CHINESE LITERATURE Compiled from from Compton's Living Encyclopedia On

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Utopia/Wutuobang As a Travelling Marker of Time*

The Historical Journal, , (), pp. – © The Author(s), . Published by Cambridge University Press. This is an Open Access article, distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives licence (http://creativecommons.org/ licenses/by-nc-nd/./), which permits non-commercial re-use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is unaltered and is properly cited. The written permission of Cambridge University Press must be obtained for commercial re-use or in order to create a derivative work. doi:./SX UTOPIA/WUTUOBANG AS A TRAVELLING MARKER OF TIME* LORENZO ANDOLFATTO Heidelberg University ABSTRACT. This article argues for the understanding of ‘utopia’ as a cultural marker whose appearance in history is functional to the a posteriori chronologization (or typification) of historical time. I develop this argument via a comparative analysis of utopia between China and Europe. Utopia is a marker of modernity: the coinage of the word wutuobang (‘utopia’) in Chinese around is analogous and complementary to More’s invention of Utopia in ,inthatbothrepresent attempts at the conceptualizations of displaced imaginaries, encounters with radical forms of otherness – the European ‘discovery’ of the ‘New World’ during the Renaissance on the one hand, and early modern China’sown‘Westphalian’ refashioning on the other. In fact, a steady stream of utopian con- jecturing seems to mark the latter: from the Taiping Heavenly Kingdom borne out of the Opium wars, via the utopian tendencies of late Qing fiction in the works of literati such as Li Ruzhen, Biheguan Zhuren, Lu Shi’e, Wu Jianren, Xiaoran Yusheng, and Xu Zhiyan, to the reformer Kang Youwei’s monumental treatise Datong shu. -

Shijing and Han Yuefu

SONGS THAT TOUCH OUR SOUL A COMPARATIVE STUDY OF FOLK SONGS IN TWO CHINESE CLASSICS: SHIJING AND HAN YUEFU by Yumei Wang A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Master of Art Graduate Department of the East Asian Studies University of Toronto © Yumei Wang 2012 SONGS THAT TOUCH OUR SOUL A COMPARATIVE STUDY OF FOLK SONGS IN TWO CHINESE CLASSICS: SHIJING AND HAN YUEFU Yumei Wang Master of Art Graduate Department of the East Asian Studies University of Toronto 2012 Abstract The subject of my thesis is the comparative study of classical Chinese folk songs. Based on Jeffrey Wainwright, George Lansing Raymond, and Liu Xie’s theories, this study was conducted from four perspectives: theme, content, prosody structure and aesthetic features. The purposes of my thesis are to trace the originality of 160 folk songs in Shijing and 47 folk songs in Han yuefu , to illuminate the origin of Chinese folk songs and to demonstrate the secularism reflected in Chinese folk songs. My research makes contribution to the following four areas: it explores the relation between folk songs in Shijing and Han yuefu and compares the similarities and differences between them ; it reveals the poetic kinship between Shijing and Han yuefu; it evaluates the significance of the common people’s compositions; and it displays the unique artistic value and cultural influence of Chinese early folk songs. ii Acknowledgments I would like to express my sincere gratitude to my supervisor Professor Graham Sanders for his supervision, inspirations, and encouragements during my two years M.A study in the Department of East Asian Studies at University of Toronto. -

Analysi of Dream of the Red Chamber

MULTIPLE AUTHORS DETECTION: A QUANTITATIVE ANALYSIS OF DREAM OF THE RED CHAMBER XIANFENG HU, YANG WANG, AND QIANG WU A bs t r a c t . Inspired by the authorship controversy of Dream of the Red Chamber and the applica- tion of machine learning in the study of literary stylometry, we develop a rigorous new method for the mathematical analysis of authorship by testing for a so-called chrono-divide in writing styles. Our method incorporates some of the latest advances in the study of authorship attribution, par- ticularly techniques from support vector machines. By introducing the notion of relative frequency as a feature ranking metric our method proves to be highly e↵ective and robust. Applying our method to the Cheng-Gao version of Dream of the Red Chamber has led to con- vincing if not irrefutable evidence that the first 80 chapters and the last 40 chapters of the book were written by two di↵erent authors. Furthermore, our analysis has unexpectedly provided strong support to the hypothesis that Chapter 67 was not the work of Cao Xueqin either. We have also tested our method to the other three Great Classical Novels in Chinese. As expected no chrono-divides have been found. This provides further evidence of the robustness of our method. 1. In t r o du c t ion Dream of the Red Chamber (˘¢â) by Cao Xueqin (˘»é) is one of China’s Four Great Classical Novels. For more than one and a half centuries it has been widely acknowledged as the greatest literary masterpiece ever written in the history of Chinese literature. -

Making the Palace Machine Work Palace Machine the Making

11 ASIAN HISTORY Siebert, (eds) & Ko Chen Making the Machine Palace Work Edited by Martina Siebert, Kai Jun Chen, and Dorothy Ko Making the Palace Machine Work Mobilizing People, Objects, and Nature in the Qing Empire Making the Palace Machine Work Asian History The aim of the series is to offer a forum for writers of monographs and occasionally anthologies on Asian history. The series focuses on cultural and historical studies of politics and intellectual ideas and crosscuts the disciplines of history, political science, sociology and cultural studies. Series Editor Hans Hågerdal, Linnaeus University, Sweden Editorial Board Roger Greatrex, Lund University David Henley, Leiden University Ariel Lopez, University of the Philippines Angela Schottenhammer, University of Salzburg Deborah Sutton, Lancaster University Making the Palace Machine Work Mobilizing People, Objects, and Nature in the Qing Empire Edited by Martina Siebert, Kai Jun Chen, and Dorothy Ko Amsterdam University Press Cover illustration: Artful adaptation of a section of the 1750 Complete Map of Beijing of the Qianlong Era (Qianlong Beijing quantu 乾隆北京全圖) showing the Imperial Household Department by Martina Siebert based on the digital copy from the Digital Silk Road project (http://dsr.nii.ac.jp/toyobunko/II-11-D-802, vol. 8, leaf 7) Cover design: Coördesign, Leiden Lay-out: Crius Group, Hulshout isbn 978 94 6372 035 9 e-isbn 978 90 4855 322 8 (pdf) doi 10.5117/9789463720359 nur 692 Creative Commons License CC BY NC ND (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0) The authors / Amsterdam University Press B.V., Amsterdam 2021 Some rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, any part of this book may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise). -

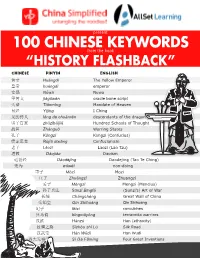

100 Chinese Keywords

present 100 CHINESE KEYWORDS from the book “HISTORY FLASHBACK” Chinese Pinyin English 黄帝 Huángdì The Yellow Emperor 皇帝 huángdì emperor 女娲 Nǚwā Nuwa 甲骨文 jiǎgǔwén oracle bone script 天命 Tiānmìng Mandate of Heaven 易经 Yìjīng I Ching 龙的传人 lóng de chuánrén descendants of the dragon 诸子百家 zhūzǐbǎijiā Hundred Schools of Thought 战国 Zhànguó Warring States 孔子 Kǒngzǐ Kongzi (Confucius) 儒家思想 Rújiā sīxiǎng Confucianism 老子 Lǎozǐ Laozi (Lao Tzu) 道教 Dàojiào Daoism 道德经 Dàodéjīng Daodejing (Tao Te Ching) 无为 wúwéi non-doing 墨子 Mòzǐ Mozi 庄子 Zhuāngzǐ Zhuangzi 孟子 Mèngzǐ Mengzi (Mencius) 孙子兵法 Sūnzǐ Bīngfǎ (Sunzi’s) Art of War 长城 Chángchéng Great Wall of China 秦始皇 Qín Shǐhuáng Qin Shihuang 妃子 fēizi concubines 兵马俑 bīngmǎyǒng terracotta warriors 汉族 Hànzú Han (ethnicity) 丝绸之路 Sīchóu zhī Lù Silk Road 汉武帝 Hàn Wǔdì Han Wudi 四大发明 Sì Dà Fāmíng Four Great Inventions Chinese Pinyin English 指南针 zhǐnánzhēn compass 火药 huǒyào gunpowder 造纸术 zàozhǐshù paper-making 印刷术 yìnshuāshù printing press 司马迁 Sīmǎ Qiān Sima Qian 史记 Shǐjì Records of the Grand Historian 太监 tàijiàn eunuch 三国 Sānguó Three Kingdoms (period) 竹林七贤 Zhúlín Qīxián Seven Bamboo Sages 花木兰 Huā Mùlán Hua Mulan 京杭大运河 Jīng-Háng Dàyùnhé Grand Canal 佛教 Fójiào Buddhism 武则天 Wǔ Zétiān Wu Zetian 四大美女 Sì Dà Měinǚ Four Great Beauties 唐诗 Tángshī Tang poetry 李白 Lǐ Bái Li Bai 杜甫 Dù Fǔ Du Fu Along the River During the Qingming 清明上河图 Qīngmíng Shàng Hé Tú Festival (painting) 科举 kējǔ imperial examination system 西藏 Xīzàng Tibet, Tibetan 书法 shūfǎ calligraphy 蒙古 Měnggǔ Mongolia, Mongolian 成吉思汗 Chéngjí Sīhán Genghis Khan 忽必烈 Hūbìliè Kublai -

Dreams of Timeless Beauties: a Deconstruction of the Twelve Beauties of Jinling in Dream of the Red Chamber and an Analysis of Their Image in Modern Adaptations

Dreams of Timeless Beauties: A Deconstruction of the Twelve Beauties of Jinling in Dream of the Red Chamber and an Analysis of Their Image in Modern Adaptations Xiaolu (Sasha) Han Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Prerequisite for Honors in East Asian Studies April 2014 ©2014 Xiaolu (Sasha) Han Acknowledgements First of all, I thank Professor Ellen Widmer not only for her guidance and encouragement throughout this thesis process, but also for her support throughout my time here at Wellesley. Without her endless patience this study would have not been possible and I am forever grateful to be one of her advisees. I would also like to thank the Wellesley College East Asian Studies Department for giving me the opportunity to take on such a project and for challenging me to expand my horizons each and every day Sincerest thanks to my sisters away from home, Amy, Irene, Cristina, and Beatriz, for the many late night snacks, funny notes, and general reassurance during hard times. I would also like to thank Joe for never losing faith in my abilities and helping me stay motivated. Finally, many thanks to my family and friends back home. Your continued support through all of my endeavors and your ability to endure the seemingly endless thesis rambles has been invaluable to this experience. Table of Contents INTRODUCTION ....................................................................................... 3 CHAPTER 1: THE PAIRING OF WOOD AND GOLD Lin Daiyu ................................................................................................. -

China (1750 –1918) Chinese Society Underwent Dramatic Transformations Between 1750 and 1918

Unit 2 Australia and Asia China (1750 –1918) Chinese society underwent dramatic transformations between 1750 and 1918. At the start of this period, China was a vast and powerful empire, dominating much of Asia. The emperor believed that China, as a superior civilisation, had little need for foreign contact. Foreign merchants were only permitted to trade from one Chinese port. By 1918, China was divided and weak. Foreign nations such as Britain, France and Japan had key trading ports and ‘spheres of influence’ within China. New ideas were spreading from the West, challenging Chinese traditions about education, the position of women and the right of the emperor to rule. chapter Source 1 An artist’s impression of Shanghai Harbour, C. 1875. Shanghai was one11 of the treaty ports established for British traders after China was defeated in the first Opium War (1839–42) 11A 11B 11C 11D What were the main features of What was the impact ofDRAFT How did the Chinese respond What was the situation in China Chinese society around 1750? Europeans on Chinese society to European influence? by 1918? 1 Chinese society was isolated from the rest of the from 1750 onwards? 1 The Chinese attempted to restrict foreign influence 1 By 1918, the Chinese emperor had been removed world, particularly the West. Suggest two possible and crush the opium trade, with little success. Why and a Chinese republic established in which the 1 One of the products that Western nations used, consequences of this isolation. do you think this was the case? nation’s leader was elected by the people. -

China's Last Great Classical Novel at the Crossroads Of

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Klaipeda University Open Journal Systems 176 RES HUMANITARIAE XIV ISSN 1822-7708 August Sladek – Flensburgo universiteto germanistikos prof. dr. pensininkas. Moksliniai interesai: matematinė lingvistika, lyginamoji filologija, filosofija, ontologija. Adresas: Landwehr 27, D-22087 Hamburgas, Vokietija. El. p.: [email protected]. August Sladek – retired professor of Germanistik, Univer- sity of Flensburg. Research interests: mathematical linguistics, comparative philology, philosophy, ontology. Address: Landwehr 27, D-22087 Hamburgas, Vokietija. El. p.: [email protected]. August Sladek University of Flensburg CHINA’S LAST GREAT CLASSICAL NOVEL AT THE CROSSROADS OF TRADITION AND MODERNIZATION1 Anotacija XVII a. viduryje parašytas „Raudonojo kambario sapnas“ yra naujausias iš Kinijos ketu- rių didžiųjų klasikos romanų. Tradicinių nusidavimų romanų kontekste jis apima daugybę pasakojimo būdų – realistinį, psichologinį, simbolinį, fantastinį. Parašytas kasdiene kalba (Pekino dialektu), jis tapo svarbus moderniosios, standartinės kinų kalbos (putong hua) formavimo šaltiniu naujojo kultūros judėjimo procese nuo praeito amžiaus 3-iojo dešim- tmečio. Mao Zeddongo labai vertinamam romanui komunistai bandė uždėti „progresyvų“ antspaudą. Romano paslėpta religinė (budizmo) intencija liko nepastebėta nei skaitytojų, nei religijotyrininkų. PAGRINDINIAI ŽODŽIAI: kinų literatūra, klasikinis romanas, tradicija ir modernumas. Abstract “The Red Chamber’s Dream” from the middle of 18th century is the youngest of Chi- nas “Four Great Classical Novels”. In the cloak of traditional story-telling it deploys a 1 Quotations from the novel as well as translations of names and terms are taken from Hawkes & Minford (1973–1986). References to their translation are given by the number of volume (Roman numerals) and of pages (Arabic numerals). -

Woodcut Illustrated Books in Late Imperial China: Visualisations of a Dream of Read Mansions

Woodcut Illustrated Books in Late Imperial China: Visualisations of A Dream of Read Mansions Kristína Janotová Lately, studies on the relationship between images and texts have increased exponentially. The reputation of book illustration as a minor art is rapidly being dissipated and images are being accepted as valuable material objects and epistemological cultural artefacts. Their research is extremely important for the evaluation of both images and texts. Therefore, the interaction between visual and textual images, their reception and interpretation have become topics in their own right. The connection between the art of the book and the method used for its printing has been close in all cultures in the world. The movable metal type in Europe, invented by the German Johannes Gutenberg around 1450, was cheap enough to replace woodblock printing for the reproduction of European texts. Book illustrations, however, were still produced through the woodblock printing method, which remained a major way to produce images in early modern European illustrated works. 1 While acknowledging the generally accepted originality of Gutenberg’s invention,2 the appearance of Chinese book illustra- tions, printed textiles and playing cards must have had a great impact on it. Since Chinese culture was regarded as a superior culture, Europeans borrowed some of its elements, at least until the end of the eighteenth century. For example, at the end of the 17th century, Louis XIV (1638–1715) and the Kangxi 康熙 Emperor 1 Donald F. Lach, Asia in the Making of Europe (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1979), 78. 2 Bi Sheng 畢 昇 (990–1051), an unsuccessful scholar hired by a printing house in Hangzhou, developed a printing method with movable type of hardened clay as early as the Northern Song dynasty. -

Popular Songs and Ballads of Han China

Popular Songs and Ballads of Han China Popular Songs and Ballads of Han China ANNE BIRRELL Open Access edition funded by the National Endowment for the Humanities / Andrew W. Mellon Foundation Humanities Open Book Program. Licensed under the terms of Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 In- ternational (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits readers to freely download and share the work in print or electronic format for non-commercial purposes, so long as credit is given to the author. Derivative works and commercial uses require per- mission from the publisher. For details, see https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. The Cre- ative Commons license described above does not apply to any material that is separately copyrighted. Open Access ISBNs: 9780824880347 (PDF) 9780824880354 (EPUB) This version created: 17 May, 2019 Please visit www.hawaiiopen.org for more Open Access works from University of Hawai‘i Press. © 1988, 1993 Anne Birrell All rights reserved To Hans H. Frankel, pioneer of yüeh-fu studies Acknowledgements I wish to thank The British Academy for their generous Fel- lowship which assisted my research on this book. I would also like to take this opportunity of thanking the University of Michigan for enabling me to commence my degree programme some years ago by awarding me a National Defense Foreign Language Fellowship. I am indebted to my former publisher, Mr. Rayner S. Unwin, now retired, for his helpful advice in pro- ducing the first edition. For this revised edition, I wish to thank sincerely my col- leagues whose useful corrections and comments have been in- corporated into my text. -

The Lyrics of Zhou Bangyan (1056-1121): in Between Popular and Elite Cultures

THE LYRICS OF ZHOU BANGYAN (1056-1121): IN BETWEEN POPULAR AND ELITE CULTURES by Zhou Huarao A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of East Asian Studies University of Toronto © Copyright by Zhou Huarao, 2014 The Lyrics of Zhou Bangyan (1056-1121): In between Popular and Elite Cultures Huarao Zhou Doctor of Philosophy Department of East Asian Studies University of Toronto 2014 Abstract Successfully synthesizing all previous styles of the lyric, or ci, Zhou Bangyan’s (1056-1121) poems oscillate between contrasting qualities in regard to aesthetics (ya and su), generic development (zheng and bian), circulation (musicality and textuality), and literary value (assumed female voice and male voice, lyrical mode and narrative mode, and the explicit and the implicit). These qualities emerged during the evolution of the lyric genre from common songs to a specialized and elegant form of art. This evolution, promoted by the interaction of popular culture and elite tradition, paralleled the canonization of the lyric genre. Therefore, to investigate Zhou Bangyan’s lyrics, I situate them within these contrasting qualities; in doing so, I attempt to demonstrate the uniqueness and significance of Zhou Bangyan’s poems in the development and canonization of the lyric genre. This dissertation contains six chapters. Chapter One outlines the six pairs of contrasting qualities associated with popular culture and literati tradition that existed in the course of the development of the lyric genre. These contrasting qualities serve as the overall framework for discussing Zhou Bangyan’s lyrics in the following chapters. Chapter Two studies Zhou Bangyan’s life, with a focus on how biographical factors shaped his perspective about the lyric genre. -

Nanyin Musical Culture in Southern Fujian, China : Adaptation and Continuity

Lim, Sau-Ping Cloris (2014) Nanyin musical culture in southern Fujian, China : adaptation and continuity. PhD Thesis. SOAS, University of London. http://eprints.soas.ac.uk/id/eprint/20292 Copyright © and Moral Rights for this PhD Thesis are retained by the author and/or other copyright owners. A copy can be downloaded for personal non‐commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This PhD Thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the copyright holder/s. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. When referring to this PhD Thesis, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the PhD Thesis must be given e.g. AUTHOR (year of submission) "Full PhD Thesis title", name of the School or Department, PhD PhD Thesis, pagination. NANYIN MUSICAL CULTURE IN SOUTHERN FUJIAN, CHINA: ADAPTATION AND CONTINUITY Sau-Ping Cloris Lim Volume 1: Main Text Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy 2014 Department of Music School of Oriental and African Studies University of London 1 DEDICATION Dedicated to the Heavenly Father DECLARATION 2 3 ABSTRACT This thesis is a study of the musical genre nanyin, one of the oldest and most prestigious living folk traditions preserved in southern Fujian (Minnan), China. As an emblem of Minnan ethnic identity, nanyin is still actively practised in the Southeast Asian Fujianese diaspora as well. Based on ethnographic investigations in Jinjiang County, this research explores multifaceted nanyin activities in the society at large.