Annual Atwood Bibliography 2018

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Approach to the Pedagogy of Beginning Music Composition: Teaching Understanding and Realization of the First Steps in Composing Music

AN APPROACH TO THE PEDAGOGY OF BEGINNING MUSIC COMPOSITION: TEACHING UNDERSTANDING AND REALIZATION OF THE FIRST STEPS IN COMPOSING MUSIC DOCUMENT Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Musical Arts in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Vera D. Stanojevic, Graduate Diploma, Tchaikovsky Conservatory ***** The Ohio State University 2004 Dissertation Committee: Approved By Professor Donald Harris, Adviser __________________________ Professor Patricia Flowers Adviser Professor Edward Adelson School of Music Copyright by Vera D. Stanojevic 2004 ABSTRACT Conducting a first course in music composition in a classroom setting is one of the most difficult tasks a composer/teacher faces. Such a course is much more effective when the basic elements of compositional technique are shown, as much as possible, to be universally applicable, regardless of style. When students begin to see these topics in a broader perspective and understand the roots, dynamic behaviors, and the general nature of the different elements and functions in music, they begin to treat them as open models for individual interpretation, and become much more free in dealing with them expressively. This document is not designed as a textbook, but rather as a resource for the teacher of a beginning college undergraduate course in composition. The Introduction offers some perspectives on teaching composition in the contemporary musical setting influenced by fast access to information, popular culture, and globalization. In terms of breadth, the text reflects the author’s general methodology in leading students from basic exercises in which they learn to think compositionally, to the writing of a first composition for solo instrument. -

The Woman-Slave Analogy: Rhetorical Foundations in American

The Woman-Slave Analogy: Rhetorical Foundations in American Culture, 1830-1900 Ana Lucette Stevenson BComm (dist.), BA (HonsI) A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at The University of Queensland in 2014 School of History, Philosophy, Religion and Classics I Abstract During the 1830s, Sarah Grimké, the abolitionist and women’s rights reformer from South Carolina, stated: “It was when my soul was deeply moved at the wrongs of the slave that I first perceived distinctly the subject condition of women.” This rhetorical comparison between women and slaves – the woman-slave analogy – emerged in Europe during the seventeenth century, but gained peculiar significance in the United States during the nineteenth century. This rhetoric was inspired by the Revolutionary Era language of liberty versus tyranny, and discourses of slavery gained prominence in the reform culture that was dominated by the American antislavery movement and shared among the sisterhood of reforms. The woman-slave analogy functioned on the idea that the position of women was no better – nor any freer – than slaves. It was used to critique the exclusion of women from a national body politic based on the concept that “all men are created equal.” From the 1830s onwards, this analogy came to permeate the rhetorical practices of social reformers, especially those involved in the antislavery, women’s rights, dress reform, suffrage and labour movements. Sarah’s sister, Angelina, asked: “Can you not see that women could do, and would do a hundred times more for the slave if she were not fettered?” My thesis explores manifestations of the woman-slave analogy through the themes of marriage, fashion, politics, labour, and sex. -

2014 Program

Kingston’s Readers and Writers Festival Program September 24–28, 2014 Holiday Inn Kingston Waterfront kingstonwritersfest.ca OUR MANDATE Kingston WritersFest, a charitable cultural organization, brings the best Welcome of contemporary writers to Kingston to interact with audiences and other artists for mutual inspiration, education, and the exchange of ideas that his has been an exciting year in the life of the Festival, as well literature provokes. Tas in the book world. Such a feast of great books and talented OUR MISSION Through readings, performance, onstage discussion, and master writers—programming the Festival has been a treat! Our mission is to promote classes, Kingston WritersFest fosters intellectual and emotional growth We continue many Festival traditions: we are thrilled to welcome awareness and appreciation of the on a personal and community level and raises the profile of reading and bestselling American author Wally Lamb to the International Marquee literary arts in all their forms and literary expression in our community. stage and Wayson Choy to deliver the second Robertson Davies lecture; to nurture literary expression. Ben McNally is back for the Book Lovers’ Lunch; and the Saturday Night BOARD OF DIRECTORS 2014 FESTIVAL COORDINators SpeakEasy continues, in the larger Bellevue Ballroom. Chair | Jan Walter Archivist | Aara Macauley We’ve added new events to whet your appetite: the Kingston Vice-Chairs | Michael Robinson, Authors@School, TeensWrite! | Dinner Club with a specially designed menu; a beer-sampling Jeanie Sawyer Ann-Maureen Owens event; and with kids events moved offsite, more events for adults on T Secretary Box Office Services T | Michèle Langlois | IO Sunday. -

Katniss Everdeen's Anxieties and Defense Mechanisms in Suzanne Collins' the Hunger Games

PLAGIAT MERUPAKAN TINDAKAN TIDAK TERPUJI KATNISS EVERDEEN'S ANXIETIES AND DEFENSE MECHANISMS IN SUZANNE COLLINS' THE HUNGER GAMES AN UNDERGRADUATE THESIS Presented as Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Sarjana Sastra in English Letters By MUHAMMAD RASYID HALIM Student Number: 134214154 DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH LETTERS FACULTY OF LETTERS UNIVERSITAS SANATA DHARMA YOGYAKARTA 2020 PLAGIAT MERUPAKAN TINDAKAN TIDAK TERPUJI KATNISS EVERDEEN'S ANXIETIES AND DEFENSE MECHANISMS IN SUZANNE COLLINS' THE HUNGER GAMES AN UNDERGRADUATE THESIS Presented as Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Sarjana Sastra in English Letters By MUHAMMAD RASYID HALIM Student Number: 134214154 DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH LETTERS FACULTY OF LETTERS UNIVERSITAS SANATA DHARMA YOGYAKARTA 2020 ii PLAGIAT MERUPAKAN TINDAKAN TIDAK TERPUJI A Sarjana Sastra Undergraduate Thesis KATNISS EYERDEEN'S ANXIETTES AND DEFENSE MECHANISMS IN SUZANI\E COLLINS' THE HUNGER By MUHAMMAD RASYID HALIM Student Number: 1342141 54 j{\ tq .z 6,2420 Advisor Iune 6,2020 Co-Advisor tlt PLAGIAT MERUPAKAN TINDAKAN TIDAK TERPUJI A Sarjana Sastra Undergraduate Thesis KATI{ISS EVERDEEN'S ANXTETIES AND DEFENSE MECHAI{ISMS IN SUZANNE COLLINS' THE HUNGER GAMES By MUIIAMMAD RASYID HALIM Student Number: 134214154 Defended before on the Board ofExaminers onJune 17,2018 and Declared Acceptable BOARD OF EXAMINERS Name Signature Chairperson : Drs. Hirmawan Wijanarka, M.Hum. Secretary : Dr. G. Fajar Sasrnita Aji, M.Hum. Member 1 : Ni Luh Putu Rosiandani, S.S., M.Hum. Member 2 : Drs. Hirmawan Wijanarka, M.Hum. Member 3 : Dr. G. Fajar Sasmita Aji, M.Hum. Yogyakarta, June 30, 2020 Faculty of Letters Dharma University Dean Iskarna, S.S., M. Hum. -

Download (515Kb)

European Community No. 26/1984 July 10, 1984 Contact: Ella Krucoff (202) 862-9540 THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT: 1984 ELECTION RESULTS :The newly elected European Parliament - the second to be chosen directly by European voters -- began its five-year term last month with an inaugural session in Strasbourg~ France. The Parliament elected Pierre Pflimlin, a French Christian Democrat, as its new president. Pflimlin, a parliamentarian since 1979, is a former Prime Minister of France and ex-mayor of Strasbourg. Be succeeds Pieter Dankert, a Dutch Socialist, who came in second in the presidential vote this time around. The new assembly quickly exercised one of its major powers -- final say over the European Community budget -- by blocking payment of a L983 budget rebate to the United Kingdom. The rebate had been approved by Community leaders as part of an overall plan to resolve the E.C.'s financial problems. The Parliament froze the rebate after the U.K. opposed a plan for covering a 1984 budget shortfall during a July Council of Ministers meeting. The issue will be discussed again in September by E.C. institutions. Garret FitzGerald, Prime Minister of Ireland, outlined for the Parliament the goals of Ireland's six-month presidency of the E.C. Council. Be urged the representatives to continue working for a more unified Europe in which "free movement of people and goods" is a reality, and he called for more "intensified common action" to fight unemployment. Be said European politicians must work to bolster the public's faith in the E.C., noting that budget problems and inter-governmental "wrangles" have overshadolted the Community's benefits. -

Abstract the Fear of the Known: Horror Media And

ABSTRACT THE FEAR OF THE KNOWN: HORROR MEDIA AND THE USE OF FEAR TO MAINTAIN POWER Dana Peterson, MA. Department of Sociology Northern Illinois University, 2018 Diane Rodgers, Director A new subgenre has begun emerging in the horror genre: “woke horror.” Texts within this subgenre reflect the increased awareness of injustices against minority groups in American society. Prior research on horror has long connected the fears presented onscreen with real-life social anxieties of the time. Utilizing an intersectional framework that is concerned with racial, gender, and sexual orientation minorities, I engaged in a discourse analysis of three woke horror texts from 2017: American Horror Story: Cult, The Handmaid’s Tale, and Get Out. Through multiple rounds of coding, I was able to uncover a variety of themes that distinguish who holds the power in these horror texts, who is subordinate, and how the new fears of the woke horror genre are used to control groups within the texts. The codes also revealed who in these texts are able to be the saviors of the rest of the subordinate group. The present study offers an important update to the literature on horror, both in the continuation of the connections between on-screen fears and real life, as well as an introduction to what is sure to continue to be a growing subgenre. NORTHERN ILLINOIS UNIVERSITY DE KALB, ILLINOIS MAY 2018 THE FEAR OF THE KNOWN: HORROR MEDIA AND THE USE OF FEAR TO MAINTAIN POWER BY DANA PETERSON ©2018 Dana Peterson A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE MASTER OF ARTS DEPARTMENT OF SOCIOLOGY Thesis Director: Diane M. -

Thomas Hardy: Scripting the Irrational

1 Thomas Hardy: Scripting the Irrational Alan Gordon Smith Submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Leeds York St John University School of Humanities, Religion and Philosophy April 2019 2 3 The candidate confirms that the work submitted is his own and that appropriate credit has been given where reference has been made to the work of others. This copy has been supplied on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. The right of Alan Gordon Smith to be identified as Author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. 4 5 Acknowledgements I am extremely grateful to have been in receipt of the valuable support, creative inspiration and patience of my principal supervisor Rob Edgar throughout my period of study. This has been aided by Jo Waugh’s meticulous attention to detail and vast knowledge of nineteenth-century literature and the early assistance of big Zimmerman fan JT. I am grateful to the NHS for still being on this planet, long may its existence also continue. Much thought and thanks must also go to my late, great Mother, who in the early stages of my life pushed me onwards, initially arguing with the education department of Birmingham City Council when they said that I was not promising enough to do ‘O’ levels. Tim Moore, stepson and good friend must also be thanked for his digital wizardry. Finally, I am immensely grateful to my wife Joyce for her valued help in checking all my final drafts and the manner in which she has encouraged me along the years of my research; standing right beside me as she has always done when I have faced other challenging issues. -

The Hunger Games: Katniss Everdeen's Effort to Gain American Pragmatism Goals in Terms of American Values Journal Article By

THE HUNGER GAMES: KATNISS EVERDEEN’S EFFORT TO GAIN AMERICAN PRAGMATISM GOALS IN TERMS OF AMERICAN VALUES JOURNAL ARTICLE BY IKA FITRI NAASA RIANDJI NIM 0911110184 STUDY PROGRAM OF ENGLISH DEPARTMENT OF LANGUAGES AND LITERATURE FACULTY OF CULTURAL STUDIES UNIVERSITAS BRAWIJAYA 2013 1 THE HUNGER GAMES: KATNISS EVERDEEN’S EFFORT TO GAIN AMERICAN PRAGMATISM GOALS IN TERMS OF AMERICAN VALUES IkaFitriNaasaRiandji Abstract As one of a popular American novel which was published recently, The Hunger Games composed by Suzanne Collins, provides a significant description about the manifestation of American values portrayed by the main character, KatnissEverdeen.Katniss’ efforts in the novel are in line with the principle of American Pragmatism, which later on can be analyzed by its relation with the idea of American values, the grounding idea of the framing of this great American philosophy. By applying a sociological approach, this study discover the existence of the two roots of American culture known as American values and American Pragmatism, are still preserved. Katniss successfully manifests the goals of American Pragmatism that certainly taken from American values’ idea through her struggle told in the novel. This result leads to the comprehension of how American values influence American’s mind in fulfilling their goals or achievements. Keywords: American Values, American Pragmatism, Manifestation of Effort, The Hunger Games. Literary work is the place where “humans as the part of society express their ideas, feelings, and experiences in various form” (Langland, 1984, p.4). It is also mentioned in Plato’s theory that literary work is an imitation of truth which had a tremendous influence upon early literary critics and theorists during the Renaissance and 19th century, many of whom often speculated as to the role and function of art as imitation of reality (Plato, 429-347 BCE). -

A Study of the Rap Music Industry in Bogota, Colombia by Laura

The Art of the Hustle: A Study of the Rap Music Industry in Bogota, Colombia by Laura L. Bunting-Hudson Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy under the Executive Committee of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2017 © 2017 Laura L. Bunting-Hudson All Rights Reserved ABSTRACT The Art of the Hustle: A Study of the Rap Music Industry in Bogota, Colombia Laura L. Bunting-Hudson How do rap artists in Bogota, Colombia come together to make music? What is the process they take to commodify their culture? Why are some rappers able to become socially mobile in this process, while others are less so? What is technology’s role in all of this? This ethnography explores those questions, as it carefully documents the strategies utilized by various rap groups in Bogota, Colombia to create social mobility, commoditize products and to create a different vision of modernity within the hip-hop community, as an alternative to the ideals set forth by mainstream Colombian society. Resistance Art Poetry (RAP), is said to have originated in the United States but has become a form of international music. In conducting ethnographic research from December of 2012 to October 2014, I was able to discover how rappers organize themselves politically, how they commoditize their products and distribute them to create various types of social mobilities. In this dissertation, I constructed models to typologize rap groups in Bogota, Colombia, which I call polities of rappers to discuss how these groups come together, take shape, make plans and execute them to reach their business goals. -

Katniss Everdeen's Character Development in Suzanne Collins

LEXICON Volume 5, Number 1, April 2018, 9-18 Katniss Everdeen’s Character Development in Suzanne Collins' The Hunger Games Trilogy Valeri Putri Mentari Ardi*, Bernadus Hidayat Universitas Gadjah Mada, Indonesia *Email: [email protected] ABSTRACT This research examines the character development of Katniss Everdeen, the protagonist in Suzanne Collins’ The Hunger Games trilogy. It attempts to investigate whether socioeconomic factors play a role in Katniss’s character development. To address this question, Marxism was adopted as the theoretical framework to analyze Katniss’s character development. The results of the research indicate that the development of Katniss Everdeen as a character is a product of the socioeconomic power struggle within the society, both coming from the socioeconomic classes and the two presidents in Panem. Keywords: character development, Marxism, power struggle, society. their lives. It creates socioeconomic power INTRODUCTION struggle within the society that is believed to In the past few years, the literary world has influence people on personal level, including been swarmed with numerous science fiction Katniss Everdeen, the main character of the novels. One of them is the best-selling young trilogy. adult series called The Hunger Games trilogy The protagonist, Katniss Everdeen, is a written by an American novelist Suzanne Collins. dynamic character who drives the plot This trilogy consists The Hunger Games, Catching significantly, and at the same is also influenced by Fire, and Mockingjay, the setting of which is a it. She is only sixteen years of age when the story dystopian future of North America. begins and physically looks nothing special According to. Abrams (1999), science fiction compared to other girls in the neighborhood, but represents “an imagined reality that is radically her life is no ordinary adventure. -

The Establishment Responds Power, Politics, and Protest Since 1945

PALGRAVE MACMILLAN TRANSNATIONAL HISTORY SERIES Akira Iriye (Harvard University) and Rana Mitter (University of Oxford) Series Editors This distinguished series seeks to: develop scholarship on the transnational connections of societies and peoples in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries; provide a forum in which work on transnational history from different periods, subjects, and regions of the world can be brought together in fruitful connection; and explore the theoretical and methodological links between transnational and other related approaches such as comparative history and world history. Editorial board: Thomas Bender University Professor of the Humanities, Professor of History, and Director of the International Center for Advanced Studies, New York University Jane Carruthers Professor of History, University of South Africa Mariano Plotkin Professor, Universidad Nacional de Tres de Febrero, Buenos Aires, and mem- ber of the National Council of Scientific and Technological Research, Argentina Pierre- Yves Saunier Researcher at the Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique, France Ian Tyrrell Professor of History, University of New South Wales. Published by Palgrave Macmillan: THE NATION, PSYCHOLOGY AND INTERNATIONAL POLITICS, 1870–1919 By Glenda Sluga COMPETING VISIONS OF WORLD ORDER: GLOBAL MOMENTS AND MOVEMENTS, 1880s–1930s Edited by Sebastian Conrad and Dominic Sachsenmaier PAN-ASIANISM AND JAPAN’S WAR, 1931–1945 By Eri Hotta THE CHINESE IN BRITAIN, 1800–PRESENT: ECONOMY, TRANSNATIONALISM, IDENTITY By Gregor Benton and Terence -

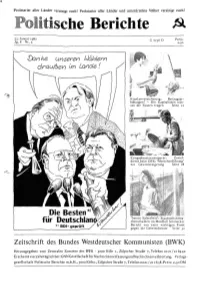

Litische Berichte Ä

Proletarier aller Länder vereinigt euch! Proletarier aller Länder und unterdrückte Völker vereinigt euch! nlitische O A © Berichte Ä 23. Januar 1987 G 7756 D Preis: Jg. 8 Nr. 2 2,50 r~ vCbn A0 Unseren IdcMern drqutöen im Lunde! Krankenversicherung: Beitragser höhungen! - Die Kapitalisten müs sen die Kosten tragen Seite 12 Kriegsdienstverweigerer: Zuviel dienst beim DRK: "Menschenführung" zur Gewinnsteigerung Seite 28 "Innere Sicherheit": Staatsschutzma chenschaften im Mordfall Schmücker Bericht von einer wichtigen Front *> BDI-geprüft gegen die Geheimdienste Seite 32 Zeitschrift des Bundes Westdeutscher Kommunisten (BWK) Herausgegeben vom Zentralen Komitee des BWK • 5000 Köln 1, Zülpicher Straße 7, Telefon 0221/216442 Erscheint vierzehntäglich bei: GNN Gesellschaft für Nachrichtenerfassung und Nachrichtenverbreitung, Verlags gesellschaft Politische Berichte m.b.H., 5000 Köln 1, Zülpicher Straße 7, Telefon 0221/211658.Preis: 2,50 DM Seite 2 Aus Verbänden und Parteien Politische Berichte 02/87 von Europas Christdemokraten warnte Aktuelles aus Politik Jüdische Zwangsarbeiter er davor, die NPD zu verketzern, denn und Wirtschaft erhalten Spottgeld auch diese Partei habe „wertvolle euro Ehemalige jüdische Zwangsarbeiter, päische Ordnungsvorstellungen“ Aus der Diskussion der Orga die in zehn Rüstungsbetrieben des G,DVZ“, 22.6.78). Die Paneuropaunion nisation: Erklärung zu den bevor Flick-Konzerns geschunden wurden, steht in enger Verbindung mit der „Ge stehenden Bundestagswahlen .... 4 sollen sich die 5 Millionen DM teilen, sellschaft fiir Menschenrechte“ (GfM), die die Feldmühle AG vor einem Jahr deren Bundesvorsitzender über deren Beschluß zu den Verhandlungen als Entschädigungssumme zu zahlen Selbstverständnis sagte: „es gelte, das zwischen Mitgliedern der Leitungen sich bereiterklärte. Ende 1986, als die ,Mittel Menschenrechte6 als ,Kampf von BWK und VSP........................