Heroes Fighting Snake Demons: Problems of Identification in Panjikent Paintings

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Eastern and Western Look at the History of the Silk Road

Journal of Critical Reviews ISSN- 2394-5125 Vol 7, Issue 9, 2020 EASTERN AND WESTERN LOOK AT THE HISTORY OF THE SILK ROAD Kobzeva Olga1, Siddikov Ravshan2, Doroshenko Tatyana3, Atadjanova Sayora4, Ktaybekov Salamat5 1Professor, Doctor of Historical Sciences, National University of Uzbekistan named after Mirzo Ulugbek, Tashkent, Uzbekistan. [email protected] 2Docent, Candidate of historical Sciences, National University of Uzbekistan named after Mirzo Ulugbek, Tashkent, Uzbekistan. [email protected] 3Docent, Candidate of Historical Sciences, National University of Uzbekistan named after Mirzo Ulugbek, Tashkent, Uzbekistan. [email protected] 4Docent, Candidate of Historical Sciences, National University of Uzbekistan named after Mirzo Ulugbek, Tashkent, Uzbekistan. [email protected] 5Lecturer at the History faculty, National University of Uzbekistan named after Mirzo Ulugbek, Tashkent, Uzbekistan. [email protected] Received: 17.03.2020 Revised: 02.04.2020 Accepted: 11.05.2020 Abstract This article discusses the eastern and western views of the Great Silk Road as well as the works of scientists who studied the Great Silk Road. The main direction goes to the historiography of the Great Silk Road of 19-21 centuries. Keywords: Great Silk Road, Silk, East, West, China, Historiography, Zhang Qian, Sogdians, Trade and etc. © 2020 by Advance Scientific Research. This is an open-access article under the CC BY license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/) DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.31838/jcr.07.09.17 INTRODUCTION another temple in Suzhou, sacrifices are offered so-called to the The historiography of the Great Silk Road has thousands of “Yellow Emperor”, who according to a legend, with the help of 12 articles, monographs, essays, and other kinds of investigations. -

Compare and Analyzing Mythical Characters in Shahname and Garshasb Nāmeh

WALIA journal 31(S4): 121-125, 2015 Available online at www.Waliaj.com ISSN 1026-3861 © 2015 WALIA Compare and analyzing mythical characters in Shahname and Garshasb Nāmeh Mohammadtaghi Fazeli 1, Behrooze Varnasery 2, * 1Department of Archaeology, Shushtar Branch, Islamic Azad University, Shushtar, Iran 2Department of Persian literature Shoushtar Branch, Islamic Azad University, Shoushtar Iran Abstract: The content difference in both works are seen in rhetorical Science, the unity of epic tone ,trait, behavior and deeds of heroes and Kings ,patriotism in accordance with moralities and their different infer from epic and mythology . Their similarities can be seen in love for king, obeying king, theology, pray and the heroes vigorous and physical power. Comparing these two works we concluded that epic and mythology is more natural in the Epic of the king than Garshaseb Nameh. The reason that Ferdowsi illustrates epic and mythological characters more natural and tangible is that their history is important for him while Garshaseb Nameh looks on the surface and outer part of epic and mythology. Key words: The epic of the king;.Epic; Mythology; Kings; Heroes 1. Introduction Sassanid king Yazdgerd who died years after Iran was occupied by muslims. It divides these kings into *Ferdowsi has bond thought, wisdom and culture four dynasties Pishdadian, Kayanids, Parthian and of ancient Iranian to the pre-Islam literature. sassanid.The first dynasties especially the first one Garshaseb Nameh has undoubtedly the most shares have root in myth but the last one has its roots in in introducing mythical and epic characters. This history (Ilgadavidshen, 1999) ballad reflexes the ethical and behavioral, trait, for 4) Asadi Tusi: The Persian literature history some of the kings and Garshaseb the hero. -

Dragon and the Phoenix Teacher's Notes.Indd

Usborne English The Dragon and the Phoenix • Teacher’s notes Author: traditi onal, retold by Lesley Sims Reader level: Elementary Word count: 235 Lexile level: 350L Text type: Folk tale from China About the story A dragon and a phoenix live on opposite sides of a magic river. One day they meet on an island and discover a shiny pebble. The dragon washes it and the phoenix polishes it unti l it becomes a pearl. Its brilliant light att racts the att enti on of the Queen of Heaven, and that night she sends a guard to steal it while the dragon and phoenix are sleeping. The next morning, the dragon and phoenix search everywhere and eventually see their pearl shining in the sky. They fl y up to retrieve it, but the pearl falls down and becomes a lake on the ground below. The dragon and the phoenix lie down beside the lake, and are sti ll there today in the guise of Dragon Mountain and Phoenix Mountain. The story is based on The Bright Pearl, a Chinese folk tale. Chinese dragons are typically depicted without wings (although they are able to fl y), and are associated with water and wisdom. Chinese phoenixes are immortal, and do not need to die and then be reborn. They are associated with loyalty and honesty. The dragon and phoenix are oft en linked to the male yin and female yang qualiti es, and in the past, a Chinese emperor’s robes would typically be embroidered with dragons and an empress’s with phoenixes. -

Curiosity Killed the Bird: Arbitrary Hunting of Harpy Eagles Harpia

Cotinga30-080617:Cotinga 6/17/2008 8:11 AM Page 12 Cotinga 30 Curiosity killed the bird: arbitrary hunting of Harpy Eagles Harpia harpyja on an agricultural frontier in southern Brazilian Amazonia Cristiano Trapé Trinca, Stephen F. Ferrari and Alexander C. Lees Received 11 December 2006; final revision accepted 4 October 2007 Cotinga 30 (2008): 12–15 Durante pesquisas ecológicas na fronteira agrícola do norte do Mato Grosso, foram registrados vários casos de abate de harpias Harpia harpyja por caçadores locais, motivados por simples curiosidade ou sua intolerância ao suposto perigo para suas criações domésticas. A caça arbitrária de harpias não parece ser muito freqüente, mas pode ter um impacto relativamente grande sobre as populações locais, considerando sua baixa densidade, e também para o ecossistema, por causa do papel ecológico da espécie, como um predador de topo. Entre as possíveis estratégias mitigadoras, sugere-se utilizar a harpia como espécie bandeira para o desenvolvimento de programas de conservação na região. With adult female body weights of up to 10 kg, The study was conducted in the municipalities Harpy Eagles Harpia harpyja (Fig. 1) are the New of Alta Floresta (09º53’S 56º28’W) and Nova World’s largest raptors, and occur in tropical forests Bandeirantes (09º11’S 61º57’W), in northern Mato from Middle America to northern Argentina4,14,17,22. Grosso, Brazil. Both are typical Amazonian They are relatively sensitive to anthropogenic frontier towns, characterised by immigration from disturbance and are among the first species to southern and eastern Brazil, and ongoing disappear from areas colonised by humans. fragmentation of the original forest cover. -

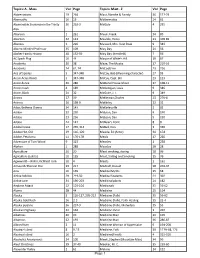

California Folklore Miscellany Index

Topics: A - Mass Vol Page Topics: Mast - Z Vol Page Abbreviations 19 264 Mast, Blanche & Family 36 127-29 Abernathy 16 13 Mathematics 24 62 Abominable Snowman in the Trinity 26 262-3 Mattole 4 295 Alps Abortion 1 261 Mauk, Frank 34 89 Abortion 22 143 Mauldin, Henry 23 378-89 Abscess 1 226 Maxwell, Mrs. Vest Peak 9 343 Absent-Minded Professor 35 109 May Day 21 56 Absher Family History 38 152-59 May Day (Kentfield) 7 56 AC Spark Plug 16 44 Mayor of White's Hill 10 67 Accidents 20 38 Maze, The Mystic 17 210-16 Accidents 24 61, 74 McCool,Finn 23 256 Ace of Spades 5 347-348 McCoy, Bob (Wyoming character) 27 93 Acorn Acres Ranch 5 347-348 McCoy, Capt. Bill 23 123 Acorn dance 36 286 McDonal House Ghost 37 108-11 Acorn mush 4 189 McGettigan, Louis 9 346 Acorn, Black 24 32 McGuire, J. I. 9 349 Acorns 17 39 McKiernan,Charles 23 276-8 Actress 20 198-9 McKinley 22 32 Adair, Bethena Owens 34 143 McKinleyville 2 82 Adobe 22 230 McLean, Dan 9 190 Adobe 23 236 McLean, Dan 9 190 Adobe 24 147 McNear's Point 8 8 Adobe house 17 265, 314 McNeil, Dan 3 336 Adobe Hut, Old 19 116, 120 Meade, Ed (Actor) 34 154 Adobe, Petaluma 11 176-178 Meals 17 266 Adventure of Tom Wood 9 323 Measles 1 238 Afghan 1 288 Measles 20 28 Agriculture 20 20 Meat smoking, storing 28 96 Agriculture (Loleta) 10 135 Meat, Salting and Smoking 15 76 Agwiworld---WWII, Richfield Tank 38 4 Meats 1 161 Aimee McPherson Poe 29 217 Medcalf, Donald 28 203-07 Ainu 16 139 Medical Myths 15 68 Airline folklore 29 219-50 Medical Students 21 302 Airline Lore 34 190-203 Medicinal plants 24 182 Airplane -

Research Article WILDMEN in MYANMAR

The RELICT HOMINOID INQUIRY 4:53-66 (2015) Research Article WILDMEN IN MYANMAR: A COMPENDIUM OF PUBLISHED ACCOUNTS AND REVIEW OF THE EVIDENCE Steven G. Platt1, Thomas R. Rainwater2* 1 Wildlife Conservation Society-Myanmar Program, Office Block C-1, Aye Yeik Mon 1st Street, Hlaing Township, Yangon, Myanmar 2 Baruch Institute of Coastal Ecology and Forest Science, Clemson University, P.O. Box 596, Georgetown, SC 29442, USA ABSTRACT. In contrast to other countries in Asia, little is known concerning the possible occurrence of undescribed Hominoidea (i.e., wildmen) in Myanmar (Burma). We here present six accounts from Myanmar describing wildmen or their sign published between 1910 and 1972; three of these reports antedate popularization of wildmen (e.g., yeti and sasquatch) in the global media. Most reports emanate from mountainous regions of northern Myanmar (primarily Kachin State) where wildmen appear to inhabit montane forests. Wildman tracks are described as superficially similar to human (Homo sapiens) footprints, and about the same size to almost twice the size of human tracks. Presumptive pressure ridges were described in one set of wildman tracks. Accounts suggest wildmen are bipedal, 120-245 cm in height, and covered in longish pale to orange-red hair with a head-neck ruff. Wildmen are said to utter distinctive vocalizations, emit strong odors, and sometimes behave aggressively towards humans. Published accounts of wildmen in Myanmar are largely based on narratives provided by indigenous informants. We found nothing to indicate informants were attempting to beguile investigators, and consider it unlikely that wildmen might be confused with other large mammals native to the region. -

The Socioeconomics of State Formation in Medieval Afghanistan

The Socioeconomics of State Formation in Medieval Afghanistan George Fiske Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2012 © 2012 George Fiske All rights reserved ABSTRACT The Socioeconomics of State Formation in Medieval Afghanistan George Fiske This study examines the socioeconomics of state formation in medieval Afghanistan in historical and historiographic terms. It outlines the thousand year history of Ghaznavid historiography by treating primary and secondary sources as a continuum of perspectives, demonstrating the persistent problems of dynastic and political thinking across periods and cultures. It conceptualizes the geography of Ghaznavid origins by framing their rise within specific landscapes and histories of state formation, favoring time over space as much as possible and reintegrating their experience with the general histories of Iran, Central Asia, and India. Once the grand narrative is illustrated, the scope narrows to the dual process of monetization and urbanization in Samanid territory in order to approach Ghaznavid obstacles to state formation. The socioeconomic narrative then shifts to political and military specifics to demythologize the rise of the Ghaznavids in terms of the framing contexts described in the previous chapters. Finally, the study specifies the exact combination of culture and history which the Ghaznavids exemplified to show their particular and universal character and suggest future paths for research. The Socioeconomics of State Formation in Medieval Afghanistan I. General Introduction II. Perspectives on the Ghaznavid Age History of the literature Entrance into western European discourse Reevaluations of the last century Historiographic rethinking Synopsis III. -

Dragons and Serpents in JK Rowling's <I>Harry Potter</I> Series

Volume 27 Number 1 Article 6 10-15-2008 Dragons and Serpents in J.K. Rowling's Harry Potter Series: Are They Evil? Lauren Berman University of Haifa, Israel Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.swosu.edu/mythlore Part of the Children's and Young Adult Literature Commons Recommended Citation Berman, Lauren (2008) "Dragons and Serpents in J.K. Rowling's Harry Potter Series: Are They Evil?," Mythlore: A Journal of J.R.R. Tolkien, C.S. Lewis, Charles Williams, and Mythopoeic Literature: Vol. 27 : No. 1 , Article 6. Available at: https://dc.swosu.edu/mythlore/vol27/iss1/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Mythopoeic Society at SWOSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Mythlore: A Journal of J.R.R. Tolkien, C.S. Lewis, Charles Williams, and Mythopoeic Literature by an authorized editor of SWOSU Digital Commons. An ADA compliant document is available upon request. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To join the Mythopoeic Society go to: http://www.mythsoc.org/join.htm Mythcon 51: A VIRTUAL “HALFLING” MYTHCON July 31 - August 1, 2021 (Saturday and Sunday) http://www.mythsoc.org/mythcon/mythcon-51.htm Mythcon 52: The Mythic, the Fantastic, and the Alien Albuquerque, New Mexico; July 29 - August 1, 2022 http://www.mythsoc.org/mythcon/mythcon-52.htm Abstract Investigates the role and symbolism of dragons and serpents in J.K. Rowling’s Harry Potter series, with side excursions into Lewis and Tolkien for their takes on the topic. Concludes that dragons are morally neutral in her world, while serpents generally represent or are allied with evil. -

Feral Swine Disease Control in China

2014 International Workshop on Feral Swine Disease and Risk Management By Hongxuan He Feral swine diseases prevention and control in China HONGXUAN HE, PH D PROFESSOR OF INSTITUTE OF ZOOLOGY, CHINESE ACADEMY OF SCIENCES EXECUTIVE DEPUTY DIRECTOR OF NATIONAL RESEARCH CENTER FOR WILDLIFE DISEASES COORDINATOR OF ASIA PACIFIC NETWORK OF WILDLIFE BORNE DISEASES CONTENTS · Feral swine in China · Diseases of feral swine · Prevention and control strategies · Influenza in China Feral swine in China 4 Scientific Classification Scientific name: Sus scrofa Linnaeus Common name: Wild boar, wild hog, feral swine, feral pig, feral hog, Old World swine, razorback, Eurasian wild boar, Russian wild boar Feral swine is one of the most widespread group of mammals, which can be found on every continent expect Antarctica. World distribution of feral swine Reconstructed range of feral swine (green) and introduced populations (blue). Not shown are smaller introduced populations in the Caribbean, New Zealand, sub-Saharan Africa and elsewhere. Species of feral swine Now ,there are 4 genera and 16 species recorded in the world today. Western Indian Eastern Indonesian genus genus genus genus Sus scrofa scrofa Sus scrofa Sus scrofa Sus scrofa Sus scrofa davidi sibiricus vittatus meridionalis Sus scrofa Sus scrofa Sus scrofa algira cristatus ussuricus Sus scrofa Attila Sus scrofa Sus scrofa leucomystax nigripes Sus scrofa Sus scrofa riukiuanus libycus Sus scrofa Sus scrofa majori taivanus Sus scrofa moupinensis Feral swine in China Feral swine has a long history in China. About 10,000 years ago, Chinese began to domesticate feral swine. Feral swine in China Domesticated history in China oracle bone inscriptions of “猪” in Different font of “猪” Shang Dynasty Feral swine in China Domesticated history in China The carving of pig in Han Dynasty Feral swine in China Domesticated history in China In ancient time, people domesticated pig in “Zhu juan”. -

Shahnameh) and Balder (Scandinavian Epic)

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by Revista Amazonia Investiga Florencia, Colombia, Vol. 6 Núm. 10 /enero-junio 2017/ 151 Artículo de investigación Interpretation and analysis of epic thinking in Iran and Scandinavia emphasizing the story of Esfandiar (Shahnameh) and Balder (Scandinavian epic) Interpretación y análisis del pensamiento épico en Irán y Escandinavia enfatizando la historia de Esfandiar (Shahnameh) y Balder (épica escandinava) Interpretação e análise do pensamento épico no Irã e na Escandinávia enfatizando a história de Esfandiar (Shahnameh) e Balder (épico escandinavo) Recibido: 9 de abril de 2017. Aceptado: 30 de mayo de 2017 Escrito por: Shahrbanoo Ganjeh39 Alimohammad Moazzeni2* Tofigh Sobhani3 Mohammed Reza Shad Manamen4 Abstract Resumen Apart from the impact and impact of the two Además del impacto y el impacto de las dos lands, a way can be opened in There is a special tierras, se puede abrir una vía en Hay un tema subject that there is a shared point of content in especial en el que hay un punto de contenido it and it is a source of analogy A topic, a tendency compartido y es una fuente de analogía Un tema, and a special content of common interest in two una tendencia y un contenido especial de común different territories. Question one of the most interés en dos territorios diferentes. Pregunta important and frequent points in the history of uno de los puntos más importantes y frecuentes the literatures and beliefs of different lands It is en la historia de las literaturas y creencias de on the side of history and on the side of human diferentes países. -

Siren Motifs on Glazed Dishes

Art This is how the harpies and sirens were seen in Europe in the Middle Ages 34 www.irs-az.com 2(30), SPRING 2017 Aida ISMAYILOVA Siren motifs on glazed dishes (Based on materials of the National Azerbaijan History Museum) www.irs-az.com 35 Art This is how the harpies and sirens were seen in ancient Greece. Image on a ceramic vase he National Azerbaijan History Museum (NAHM) is mation about the semantics of the image with a human rich in archaeological materials belonging to vari- head and a bird’s body. Tous periods of our history, including the 12th-13th First of all, let’s get acquainted with the description centuries. Based on this material evidence, we can study of the material cultural artifacts we mentioned above: the artistic and aesthetic image and world outlook of A fragment of a dish was found in the urban area of the period, as well as its principle of cultural succession. Beylagan in 1963 (1, No 25058). The clay of the glazed From this point of view, we will be talking about archaeo- fragment was bright orange and well fired. The inter- logical materials, which belong to the aforesaid period, nal surface is covered with engobing and is glazed with found in the urban areas of Beylagan and Bandovan and images of birds and plants engraved on it. The outlines handed over to the NAHM from the Nizami museum. of the image are bright brown. The profile of a bird is The particularity of these material cultural artifacts is that depicted from the right side. -

Further Evidence for the Interpretation of the 'Indian Scene' In

Further Evidence for the Interpretation of the ‘Indian Scene’ in the Pre-Islamic Paintings at Afrasiab (Samarkand) Matteo Compareti Venice The Sogdian paintings at Afrasiab opinion, Silvi Antonini’s idea Fragmentary inscriptions on the were discovered accidentally more remains the key for a correct western wall mention the name of than forty years ago during road interpretation of the entire cycle a sovereign, Varkhuman, who construction near Samarkand. of the paintings at Afrasiab. While corresponds to the local king However, only in 1975 was the first a detailed study by Markus Mode recognized as governor of book concerning them published a few years later disputed her Samarkand and Sogdiana by the (Al’baum 1975). Archaeological interpretation (Mode 1993), the Chinese Emperor Gaozong (649- excavations continued at the great specialist of Sogdian studies, 683) in the period between 650- Afrasiab site for some time, the late Boris Marshak, not only 655 (Chavannes 1903, 135).1 In leading to the discovery of other accepted it but also added other 658 Gaozong even sent an envoy fragments of schematic paintings important elements to the general to the court of Varkhuman for an between 1978 and 1985 interpretation of the whole cycle official investiture (Anazawa and (Akhunbabaev 1987). Since 1989 and, especially, of the southern Manome 1976, 21ff., cited by French archaeologists have been wall paintings (Marshak 1994). Kageyama 2002, 320). However, excavating at the ancient site in Soviet scholars continued to study according to Islamic sources, collaboration with Russian and, the Afrasiab paintings, although when Sa‘id ibn Othman conquered after the collapse of the Soviet their interesting results did not Samarkand in 676 he did not find Union, Uzbek colleagues, but become widely known because of any king there.