the wall Baggett, a blind mathematician at the University of in the hallway is a poster showing a computer- Colorado, remarked modestly, “Well, it’s hard to do generated picture, created by Morin’s student for anybody.” On the other hand, there seem to be François Apéry, of Boy’s surface, an immersion of differences in how blind mathematicians perceive the projective plane in three dimensions. The sur- their subject. Morin recalled that, when a sighted face plays a role in Morin’s most famous work, his colleague proofread Morin’s thesis, the colleague visualization of how to turn a sphere inside out. had to do a long calculation involving determi- Although he cannot see the poster, Morin is happy nants to check on a sign. The colleague asked Morin to point out details in the picture that the visitor how he had computed the sign. Morin said he must not miss. Back in the living room, Morin grabs replied: “I don’t know—by feeling the weight of the a chair, stands on it, and feels for a box on top of thing, by pondering it.” a set of shelves. He takes hold of the box and climbs off the chair safely—much to the relief of Blind Mathematicians in History the visitor. Inside the box are clay models that The history of mathematics includes a number of Morin made in the 1960s and 1970s to depict blind mathematicians. -

Contents More Information

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-66310-6 - From Newton to Hawking: A History of Cambridge University’s Lucasian Professors of Mathematics Edited by Kevin C. Knox and Richard Noakes Table of Contents More information Contents List of illustrations page vii List of contributors xiii Foreword xvii stephen hawking Preface xxi Timeline of the Lucasian professorship xxv Introduction: ‘Mind almost divine’ 1 kevin c. knox and richard noakes 1 Isaac Barrow and the foundation of the Lucasian professorship 45 mordechai feingold 2 ‘Very accomplished mathematician, philosopher, chemist’: Newton as Lucasian professor 69 rob iliffe 3 Making Newton easy: William Whiston in Cambridge and London 135 stephen d. snobelen and larry stewart 4 Sensible Newtonians: Nicholas Saunderson and John Colson 171 john gascoigne 5 The negative side of nothing: Edward Waring, Isaac Milner and Newtonian values 205 kevin c. knox © Cambridge University Press www.cambridge.org Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-66310-6 - From Newton to Hawking: A History of Cambridge University’s Lucasian Professors of Mathematics Edited by Kevin C. Knox and Richard Noakes Table of Contents More information vi contents 6 Paper and brass: the Lucasian professorship 1820–39 241 simon schaffer 7 Arbiters of Victorian science: George Gabriel Stokes and Joshua King 295 david b. wilson 8 ‘That universal æthereal plenum’: Joseph Larmor’s natural history of physics 343 andrew warwick 9 Paul Dirac: the purest soul in an atomic age 387 helge kragh 10 Is the end in sight for the Lucasian chair? Stephen Hawking as Millennium Professor 425 h´el`ene mialet Appendix The statutes of the Lucasian professorship: a translation 461 ian stewart Index 475 © Cambridge University Press www.cambridge.org. -

Introduction: 'Mind Almost Divine'

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-66310-6 - From Newton to Hawking: A History of Cambridge University’s Lucasian Professors of Mathematics Edited by Kevin C. Knox and Richard Noakes Excerpt More information Introduction: ‘Mind almost divine’ Kevin C. Knox1 and Richard Noakes2 1Institute Archives, California Institute of Technology, Pasadena, CA, USA 2Department of History of Philosophy of Science, Cambridge, UK Whosoever to the utmost of his finite capacity would see truth as it has actually existed in the mind of God from all eternity, he must study Mathematics more than Metaphysics. Nicholas Saunderson, The Elements of Algebra1 As we enter the twenty-first century it might be possible to imag- ine the world without Cambridge University’s Lucasian professors of mathematics. It is, however, impossible to imagine our world with- out their profound discoveries and inventions. Unquestionably, the work of the Lucasian professors has ‘revolutionized’ the way we think about and engage with the world: Newton has given us universal grav- itation and the calculus, Charles Babbage is touted as the ‘father of the computer’, Paul Dirac is revered for knitting together quantum mechanics and special relativity and Stephen Hawking has provided us with startling new theories about the origin and fate of the uni- verse. Indeed, Newton, Babbage, Dirac and Hawking have made the Lucasian professorship the most famous academic chair in the world. While these Lucasian professors have been deified and placed in the pantheon of scientific immortals, eponymity testifies to the eminence of the chair’s other occupants. Accompanying ‘Newton’s laws of motion’, ‘Babbage’s principle’ of political economy, the ‘Dirac delta function’ and ‘Hawking radiation’, we have, among other things, From Newton to Hawking: A History of Cambridge University’s Lucasian Professors of Math- ematics, ed. -

A Calendar of Mathematical Dates January

A CALENDAR OF MATHEMATICAL DATES V. Frederick Rickey Department of Mathematical Sciences United States Military Academy West Point, NY 10996-1786 USA Email: fred-rickey @ usma.edu JANUARY 1 January 4713 B.C. This is Julian day 1 and begins at noon Greenwich or Universal Time (U.T.). It provides a convenient way to keep track of the number of days between events. Noon, January 1, 1984, begins Julian Day 2,445,336. For the use of the Chinese remainder theorem in determining this date, see American Journal of Physics, 49(1981), 658{661. 46 B.C. The first day of the first year of the Julian calendar. It remained in effect until October 4, 1582. The previous year, \the last year of confusion," was the longest year on record|it contained 445 days. [Encyclopedia Brittanica, 13th edition, vol. 4, p. 990] 1618 La Salle's expedition reached the present site of Peoria, Illinois, birthplace of the author of this calendar. 1800 Cauchy's father was elected Secretary of the Senate in France. The young Cauchy used a corner of his father's office in Luxembourg Palace for his own desk. LaGrange and Laplace frequently stopped in on business and so took an interest in the boys mathematical talent. One day, in the presence of numerous dignitaries, Lagrange pointed to the young Cauchy and said \You see that little young man? Well! He will supplant all of us in so far as we are mathematicians." [E. T. Bell, Men of Mathematics, p. 274] 1801 Giuseppe Piazzi (1746{1826) discovered the first asteroid, Ceres, but lost it in the sun 41 days later, after only a few observations. -

“Dig Where You Stand” 5

Kristín Bjarnadóttir, Fulvia Furinghetti, Jenneke Krüger, Fulvia Furinghetti, Jenneke Krüger, Kristín Bjarnadóttir, Johan Prytz, Gert Schubring, Harm Jan Smid (Eds.) Kristín Bjarnadóttir, Fulvia Furinghetti, Jenneke Krüger, Johan Prytz, Gert Schubring, Harm Jan Smid (Eds.) The First International Conference on the History of Mathematics Education took place in Iceland in 2009. In the Proceedings, the editors expressed their expectation that the research on history of mathematics education would be sufficiently productive to warrant the continuation of this conference every two years. And indeed, participation has grown, from 35 participants and 18 presentations in 2009, to 65 participants and 40 presentations in 2017, at the Fifth Internatio- nal Conference on the History of Mathematics Education. “DIG WHERE YOU STAND” 5 The venue of the Fifth Conference was the historical University Hall of the University of Utrecht PROCEEDINGS OF THE FIFTH INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE in the Netherlands. The Descartes Centre and the Freudenthal Institute, both part of the Univer- ON THE HISTORY OF MATHEMATICS EDUCATION sity of Utrecht, and the Dutch Association of Mathematics Teachers sponsored the organisation SEPTEMBER 19-22, 2017, AT UTRECHT UNIVERSITY, THE NETHERLANDS and the Proceedings of the conference. The Local Committee, consisting of Heleen van der Ree, Harm Jan Smid, Jan van Guichelaar and Jenneke Krüger, organized the conference in an excel- lent manner. The final editing of the Proceedings was in the capable hands of Nathalie Kuijpers. Previous international conferences on the history of mathematics education: 2009 Garðabær (Iceland) 2011 Lisboa (Portugal) 2013 Uppsala (Sweden) 2015 Torino (Italy) The Sixth International Conference on the History of Mathematics Education will be held in Marseille (France) in September 2019. -

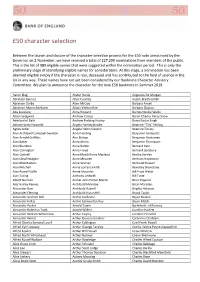

50 Character Selection

£50 character selection Between the launch and closure of the character selection process for the £50 note announced by the Governor on 2 November, we have received a total of 227,299 nominations from members of the public. This is the list of 989 eligible names that were suggested within the nomination period. This is only the preliminary stage of identifying eligible names for consideration: At this stage, a nomination has been deemed eligible simply if the character is real, deceased and has contributed to the field of science in the UK in any way. These names have not yet been considered by our Banknote Character Advisory Committee. We plan to announce the character for the new £50 banknote in Summer 2019. Aaron Klug Alister Hardy Augustus De Morgan Abraham Bennet Allen Coombs Austin Bradford Hill Abraham Darby Allen McClay Barbara Ansell Abraham Manie Adelstein Alliott Verdon Roe Barbara Clayton Ada Lovelace Alma Howard Barnes Neville Wallis Adam Sedgwick Andrew Crosse Baron Charles Percy Snow Aderlard of Bath Andrew Fielding Huxley Bawa Kartar Singh Adrian Hardy Haworth Angela Hartley Brodie Beatrice "Tilly" Shilling Agnes Arber Angela Helen Clayton Beatrice Tinsley Alan Archibald Campbell‐Swinton Anita Harding Benjamin Gompertz Alan Arnold Griffiths Ann Bishop Benjamin Huntsman Alan Baker Anna Atkins Benjamin Thompson Alan Blumlein Anna Bidder Bernard Katz Alan Carrington Anna Freud Bernard Spilsbury Alan Cottrell Anna MacGillivray Macleod Bertha Swirles Alan Lloyd Hodgkin Anne McLaren Bertram Hopkinson Alan MacMasters Anne Warner -

CHRIST's COLLEGE CAMBRIDGE Christs.Cam.Ac.Uk

CHRIST'S COLLEGE CAMBRIDGE CATALOGUE OF FELLOWS’ PAPERS Last updated 31 March 2020 by John Wagstaff 1 CONTENTS Box Number 1. Fragments found during the restoration of the Master's Lodge + Bible Box 2. Fragments and photocopies of music 3. Letter from Robert Hardy to his son Samuel 4. Photocopies of the title pages and dedications of ‘A Digest or Harmonie...’ W. Perkins 5. Facsimile of the handwriting of Lady Margaret (framed in Bodley Library) 6. MSS of ‘The Foundation of the University of Cambridge’ 1620 John Scott 7. Extract from the College “Admission Book” showing the entry of John Milton facsimile) 8. Milton autographs: three original documents 9. Letter from Mrs. R. Gurney 10. Letter from Henry Ellis to Thomas G. Cullum 11. Facsimile of the MS of Milton's Minor Poems 12. Thomas Hollis & Milton 13. Notes on Early Editions of Paradise Lost by C. Lofft 14. Copy of a letter from W.W. Torrington 15. Milton Tercentenary: Visitors' Book 16. Milton Tercentenary: miscellaneous material, (including "scrapbook") 17. Milton Tercentenary: miscellaneous documents 18. MS of a 17th century sermon by Alsop? 19. Receipt for a contribution by Sir Justinian Isham signed by M. Honywood 20. MS of ‘Some Account of Dr. More's Works’ by Richard Ward 21. Letters addressed to Dr. More and Dr. Ward (inter al.) 22. Historical tracts: 17th. century Italian MS 23. List of MSS in an unidentified hand 24. Three letters from Dr. John Covel to John Roades 25. MS copy of works by Prof. Nicholas Saunderson [in MSS safe] + article on N.S. -

'Seeing Through Touch': the Material World of Visually Impaired Children1

‘Seeing through touch’: the material world of visually impaired children1 “Vendo através do toque”: o mundo material das crianças com deficiência visual Ian Grosvenor2 Natasha Macnab2 ABSTRACT This article examines the changing material world of the visually impaired child and the ways in which this has been viewed and understood by scholars, philosophers, educators and other commentators over time. It describes and analyses tactile encounters as they have been planned for by educators, museum curators and others, from the Age of the Enlightenment until the present day. It takes as its starting point a recent blog that appeared online in 2011, which posted images from handling sessions for the visually impaired child, organized by John Alfred Charlton Deas from Sunderland Museum, England, between 1913-1926. It traces the provenance and development of ideas around ‘seeing through touch’, from the embossed books and maps and the printing machines for systems such as Braille in the nineteenth century to the theoretical and pedagogical developments which began to occur at the start of the twentieth century. Keywords: culture material; museum; blindness; visually impaired children. RESUMO Este artigo analisa as mudanças no mundo material da criança com defi ciência visual e as formas como ela foi vista e entendida ao longo do tempo por estudiosos, filósofos, educadores e outros comentaristas. Ele descreve e analisa como os encontros táteis, desde o Iluminismo até os dias de hoje 1 The authors would like to thank Tyne and Wear Archives and Museum and for permission to reproduce the Sunderland Museum photographs and the Museum Association for providing information on J.A.