Theological Studies, Inc

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Development of Marian Doctrine As

INTERNATIONAL MARIAN RESEARCH INSTITUTE UNIVERSITY OF DAYTON, OHIO in affiliation with the PONTIFICAL THEOLOGICAL FACULTY MARIANUM ROME, ITALY By: Elizabeth Marie Farley The Development of Marian Doctrine as Reflected in the Commentaries on the Wedding at Cana (John 2:1-5) by the Latin Fathers and Pastoral Theologians of the Church From the Fourth to the Seventeenth Century A Dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctorate in Sacred Theology with specialization in Marian Studies Director: Rev. Bertrand Buby, S.M. Marian Library/International Marian Research Institute University of Dayton 300 College Park Dayton, OH 45469-1390 2013 i Copyright © 2013 by Elizabeth M. Farley All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America Nihil obstat: François Rossier, S.M., STD Vidimus et approbamus: Bertrand A. Buby S.M., STD – Director François Rossier, S.M., STD – Examinator Johann G. Roten S.M., PhD, STD – Examinator Thomas A. Thompson S.M., PhD – Examinator Elio M. Peretto, O.S.M. – Revisor Aristide M. Serra, O.S.M. – Revisor Daytonesis (USA), ex aedibus International Marian Research Institute, et Romae, ex aedibus Pontificiae Facultatis Theologicae Marianum, die 22 Augusti 2013. ii Dedication This Dissertation is Dedicated to: Father Bertrand Buby, S.M., The Faculty and Staff at The International Marian Research Institute, Father Jerome Young, O.S.B., Father Rory Pitstick, Joseph Sprug, Jerome Farley, my beloved husband, and All my family and friends iii Table of Contents Prėcis.................................................................................. xvii Guidelines........................................................................... xxiii Abbreviations...................................................................... xxv Chapter One: Purpose, Scope, Structure and Method 1.1 Introduction...................................................... 1 1.2 Purpose............................................................ -

Sacramental Signification: Eucharistic Poetics from Chaucer to Milton

Sacramental Signification: Eucharistic Poetics from Chaucer to Milton Shaun Ross Department of English McGill University, Montreal August 2016 A thesis submitted to McGill University in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy © Shaun Ross 2016 i Table of Contents Abstract……………………………………………………………………………………………ii Resumé……………………………………………………………………………………………iv Acknowledgements…………………………………………………………………………….....vi Introduction………………………………………………………………………………………..1 Chapter One: Medieval Sacraments: Immanence and Transcendence in The Pearl-poet and Chaucer………...23 Chapter Two: Southwell’s Mass: Sacrament and Self…………………………………………………………..76 Chapter Three: Herbert’s Eucharist: Giving More……………………………………………………………...123 Chapter Four: Donne’s Communions………………………………………………………………………….181 Chapter Five: Communion in Two Kinds: Milton’s Bread and Crashaw’s Wine……………………………. 252 Epilogue: The Future of Presence…………………………………………………………………………325 Works Cited…………………………………………………………………………………….330 ii Abstract This dissertation argues that in early modern England the primary theoretical models by which poets understood how language means what it means were applications of eucharistic theology. The logic of this thesis is twofold, based firstly on the cultural centrality of the theology and practice of the eucharist in early modern England, and secondly on the particular engagement of poets within that social and intellectual context. My study applies this conceptual relationship, what I call “eucharistic poetics,” to English religious and -

Modern Devotion the Northern Renaissance and Religious

Turning Points:God’s Faithfulness in Christian History 4. Religious Awakening: Modern Devotion below: Begijnhof/ Beguinage, Bruges Context : Renaissance 1300-1500 “Renaissance”= re-birth / discovery of “Classical Ancient World”= Greece & Roman (600 BC--300 AD) “Humanism” = method to recover & study ancient texts. Discovery of ancient wisdom challenged existing authorities (church, kings): “Veritas, non auctoritas facit legem” (truth, not authority makes the law); truth in original texts & languages: Hebrew, Greek, Aramaic, Arabic, classical Latin. All Truth is God’s Truth Arthur F. Holmes, All Truth Is God’s Truth (Eerdmans, 1977). Long-time Wheaton College philosopher 2 Rise of Spirituality Problem of “Spirituality” for medieval laity & individual: (1) Few “religious” (nuns), monks, & priests w/some access to spirituality; (2) Laity mediated only through institutional Christendom (& rise of papacy). Lacked: access to Bible (esp. own language); God very distant (in heaven judging) & Jesus divinity, not humanity; no developed sense of individual/personal piety; almost no education about doctrine. CHANGE 1. Renaissance: 1300-1500 = re-birth of antiquity. 2. Christology: from almost solely divine Jesus to more human Jesus. 3. Mysticism allowed individual quest to know God & Self with heightened awareness of role of “conscience” & individual responsibility. Rise of Spirituality 4. “Devotio Moderna ” (modern devotion) movement northern Europe: Beguines, Brethren of the Common Life, & new Augustinian Order1256, education & publication. 5. Crises 14th c.: breakdown Christendom (2-3 popes);100 Yrs. War; Bubonic Plague; Peasant revolts. 6. Christian Humanism & spread of handbooks/manuals (scholarly base) & devotional materials. A balance b/w FAITH & REASON = goal. Crisis of Authority: Breakdown of Christendom Great Schism (1378-1417) SUPPORT Avignon: Kingdoms of France, Two popes: Avignon & Rome. -

John Calvin and the Brethren of the Common Life

JOHN CALVIN AND THE BRETHREN OF THE COMMON LIFE KENNETH A. STRAND Andrews University A number of the most prominent leaders in the religious history of western Europe during the 15th and 16th centuries had direct contact with the Catholic reform group known as the Brethren of the Common Life. Such was true, for example, of Desiderius Erasmus and Martin Luther, both of whom during their youth had been students under the Brethren. However, in the case of John Calvin, evidence of similar direct contact with the Brethren is lacking; in fact, this group did not establish any houses, dormitories for students, or schooIs in France and Switzerland, the two countries where Calvin spent most of his fife. Nevertheless, there is evidence that the infiuence of the Brotherhood did reach him in several significant ways. It is the purpose of the present brief essay to provide an overview of two main avenues through which John Calvin quite early in his career came in touch with the ideals and practices fostered by the Brethren of the Common Life: (1)his education at the College of Montaigu in Paris, and (2) his contact with the "Fabrisian Reformers." A third line of influence from that Brotherhood reached him later through his association with such men as Johann Sturm and Martin Bucer in Strassburg, both of whom had had contact with representatives of the Brotherhood. However, this third line of influence deserves separate treatment and hence will not be included hereml 1. The Brethren of the Cmmn Life Before we proceed to a discussion of the influence of the It is the writer's hope to present a brief article on this topic in a future issue of AUSS. -

In Ecclesia Nostra: the Collatiehuis in Gouda and Its Lieux De Savoir." Le Foucaldien 7, No

In Ecclesia Nostra: The Collatiehuis in Gouda and Its Lieux de Savoir RESEARCH PIETER H. BOONSTRA ABSTRACT CORRESPONDING AUTHOR: Pieter H. Boonstra This article will show how the concept of lieux de savoir as theorized by Christian Jacob University of Groningen, NL provides an intriguing framework from which to examine the interactions between [email protected] laypeople and religious professionals and the transmission of knowledge in the late medieval city, by applying it to the Collatiehuis in Gouda. Here, religious knowledge was shaped and communicated in the interaction between the Brothers of the Common KEYWORDS: Life and visiting laypeople. The separate rooms in which these interactions took spatiality; communication of place, as well as the location of the house within the city, influenced the circulation knowledge; collatio; lieux de of knowledge. Aside from this spatial approach, the article will also propose that the savoir texts used during these meetings can be considered their own lieux de savoir as they played an important role in shaping and communicating religious knowledge between TO CITE THIS ARTICLE: the lay and religious participants of the collatio. Boonstra, Pieter H. "In Ecclesia Nostra: The Collatiehuis in Gouda and Its Lieux de Savoir." Le foucaldien 7, no. 1 (2021): 5, 1–13. DOI: https:// doi.org/10.16995/lefou.93 1. INTRODUCTION Boonstra 2 Le foucaldien In the year 1445, a small community of Brothers of the Common Life took up residence in DOI: 10.16995/lefou.93 the Dutch city of Gouda, in a house located in the Spieringstraat. This community represented an urban branch of the Devotio moderna or Modern Devotion, the most renowned religious movement in the late medieval Low Countries. -

The Source and Application of Thomas Müntzer's Theology of Divination in His Marginal Notes on Tertullian

Concordia Seminary - Saint Louis Scholarly Resources from Concordia Seminary Master of Sacred Theology Thesis Concordia Seminary Scholarship 5-21-2021 The Source and Application of Thomas Müntzer's Theology of Divination in His Marginal Notes on Tertullian Roger Drinnon Concordia Seminary, St. Louis, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.csl.edu/stm Part of the Biblical Studies Commons, Christian Denominations and Sects Commons, Christianity Commons, History of Christianity Commons, Liturgy and Worship Commons, Religious Thought, Theology and Philosophy of Religion Commons, and the Renaissance Studies Commons Recommended Citation Drinnon, Roger, "The Source and Application of Thomas Müntzer's Theology of Divination in His Marginal Notes on Tertullian" (2021). Master of Sacred Theology Thesis. 399. https://scholar.csl.edu/stm/399 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Concordia Seminary Scholarship at Scholarly Resources from Concordia Seminary. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master of Sacred Theology Thesis by an authorized administrator of Scholarly Resources from Concordia Seminary. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE SOURCE AND APPLICATION OF THOMAS MÜNTZER’S THEOLOGY OF DIVINATION IN HIS MARGINAL NOTES ON TERTULLIAN A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of Concordia Seminary, St. Louis, Department of Historical Theology in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Sacred Theology By Roger Andrew Drinnon May, 2021 Approved by: Rev. Dr. Timothy Dost Thesis Advisor Rev. Dr. Joel Elowsky Reader Rev. Dr. Benjamin Haupt Reader © 2021 by Roger Andrew Drinnon. All rights reserved. ii To my father, Roger for giving me the love of learning. -

Devotion and Obedience: a Devotio Moderna Construction of St Bridget of Sweden in Lincoln Cathedral Chapter Manuscript 114

Devotion and Obedience: A devotio moderna construction of St Bridget of Sweden in Lincoln Cathedral Chapter Manuscript 114 Sara Danielle Mederos Doctor of Philosophy October 2016 Devotion and Obedience: A devotio moderna construction of St Bridget of Sweden in Lincoln Cathedral Chapter Manuscript 114 Sara Danielle Mederos A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the University of Lincoln for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy October 2016 2 Abstract This thesis analyses the construction of the pious lay female in Lincoln Cathedral Manuscript MS 114, through the example of Saint Bridget of Sweden. MS 114 is a devotional manuscript compiled of nineteen different, individual, articles. These nineteen articles are arranged in two, nearly equal, parts. The first part includes several Birgittine texts whereas the second part provides a more thematic approach, emphasising the virtues of humility, chastity, and overall spiritual obedience. Compiled in the Netherlands, sometime during the early fifteenth century, MS 114’s articles were purposely chosen to form a single compilation and was meant to be read as an enhancement of one’s devotion. By analysing the contents of MS 114, its date and provenance, and putting it in the context of the religious movements of its original time and place, this thesis argues that MS 114 was an early manuscript of the devotio moderna movement; a religious movement which attracted many lay devotees and particular female members and which emphasised the use of literature and, in particular, of written examples of holy, female lay lives. MS 114 uses the life of Bridget of Sweden, other works about her, and extracts from other theological texts to explore two devotio moderna virtues. -

New Readings of Heinrich Suso's Horologium Sapientiae

New Readings of Heinrich Suso’s Horologium sapientiae Jon Øygarden Flæten Dissertation submitted for the degree of philosophiae doctor (ph.d.) Faculty of Theology, University of Oslo, 2013 © Jon Øygarden Flæten, 2013 Series of dissertations submitted to the Faculty of Theology,University of Oslo No. 46 ISSN 1502-010X All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without permission. Cover: Inger Sandved Anfinsen. Printed in Norway: AIT Oslo AS, 2013. Produced in co-operation with Akademika publishing. The thesis is produced by Akademika publishing merely in connection with the thesis defence. Kindly direct all inquiries regarding the thesis to the copyright holder or the unit which grants the doctorate. Akademika publishing is owned by The University Foundation for Student Life (SiO) 1 Acknowledgements This work has been made possible by a scholarship from the Faculty of Theology at the University of Oslo. I am grateful to the factuly for this opportunity and for additional funding, which has enabled me to participate on various conferences. Professor Tarald Rasmussen has been my supervisor for several years, and I am deeply grateful for steady guidance, encouragement and for many inspiring con- versations, as well as fruitful cooperation on various projects. Among many good colleauges at the faculty I especially want to thank Eivor Oftestad, Kristin B. Aavitsland, Sivert Angel, Bjørn Ole Hovda, Helge Årsheim, Halvard Johannesen, and Vemund Blomkvist. I also want to express my thanks to the Theological Library for their services, and to Professor Dag Thorkildsen. This study is dedicated to my parents, Helga Øygarden and Ole Jacob Flæten. -

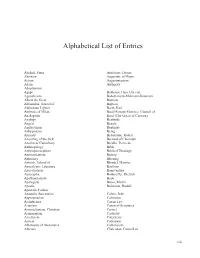

A-Z Entries List

Alphabetical List of Entries Abelard, Peter Attributes, Divine Abortion Augustine of Hippo Action Augustinianism Adam Authority Adoptionism Agape Balthasar, Hans Urs von Agnosticism Bañezianism-Molinism-Baianism Albert the Great Baptism Alexandria, School of Baptists Alphonsus Liguori Barth, Karl Ambrose of Milan Basel-Ferrara-Florence, Council of Anabaptists Basil (The Great) of Caesarea Analogy Beatitude Angels Beauty Anglicanism Beguines Anhypostasy Being Animals Bellarmine, Robert Anointing of the Sick Bernard of Clairvaux Anselm of Canterbury Bérulle, Pierre de Anthropology Bible Anthropomorphism Biblical Theology Antinomianism Bishop Antinomy Blessing Antioch, School of Blondel, Maurice Apocalyptic Literature Boethius Apocatastasis Bonaventure Apocrypha Bonhoeffer, Dietrich Apollinarianism Book Apologists Bucer, Martin Apostle Bultmann, Rudolf Apostolic Fathers Apostolic Succession Calvin, John Appropriation Calvinism Architecture Canon Law Arianism Canon of Scriptures Aristotelianism, Christian Carmel Arminianism Casuistry Asceticism Catechesis Aseitas Catharism Athanasius of Alexandria Catholicism Atheism Chalcedon, Council of xiii Alphabetical List of Entries Character Diphysitism Charisma Docetism Chartres, School of Doctor of the Church Childhood, Spiritual Dogma Choice Dogmatic Theology Christ/Christology Donatism Christ’s Consciousness Duns Scotus, John Chrysostom, John Church Ecclesiastical Discipline Church and State Ecclesiology Circumincession Ecology City Ecumenism Cleric Edwards, Jonathan Collegiality Enlightenment -

Word & Image Henry Suso's Horologium

This article was downloaded by: [Rozenski, Steven] On: 27 October 2010 Access details: Access Details: [subscription number 928675093] Publisher Routledge Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: Mortimer House, 37- 41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK Word & Image Publication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information: http://www.informaworld.com/smpp/title~content=t716100761 Henry Suso's Horologium Sapientiae in fifteenth-century France: images of reading and writing in Brussels Royal Library MS IV 111 Steven Rozenski Jr. Online publication date: 27 October 2010 To cite this Article Rozenski Jr., Steven(2010) 'Henry Suso's Horologium Sapientiae in fifteenth-century France: images of reading and writing in Brussels Royal Library MS IV 111', Word & Image, 26: 4, 364 — 380 To link to this Article: DOI: 10.1080/02666281003603146 URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/02666281003603146 PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE Full terms and conditions of use: http://www.informaworld.com/terms-and-conditions-of-access.pdf This article may be used for research, teaching and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproduction, re-distribution, re-selling, loan or sub-licensing, systematic supply or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. The publisher does not give any warranty express or implied or make any representation that the contents will be complete or accurate or up to date. The accuracy of any instructions, formulae and drug doses should be independently verified with primary sources. The publisher shall not be liable for any loss, actions, claims, proceedings, demand or costs or damages whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with or arising out of the use of this material. -

An Introductory Dictionary of Theology and Religious Studies

An Introductory Dictionary of Theology and Religious Studies An Introductory Dictionary of Theology and Religious Studies Edited by Orlando O. Espín and James B. Nickoloff A Michael Glazier Book LITURGICAL PRESS Collegeville, Minnesota www.litpress.org A Michael Glazier Book published by Liturgical Press. Cover design by David Manahan, o.s.b. Cover symbol by Frank Kacmarcik, obl.s.b. © 2007 by Order of Saint Benedict, Collegeville, Minnesota. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form, by print, microfilm, microfiche, mechanical recording, photocopying, translation, or by any other means, known or yet unknown, for any purpose except brief quotations in reviews, without the previous written permission of Liturgical Press, Saint John’s Abbey, P.O. Box 7500, Collegeville, Minnesota 56321-7500. Printed in the United States of America. 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data An introductory dictionary of theology and religious studies / edited by Orlando O. Espín and James B. Nickoloff. p. cm. “A Michael Glazier book.” ISBN-13: 978-0-8146-5856-7 (alk. paper) 1. Religion—Dictionaries. 2. Religions—Dictionaries. I. Espín, Orlando O. II. Nickoloff, James B. BL31.I68 2007 200.3—dc22 2007030890 We dedicate this dictionary to Ricardo and Robert, for their constant support over many years. Contents List of Entries ix Introduction and Acknowledgments xxxi Entries 1 Contributors 1519 vii List of Entries AARON “AD LIMINA” VISITS ALBIGENSIANS ABBA ADONAI ALBRIGHT, WILLIAM FOXWELL ABBASIDS ADOPTIONISM -

The Holy See

The Holy See BENEDICT XVI GENERAL AUDIENCE Paul VI Audience Hall Wednesday, 9 February 2011 [Video] Saint Peter Canisius Dear Brothers and Sisters, Today I want to talk to you about St Peter Kanis, Canisius in the Latin form of his surname, a very important figure of the Catholic 16th century. He was born on 8 May 1521 in Wijmegen, Holland. His father was Burgomaster of the town. While he was a student at the University of Cologne he regularly visited the Carthusian monks of St Barbara, a driving force of Catholic life, and other devout men who cultivated the spirituality of the so-called devotio moderna [modern devotion]. He entered the Society of Jesus on 8 May 1543 in Mainz (Rhineland — Palatinate), after taking a course of spiritual exercises under the guidance of Bl. Pierre Favre, Petrus [Peter] Faber, one of St Ignatius of Loyola’s first companions. He was ordained a priest in Cologne. Already the following year, in June 1546, he attended the Council of Trent, as the theologian of Cardinal Otto Truchsess von Waldburg, Bishop of Augsberg, where he worked with two confreres, Diego Laínez and Alfonso Salmerón. In 1548, St Ignatius had him complete his spiritual formation in Rome and then sent him to the College of Messina to carry out humble domestic duties. 2 He earned a doctorate in theology at Bologna on 4 October 1549 and St Ignatius assigned him to carry out the apostolate in Germany. On 2 September of that same year he visited Pope Paul III at Castel Gandolfo and then went to St Peter’s Basilica to pray.