NOTES for a HISTORY of CORAL FISHING and CORAL ARTEFACTS in MALTA1 Francesca Balzan* and Alan Deidun**

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Texts and Documents

MedicalHistory, 1977,21:182-186. Texts and Documents AN EIGHTEENTH-CENTURY BILL OF HEALTH OF THE ORDER OF ST. JOHN FROM MALTA by PAUL CASSAR* DURING iTS two hundred and sixty-eight years of domination over the Maltese Islands (1530-1798), the Order of St. John of Jerusalem waged an unceasing war against the Barbary and Turkish pirates in the Mediterranean. Those who escaped death were enslaved by the victor, irrespective of sex or age, or whether they were combatants or simply passengers and crews of unarmed vessels; so much so that slavery came to form a sort of institution regulated by definite rules concerning the selling, employment and ransoming of captives by either side. A Maltese boy, Gio Maria Zammit, was captured by the Barbary corsairs in 1734 at the age of fifteen years and sold as a slave at Tripoli in North Africa. After twelve years in captivity he renounced the Catholic faith and turned Moslem, as he was constrained to do by his master. He subsequently married a Moslem girl by whom he had several children. He finally succeeded in escaping from Tripoli after forty-three years in captivity, and reached Rome with his fourteen-year-old son Joseph. Gio Maria Zammit, by this time sixty-five years old, abjured the Moslem religion, became reconciled with the Catholic faith and had his son baptised in Rome. He eventually came with his son to Malta but being unable to find work, he decided to return to Rome in search of employment. In those days no one could leave Malta without the express permission of the Grand Court of the Castellania. -

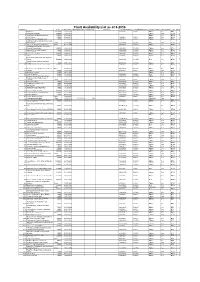

Sad Box 31/3 – Imports/Exports

March 2021 APPENDIX 15 SAD BOX 31/3 – IMPORTS/EXPORTS PORT OF LOADING CODES The information in this document is provided as a guide only and is not professional advice, including legal advice. It should not be assumed that the guidance is comprehensive or that it provides a definitive answer in every case. Appendix 15 - SAD Box 31/3 Port of Loading Codes March 2021 PORT OF LOADING CODES Code Port Name DEAAH1 Aachen NLAAM1 Aalsmeer FRABB1 Abbeville GBABA1 Aberaeron GBABD1 Aberdeen CIABJ1 Abidjan FITKU2 Abo (Turku) AEABU1 Abu al Bukhoosh AEAUH1 Abu Dhabi EGAKI1 Abu Kir EGAUE1 Abu Rudeis EGAZA1 Abu Zenima SVAQJ1 Acajutia GRACL1 Achladi ILACR1 Acre EGADA1 Adabiya TRADA1 Adana AUADL1 Adelaide YEADE1 Aden ESADR1 Adra MAAGA1 Agadir ESAGA1 Agaete GRAEF1 Agia Efimia GRAGM1 Agia Marina GRAPE1 Agia Pelagia GRAKI1 Agios Kirikos GRAKO1 Agios Konstantinos GRANI1 Agios Nikolaos Creta GRAGT1 Agio Theodoroi ESAGU1 Aguilas EGAIS1 Ain Sukhna FRAJA1 Ajaccio AEAJM1 Ajman TRAKB1 Akcaabat NLAKL1 Akersloot BGAKH1 Akhotopol CYAKT1 Akrotiri INALA1 Alang SBY USALB1 ALBANY NLABL1 Alblasserdam ESALD1 Alcudia IEALQ1 Alexandra Quay IEARO1 Alexandra Road Oil Page 2 of 35 Appendix 15 - SAD Box 31/3 Port of Loading Codes March 2021 Code Port Name ESALG1 Algeciras DZALG1 Alger ESALC1 Alicante NUALO1 ALOFI GRALO1 Alonissos EGAQU1 Al Qusayr NLAML1 Ameland GRAMF1 Amfiloxia GRAMI1 Amoliani NLAMS1 Amsterdam USANC1 Anchorage GRAND1 Andros DZAAE1 Annaba (Ex Bone) USANP1 Annapolis USARB1 Ann Arbor TWAPG1 An Ping TRAYT1 Antalya GRATK1 Antikyra GRANP1 Antiparos GRANT1 Antirio CLANF1 -

Treason's Harbour

Treason's Harbour Aubrey - Maturin Series BOOK NINE by Patrick O'Brian 'Smoothe runnes the Water, where the Brooke is deepe. And in his simple shew he harbours Treason.' Henry VI CHAPTER ONE A gentle breeze from the north-east after a night of rain, and the washed sky over Malta had a particular quality in its light that sharpened the lines of the noble buildings, bringing out all the virtue of the stone; the air too was a delight to breathe, and the city of Valletta was as cheerful as though it were fortunate in love or as though it had suddenly heard good news. This was more than usually remarkable in a group of naval officers sitting in the bowered court of Searle's hotel. To be sure, they looked out upon the arcaded Upper Baracca, filled with soldiers, sailors and civilians pacing slowly up and down in a sunlight so brilliant that it made even the black hoods the Maltese women wore look gay, while the officers' uniforms shone like splendid flowers. A cosmopolitan crowd, for although most of the colour was the scarlet and gold of the British army many of the nations engaged in the war against Napoleon were represented and the shell-pink of Kresimir's Croats, for example, made a charming contrast with the Neapolitan hussars' silver-laced blue. And then beyond and below the Baracca there was the vast sweep of the Grand Harbour, pure sapphire today, flecked with the sails of countless small craft plying between Valletta and the great fortified headlands on the other side, St Angelo and Isola, and the men-of-war, the troopships and the victuallers, a sight to please any sailor's heart. -

CALENDRIER CS 60025 • 85607 MONTAIGU CEDEX Tél

Pôle d’activités de la Bretonnière CALENDRIER CS 60025 • 85607 MONTAIGU CEDEX Tél. : 02 51 43 04 43 - Fax : 02 51 42 07 69 2019/2020 Email : [email protected] Site : www.globej.com 2019 2020 SEPTEMBRE OCTOBRE NOVEMBRE DÉCEMBRE JANVIER FÉVRIER 1 D 1 M 1 V TOUSSAINT 1 D 1 M JOUR DE L’AN 1 S 2 L 2 M 40 2 S 2 L 2 J 1 2 D 3 M 3 J 3 D 3 M 3 V 3 L 4 M 36 4 V 4 L 4 M 49 4 S 4 M 5 J 5 S 5 M 5 J 5 D 5 M 6 6 V 6 D 6 M 45 6 V 6 L 6 J 7 S 7 L 7 J 7 S 7 M 7 V 8 D 8 M 8 V 8 D 8 M 8 S 9 L 9 M 41 9 S 9 L 9 J 2 9 D 10 M 10 J 10 D 10 M 10 V 10 L 11 M 37 11 V 11 L ARMISTICE 18 11 M 50 11 S 11 M 12 J 12 S 12 M 12 J 12 D 12 M 7 13 V 13 D 13 M 46 13 V 13 L 13 J 14 S 14 L 14 J 14 S 14 M 14 V 15 D 15 M 15 V 15 D 15 M 15 S 16 L 16 M 42 16 S 16 L 16 J 3 16 D 17 M 17 J 17 D 17 M 17 V 17 L 18 M 38 18 V 18 L 18 M 51 18 S 18 M 19 J 19 S 19 M 19 J 19 D 19 M 8 20 V 20 D 20 M 47 20 V 20 L 20 J 21 S 21 L 21 J 21 S 21 M 21 V 22 D 22 M 22 V 22 D 22 M 22 S 23 L 23 M 43 23 S 23 L 23 J 4 23 D 24 M 24 J 24 D 24 M 52 24 V 24 L 25 M 39 25 V 25 L 25 M NOËL 25 S 25 M 26 J 26 S 26 M 26 J 26 D 26 M 9 27 V 27 D 44 27 M 48 27 V 27 L 27 J 28 S 28 L 28 J 28 S 28 M 28 V 29 D 29 M 29 V 29 D 29 M 5 29 S ZONE A : Académies : Besançon, Bordeaux, 30 L 30 M 30 S 30 L 30 J Clermont-Ferrand, Dijon, Grenoble, Limoges, Lyon, Poitiers ZONE B : Académies : Aix-Marseille, Amiens, Caen, 31 J 31 31 V Lille, Nancy-Metz, Nantes, Nice, Orléans-Tours, Reims, M Rennes, Rouen, Strasbourg ZONE C : Académies : Créteil, Montpellier, Paris, Toulouse, Versailles MARS AVRIL MAI JUIN JUILLET AOÛT 1 D 1 M 14 1 V FÊTE DU TRAVAIL 1 L L. -

43 Plenary Meeting Report of The

rd 43 PLENARY MEETING REPORT OF THE SCIENTIFIC, TECHNICAL AND ECONOMIC COMMITTEE FOR FISHERIES (PLEN-13-02) PLENARY MEETING, 8-12 July 2013, Copenhagen Edited by John Casey & Hendrik Doerner 2013 Report EUR 26094 EN European Commission Joint Research Centre Institute for the Protection and Security of the Citizen Contact information STECF secretariat Address: TP 051, 21027 Ispra (VA), Italy E-mail: [email protected] Tel.: 0039 0332 789343 Fax: 0039 0332 789658 https://stecf.jrc.ec.europa.eu/home http://ipsc.jrc.ec.europa.eu/ http://www.jrc.ec.europa.eu/ Legal Notice Neither the European Commission nor any person acting on behalf of the Commission is responsible for the use which might be made of this publication. This report does not necessarily reflect the view of the European Commission and in no way anticipates the Commission’s future policy in this area. Europe Direct is a service to help you find answers to your questions about the European Union Freephone number (*): 00 800 6 7 8 9 10 11 (*) Certain mobile telephone operators do not allow access to 00 800 numbers or these calls may be billed. A great deal of additional information on the European Union is available on the Internet. It can be accessed through the Europa server http://europa.eu/ JRC 83565 EUR 26094 EN ISBN 978-92-79-32531-1 ISSN 1831-9424 doi:10.2788/96228 Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union, 2013 © European Union, 2013 Reproduction is authorised provided the source is acknowledged How to cite this report: Scientific, Technical and Economic Committee for Fisheries (STECF) – 43rd Plenary Meeting Report (PLEN-13-02). -

Diaspora Entrepreneurial Networks, C. 1000 – 2000

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by OAR@UM THIRTEENTH INTERNATIONAL ECONOMIC HISTORY CONGRESS BUENOS AIRES 2002 SESSION X: DIASPORA ENTREPRENEURIAL NETWORKS, C. 1000 – 2000 The Maltese Entrepreneurial Networks from the seventeenth century onwards A review of the work done so far Carmel Vassallo University of Malta 1 Migration has been a feature of human existence since the very dawn of history. It has taken various forms and its intensity has varied over time. This century promises to be one of considerable population movements as a consequence of demographic changes presently underway. As populations in the ‘developed’ world plummet it is calculated that countries like Germany, for example, will have to import a million migrants of working age per year by the year 2020, as their own populations become older (The Economist 1 November 2001 Survey: The Next Society). But the clamour for workers from the business sector is often drowned by the opposition to migrants from other sections of society. When these migrant communities are from a markedly different cultural background, with a different religion, a different ethnicity and so on, the tensions can be even greater. Events like the 11 September 2001 and its aftermath have shown how these transnational communities are often percieved as threats to established lifestyles and state security, and potential sources of international terrorism. These transnational communities are often referred to as ethnic diasporas. The term ‘diaspora’, of Greek origin and meaning ‘dispersion’ or ‘scattering’, has come to refer to a very broad range of situations including: migrants in general; political, religious and other refugees and expellees; ethnic and racial minorities and aliens; and so on. -

Marsaxlokk Fishing Port & Its Local Fishing Community –Maritime

2019-3214-AJMS-MDT Marsaxlokk Fishing Port & its local Fishing 1 Community –Maritime Heritage and Practices in Times 2 of Change 3 4 Many tourists visit the various seaside destinations located along the coasts of the 5 Mediterranean every summer. Many of these places existed in the past as fishing 6 villages, including Marsaxlokk in Malta, which today is mentioned in the tourist 7 guides as one of Malta’s attractions offering local colour and history.In Malta, and 8 particularly in Marsaxlokk (a fishing village and the largest fishing harbour of 9 Malta), fishing has always been an integral part of the inhabitants’ life. Still today, 10 the Maltese fisheries are considered a type of Mediterranean artisanal activity, 11 operating multi-species and multi-gear fisheries, with fishers switching from one gear 12 to another several times a year, according to the fishing season. However, the tourist 13 and economic climate of the village is different from other seaside places we know in 14 the Mediterranean. Traditional fishing is dying out, and many artisanal fishermen 15 decide to resort to making money on the side as water taxis. This is caused by the 16 fatigue of long hours spent at sea, together with difficulties that did not exist in the 17 past in this territory: ecological problems like climate change, marine pollution and 18 overfishing. These local and regional problems- that other fishing communities in the 19 EU are facing and dealing with- do not encourage the young generation to follow 20 their parents’ way of life. The paper presents the process that the fishermen of 21 Marsaxlokk are undergoing in the context of social-economic change and tourists- 22 fishermen relations, and examines if the people there still practice the old ways of life 23 that characterize fishermen communities or if they have adopted a more commercial 24 approach, such as keeping themselves on the tourists’ destinations maps and finding 25 alternative or additional ways of living. -

Wars with the Barbary Powers, Volume IV Part 3

Naval Documents related to the United States Wars with the Barbary Powers Volume IV Part 3 of 3 Naval Operations including diplomatic background from April to September 6, 1804 United States Government Printing Office Washington, 1942 Electronically published by American Naval Records Society Bolton Landing, New York 2011 AS A WORK OF THE UNITED STATES FEDERAL GOVERNMENT THIS PUBLICATION IS IN THE PUBLIC DOMAIN. 328 NAVAL OPERATIONS, APRILSEPTEMBER 6, 1804 Extract from log book kept by Sailing Master Nathaniel Haraden, U. S. Navy, on board U. S. Frigate Conrtitution. Tuesday, 31 July 1804 Fresh Breezes from the Eastward with a rough Sea Stand' in for Tripoly (Squadron in company) under double reefed TO~S~S15 Courses - The Gun boats and Bombards are invariably continued in Tow by the Squadron - We condemned by survey 804 pounds of cheese Eotton, stinking & unfit for men to eat: the same was hove Overboard - At 1 P. M. we saw Tripoly bearing by compass S S E. We stood in for it till 4 P. M. when we wore to the Northc - The Bashaws Castle S E b S four Leagues - At this time strong breezes & cloudy weather. At 4 past 5 P. M. Tripoly S E b S S. 5 Leagues At 4 past 6 P. M. the wind shifted in a squall from East to N E b N - We sp[l]it the foresail from clew to Earing - In a few minutes after we split the Main Top sail - Unbent both & bent others - From this time till till 8 P. M. we were under a reef'd main- sail and close reefed fore topsail - At 7 down top gall! Yards; As the Gale is nearly dead on shore, it became necessary to press the ship which makes it hazardous in Towing the Gun boats & Bombards - At + past 9 handed the foretopsail; and set a reefed foresail At 10 Rove preventer tacks & sheets - by this time the gale had shifted by degrees to E B N - At Midnight strong gales from the Eastward. -

Malta and Sicily: Miscellaneous Research Projects Edited by Anthony Bonanno

! " # # $% & ' ( ) * *+ , (- . / 0+ 1 ! 2 *3 1 4 ! - * + # " # $ % % & #' ( ) % $ & *! !# + ( ,& - %% . &/ % 0 ( 0 # $ . # . - ( 1 . # . - # # . 2% . % # ( 5 3 # # )# )))' ( % . $ 4 # !5 4 ( *! !#+. ( $ . 1 # 6. 3 ( 3 7- 08 ( 2 . 3 %# !( 5 . +(9 # 3 3 . #.# ( # .:0 ( . !(* ;9<!+ % 4 . ## ( & ! % ! /: # 74 =33 8.0 78.: 7" 8.: # 7 !8 ,30 74>$8( % ! $ #. # ( 0 3 %.3 . $ (## . 3 3% 3 # ( 3 3 7% 83 % 3 # #3 ( 3 # # 3$ 3 (? . 3% ( ! . . ( # # ) #3 ;! 0 @9, #%# # A &((+ ## . .% (% . 0 . # (; ) 3 3 3 # ( . #. 3 3 # #% # ( !"! #$ % ! 43 % ## 3 3 73 8( " #. 3 %! 3 % . . % % ( . 3 # ( 00:> ! 9B;C .< # ## . +D ( % #. % # ! 3 # 3 . 3 ( 2 % # . 3 , 1 # A&( 0 > 3 3 (? ! . 3 2 2 %( )9BE93! ??(F.33 0 # 6(G% . %2 % 3 3 3 # 4 2 % 5 4 ) 5 4 % # 09< #( % 3 %(3# 3 % 4 (E % # 9 -

REPORT for Biennial Period, 2006-07 PART II (2007)

INTERNATIONAL COMMISSION for the CONSERVATION of ATLANTIC TUNAS R E P O R T for biennial period, 2006-07 PART II (2007) - Vol. 1 English version COM MADRID, SPAIN 2008 FOREWORD The Chairman of the International Commission for the Conservation of Atlantic Tunas presents his compliments to the Contracting Parties of the International Convention for the Conservation of Atlantic Tunas (signed in Rio de Janeiro, May 14, 1966), as well as to the Delegates and Advisers that represent said Contracting Parties, and has the honor to transmit to them the "Report for the Biennial Period, 2006-2007, Part II (2007)", which describes the activities of the Commission during the second half of said biennial period. This issue of the Biennial Report contains the Report of the 20th Regular Meeting of the Commission (Antalya, Turkey, November 9-18, 2007) and the reports of all the meetings of the Panels, Standing Committees and Sub- Committees, as well as some of the Working Groups. It also includes a summary of the activities of the Secretariat and a series of Annual Reports of the Contracting Parties of the Commission and Observers, relative to their activities in tuna and tuna-like fisheries in the Convention area. The Report for 2007 has been published in three volumes. Volume 1 includes the Secretariat’s Administrative and Financial Reports, the Proceedings of the Commission Meetings and the reports of all the associated meetings (with the exception of the Report of the Standing Committee on Research and Statistics-SCRS). Volume 2 contains the Secretariat’s Report on Statistics and Coordination of Research and the Report of the Standing Committee on Research and Statistics (SCRS) and its appendices. -

Covid-19) Supply / Port Restrictions

CORONAVIRUS (COVID-19) SUPPLY / PORT RESTRICTIONS EDITED 2021, SEPTEMBER 28 CORONAVIRUS (COVID-19) - SUPPLY / PORT RESTRICTIONS In order to respond to the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic, a number of governments and port authorities have issued entry/port restrictions. We are frequently updating our International Port Directory (IPD) information to help provide awareness on the changing supply restrictions by country/port. Each Port has been updated with one of the following color status: SUSPENDED SUBJECT TO INQUIRY NO RESTRICTION Deliveries are not possible. Deliveries are subject to inquiry. Continued supply. Contact your Customer Service Contact your Customer Service Please remain in close contact Officer to discuss options. Officer to discuss options. with your Customer Service Officer as the situation may change at short notice. Information on the Ports list will be updated on a daily basis with the latest information from the relevant authorities. Please note that this information should be used as a guide only to help interpret the local situation, and port restrictions may change at short notice and at any time. Information is provided in good faith, and is deemed to be correct at the time it is published. Customers should refer to the latest information published by the government of their destination country. For any questions, please contact your local Customer Service Officer. CORONAVIRUS (COVID-19) SUPPLY / PORT RESTRICTIONS 2 EDITED 2021, SEPTEMBER 28 SUPPLY RESTRICTIONS BY COUNTRY IMBITUBA ANGOLA CABINDA LUANDA SOYO ARGENTINA -

Chart Availability List As of 8-2016

Chart Availability List as of 8-2016 Number Title Scale Edition Date Withdrawn Date Replaced By Replaces Last NM Number Last NM Week-Year Product Status ARCS Chart Folio Disk 2 British Isles 1500000 23.07.2015 325\2016 2-2016 Edition Yes BF6 2 3 Chagos Archipelago 360000 21.06.2012 - Edition Yes BF38 5 5 `Abd Al Kuri to Suqutra (Socotra) 350000 07.03.2013 - Edition Yes BF32 5 6 Gulf of Aden 750000 26.04.2012 124\2015 1-2015 Edition Yes BF32 5 7 Aden Harbour and Approaches 25000 31.10.2013 452\2016 3-2016 Edition Yes BF32 5 La Skhirra-Gabes and Ghannouch with 9 Approaches Plans 24.10.1986 1578\2014 14-2014 New Yes BF24 4 11 Jazireh-Ye Khark and Approaches Plans 03.12.2009 4769\2015 37-2015 Edition Yes BF40 5 Al Aqabah to Duba and Ports on the 12 Coast of Saudi Arabia 350000 14.04.2011 101\2015 53-2015 Edition Yes BF32 5 13 Approaches to Cebu Harbour 35000 21.04.2011 3428\2014 31-2014 Edition Yes BF58 6 14 Cebu Harbour 12500 17.01.2013 4281P\2015 33-2015 Edition Yes BF58 6 15 Approaches to Jizan 200000 17.07.2014 105\2015 53-2015 Edition Yes BF32 5 16 Jizan 30000 19.05.2011 101\2015 53-2015 Edition Yes BF32 5 Plans of the Santa Cruz and Adjacent 17 Islands 500000 14.08.1992 2829\1995 33-1995 New Yes BF68 7 Falmouth Inner Harbour Including 18 Penryn 5000 20.02.2014 5087\2015 40-2015 Edition Yes BF1 1 20 Ile d'Ouessant to Pointe de la Coubre 500000 22.08.2013 419\2016 2-2016 Edition Yes BF16 1 26 Harbours on the South Coast of Devon Plans 17.04.2014 5726\2015 45-2015 Edition Yes BF1 1 27 Bushehr 25000 15.07.2010 984\2016 7-2016 Edition Yes