Learning to Live with Crime

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Literary Lady by Ernest J. Abeytia a Creative Project

Case 99: The Literary Lady by Ernest J. Abeytia A creative project submitted to Sonoma State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS in English Committee Members: Prof. Stefan Kiesbye Dr. Scott Miller 04 May 2018 i Copyright 2018 By Ernest J. Abeytia ii Authorization for Reproduction of Master's Project Permission to reproduce this project in part or in entirety must be obtained from me. 04 May 2018 Ernest J. Abeytia iii Case 99: The Literary Lady By Ernest J. Abeytia ABSTRACT This is a crime fiction novel. It is a confluence of the styles, settings, plot lines, and character development of such luminaries of detective storytelling as Raymond Chandler, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, and Elmore Leonard, but it is not a hard copy or “cover” of anything they wrote. Bob Derby is a homicide detective in the Gardena, California police department. Gardena is one of 88 cities or towns in the County of Los Angeles. He has made an arrest in, or “cleared,” 98 of 101 homicide cases as the story begins, but he has never actually solved any of them. Somebody else always beats him to it and he then applies the police procedure that closes the case. The murder of Emma Williams is to be no different. iv Table of Contents Critical Introduction ........................................................................................................ vi Bibliography ................................................................................................................... xix Case 99: The Literary Lady ................................................................................................1 v Case 99: The Literary Lady By Ernest J. Abeytia A Critical Introduction The most famous detective in history is a fictional character. When Sir Arthur Conan Doyle sent Sherlock Holmes off a cliff overlooking the Reichenbach Falls in “The Final Problem” (1893), more than 20,000 readers cancelled their subscriptions to The Strand magazine, nearly putting the publication under. -

A Review of FBI Security Programs, March 2002

U.S. Department of Justice A Review of FBI Security Programs Commission for Review of FBI Security Programs March 2002 Commission for the Review of FBI Security Programs United States Department of Justice 950 Pennsylvania Avenue, NW, Room 1521 Washington, DC 20530 (202) 616-1327 Main (202) 616-3591 Facsimile March 31, 2002 The Honorable John Ashcroft Attorney General United States Department of Justice 950 Pennsylvania Avenue, N.W. Washington, D.C. 20530 Dear Mr. Attorney General: In March 2001, you asked me to lead a Commission to study security programs within the Federal Bureau of Investigation. Your request came at the urging of FBI Director Louis Freeh, who had concluded that an outside review was critical in light of the then recently discovered espionage by a senior Bureau official. In discharging my duties, I turned to six distinguished citizens as fellow Commissioners and to a staff of highly qualified professionals. I want to acknowledge the diligence with which my colleagues pursued the complex matters within our mandate. The Commission took its responsibilities seriously. It was meticulous in its investigation, vigorous in its discussions, candid in sharing views, and unanimous in its recommendations. When I agreed to chair the Commission, you promised the full cooperation and support of the Department of Justice and the FBI. That promise has been fulfilled. I would like to thank the Department’s Security and Emergency Planning Staff for the expert help they gave us, and I especially commend the cooperation of Director Mueller and FBI personnel at every level, who have all been chastened by treachery from within. -

Forgiving & Forgetting in American Justice

Forgiving and Forgetting in American Justice A 50-State Guide to Expungement and Restoration of Rights October 2017 COLLATERAL CONSEQUENCES RESOURCE CENTER The Collateral Consequences Resource Center is a non-profit organization established in 2014 to promote public discussion of the collateral consequences of conviction, the legal restrictions and social stigma that burden people with a criminal record long after their court-imposed sentence has been served. The resources available on the Center website are aimed primarily at lawyers and other criminal justice practitioners, scholars and researchers, but they should also be useful to policymakers and those most directly affected by the consequences of conviction. We welcome information about relevant current developments, including judicial decisions and new legislation, as well as proposals for blog posts on topics related to collateral consequences and criminal records. In addition, Center board members and staff are available to advise on law reform and practice issues. For more information, visit the CCRC at http://ccresourcecenter.org. This report was prepared by staff of the Collateral Consequences Resource Center, and is based on research compiled for the Restoration of Rights Project, a CCRC project launched in August 2017 in partnership with the National Association of Criminal Defense Lawyers, the National Legal Aid & Defender Association, and the National HIRE Network. The Restoration of Rights Project is an online resource containing detailed state-by-state analyses of the law and practice in each U.S. jurisdiction relating to restoration of rights and status following arrest or conviction. Jurisdictional “profiles” cover areas such as loss and restoration of civil rights and firearms rights, judicial and executive mechanisms for avoiding or mitigating collateral consequences, and provisions addressing non- discrimination in employment and licensing. -

Ridley Scott Is Re-Engineering the Iconic Xenomorph for an Alien Prequel/Sequel That’S Taking the Sci-Fi Horror Series Back to Its Fright-Filled Roots

ON SET 72 Nearly four decades after bursting onto the scene, Ridley Scott is re-engineering the iconic xenomorph for an Alien prequel/sequel that’s taking the sci-fi horror series back to its fright-filled roots. Total Film takes an express elevator to hell – aka the Sydney set of ALIEN: COVENANT – and comes face to face with a perfect organism. WORDS JORDan FARLEY TOTAL FILM | JULy 2017 ALIEN: COVENANT 73 JULy 2017 | TOTAL FILM MAKING OF idley Scott remembers Shepperton Studios like he’s just woken up from hypersleep. He remembers making movie history with Alien in 1979. Above all, he remembers his idle hands. How his own digits doubled for the finger-like legs of the facehugger twitching inside the egg. How he drew the film’s storyboards while studio suits ummed and ahhed over the budget. How he would improvise and improve set-ups until seconds before shooting, all because sitting around 74 – a common experience on film sets – would drive him “crazy”. If Ridley Scott’s own Alien memories are inextricably associated 78-year-old filmmaker’s mind for half nightmare and bland crossover franchise with idle hands, it’s only right that the his life. “Did it come about by accident… fodder. Scott famously returned to xenomorph itself, as revealed in Alien: or was it by design?” the series he launched in 2012 with Covenant, should be the product of a One thing’s for certain: intelligent Prometheus, an ambitious but flawed devil’s workshop. “Why on earth would design has rarely figured into the ad hoc prequel about the origins of humanity anyone make such a creature, and to evolution of the Alien series. -

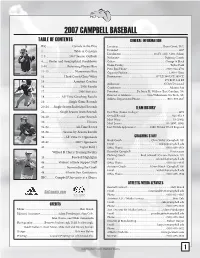

2007 CAMPBELL BASEBALL TABLE of CONTENTS General Information IFC

2007 CAMPBELL BASEBALL TABLE OF CONTENTS GENERAL INFORMATION IFC ..................................Camels in the Pros Location: .................................................................. Buies Creek, N.C. 1 ......................................... Table of Contents Founded: ......................................................................................... 1887 Enrollment:................................................10,471 (All), 6,982 (Main) 2-3 ...............................2007 Season Outlook Nickname: ..................................................................Fighting Camels 4 ....... Roster and Geographical Breakdown Colors: ..........................................................................Orange & Black 5-10 ..........................Returning Players Bios Home Facility: ....................................................................Taylor Field Press Box Phone: .........................................................(910) 814-4781 11-13 ...................................Newcomers Bios Capacity/Surface: .............................................................1,000 / Grass 14 .......................... Head Coach Chris Wiley Dimensions: .................................................337 LF, 368 LCF, 395 CF, 15 ...................................... Assistant Coaches 375 RCF, 328 RF Affiliation: .................................................................NCAA Division I 16 ................................................2006 Results Conference: .......................................................................Atlantic -

Notes Toward a History of American Justice

Buffalo Law Review Volume 24 Number 1 Article 5 10-1-1974 Notes Toward a History of American Justice Lawrence M. Friedman Stanford University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.buffalo.edu/buffalolawreview Part of the Comparative and Foreign Law Commons, Criminal Law Commons, and the Legal History Commons Recommended Citation Lawrence M. Friedman, Notes Toward a History of American Justice, 24 Buff. L. Rev. 111 (1974). Available at: https://digitalcommons.law.buffalo.edu/buffalolawreview/vol24/iss1/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at Digital Commons @ University at Buffalo School of Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Buffalo Law Review by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ University at Buffalo School of Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. NOTES TOWARD A HISTORY OF AMERICAN JUSTICE* LAWRRENCE M. FRIEDMAN** n Kent County, Delaware, in 1703, Adam Latham, a laborer, and Joan Mills, wife of a laborer named Andrew Mills, were brought before the county court. The grand jury presented Joan Mills for adultery. She pleaded guilty to the charge. For punishment, the court ordered her to be publicly whipped-21 lashes on her bare back, well applied; and she was also sentenced to prison, at hard labor, for one year. Adam Latham was convicted of fornication. He was sentenced to receive 20 lashes on his bare back, well laid on, in full public view. He was also accused of stealing Isaac Freeland's dark brown gelding, worth 2 pounds 10 shillings. Adam pleaded guilty; for this crime he was sentenced to another four lashes, and was further required to pay for the gelding. -

The Department of Justice and the Limits of the New Deal State, 1933-1945

THE DEPARTMENT OF JUSTICE AND THE LIMITS OF THE NEW DEAL STATE, 1933-1945 A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY AND THE COMMITTEE ON GRADUATE STUDIES OF STANFORD UNIVERSITY IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Maria Ponomarenko December 2010 © 2011 by Maria Ponomarenko. All Rights Reserved. Re-distributed by Stanford University under license with the author. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution- Noncommercial 3.0 United States License. http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/us/ This dissertation is online at: http://purl.stanford.edu/ms252by4094 ii I certify that I have read this dissertation and that, in my opinion, it is fully adequate in scope and quality as a dissertation for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. David Kennedy, Primary Adviser I certify that I have read this dissertation and that, in my opinion, it is fully adequate in scope and quality as a dissertation for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Richard White, Co-Adviser I certify that I have read this dissertation and that, in my opinion, it is fully adequate in scope and quality as a dissertation for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Mariano-Florentino Cuellar Approved for the Stanford University Committee on Graduate Studies. Patricia J. Gumport, Vice Provost Graduate Education This signature page was generated electronically upon submission of this dissertation in electronic format. An original signed hard copy of the signature page is on file in University Archives. iii Acknowledgements My principal thanks go to my adviser, David M. -

PERFECTION, WRETCHED, NORMAL, and NOWHERE: a REGIONAL GEOGRAPHY of AMERICAN TELEVISION SETTINGS by G. Scott Campbell Submitted T

PERFECTION, WRETCHED, NORMAL, AND NOWHERE: A REGIONAL GEOGRAPHY OF AMERICAN TELEVISION SETTINGS BY G. Scott Campbell Submitted to the graduate degree program in Geography and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. ______________________________ Chairperson Committee members* _____________________________* _____________________________* _____________________________* _____________________________* Date defended ___________________ The Dissertation Committee for G. Scott Campbell certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: PERFECTION, WRETCHED, NORMAL, AND NOWHERE: A REGIONAL GEOGRAPHY OF AMERICAN TELEVISION SETTINGS Committee: Chairperson* Date approved: ii ABSTRACT Drawing inspiration from numerous place image studies in geography and other social sciences, this dissertation examines the senses of place and regional identity shaped by more than seven hundred American television series that aired from 1947 to 2007. Each state‘s relative share of these programs is described. The geographic themes, patterns, and images from these programs are analyzed, with an emphasis on identity in five American regions: the Mid-Atlantic, New England, the Midwest, the South, and the West. The dissertation concludes with a comparison of television‘s senses of place to those described in previous studies of regional identity. iii For Sue iv CONTENTS List of Tables vi Acknowledgments vii 1. Introduction 1 2. The Mid-Atlantic 28 3. New England 137 4. The Midwest, Part 1: The Great Lakes States 226 5. The Midwest, Part 2: The Trans-Mississippi Midwest 378 6. The South 450 7. The West 527 8. Conclusion 629 Bibliography 664 v LIST OF TABLES 1. Television and Population Shares 25 2. -

From Academy Award® Winning Executive Producers Martin Scorsese*, Brian Grazer** & Ron Howard***, and Certified Fresh On

Social Messaging: Follow @r0bbier0berts0n on his musical journey with an iconic American band in #OnceWereBrothers: #RobbieRobertson & The Band. Featuring @ScorsesMartin, @BobDylan, @Springsteen & more, @TheBandFilm arrives on #Bluray, #DVD & #Digital on 5/26. Available now for Digital rental. FROM ACADEMY AWARD® WINNING EXECUTIVE PRODUCERS MARTIN SCORSESE*, BRIAN GRAZER** & RON HOWARD***, AND CERTIFIED FRESH ON ROTTEN TOMATOES® Director Daniel Roher’s Documentary Takes Center Stage As Robbie Robertson Recalls His Personal Journey With One of the Most Enduring Groups in the History of Popular Music, Available Now for Digital Rental and Arriving on Blu-Ray™, DVD and Digital on May 26 from Magnolia Home Entertainment “A gripping saga of triumph and tribulation. Captures the story with vigorous urgency and passion that fits the music itself.” - USA Today “Has the power to transport you.” - The Wrap LOS ANGELES - Inspired by Robbie Robertson’s 2017 bestselling memoir “Testimony,” Once Were Brothers: Robbie Robertson and The Band “deeply dissects The Band’s magic and dysfunction” (Rolling Stone) and arrives on Blu-ray, DVD and Digital on May 26 from Magnolia Home Entertainment. Presenting a backstage view of The Band’s inner workings and offering audiences an unseen look at their impact on the music industry, the documentary chronicles Robbie’s introduction to music and the group’s revolutionary collaboration with Bob Dylan, to their final tour as one of the most influential groups of their era. * 2007 - Best Achievement in Directing, Hugo ** 2002 - Best Picture, A Beautiful Mind *** 2002 - Best Director, A Beautiful Mind 1 From director Daniel Roher (Survivors Rowe), Once Were Brothers unravels the compelling story of the popular rock ‘n’ roll band alongside Robbie and those closest to The Band, including Martin Scorsese, Bruce Springsteen, Eric Clapton, Van Morrison, Taj Mahal, Ronnie Hawkins and more. -

Crime, Class, and Labour in David Simon's Baltimore

"From here to the rest of the world": Crime, class, and labour in David Simon's Baltimore. Sheamus Sweeney B.A. (Hons), M.A. (Hons) This thesis is submitted to Dublin City University for the award of Ph.D in the Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences. August 2013 School of Communications Supervisors: Prof. Helena Sheehan and Dr. Pat Brereton I hereby certify that this material, which I now submit for assessment on the programme of study leading to the award of Ph.D is entirely my own work, and that I have exercised reasonable care to ensure that the work is original, and does not to the best of my knowledge breach any law of copyright, and has not been taken from the work of others save and to the extent that such work has been cited and acknowledged within the text of my work. Signed: ___________________________________ (Candidate) ID No.: _55139426____ Date: _______________ TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction 1 Literature review and methodology 17 Chapter One: Stand around and watch: David Simon and the 42 "cop shop" narrative. Chapter Two: "Let the roughness show": From death on the 64 streets to a half-life on screen. Chapter Three: "Don't give the viewer the satisfaction": 86 Investigating the social order in Homicide. Chapter Four: Wasteland of the free: Images of labour in the 122 alternative economy. Chapter Five: The Wire: Introducing the other America. 157 Chapter Six: Baltimore Utopia? The limits of reform in the 186 war on labour and the war on drugs. Chapter Seven: There is no alternative: Unencumbered capitalism 216 and the war on drugs. -

Completeandleft

MEN WOMEN 1. JA Jason Aldean=American singer=188,534=33 Julia Alexandratou=Model, singer and actress=129,945=69 Jin Akanishi=Singer-songwriter, actor, voice actor, Julie Anne+San+Jose=Filipino actress and radio host=31,926=197 singer=67,087=129 John Abraham=Film actor=118,346=54 Julie Andrews=Actress, singer, author=55,954=162 Jensen Ackles=American actor=453,578=10 Julie Adams=American actress=54,598=166 Jonas Armstrong=Irish, Actor=20,732=288 Jenny Agutter=British film and television actress=72,810=122 COMPLETEandLEFT Jessica Alba=actress=893,599=3 JA,Jack Anderson Jaimie Alexander=Actress=59,371=151 JA,James Agee June Allyson=Actress=28,006=290 JA,James Arness Jennifer Aniston=American actress=1,005,243=2 JA,Jane Austen Julia Ann=American pornographic actress=47,874=184 JA,Jean Arthur Judy Ann+Santos=Filipino, Actress=39,619=212 JA,Jennifer Aniston Jean Arthur=Actress=45,356=192 JA,Jessica Alba JA,Joan Van Ark Jane Asher=Actress, author=53,663=168 …….. JA,Joan of Arc José González JA,John Adams Janelle Monáe JA,John Amos Joseph Arthur JA,John Astin James Arthur JA,John James Audubon Jann Arden JA,John Quincy Adams Jessica Andrews JA,Jon Anderson John Anderson JA,Julie Andrews Jefferson Airplane JA,June Allyson Jane's Addiction Jacob ,Abbott ,Author ,Franconia Stories Jim ,Abbott ,Baseball ,One-handed MLB pitcher John ,Abbott ,Actor ,The Woman in White John ,Abbott ,Head of State ,Prime Minister of Canada, 1891-93 James ,Abdnor ,Politician ,US Senator from South Dakota, 1981-87 John ,Abizaid ,Military ,C-in-C, US Central Command, 2003- -

Language and Jury Decision-Making in Texas Death Penalty Trials

The author(s) shown below used Federal funds provided by the U.S. Department of Justice and prepared the following final report: Document Title: Doing Death in Texas: Language and Jury Decision-Making in Texas Death Penalty Trials Author: Robin Helene Conley Document No.: 236354 Date Received: November 2011 Award Number: 2009-IJ-CX-0005 This report has not been published by the U.S. Department of Justice. To provide better customer service, NCJRS has made this Federally- funded grant final report available electronically in addition to traditional paper copies. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice. This document is a research report submitted to the U.S. Department of Justice. This report has not been published by the Department. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice. UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Doing Death in Texas: Language and Jury Decision-Making in Texas Death Penalty Trials A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Anthropology by Robin Helene Conley 2011 This document is a research report submitted to the U.S. Department of Justice. This report has not been published by the Department. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S.