John Dowland (1563-1626): a Fancy Francesco

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

APPENDIX 1 Inventories of Sources of English Solo Lute Music

408/2 APPENDIX 1 Inventories of sources of English solo lute music Editorial Policy................................................................279 408/2.............................................................................282 2764(2) ..........................................................................290 4900..............................................................................294 6402..............................................................................296 31392 ............................................................................298 41498 ............................................................................305 60577 ............................................................................306 Andrea............................................................................308 Ballet.............................................................................310 Barley 1596.....................................................................318 Board .............................................................................321 Brogyntyn.......................................................................337 Cosens...........................................................................342 Dallis.............................................................................349 Danyel 1606....................................................................364 Dd.2.11..........................................................................365 Dd.3.18..........................................................................385 -

The Anthems of Thomas Ford (Ca. 1580-1648). Fang-Lan Lin Hsieh Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1989 The Anthems of Thomas Ford (Ca. 1580-1648). Fang-lan Lin Hsieh Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Hsieh, Fang-lan Lin, "The Anthems of Thomas Ford (Ca. 1580-1648)." (1989). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 4722. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/4722 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS The most advanced technology has been used to photo graph and reproduce this manuscript from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are re produced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand corner and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. -

Information to Users

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand corner and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6" x 9" black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. University Microfilms International A Bell & Howell Information Com pany 300 North Z eeb Road. Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 USA 313/761-4700 800/521-0600 Order Number 9227220 Aspects of early major-minor tonality: Structural characteristics of the music of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries Anderson, Norman Douglas, Ph.D. -

British Viol Consort Fretwork to Play Old and New Music at CMA October 12

British viol consort Fretwork to play old and new music at CMA October 12 by Daniel Hathaway You could say with some accuracy that Fretwork, the British viol consort, was an idea formed in Hell. Its early members Richard Boothby, Bill Hunt, and Richard Campbell first played together in the underworld scene in Monteverdi’s Orfeo, a production semi-staged in Barcelona in 1985 by Andrew Parrott’s Taverner Players. Those three minutes led to further performances, and now Fretwork is considered among the premier viol ensembles in the world. Most viol consorts stick to old music composed before the viola da gamba became extinct in England in the latter part of the 17th century. Fretwork is unusual in its equal embrace of contemporary music: on its website the group lists two dozen composers who have written works for them. Fretwork’s current five members, Asako Morikawa, Reiko Ichise, Sam Stadien, Emily Ashton, and Boothby (far right in the photo) will appear on the Cleveland Museum of Art’s Performing Arts series in Gartner Auditorium on Wednesday, October 12 at 7:30 pm. The program includes 16th and 17th century English consort music by John Taverner and Orlando Gibbons, works by contemporary composers Nico Muhly and Gavin Bryars, and a special performance of Norwegian composer Maja Ratkje’s River Mouth Echoes. Cleveland is one of ten cities Fretwork will visit on an American Tour that begins on October 6 in Montréal and ends on October 24 in Victoria, BC, with stops in Boston, Milwaukee, Wake Forest in North Carolina, Jackson in Mississippi, Austin and Lubbock in Texas, and Vancouver BC. -

Pavane and Galliard Anthony Holborne Introduction Music For

Pavane and Galliard Anthony Holborne Introduction These two short pieces belong to the genre known as ‘consort music’, a popular form of domestic music-making in Elizabethan England. The word ‘consort’ itself may have been a representation of the Italian term ‘concerto’ and the French ‘concert’, both of which at one time implied an ensemble of voices or instruments rather than any particular form of piece. Many works were composed in the years from about 1575 to the late seventeenth century both for consorts of viols, as in these pieces, or for mixed ensembles, known as ‘broken consorts’. The usual complement of a broken consort was lute, bandora, treble and bass viols, cittern and flute (the cittern was a wire-stringed instrument, in appearance similar to a lute but with flat back like that of a guitar; the bandora was of the same type but was a bass instrument). Thomas Morley (1557-c1603) scored his Consort Lessons (1599) for this combination, as did Philip Rosseter (c1575-1623) in his Lessons for Consort (1609). Consorts of viols began to appear in England from the time of Henry VIII, who in 1540 appointed to his court a complete consort of players from Italy. The earliest source of English consort music appears to be a Songbook of Henry VIII and many viols were found in his collection at the time of his death in 1547. Music for Consorts of Viols There were three main forms: • the In Nomine, originally based on the In Nomine section of the Benedictus from the Mass Gloria tibi Trinitas by John Taverner (c1495-1545) • the Fancy or Fantasia, a through-composed, usually imitative type of work • the Pavan and Galliard dance forms (singly or paired). -

Album Booklet

As our sweet Cords with Discords mixed be ENGLISH RENAISSANCE CONSORT MUSIC CONSORTIUM5 RECORDER QUINTET RES10155 Jerome Bassano (1559-1635) Edward Blankes (1582-1633) As our sweet Cords with Discords mixed be 1. Galliard [1:08] 13. A phancy [1:35] Alfonso Ferrabosco I (1543-1588) Alfonso Ferrabosco I English Renaissance Consort Music 2. In nomine II [1:42] 14. In nomine I [2:01] William Byrd (c. 1540-1623) William Brade 3. In nomine IV [2:22] 15. Coranto [0:46] William Brade (1560-1630) Christopher Tye Consortium5 4. Coranto [1:18] 16. In nomine IX ‘Re la re’ [1:14] Christopher Tye (c. 1505-1572) Antony Holborne (c. 1545-1602) 5. In nomine ‘Howld fast’ [1:17] 17. [Almaine] ‘The night watch’ [1:35] Emily Bloom 6. In nomine ‘Crye’ [1:36] Kathryn Corrigan William Byrd Osbert Parsley (1511-1585) 18. The leaves be green [3:48] Oonagh Lee 7. In nomine [2:24] Gail Macleod Christopher Tye Alfonso Ferrabosco II (1575-1628) 19. In nomine XI Roselyn Maynard 8. Dovehouse Pavan [3:23] ‘Farewell good one for ever’ [1:56] Christopher Tye Alfonso Ferrabosco II recorders 9. In nomine ‘Seldom sene’ [1:35] 20. Pavan V [3:20] About Consortium5: Robert Parsons (c. 1535-1572) John Dowland (1563-1626) ‘[Consortium5] played 10. In nomine III [1:42] 21. Mrs. Nichols’ Almain [0:56] with superb and consistent musicality’ 22. The Earl of Essex’s Galliard [1:13] Ipswich Star Christopher Tye 23. Captain Digorie Piper’s Galliard [1:17] 11. In nomine X ‘Saye so’ [1:06] ‘Consortium5 has earned all the praise critics Jerome Bassano can muster by reinventing consort music’ John Ward (1571-1638) 24. -

Semper Dowland

SEMPER DOWLAND 25 pieces by lutenist JOHN DOWLAND Newly arranged for guitar by Jeffry Hamilton Steele SEMPER DOWLAND 25 pieces by lutenist JOHN DOWLAND Arranged for Guitar by Jeffry Hamilton Steele ALMAINS PAVANS Mrs. Clifton’s Almain Piper’s Pavane Lady Hunsdon’s Puffe Lachrimae Semper Dowland Semper Dolens GALLIARDS Captain Digorie Piper’s Galliard FANTASIES Melancholy Galliard A Fancy (#6) Galliard to Lachrimae A Fancy (#7) John Dowland’s Galliard A Fantasie Mrs. Vaux’s Galliard A Fantasia Lady Clifton’s Spirit Farewell (an “In Nomine”) Earle of Essex, His Galliard Forlorn Hope Fancy Mr. Knight’s Galliard A Galliard (on a Bacheler galliard) OTHER A Galliard (on Walsingham) Mrs. Vaux’s Jig The Shoemaker’s Wife, A Toy Weep You No More, Sad Fountains Aloe When I played once for a man who both built and per- “Semper Dowland Semper Dolens”, where I used ideas formed on lutes he enthused that my Michael Cone guitar, from the Jane Pickering Lute Book. While I generally made with its greater projection and sustain, brought something use of the Poulton/Lam rendering of voicings, I frequently to lute music that his period instruments could not. And, reinterpreted voice movement – either out of technical or with its bright high end and thin bass, it didn’t have the motivic considerations. Bearing in mind that many of inappropriately lush sound of the modern guitar. these pieces came down to us from one-of-a-kind lute This inspired me to re-examine The Collected Lute books written out in the hand of a particular player (often Music of John Dowland (Faber Music, Diana Poulton and an amateur), I have made composer’s choices in passages Basil Lam, editors), which I had purchased twenty years that I felt could help the music better live up to its earlier. -

In Nomine II Here It Is from the Parsons 7-Part in Nomine No

In Nominefretwork II There are several important moments in the tune. In Nomine II Here it is from the Parsons 7-part In nomine No. 5: ver thirty years ago, Fretwork made 1. Slow (In Nomine in 5 parts) Nico Muhly (b.1981) 8.12 its first recording – well, technically speaking it was the second album Robert Parsons (1535-1572) 2.29 2. In Nomine IV in 7 parts to be recorded, but the first to be released – and it was called ‘In 3. In Nomine V in 7 parts Robert Parsons 3.03 Onomine’, which consisted mainly of 16th-century 4. In Nomine in 11/4 John Bull (c.1562-1628) 5.37 examples of this remarkable instrumental form. 5. Proportions to the minim John Baldwin (1560-1615) 2.31 While this isn’t an anniversary of that release, we want to look both back to that first release and 6. Upon In Nomine 1592 John Baldwin 1.36 forward, to bring the genre up to date. There were The opening rising and falling third is often imitated; several examples of the In nomine and related The sixth and seventh notes moves the tonality away 7. In Nomine 1606 John Baldwin 2.19 forms that we didn’t or couldn’t record in 1987, from the opening D into F; At the end of the second and this album seeks to complete the project. line here, it reaches its highest point and then (third 8. In Nomine in 6 Parts, No. 1 Alfonso Ferrabosco II (1575-1628) 3.45 note, third line) we have a semi-tone rise and fall, The form was created unwittingly by John Taverner one of only two in the tune. -

Symphony No.2 and the Text Setting of Henry Purcell's Dido and Aeneas

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School March 2020 Symphony No.2 and the Text Setting of Henry Purcell's Dido and Aeneas Sungho Kim Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the Composition Commons Recommended Citation Kim, Sungho, "Symphony No.2 and the Text Setting of Henry Purcell's Dido and Aeneas" (2020). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 5175. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/5175 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. SYMPHONY NO.2 AND THE TEXT SETTING OF HENRY PURCELL’S DIDO AND AENEAS A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The School of Music by Sungho Kim B.M., Berklee College of Music, 2008 M.M., Louisiana State University, 2013 May 2020 PREFACE Before studying composition at Louisiana State University under the guidance of Dr. Dinos Constantinides, Boyd Professor of Composition, I mainly wrote tonal pieces. I clearly remember his first lesson, when he introduced me to atonal music. It was like a new language for me, which was quite amazing and fascinating. Since then, one of my primary concerns has been mixing tonal and atonal music in one piece, and Symphony No. -

75TH SEASON of CONCERTS October 23, 2016 • National Gallery of Art Lestrange Viols

75TH SEASON OF CONCERTS october 23, 2016 • national gallery of art LeStrange Viols. Photo by Brian Hall PROGRAM 3:30 • West Building, West Garden Court LeStrange Viols Kivie Cahn-Lipman, tenor viol Douglas Kelley, bass viol Loren Ludwig, treble viol James Waldo, bass viol Zoe Weiss, treble viol The Duarte Family: A Musical Household in the Age of Rembrandt Peter Philips (1560 – 1628) Intermission Pavan and Galliard Sweelinck Leonora Duarte (c. 1610 – 1678) Veuilles, Seigneur Sinfonia No. 5 John Bull (1562 – 1628) Sweelinck In Nomine Pavana Philippi Fantasia “A Leona” Duarte Anonymous (c. 1500), from O Cancioneiro Sinfonia No. 3 Quié te traxo el cavallero Sinfonia No. 4 Anonymous, from O Cancioneiro Frescobaldi Cogoxa del mal presente Canzon sesta detta La Presenti Duarte Lobo (1564 – 1646) Missa “Dum Aurora” Kyrie Sweelinck Missa “Dum Aurora” Gloria Fantasia Chromatica Cornelis Schuyt (1557 – 1616) Nicolaus à Kempis (1600 – 1676) Illustre Cavallier Symphonia no. 1 a5 Girolamo Frescobaldi (1583 – 1643) Recercar Settimo Duarte Sinfonia No. 6 Variations on L’Aria del Gran Duca Peter Philips, Jan Pieterszoon Sweelinck (1562 – 1621), and Peeter Cornet (c. 1570 – 1633) 75th Season • 3 The Musicians LeStrange Viols formed in 2014 to record the modern premiere of William Cranford’s consort music. By that time the musicians of LeStrange had already established themselves as a crack team of American consort players. Their many previous appearances together in diverse musical combinations and their experience in acclaimed American ensembles allow the ensemble to craft refined and vigorous performances of intricate gems of the consort repertory. LeStrange’s debut CD made the New Yorker’s list of notable recordings of 2015. -

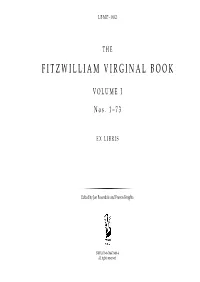

Page 1 L B M P – 0 0 2 T H E

L B M P – 0 0 2 T H E F I T Z W I L L I A M V I R G I N A L B O O K V O L U M E I N o s . 1 – 7 3 E X L I B R I S Edited by Jon Baxendale and Francis Knights ISMN 979-0-706670-09-6 All rights reserved. C O N T E N T S P R E F A C E T H E M U S I C 1. Editing the Fitzwilliam Virginal Book i 1 Walsingham John Bull 2 2. Historical context i 2 Fantasia John Mundy 26 Fantasia, Faire Wether, etc. John Mundy 32 3. The copyist ii 3 4 Pavana Ferdinando Richardson 37 4. The manuscript 5 Variatio Ferdinando Richardson 39 i. Physical attributes iv 6 Galiarda Ferdinando Richardson 43 ii. Content v iii. Notation and technique v 7 Variation Ferdinando Richardson 45 iv. Marginalia and emendations ix 8 Fantasia William Byrd 49 v. Plenary notes xi 9 Goe from my Window Thomas Morley 55 5. The music 10 Jhon come kisse me now William Byrd 60 i. Composers and sources xi 11 Galliarda to my Lord Lumleys Pavan John Bull 67 ii. Dances xiii 12 Nancie Thomas Morley 70 iii. Variations xv 13 Pavana [Trumpet Pavan] John Bull 76 iv. Grounds xiv 14 Alman Anon. 79 v. Fantasias xvi 15 Robin John Mundy 80 vi. Intabulations of vocal music xvii 16 Pavana Anon. 83 vii. Cantus firmus pieces xvii 17 Galiarda John Bull 85 viii. -

Fretwork at the Cleveland Museum of Art (October 12) by Nicholas Jones

Fretwork at the Cleveland Museum of Art (October 12) by Nicholas Jones Music for the instrument that the English called the viol and the Italians the viola da gamba flourished during the tumultuous changes in Europe in the 16th and 17th centuries. The contemplative, intimate sound of a consort of viols must have been a welcome relief from fires, plagues, religious wars, revolutions, and other sudden and unpredictable catastrophes. Viol consorts implied the opposite of Fortune’s wheel: the steady companionship of friends, both players and listeners, coming together in the appreciation of a quiet artistry. At the death in 1695 of Henry Purcell, arguably the greatest of composers for viol consort, those instruments — treble, tenor, and bass — swiftly fell out of favor, displaced by their louder and more versatile cousins, the violin, viola, and cello. In the 20th and 21st centuries, the viol consort has experienced a rebirth parallel to the rediscovery of Baroque music, a new exploration of the subtle and humane sonic world of consort music. At the center of that rebirth is the British viol consort Fretwork, now celebrating its 30th anniversary with an extensive North American tour that included a stop last week on the Cleveland Museum of Art’s Performing Arts series. The group’s name refers to one of the viol’s distinguishing features. Frets, as on a guitar, run down the fingerboard and allow the performers to play with a wonderful precision of intonation. Five players constitute Fretwork, led with a gentle hand by one of the consort’s founders, Richard Boothby.