Waste Reduction Inquiry

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

LABOUR and TECHNOLOGY in the CAR INDUSTRY. Ford Strategies in Britain and Brazil

LABOUR AND TECHNOLOGY IN THE CAR INDUSTRY. Ford strategies in Britain and Brazil Elizabeth Bortolaia Silva Thesis submitted for the Degree of PhD, Imperial College of Science and Technology University of London May 1988 LABOUR AND TECHNOLOGY IN THE CAR INDUSTRY Ford strategies in Britain and Brazil ABSTRACT This thesis looks at aspects of recent changes in international competition in the car industry. It examines the implications of the changes for the relationship between technology and work and it considers how strategies of multinational corporations interact with different national contexts. It is based on a case-study of the Ford Motor Company in its two largest factories in Britain and Brazil, Dagenham and São Bernardo. Chapter 1 describes existing theoretical approaches to comparative studies of technology and work, criticizes technological and cultural determinist approaches and argues for a method that draws on a 'historical regulation' approach. Chapters 2, 3 and 4 describe the long-term background and recent shifts in the pattern of international competition in the motor industry. In particular they look at important shifts in the late 1970s and 1980s and at Ford's changes in management structure and product strategy designed to meet these challenges. Chapter 5 considers recent debates on international productivity comparisons and presents a fieldwork-based comparison of the production process at Dagenham and São Bernardo. The description shows the importance of issues other than technology in determining the flexibility and quality of production. In different national contexts, 2 different mixes of technology and labour can produce comparable results. Chapters 6, 7 and 8 look at the national and local contexts of industrial relations in the two countries to throw light on the different patterns of change observed in the factories. -

THE DECEMBER SALE Collectors’ Motor Cars, Motorcycles and Automobilia Thursday 10 December 2015 RAF Museum, London

THE DECEMBER SALE Collectors’ Motor Cars, Motorcycles and Automobilia Thursday 10 December 2015 RAF Museum, London THE DECEMBER SALE Collectors' Motor Cars, Motorcycles and Automobilia Thursday 10 December 2015 RAF Museum, London VIEWING Please note that bids should be ENQUIRIES CUSTOMER SERVICES submitted no later than 16.00 Wednesday 9 December Motor Cars Monday to Friday 08:30 - 18:00 on Wednesday 9 December. 10.00 - 17.00 +44 (0) 20 7468 5801 +44 (0) 20 7447 7447 Thereafter bids should be sent Thursday 10 December +44 (0) 20 7468 5802 fax directly to the Bonhams office at from 9.00 [email protected] Please see page 2 for bidder the sale venue. information including after-sale +44 (0) 8700 270 089 fax or SALE TIMES Motorcycles collection and shipment [email protected] Automobilia 11.00 +44 (0) 20 8963 2817 Motorcycles 13.00 [email protected] Please see back of catalogue We regret that we are unable to Motor Cars 14.00 for important notice to bidders accept telephone bids for lots with Automobilia a low estimate below £500. +44 (0) 8700 273 618 SALE NUMBER Absentee bids will be accepted. ILLUSTRATIONS +44 (0) 8700 273 625 fax 22705 New bidders must also provide Front cover: [email protected] proof of identity when submitting Lot 351 CATALOGUE bids. Failure to do so may result Back cover: in your bids not being processed. ENQUIRIES ON VIEW Lots 303, 304, 305, 306 £30.00 + p&p AND SALE DAYS (admits two) +44 (0) 8700 270 090 Live online bidding is IMPORTANT INFORMATION available for this sale +44 (0) 8700 270 089 fax BIDS The United States Government Please email [email protected] has banned the import of ivory +44 (0) 20 7447 7447 with “Live bidding” in the subject into the USA. -

Motor Industry Facts 2015 Environment

UK AUTOMOTIVE AT A GLANCE UK AUTOMOTIVE INDUSTRY: PROFILE MANUFACTURING REGISTRATIONS THE SOCIETY OF MOTOR VEHICLES ON MANUFACTURERS AND TRADERS THE ROAD MOTOR INDUSTRY FACTS 2015 ENVIRONMENT SAFETY AND SECURITY CONNECTED CARS UK AUTOMOTIVE WHAT IS SMMT? AT A GLANCE UK AUTOMOTIVE The Society of Motor Manufacturers and Traders (SMMT) is one of the largest INDUSTRY: and most influential trade associations operating in the UK. Its resources, PROFILE reputation and unrivalled automotive data place it at the heart of the UK automotive industry. It undertakes a variety of activities to support and represent the interests of the industry and has a long history MANUFACTURING of achievement. Working closely with member companies, SMMT acts as the voice of the UK motor industry, supporting and promoting its interests, at home and abroad, REGISTRATIONS to government, stakeholders and the media. VEHICLES ON SMMT represents over 600 automotive companies in the UK, providing them THE ROAD with a forum to voice their views on issues affecting the automotive sector, helping to guide strategies and build positive relationships with government and regulatory authorities. ENVIRONMENT To find out how to join SMMT and for more information, visit www.smmt.co.uk/memberservices SAFETY AND or e-mail [email protected]. SECURITY CONNECTED www.smmt.co.uk 02 CARS UK AUTOMOTIVE CONTENTS AT A GLANCE UK AUTOMOTIVE INDUSTRY: UK AUTOMOTIVE AT A GLANCE ...................................4-5 REGISTRATIONS ............................................................16 -

Chief Medical Officer, Ford of Britain. an Exciting Opportunity Has Arisen

Chief Medical Officer, Ford of Britain. An exciting opportunity has arisen for an experienced Occupational Physician to join Ford Motor Company. You will provide health leadership, representing the health function at the highest level in one of the country’s leading automotive and mobility companies. You will lead on health strategy, manage the occupational health service and work with the wider global Ford community on health initiatives. This is a great opportunity to have a major impact in a large company experiencing rapid change. This is your chance to go further with Ford! Ford of Britain provides occupational health services to all employees based in the UK, via an outsourced provider. The role will be based at the Dunton Technical Centre, Essex, but will require travel to other operational sites including Dagenham, Bridgend (S Wales), Daventry and Liverpool. Job Role Responsibilities Professional • Health leadership across the organisation. • Interface with key stakeholders to deliver best practice occupational health services across the business. • Develop health strategy for the Company within UK, including wellbeing initiatives. • Ratification and review of all ill health retirement recommendations. • Regular process audit of the service at all sites. Management • Represent the health function at national level meetings with other key Company stakeholders such as Trades Unions and senior management. • Management of an outsourced occupational health service in liaison with the outsourced company’s own management team, to set KPIs. • Oversight of an outsourced on-site physiotherapy and rehabilitation service with reference to the provider’s own management, including regular review of KPIs. • Work with other medical staff within Ford of Europe and the wider global Ford health community on health initiatives and metrics. -

Motor Industry Facts

MOTOR INDUSTRY FACTS - 2006 www.smmt.co.uk Need Data? From production and first registration, to used vehicle sales and those on the road, SMMT Data Services is the primary source of data on the motor industry. Call us to find out more on 020 7235 7000 or go to www.smmt.co.uk/dataservices CONTENTS MOTOR INDUSTRY FACTS - 2006 1 NEW CAR REGISTRATIONS USED CAR SALES Annual totals and 2005 best sellers 2 Top 10 and annual totals 21 European 3 Diesel 4-5 PRODUCTION Fleet and business 6 Car production annual totals 22 Segment totals and market share 7 CV production annual totals 23 Best sellers by segment 8-10 Key manufacturing sites 24-25 Regional 11-12 UK top five producers 26 Engine production 27 COMMERCIAL VEHICLE REGISTRATIONS KEY ISSUES Annual totals 13 New car CO2 improvements 28 Segment totals 14 Taxation – VED bands 29 Bus and coach – registrations and production 15 Taxation – fuel duty 30 Motorhomes – annual registrations and UK manufacturing costs 31 best sellers 16 Road safety casualties 32 Vehicle security 33 VEHICLES IN USE Cars on the road 17 SMMT BUSINESSES Age of cars on the road 18 Industry Forum 34 Colours of cars on the road 19 Automotive Academy 34 Satellite navigation and in-car entertainment 20 Foresight Vehicle 34 SMMT information 35 www.smmt.co.uk NEW CAR REGISTRATIONS Annual UK totals and 2005 bestsellers 2 Ten year annual new car registration totals Top 10 registered models in 2005 Rank Make Model Range Volume 1 FORD FOCUS 145,010 2,563,631 2,579,050 2,567,269 2,458,769 2,439,717 2 VAUXHALL ASTRA 108,461 3 VAUXHALL -

Auto 04 Temp.Qxd

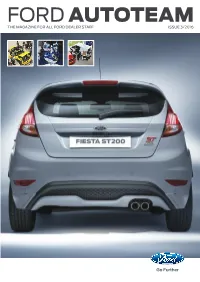

FORD AUTOTEAM THE MAGAZINE FOR ALL FORD DEALER STAFF ISSUE 3/2016 EDITORIAL Changing Times It’s all change for the management team at the Henry Ford Academy. Stuart Harris has moved on to a new position within Ford of Europe and, as I move into his role, I hope to continue with his goal of driving up training standards. Also joining the team is new Academy Principle, Kevin Perks, who brings with him a lifetime of automotive industry experience. Dan Savoury, the new Vice Principal, joined the Academy earlier this year and also has a wealth of industry and training experience that will help us continue to improve our training which, in turn, benefits your business. I hope to use the experience gained in my previous sales and marketing roles within Ford to help our training continue to grow in scope and quality. It is a really exciting time to be a part of the Ford family; with new vehicles joining the range and new technology transforming the industry more widely. Good training is vital to our success and we continue to strive to achieve the highest standards and keep you up to date with this rapidly changing industry, from the technical training for the All-new Ford Mustang detailed on page 4, to ensuring our Commercial Vehicle Sales staff can give their customers the best advice with courses such as Commercial Vehicle Type Approval and Legislation on page 30. The success of our training programmes is demonstrated in this issue, with Chelsea Riddle from TrustFord in Bradford a great example of what the Ford Masters Apprenticeship scheme offers to young people, or the success that Mike Gates from Dinnages Ford in Burgess Hill has achieved with a university scholarship through the Henry Ford Academy. -

SMMT Puts Record Straight on Diesel Cars with New Nationwide Consumer Campaign Posted at 05:59 on 11 March 2015

Members' Login Search Navigation NEWS Home » News and Events » News » SMMT put s record st raight on diesel cars wit h new nat ionwide consumer campaign Back to list Related Posts SMMT puts record straight on diesel cars with new nationwide consumer campaign Posted at 05:59 on 11 March 2015. New poll shows almost three quarters (72%) of motorists against penalties for UK’s cleanest diesels 87% of UK adults unaware of the latest low emission vehicle technology SMMT calls for greater awareness of cleaner diesel tech to help guide policy makers London 11 March, 2015 The Society of Motor Manufacturers and Traders (SMMT) will today launch a nationwide consumer campaign to raise awareness about the latest low- emission car technology and challenge the increasing demonisation of diesel. A Diesel Facts myth-busting guide will be available at dieselfacts.co.uk and in leaflet form via car makers and dealers. It comes as new consumer research reveals widespread confusion about diesel technology that, if uncorrected, could limit adoption of the latest low emission vehicles and undermine the UK’s efforts to meet strict air quality and climate change obligations. Responding to a YouGov poll, 87% of UK adults said they were unaware of the latest Euro-6 vehicle emission technology, while 54% incorrectly blamed cars and commercial vehicles as the biggest cause of air pollution in the UK. Just under one in five (19%) of people surveyed correctly identified power stations as the biggest contributors of nitrogen oxides (NOx). In fact, it would take 42 million Euro-6 diesel cars (almost four times the number on the roads) to generate the same amount of NOx as one UK coal- fired power station. -

THE TIME Machine a Wonderful MG the Official Maga- for Santa to Drive Zine of the Gold to the Christmas Coast MG Car Club Party

THE TIME machine A wonderful MG The Official maga- for Santa to drive zine of the Gold to the Christmas Coast MG Car Club party. Here he is with his helper Registered by and other ladies! Australia Post Publication No. PP 444728-0010 February March 14 1 2 THE TIME MACHINE The OFFICIAL JOURNAL of the GOLD COAST MG CAR CLUB INC. Affi liated with the MG Car Club UK and C.A.M.S. Club email: [email protected] Club Web address: www.goldcoastmgcarclub.com.au Dave Godwin Ph 07 5537 4681 Mobile: 0412 029277 (President) email - [email protected] Cheryl Robinson Mobile 0466 627308 (Vice President) email - [email protected] Jean Bailey Ph 07 5530 7831 Mobile 0407 583534 (Treasurer) email - jean_bailey @ bigpond.com Marie Conway-Jones Ph 07 5591 2746 Mobile 0411 181725 (Secretary) email - [email protected] Brian Hockey Ph 02 6672 6950 Mobile 0408062890 (Membership) email - [email protected] Carole Cooke Ph 07 5536 9730 (Editor) email - [email protected] Stuart Duncan Mobile - 0405 402745 (Webmaster) email - [email protected] Ian Cowen Ph 07 5511 9128 (Committee) email - [email protected] Keith Ings Ph 07 5593 1484 Mobile 0414 349 918 (Committee) email - keith.ann1@bigpond Nicholas Tyler Mobile 0404 603 889 (Committee) email - [email protected] John Talbot Ph 07 5578 9972 Mobile 0412 958839 (Committee and LSIM Cordinator) email - [email protected] With Bruce Corr Ph 07 5535 3628 (Mid Week Runs Co-Ordinator) email - [email protected] Pam Everitt Ph 07 5539 1819 (Regalia) email - [email protected] NB. -

The Society of Motor Manufacturers and Traders Motor Industry Facts 2014

THE SOCIETY OF MOTOR MANUFACTURERS AND TRADERS MOTOR INDUSTRY FACTS 2014 CONTENTS WHAT IS SMMT? The Society of Motor Manufacturers and Traders (SMMT) supports and promotes the interests of the UK automotive industry at home and abroad. Working closely with member companies, SMMT acts as the voice of the motor industry, promoting its position to government, stakeholders and the media. SMMT represents more than 600 automotive companies in the UK, providing its members with a forum to voice opinions on issues affecting the automotive sector, guiding strategies and building positive relationships with government and regulatory authorities. As one of the largest and most influential trade associations operating in the UK, SMMT’s resources, reputation and unrivalled automotive data place it at the heart of the UK automotive industry. To find out how to join SMMT and for more information, visit www.smmt.co.uk/memberservices or e-mail [email protected]. www.smmt.co.uk CONTENTS 02 CONTENTS UK AUTOMOTIVE AT A GLANCE ................................. 4-5 REGISTRATIONS ........................................................ 16 Cars by fuel type ...........................................................................17 Private, fleet and business ...........................................................18 UK AUTOMOTIVE INDUSTRY: PROFILE ......................... 6 Top five cars by segment .........................................................19-21 Investment ......................................................................................6 -

The Society of Motor Manufacturers and Traders

The Society of Motor Manufacturers and Traders InternationalInternational Automotive Automotive Summit Summit 2424 November November 2009 2009 Chief executive’s welcome I am delighted to welcome you here this afternoon to SMMT’s first International Automotive Summit. We meet at an extremely important time, having endured the most difficult economic conditions, and this event gives us the chance to look beyond the recession and recognise the opportunities that lie ahead. Across the political spectrum there is widespread recognition that the UK cannot thrive on financial services alone. Manufacturing, and particularly automotive manufacturing, has a vital role to play in a more balanced economy and will be one of the generators of jobs and prosperity in the years ahead. Government has recognised the strategic national importance of our sector and through its support for the New Automotive Innovation and Growth Team’s report, has committed to a long-term partnership with the motor industry. In terms of our future, we know the global demand for motor vehicles will return. The fast growing markets in Brazil, India and China will continue to embrace personal mobility at faster rates and the replacement cycle for vehicles in developed markets will return. But this future demand will be for cleaner, safer and more fuel-efficient vehicles that can be developed and manufactured anywhere in the world. The challenge for the UK motor industry, and the government, is how to ensure the UK retains and grows its share of the developing global market. The UK’s automotive strengths – efficiency, productivity, innovative R&D and a flexible workforce have already attracted a diverse presence of vehicle manufacturers from Europe, Japan, Malaysia, China, Kuwait, India and the US. -

![Dfe Roundtable Final[1]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/9224/dfe-roundtable-final-1-989224.webp)

Dfe Roundtable Final[1]

22 June 2011 Schools Minister challenges engineering sector to wow young people and boost entry routes to UK industry. UK engineering chiefs gathered at the Department for Education on Wednesday 8 June to discuss what can be done to ensure the talent pipeline and adequately equip young people for the requirements of industry. Organised by EngineeringUK, Schools Minister Nick Gibb MP addressed a high-level roundtable attended by representatives from EngineeringUK, E.ON, BAE Systems, JCB, Jaguar Land Rover, Ford of Britain, the ODA, GKN, Rolls Royce, ICW UK, the Royal Academy of Engineering and Pearson UK. With almost half a million engineering enterprises in the UK, employing 4.5 million people, the engineering industry is one of the most significant drivers of the UK economy today. Demand is such that the UK needs to recruit an additional 587,000 workers between 2007 – 2017; however, falling numbers of young people available to work mean that the sector must act now to identify opportunities to attract and retain engineering talent. EngineeringUK’s own research shows that young people’s enthusiasm for science learning dips in Year 8, the crucial decision making moment for their future career path. More needs to be done to create excitement and revitalise young people’s perception of engineering, and to provide a route-map that takes young people from early years learning right through to vocational training or their degree. Paul Jackson, Chief Executive of EngineeringUK, said: “The meeting demonstrated the importance of collaboration between engineering business and the public sector. The businesses represented already play a significant role in education - through outreach projects with schools, work placements, apprenticeships and indeed the ongoing training and development of their staff. -

Former Ford Factory Wide Lane Southampton

Former Ford Factory Wide Lane Southampton Archaeological Evaluation for CgMs On behalf of Mountpark SOU1722 CA Project: 770434 CA Report: 16500 September 2016 Former Ford Factory Wide Lane Southampton Archaeological Evaluation SOU 1722 CA Project: 770434 CA Report: 16500 Document Control Grid Revision Date Author Checked by Status Reasons for Approved revision by A 16.09.16 Adam DDR Internal Edits REG Howard/Nicky review Garland B 22.09.16 Adam DDR Draft for Edits REG Howard/Nicky issue Garland C 04.09.16 Nicky DDR FINAL Edits requested SCCHET Garland by SCCHET This report is confidential to the client. Cotswold Archaeology accepts no responsibility or liability to any third party to whom this report, or any part of it, is made known. Any such party relies upon this report entirely at their own risk. No part of this report may be reproduced by any means without permission. © Cotswold Archaeology © Cotswold Archaeology Former Ford Factory, Wide Lane, Southampton: Archaeological Evaluation CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................ 5 2. ARCHAEOLOGICAL BACKGROUND ................................................................ 6 3. AIMS AND OBJECTIVES ................................................................................... 9 4. METHODOLOGY ............................................................................................... 10 5. RESULTS (FIGS 2-10) ....................................................................................... 11