1. Off for Mesopotamia 2

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Palmyrene Prosopography

THE PALMYRENE PROSOPOGRAPHY by Palmira Piersimoni University College London Thesis submitted for the Higher Degree of Doctor of Philosophy London 1995 C II. TRIBES, CLANS AND FAMILIES (i. t. II. TRIBES, CLANS AND FAMILIES The problem of the social structure at Palmyra has already been met by many authors who have focused their interest mainly to the study of the tribal organisation'. In dealing with this subject, it comes natural to attempt a distinction amongst the so-called tribes or family groups, for they are so well and widely attested. On the other hand, as shall be seen, it is not easy to define exactly what a tribe or a clan meant in terms of structure and size and which are the limits to take into account in trying to distinguish them. At the heart of Palmyrene social organisation we find not only individuals or families but tribes or groups of families, in any case groups linked by a common (true or presumed) ancestry. The Palmyrene language expresses the main gentilic grouping with phd2, for which the Greek corresponding word is ØuAi in the bilingual texts. The most common Palmyrene formula is: dynwpbd biiyx... 'who is from the tribe of', where sometimes the word phd is omitted. Usually, the term bny introduces the name of a tribe that either refers to a common ancestor or represents a guild as the Ben Komarê, lit. 'the Sons of the priest' and the Benê Zimrâ, 'the sons of the cantors' 3 , according to a well-established Semitic tradition of attaching the guilds' names to an ancestor, so that we have the corporations of pastoral nomads, musicians, smiths, etc. -

Stratigraphy ﺔ ـــــــ ـــــ ـــــ اﻟطﺑﺎﻗﯾ

Iraqi Bull. Geol. Min. Special Issue, 2007: Geology of Iraqi Western Desert p 51 124 STRATIGRAPHY Varoujan K. Sissakian * and Buthaina S. Mohammed ** ABSTRACT The stratigraphy of the Iraqi Western Desert is reviewed. The oldest exposed rocks are Permian in age, belong to the Ga`ara Formation, whereas the youngest are Pliocene – Pleistocene, belong to the Zahra Formation. The exposed stratigraphical column is represented by 32 formations. Morover, eight main types of Quaternary deposits, which have wide geographic extent are reviewed too. For each exposed formation, the exposure areas, subsurface extension, main lithology as described inform of members and/ or informal units, thickness, fossils, age, depositional environment and the lower contact is described. Because, almost all formations are described by different authors from different localities, therefore all descriptions of different authors are reviewed, with occasional comments.The paleogeography is reviewed briefly. Each formation is discussed, for majority of them the present author`s opinion are given, with many recommendations for future studies. Some new ideas dealing with many aspects for many formations including proposals for establishing new formations are given, too. الطباقيـــــــــــــــــة فاروجان خاجيك سيساكيان* و بثينة سلمان محمد** المستخلص تمت مراجعة طباقية الصحراء الغربية العراقية من اقدم الصخور المتكشفة والتي تعود الى عصرالبيرمي المتمثلة بتكوين الكعرة والى عصر البﻻيوسين – البﻻيستوسين المتمثلة بتكوين الزھرة. ان العمود الطباقي في الصحراء الغربية العراقية يتمثل باثنين وثﻻثين تكوين متكشف، اضافة الى ثمانية انواع رئيسية من ترسبات العصر الرباعي ذات اﻹمتداد الجغرافي الواسع والسمك الكبير. لكل تكوين متكشف، تم وصف التوزيع الجغرافي السطحي وتحت السطحي، الصخارية وكما جاء في وصف كل عضو او وحدة في التكوين، السمك، المتحجرات، العمر، البيئة الترسيبية والحد اﻻسفل. -

Wasia Aquifer

Chapter 13 Sakaka-Rutba Wasia-Biyadh- Aruma Aquifer System (North) INVENTORY OF SHARED WATER RESOURCES IN WESTERN ASIA (ONLINE VERSION) How to cite UN-ESCWA and BGR (United Nations Economic and Social Commission for Western Asia; Bundesanstalt für Geowissenschaften und Rohstoffe). 2013. Inventory of Shared Water Resources in Western Asia. Beirut. CHAPTER 13 - WASIA-BIYADH-ARUMA AQUIFER SYSTEM (NORTH): SAKAKA-RUTBA Wasia-Biyadh-Aruma Aquifer System (North) Sakaka-Rutba EXECUTIVE SUMMARY BASIN FACTS The Wasia-Biyadh-Aruma Aquifer System RIPARIAN COUNTRIES Iraq, Saudi Arabia (North) lies on a high plain (400-800 m) that Iraq: Rutba-Ms’ad-Hartha-Tayarat extends across the western Rutba High in Iraq ALTERNATIVE NAMES and the Widyan Plain in Saudi Arabia. Also Saudi Arabia: Wasia Group Sakaka-Aruma referred to as Sakaka-Rutba, the Wasia-Biyadh- RENEWABILITY Very low to low (0-20 mm/yr) Aruma Aquifer System (North) constitutes an important aquifer system in the area with HYDRAULIC LINKAGE Weak freshwater flowing through six aquiferous WITH SURFACE WATER units (Rutba-Ms’ad-Hartha-Tayarat in Iraq and Sakaka-Aruma in Saudi Arabia). Exploitation ROCK TYPE Mixed depth ranges between 200 and 400 m bgl. Unconfined at/near outcrop areas AQUIFER TYPE Confined further away The use of this aquifer system is currently limited due to its remoteness and the harsh EXTENT ~112,000 km2 environment in the area but the towns of Ar’ar AGE Mesozoic (Middle to Late Cretaceous) and Sakaka in Saudi Arabia and Rutba in Iraq presumably rely on the aquifer system for their Sandstones, locally calcareous or LITHOLOGY water supply. -

Baghdad to Damascus Viâ El Jauf, Northern Arabia Author(S): S

Baghdad to Damascus viâ El Jauf, Northern Arabia Author(s): S. S. Butler Source: The Geographical Journal, Vol. 33, No. 5 (May, 1909), pp. 517-533 Published by: geographicalj Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/1777081 Accessed: 27-06-2016 01:14 UTC Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at http://about.jstor.org/terms JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Wiley, The Royal Geographical Society (with the Institute of British Geographers) are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The Geographical Journal This content downloaded from 137.99.31.134 on Mon, 27 Jun 2016 01:14:42 UTC All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms The Geographical Journal. No. 5. MAY, 1909. VOL. XXXII. BAGHDAD TO DAMASCUS VIA EL JAUF, NORTHERN ARABIA.* By Captain S. S. BUTLER. THE leave of Captain Aylmer and myself from East Africa falling due about the same time last autumn (1907), we decided, if possible, to try to return to England vid the Persian gulf, Baghdad, and Damascus; but, instead of following the usual route from Baghdad to Damascus along the Euphrates, we intended to try to go south-west from Baghdad to El Jauf,f which is situated in North Central Arabia, on the northern edge of the great Nefud (or sandy desert), and from there go up north- west, eventually coming out at Damascus by way of the Jebel Hauran. -

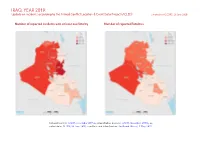

IRAQ, YEAR 2019: Update on Incidents According to the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) Compiled by ACCORD, 23 June 2020

IRAQ, YEAR 2019: Update on incidents according to the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) compiled by ACCORD, 23 June 2020 Number of reported incidents with at least one fatality Number of reported fatalities National borders: GADM, November 2015a; administrative divisions: GADM, November 2015b; in- cident data: ACLED, 20 June 2020; coastlines and inland waters: Smith and Wessel, 1 May 2015 IRAQ, YEAR 2019: UPDATE ON INCIDENTS ACCORDING TO THE ARMED CONFLICT LOCATION & EVENT DATA PROJECT (ACLED) COMPILED BY ACCORD, 23 JUNE 2020 Contents Conflict incidents by category Number of Number of reported fatalities 1 Number of Number of Category incidents with at incidents fatalities Number of reported incidents with at least one fatality 1 least one fatality Explosions / Remote Conflict incidents by category 2 1282 452 1253 violence Development of conflict incidents from 2016 to 2019 2 Protests 845 12 72 Battles 719 541 1735 Methodology 3 Riots 242 72 390 Conflict incidents per province 4 Violence against civilians 191 136 240 Strategic developments 190 6 7 Localization of conflict incidents 4 Total 3469 1219 3697 Disclaimer 7 This table is based on data from ACLED (datasets used: ACLED, 20 June 2020). Development of conflict incidents from 2016 to 2019 This graph is based on data from ACLED (datasets used: ACLED, 20 June 2020). 2 IRAQ, YEAR 2019: UPDATE ON INCIDENTS ACCORDING TO THE ARMED CONFLICT LOCATION & EVENT DATA PROJECT (ACLED) COMPILED BY ACCORD, 23 JUNE 2020 Methodology on what level of detail is reported. Thus, towns may represent the wider region in which an incident occured, or the provincial capital may be used if only the province The data used in this report was collected by the Armed Conflict Location & Event is known. -

ISIS in 2018

REPORT Hisham al-Hashimi ISIS in 2018 Iraq as a Model 10 - 2018 Hisham al-Hashimi: Fellow of the Security, Defence and Counterterrorism Program at the Centre of Making Policy for International and Strategic Studies. He is also a strategic expert in security and extremist groups, and the author of Alem Daesh (The World of Daesh). The Centre of Making Policy for International and Strategic Studies: The Centre of Making Policy for International and Strategic Studies is an independent research institute that collaborates with an excellent group of experts and researchers in various fields, namely, politics, economics and social studies. The Centre provides a range of strategic analyses of the events in the Middle East and North Africa, with a special focus on Iraq, and attempts to provide decision-making circles with enriching alternatives. Istanbul - Turkey Email: [email protected] Introduction to the Formation of ISIS: Since October 2010, ISIS has gone through four stages: • 2010: formation of solid nucleus around al-Baghdadi • 2013: Declaration of the unification of Iraq and Sham sections and separation from al-Qaeda • 2014: Breaking the borders, declaration of allegiance to the Caliphate of al-Baghdadi and the designation of the borders of the land of Caliphate and empowerment. • In 2015, the start of the battles of liberation from ISIS occupation in Ard al-Tamkeen (land of empowerment) until the end of 2017, when it declared its complete defeat in Iraq, 98% of Syria, 97% of Libya and 98% of Sinai. Four years ago, the International Coalition announced that it had eliminated ISIS’s military capabilities, expelled it from densely-populated cities and villages, hindered the influx of foreign combatants to the land of battles, and then hindered the reverse return, drained terrorism’s financial sources from fixed capital and movable assets, decoded ISIS’s administration and finance, eliminated the staff of the central chamber of finance and zakat and targeted the centres of ISIS’s military and chemical development and manufacturing centres. -

Palmyrena. Settlements, Forts and Nomadic Networks

7 Palmyrena. Settlements, Forts and Nomadic Networks Jørgen Christian Meyer The French archaeologist Daniel Schlumberger was terns.4 The main source of water was cisterns, which THE SC I.D A N .H . ROYAL the first scholar to carry out investigations outside the could be seen in large numbers in the landscape and DANISH oasis Palmyra.1 1933 - 1935 made in the sites.5 of 23From he surveys relation to 4 • and excavations in the mountainous area north-west Schlumberger did not excavate the ordinary build Ü • ACADEMY of Palmyra, and the results were published in his pio ings; but the places of worship were investigated in THE neer work La Palmyrene du nord-ouest. Villages et lieux de culte detail.6 The shrines were of different shapes and sizes WORLD OF de l’époque imperiale. Recherches archéologiques sur la mise en and more solidly built with larger stones and blocks.7 SCIENCES OF valeur d’une region du desert par les Palmyréniens from 1951. The smallest ones are simple structures, only measur PALMYRA For the first time archaeological data were available ing about 6x4 meters. At other sites, some shrines are AND for a discussion of the relationship between the oasis part of a larger group of buildings with banquet LETTERS city and the surrounding territory. halls.8 Many of the shrines and altars were adorned with inscriptions and li • Schlumberger excavated 15 settlements primarily dedicatory reliefs, showing 2 0 l 6 in the northern part of the Jebel Chaar tableland ons, mounted horsemen and deities. The Arabian god about 50 km north-west of the oasis (fig. -

Attachment - 11 List of Important Bird Areas

Attachment - 11 List of Important Bird Areas Coordinates Site No. Site Name Latitude (N) Longitude (E) 001 Benavi 37 20 43 25 002 Dori Serguza 37 20 43 30 003 Ser Amadiya 37 10 43 22 004 Bakhma, Dukan and Darbandikhan dams 36 10 44 55 005 Huweija marshes 35 15 43 50 006 Anah and Rawa 34 32 41 55 007 Mahzam and Lake Tharthar 34 20 43 22 008 Samara dam 34 15 43 50 009 Abu Dalaf and Shari lake 34 15 44 00 010 Augla, Wadi Hauran 33 55 41 02 011 Baquba wetlands 33 55 44 50 012 Gasr Muhaiwir, Wadi Hauran 33 33 41 14 013 Attariya plains 33 25 44 55 014 Abu Habba 33 20 44 20 015 Al Jadriyah and Umm Al Khanazeer island 33 20 44 24 016 Haur Al Habbaniya and Ramadi marshes 33 16 43 30 017 Haur Al Shubaicha 33 15 45 18 018 Al Musayyib - Haswa area 32 48 44 17 019 Hindiya barrage 32 42 44 17 020 Haur Al Suwayqiyah 32 42 45 55 021 Bahr Al Milh 32 40 43 40 022 Haur Al Abjiya and Umm Al Baram 32 28 46 05 023 Haur Delmaj 32 20 45 30 024 Haur Sarut 32 19 46 46 025 Haur Al Sa'adiyah 32 10 46 38 026 Haur Ibn Najim 32 08 44 35 027 Haur Al Hachcham and Haur Maraiba 32 05 46 12 028 Haur Al Haushiya 32 05 46 54 029 Shatt Al Gharraf 31 57 46 00 030 Haur Chubaisah area 31 56 47 20 031 Haur Sanniya 31 55 46 48 032 Haur Om am Nyaj 31 45 47 25 1 Coordinates Site No. -

Tribes, State, and Technology Adoption in Arid Land Management, Syria

CAPRi WORKING PAPER NO. 15 TRIBES, STATE, AND TECHNOLOGY ADOPTION IN ARID LAND MANAGEMENT, SYRIA Rae, J, Arab, G., Nordblom, T., Jani, K., and Gintzburger, G. CGIAR Systemwide Program on Collective Action and Property Rights www.capri.cgiar.org Secretariat: International Food Policy Research Institute 2033 K Street, N.W. Washington, D.C. 20006 U.S.A. JUNE 2001 CAPRi Working Papers contain preliminary material and research results, and are circulated prior to a full peer review in order to stimulate discussion and critical comment. It is expected that most Working Papers will eventually be published in some other form, and that their content may also be revised. ABSTRACT Arid shrub-lands in Syria and elsewhere in West Asia and North Africa are widely thought degraded. Characteristic of these areas is a preponderance of unpalatable shrubs or a lack of overall ground cover with a rise in the associated risks of soil erosion. Migrating pastoralists have been the scapegoats for this condition of the range. State steppe interventions of the last forty years have reflected this with programs to supplant customary systems with structures and institutions promoting western grazing systems and technologies. Principal amongst the latter has been shrub technology, particularly Atriplex species, for use in land rehabilitation and as a fodder reserve. This paper deconstructs state steppe policy in Syria by examining the overlap and interface of government and customary legal systems as a factor in the history of shrub technology transfer in the Syrian steppe. It is argued that the link made between signs of degradation and perceived moribund customary systems is not at all causal. -

Deformational Style of the Soft Sediment (SEISMITES) Within the Uppermost Part of the Euphrates Formation, Western Iraq

Journal of Earth Sciences and Geotechnical Engineering, vol. 4, no. 4, 2014, 71-86 ISSN: 1792-9040 (print), 1792-9660 (online) Scienpress Ltd, 2014 Deformational Style of the Soft Sediment (SEISMITES) within the Uppermost Part of the Euphrates Formation, Western Iraq Varoujan K. Sissakian1, Saffa F. Fouad2, Nadhir Al-Ansari3and Sven Knutsson4 Abstract The Euphrates Formation (Early Miocene) is wide spread formations in central western part of Iraq. It consists of basal conglomerate, well bedded, grey, fossiliferous and hard limestones (Lower Member), chalky like dolomitic limestone, white and massive, green marl, and deformed, brecciated dolomitic limestone and well bedded undulated limestone (Upper Member). The thickness of the formation Iraq is 35-110 m. The uppermost part of the Euphrates Formation includes Brecciated Unit. The fragments (size 1 – 3 cm) are semi angular to semi rounded, consist of very finely crystalline, silicified limestone, arranged in systematic form, which is parallel to the deformations and undulations that are present in both the brecciated mass and the overlying Undulated Limestone Unit. These characteristics of the fragments indicate that the breccia is not formed due to break in sedimentation, but it is syn-sedimentary breccia. The genesis and deformation style of the breccia is discussed in this study. The results indicate the seismic effect on the development of the breccia, during the deposition, which means syn-sedimentary origin of the breccia, most probably due to tectonic unrest, which has caused seismic shocks in the depositional area; such sediments are called "seismites". Keywords: Euphrates Formation, Earthquake, Deformation, Undulation, Seismite, Iraq 1 Introduction The Euphrates Formation (Early Miocene) is widely exposed in the central western part of Iraq [1, 2] (Figure1). -

Map 21A Latest Campanian HST to K180

Van Golu Kiran MALTEPE 38°E WEST 40°ESARICAK YENIKOY EAST Budak 42°E 44°E 46°E 48°E 50°E 52°E KATIN KURKAN YATIR YENIKOY Hazro N SOUTH Hazro-1 & 2 Hezan Handof-1 Divana Silvan-1 38°N KURKAN BARBES Hazro S Kmbosdag Korudag Katin-1 SELMO 38°N CELIKILI Indet BEYKAN KAYAKOY Doondag Indet MALTEPE Tayarat Formation Indet Indet O. Sungurlu-1/A Indet Kastel-1 SILIVANKA DODAN Caspian Indet Indet Indet ADIYAMAN Indet Indet Macfadyen (1938) pointed out the presence of a fish bed, in presumably Cretaceous sandy limestones, at Indet Indet Coskunsel-2 PIYANKO E. Kahta SAHABAN KURTALAN Tabriz Tut Adiyaman-8 Karakus-10 KAYAKOY WEST GERMIK Kavikadag-1 Gur Ayarat, where abundant teeth but fewer bone fragments and vertebrae were found (n67). Durukaynak-2 Cemberlitas-14 K. Akceli-1 Bucak-1 Diyarbakir Gölbasi Indet Sinan-1 Indet Siverek-1 Alidami Siirt Diagnostic fossils and age Fossils in the Tayarat Fm include: Loftusia morgani Douville and Ompahlocyclus Karakopru-1 Alidag-2 SEZGIN MAGRIP Besni-1 GARZAN Kentalan-7 macropora (Lamarck). According to H. A. Field and K.D.Jones (unpubl. data, 1958) the Tayarat LimestoneSea contains Terbüzek ADIYAMAN KAHTA Besikli-6 Daryacheh ye Orumiyeh Indet WEST RAMAN Kentalan-2 corals, rudists (including Eoradolites?), gastropods, lamellibranchs, and algae. They maintained that generic SOUTH identification is often difficult as most of the original structures have been destroyed by recrystallisation and Sahabe-1 Kahta-2 RAMAN K. Maras Indet some by dolomitisation. In addition to the fossils recognised in the type section, the following microfossils Indet have been determined from the subsurface sections: Lepidorbitoides socialis (Leymerie), Indet Gercus-1 Orbitoides media (d’Archiac), O. -

The Royal Engineers a Journal

The Royal Engineers a Journal. 00 , Camouflage in Nature and in War . Dr. H. B. Cott 501 ' The Military Engineer in Modern Warfare . Major-Gen. L. V. Bond 518 Construction of R.C.C. Bridges in the Field . Capt. W. F. Anderson 530 Field Survey . Capt. S. G. Hudsonj[ 535 y Coast Defences of 75 Years Ago Col. A. G. B. Buchanan 540 iA Desert Survey . Capt. D. W. Price 543 The French Emigrant Engineers . Major M. E. S. Laws 560 j Works Services and Engineer Training .Col. C. K.ing 566 Ideal Field Company Training or The Reconstruction of Eastriggs Depot Major B. C. Davey 572 Lydd Ranges . Lieut.-Col. T. T. Behrens 581 D Histories of the Infantry Battalions, Territorial Army (Continued) . 592 0 Overland to India, 1938 . Lieut. A. C. Lewis 602 Professional Note. Painting . 6 13 Memoirs. Correspondence. Books. Magazines . 616 VOL. LII. DECEMBER, 1938. CHATHAM: THE INSTITUTION OF ROYAL ENGINEERS. U TELEPHONE: CHATHAM 2669, Z AGBNTS AND PRINTERS: MACKAYS LTD. LONDON: HUGH REES, LTD., 5, REGENT STRBET, S.W.I. O All ,-^' . INSTITUTION OF RE OFFICE COPY H ; [- DO NOT REMOVE i II *0 9, EXPAMET EXPANDED METAL British Steel :: British Labour Reinforcement for Concrete With a proper combination of "Ex- pamet " Expanded Steel and Concrete, light thin slabbing is obtainable of great strength and fire-resistant efficiency; it effects a considerable reduction in dead-weight of super- structure and in vertical building height, and it is used extensively in any type of building-brick, steel, reinforced concrete, etc. "Expamet" ensures an even dis- tribution of stress throughout the concrete work: as all the strands or members are connected rigidly, they cannot be displaced by the laying and tamping of the concrete.