So Easily Offended

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Suicide and Suicide Prevention a Briefing by the Congress Of

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 259 261 CG 018 362 TITLE Suicide and Suicide Prevention A Briefing by the Subcommittee on Human Services of the Select Committee on Aging. House of Representatives, Ninety-Eighth Congress, Second Session (November 1, 1984, San Francisco, CA). INSTITUTION Congress of the U.S., Washington, D.C. House Select Committee c.1 Aging. REPORT NO House-Comm. pub -98 -497 PUB DATE 85 NOTE 62p.; Portions of the document contain small print. PUB TYPE Legal/Legislative/Regulatory Materials (090) EDRS PRICE MF01 Plus Postage. PC Not Available from EDRS. DESCRIPTORS *Adolescents; Adults; Blacks; Crisis Intervention; Hearings; *Prevention; Research Needs; School Role; *Suicide IDENTIFIERS California; Congress 98th ABSTRACT This document presents the transcripts of a Congressional hearing called to bring attention to the growing problem of suicide. The opening statement of Representative Tom Lantos is presented. Prepared statements of 16 witnesses are provided, including psychotherapists from the Houston International Hospital; a mother and a father of teenage suicide victims; representatives from several suicide prevention centers in California; the executive officer, American Associa7.ion of Suicidology; a student at the University of California; a representative of the California State Department of Education; a representative of a member of Congress from California; the director of the Cindy Smallwood Foundation, Program on Quasi-Morticide, California; the director of pupil personnel and guidance, Oakland California Public Schools; the head of the Suicide Research Unit, National Institute of Mental Health; and a diplomate in clinical psychology from the Menninger Foundation. Topics covered include the prevalence of suicide among teens, the need for public awareness, establishment of a national centralized computer bank on suicide, prevention of adolescent and adult suicide, and s'iicide in the black community. -

Weather Has the Bill Has Matter

T H U R S D A Y 161st YEAR • NO. 227 JANUARY 21, 2016 CLEVELAND, TN 16 PAGES • 50¢ A year of project completions ‘State of the City’ eyes present, future By JOYANNA LOVE spur even more economic growth a step closer toward the Spring Banner Senior Staff Writer FIRST OF 2 PARTS along the APD 40 corridor,” Rowland Branch Industrial Park becoming a said. reality. Celebrating the completion of some today. The City Council recently thanked “A conceptual master plan was long-term projects for the city was a He said the successes of the past state Rep. Kevin Brooks for his work revealed last summer, prepared by highlight of Cleveland Mayor Tom year were a result of hard work by city promoting the need for the project on TVA and the Bradley/Cleveland Rowland’s State of the City address. staff and the Cleveland City Council. the state level by asking that the Industrial Development Board,” “Our city achieved several long- The mayor said, “Exit 20 is one of Legislature name the interchange for Rowland said. term goals the past year, making 2015 our most visible missions accom- him. The interchange being constructed an exciting time,” Rowland said. “But plished in 2015. Our thanks go to the “The wider turn spaces will benefit to give access to the new industrial just as exciting, Cleveland is setting Tennessee Department of trucks serving our existing park has been named for Rowland. new goals and continues to move for- Transportation and its contractors for Cleveland/Bradley County Industrial “I was proud and humbled when I ward, looking to the future for growth a dramatic overhaul of this important Park and the future Spring Branch learned this year the new access was and development.” interchange. -

Wednesday Morning, Nov. 23

WEDNESDAY MORNING, NOV. 23 FRO 6:00 6:30 7:00 7:30 8:00 8:30 9:00 9:30 10:00 10:30 11:00 11:30 COM 4:30 KATU News This Morning (N) Good Morning America (N) (cc) AM Northwest (cc) The View Justin Bieber. (N) (cc) Live! With Kelly Jerry Seinfeld; 2/KATU 2 2 (cc) (Cont’d) (TV14) Howie Mandel. (N) (cc) (TVPG) KOIN Local 6 at 6am (N) (cc) The Early Show (N) (cc) Let’s Make a Deal (N) (cc) (TVPG) The Price Is Right (N) (cc) (TVG) The Young and the Restless (N) (cc) 6/KOIN 6 6 (TV14) Newschannel 8 at Sunrise at 6:00 Today Justin Bieber performs; John O’Hurley. (N) (cc) Anderson (cc) (TVG) 8/KGW 8 8 AM (N) (cc) EXHALE: Core Wild Kratts (cc) Curious George Cat in the Hat Curious George ★★ (‘06) Voices of Will Ferrell, Curious George 2: Follow That Monkey ★★ (‘09) Voic- Curious George: A Very Monkey 10/KOPB 10 10 Fusion (TVG) (TVY) (TVY) Knows a Lot Drew Barrymore. ‘G’ (1:27) es of Tim Curry, Jamie Kennedy. ‘G’ (1:21) Christmas (cc) (TVG) Good Day Oregon-6 (N) Good Day Oregon (N) MORE Good Day Oregon The 700 Club (cc) (TVPG) Law & Order: Criminal Intent Prav- 12/KPTV 12 12 da. (cc) (TV14) Paid Paid Paid Paid Turbo Dogs (cc) Pearlie (TVY7) Through the Bible Paid Paid Paid Paid Paid 22/KPXG 5 5 (TVY7) Changing Your John Hagee Rod Parsley (cc) This Is Your Day Kenneth Cope- Winning With Jason Crabb: Trusting God to Get Behind the Joyce Meyer James Robison Marilyn Hickey 24/KNMT 20 20 World (TVG) Today (cc) (TVG) (TVG) (cc) (TVG) land (TVG) Wisdom You Through Scenes (cc) (cc) (TVG) (cc) Eye Opener (N) (cc) My Name Is Earl My Name Is Earl Swift Justice: Swift Justice: Maury (cc) (TV14) The Steve Wilkos Show (N) (cc) 32/KRCW 3 3 (TV14) (TV14) Jackie Glass Jackie Glass (TV14) Andrew Wom- Paid The Jeremy Kyle Show (N) (cc) Family Feud (N) Family Feud (N) America Now (N) Divorce Court (N) Cheaters (N) (cc) Cheaters (cc) America’s Court Judge Alex (N) 49/KPDX 13 13 mack (TVPG) (cc) (TVPG) (cc) (TVPG) (cc) (TVG) (TVPG) (TV14) (TVPG) (cc) (TVPG) Paid Paid CSI: Miami Attorney may be The Sopranos Tony’s feud with The Sopranos Jackie Jr. -

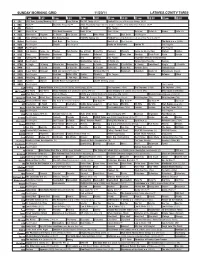

Sunday Morning Grid 10/27/19 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 10/27/19 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Face the Nation (N) News The NFL Today (N) Å Football Cincinnati Bengals vs Los Angeles Rams. (N) Å 4 NBC Today in L.A. Weekend Meet the Press (N) Å NBC4 News Premier League Soccer: Reds vs Spurs 2019 Rugby World Cup 5 CW KTLA 5 Morning News at 7 (N) Å KTLA News at 9 KTLA 5 News at 10am In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News This Week News Hearts of World of X Games (N) Formula 1 Racing 9 KCAL KCAL 9 News Sunday Joel Osteen Jentzen Joel Osteen Jentzen Mike Webb REAL-Diego Paid Program Icons The World’s 1 1 FOX Fox News Sunday FOX NFL Kickoff (N) FOX NFL Sunday (N) Football Los Angeles Chargers at Chicago Bears. (N) Å 1 3 MyNet Paid Program Fred Jordan Freethought Paid Program News The Issue 1 8 KSCI Paid Program Paid Program 2 2 KWHY Paid Program Paid Program 2 4 KVCR Paint Painting Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Painting Cook Mexican Martha Cooking Simply Ming Food 50 2 8 KCET Kid Stew Curious Mixed Nutz Mixed Nutz Darwin’s Biz Kid$ KCET Special Å KCET Special Å KCET Special Å 3 0 ION Jeremiah Youseff In Touch Paid NCIS: Los Angeles Å NCIS: Los Angeles Å NCIS: Los Angeles Å NCIS: Los Angeles Å 3 4 KMEX Conexión Paid Program Como dice el dicho Fútbol Fútbol Mexicano Primera División (N) 4 0 KTBN Pathway Win Walk Prince Carpenter Jackson In Touch PowerPoint It is Written Ed Young Bethel Kelinda Hagee 4 6 KFTR Paid Program Super Ge Super Ge Mundo tuyo Mundo tuyo Masha’s Spooky Stories Paid Program 5 0 KOCE Cat in the Hat Wild Kratts: Creepy Haunted Tree Antiques Roadshow Antiques Roadshow Nature (N) Å 5 2 KVEA Fútbol Premier League (6:55) (N) Fútbol Premier League (N) La Liga Premier Copa 5 6 KDOC Perry Stone In Search Lift Up Paid Cath. -

Uot History Freidland.Pdf

Notes for The University of Toronto A History Martin L. Friedland UNIVERSITY OF TORONTO PRESS Toronto Buffalo London © University of Toronto Press Incorporated 2002 Toronto Buffalo London Printed in Canada ISBN 0-8020-8526-1 National Library of Canada Cataloguing in Publication Data Friedland, M.L. (Martin Lawrence), 1932– Notes for The University of Toronto : a history ISBN 0-8020-8526-1 1. University of Toronto – History – Bibliography. I. Title. LE3.T52F75 2002 Suppl. 378.7139’541 C2002-900419-5 University of Toronto Press acknowledges the financial assistance to its publishing program of the Canada Council for the Arts and the Ontario Arts Council. This book has been published with the help of a grant from the Humanities and Social Sciences Federation of Canada, using funds provided by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada. University of Toronto Press acknowledges the finacial support for its publishing activities of the Government of Canada, through the Book Publishing Industry Development Program (BPIDP). Contents CHAPTER 1 – 1826 – A CHARTER FOR KING’S COLLEGE ..... ............................................. 7 CHAPTER 2 – 1842 – LAYING THE CORNERSTONE ..... ..................................................... 13 CHAPTER 3 – 1849 – THE CREATION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF TORONTO AND TRINITY COLLEGE ............................................................................................... 19 CHAPTER 4 – 1850 – STARTING OVER ..... .......................................................................... -

Tv Pg 5 12-14.Indd

The Goodland Star-News / Friday, December 14, 2007 5 Like puzzles? Then you’ll love sudoku. This mind-bending puzzle FUN BY THE NUM B ERS will have you hooked from the moment you square off, so sharpen your pencil and put your sudoku savvy to the test! Here’s How It Works: Sudoku puzzles are formatted as a 9x9 grid, broken down into nine 3x3 boxes. To solve a sudoku, the numbers 1 through 9 must fill each row, column and box. Each number can appear only once in each row, column and box. You can figure out the order in which the numbers will appear by using the numeric clues already provided in the boxes. The more numbers you name, the easier it gets to solve the puzzle! ANSWER TO TUESD A Y ’S SATURDAY EVENING DECEMBER 15, 2007 SUNDAY EVENING DECEMBER 16, 2007 6PM 6:30 7PM 7:30 8PM 8:30 9PM 9:30 10PM 10:30 6PM 6:30 7PM 7:30 8PM 8:30 9PM 9:30 10PM 10:30 ES E = Eagle Cable S = S&T Telephone ES E = Eagle Cable S = S&T Telephone The First 48: The Run The First 48 (TVPG) (R) The First 48: Torched Paranormal Paranormal The First 48: The Run Flip This House: Elm Street Flip This House: Intern Flip This House: Pipe Flip This House: The Col- Flip This House: Elm Street 36 47 A&E 36 47 A&E Nightmare (R) Affairs (TV G) (R) Dreams (TV G) (R) lege Special (R) Nightmare (R) Around; Night Cap (R) (TVPG) (R) (R) (HD) (R) (HD) Around; Night Cap (R) a Extreme Makeover: Chapin Desperate Housewives Brothers and Sisters: Home KAKE News Overtime Lawyer on Paid Pro- “Surviving Christmas” (‘04, Comedy) Million- Women’s Murder Club KAKE News American Idol Rewind: Entertain- 46 ABC 46 ABC aire rents family for Christmas. -

Memorandum to Clients

Memorandum to Clients June,February, 2007 2008 News and Analysis of Recent Events in the Field of Communications No. 07-0608-02 Soon to be a quarterly chore Meet Form 355 By: Ron Whitworth 703-812-0478 [email protected] s previously reported in the November, 2007, and Janu- For those of you who have not yet taken a close look at the A ary, 2008, Memos to Clients, the Commission has new Form 355 on which program reports will be submitted, adopted a new and extensive program reporting requirement the following is a walk-through introduction to that regula- for TV licensees. The full text of that deci- tory onus (you can find the current draft of sion was released late in January, and the the form at Appendix B to the FCC’s Re- new rules will be implemented 60 days after The bottom line for port and Order at http://hraunfoss.fcc.gov/ notice of approval by the Office of Manage- television stations is clear: edocs_public/attachmatch/FCC-07- ment and Budget (OMB) is published in the the program reporting 205A1.pdf): Federal Register. requirement is on its way. Question 1 – Identification – This section While we can’t be sure of when Federal Preparation for merely seeks standard identifying informa- Regiser publication will occur (much less compliance should begin tion (name and address of licensee, call OMB approval), the bottom line for televi- immediately. sign and FCC ID Number of station, etc.). sion stations is clear: the program reporting No real problem here. requirement is on its way and, barring some last minute miracle, will likely be in place in time to require Question 2 – Programming Information – Here’s where the submission of reports this Summer relating back to pro- things get complicated fast. -

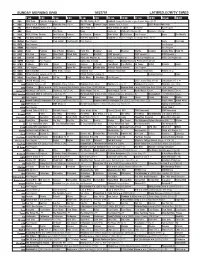

Sunday Morning Grid 11/20/11 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 11/20/11 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Morning (N) Å Face/Nation The NFL Today (N) Å Football Raiders at Minnesota Vikings. (N) Å 4 NBC News Å Meet the Press (N) Å 2011 Presidents Cup Final Day. Singles matches. From Melbourne, Australia. (N) Å 5 CW News Å In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Å This Week-Amanpour News (N) Å News (N) Å News Å Vista L.A. Heroes Vista L.A. 9 KCAL Tomorrow’s Kingdom K. Shook Joel Osteen Prince Mike Webb Paid Best Deals Paid Program 11 FOX Hour of Power (N) (TVG) Fox News Sunday FOX NFL Sunday (N) Football Tampa Bay Buccaneers at Green Bay Packers. (N) Å 13 MyNet Paid Program Best Buys Paid Program Best of L.A. Paid Program The Hoax ››› (2006) 18 KSCI Paid Program Church Paid Program Hecho en Guatemala Iranian TV Paid Program 22 KWHY Paid Program Paid Program 24 KVCR Sid Science Curios -ity Thomas Bob Builder Joy of Paint Paint This Dewberry Wyland’s Home for Christy Rost Kitchen Kitchen 28 KCET Cons. Wubbulous Busytown Peep Pancakes Pufnstuf Lidsville Place, Own Roadtrip Chefs Field Pépin Venetia 30 ION Turning Pnt. Discovery In Touch Paid Beyond Paid Program Inspiration Ministry Campmeeting 34 KMEX Paid Program Muchachitas Como Tu Al Punto (N) Aurora Valle Presenta... Vecinos 40 KTBN K. Hagin Ed Young Miracle-You Redemption Love In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written B. -

Sydney Program Guide

Firefox http://prtten04.networkten.com.au:7778/pls/DWHPROD/Program_Repor... SYDNEY PROGRAM GUIDE Sunday 30th May 2021 06:00 am Sabrina The Teenage Witch (Rpt) CC PG Troll Bride When Sabrina can't find her homework, she follows Salem's advice to consult a professional magic finder. Starring: Melissa Joan Hart, Nick Bakay, Nate Richert, Caroline Rhea, Beth Broderick, Michelle Beaudoin 06:30 am Sabrina The Teenage Witch (Rpt) CC PG Sabrina Gets Her Licence Part 1 All of Sabrina's responsibilities as student, girlfriend and witch pile up on her as she fails her witch's exam and ends up at witch boot camp. Starring: Melissa Joan Hart, Nick Bakay, Nate Richert, Caroline Rhea, Beth Broderick, Michelle Beaudoin 07:00 am The Neighborhood (Rpt) G Welcome To The Climb When Gemma decides to fire a teacher at her school, she's unprepared for the aftermath. Also, Calvin gets a surprise when he faces off with his newspaper carrier. Starring: Cedric Entertainer, The, Max Greenfield 07:30 am The Neighborhood (Rpt) PG Welcome To Logan #2 When Calvin & Dave's basketball teams go head-to-head, Dave surprises the Butlers with tickets & also invites one of his best friends from Michigan who reveals surprising details to Calvin about Dave. Starring: Cedric Entertainer, The, Max Greenfield 08:00 am Neighbours (Rpt) CC PG Yashvi is shocked after hearing the recording of Ned’s conversation with Sheila C. Bea prepares to say goodbye to Ramsay Street. 08:30 am Neighbours (Rpt) CC PG Levi & Harlow both commiserate their breakups with each other over drinks, before having a moment of unexpected connection. -

United States Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit

08-0841-ag (L) ABC, Inc., et al. v. Federal Communications Commission UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE SECOND CIRCUIT SUMMARY ORDER RULINGS BY SUMMARY ORDER DO NOT HAVE PRECEDENTIAL EFFECT. CITATION TO A SUMMARY ORDER FILED ON OR AFTER JANUARY 1, 2007, IS PERMITTED AND IS GOVERNED BY FEDERAL RULE OF APPELLATE PROCEDURE 32.1 AND THIS COURT’S LOCAL RULE 32.1.1. WHEN CITING A SUMMARY ORDER IN A DOCUMENT FILED WITH THIS COURT, A PARTY MUST CITE EITHER THE FEDERAL APPENDIX OR AN ELECTRONIC DATABASE (WITH THE NOTATION “SUMMARY ORDER”). A PARTY CITING A SUMMARY ORDER MUST SERVE A COPY OF IT ON ANY PARTY NOT REPRESENTED BY COUNSEL. At a stated term of the United States Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit, held at the Daniel Patrick Moynihan United States Courthouse, 500 Pearl Street, in the City of New York, on the 4th day of January, two thousand eleven. PRESENT: RICHARD C. WESLEY, DEBRA A. LIVINGSTON, Circuit Judges, JANE A. RESTANI,* Judge. ______________________________ Nos. 08-0841-ag (Lead) 08-1424-ag (Con) 08-1781-ag (Con) 08-1966-ag (Con) ABC, INC., KTRK TELEVISION, INC., WLS TELEVISION, INC., CITADEL COMMUNICATIONS, LLC, WKRN, G.P., YOUNG BROADCASTING OF GREEN BAY, INC., WKOW TELEVISION, INC., WSIL- TV, INC., ABC TELEVISION AFFILIATES ASSOCIATION, CEDAR RAPIDS TELEVISION COMPANY, CENTEX TELEVISION LIMITED PARTNERSHIP, CHANNEL 12 OF BEAUMONT INCORPORATED, DUHAMEL BROADCASTING ENTERPRISES, GRAY TELEVISION LICENSE, INCORPORATED, KATC COMMUNICATIONS, INCORPORATED, KATV LLC, KDNL LICENSEE LLC, KETV HEARST- ARGYLE TELEVISION INCORPORATED, KLTV/KTRE LICENSE SUBSIDIARY LLC, KSTP-TV LLC, KSWO TELEVISION COMPANY INCORPORATED, KTBS INCORPORATED, KTUL LLC, KVUE TELEVISION INCORPORATED, MCGRAW-HILL BROADCASTING COMPANY INCORPORATED, MEDIA GENERAL COMMUNICATIONS HOLDINGS LLC, MISSION BROADCASTING INCORPORATED, MISSISSIPPI BROADCASTING PARTNERS, NEW YORK TIMES MANAGEMENT SERVICES, NEXSTAR * The Honorable Jane A. -

Table of Contents

table of contents hello, i love you: introduction ix can’t fight this feeling: the origins ofglee 1 this is how we do it: the making of glee 14 you’re the one that i want: principal players matthew morrison (will schuester) 22 lea michele (rachel berry) 24 cory monteith (finn hudson) 26 dianna agron (quinn fabray) 28 jane lynch (sue sylvester) 30 jayma mays (emma pillsbury) 32 amber riley (mercedes jones) 33 chris colfer (kurt hummel) 35 jenna ushkowitz (tina cohen-chang) 37 kevin mchale (artie abrams) 38 mark salling (noah “puck” puckerman) 40 jessalyn gilsig (terri schuester) 41 iqbal theba (principal figgins) 43 patrick gallagher (ken tanaka) 45 heather morris (brittany) 46 naya rivera (santana lopez) 48 harry shum jr. (mike chang) 49 dijon talton (matt rutherford) 51 josh sussman (jacob ben israel) 52 season one: may 2009–june 2010 1.01 “pilot” 53 director’s cut differences 57 the evolution of glee: script differences 62 1.02 “showmance” 65 famous people who were in glee clubs 66 q&a: jennifer aspen as kendra giardi 69 1.03 “acafellas” 73 josh groban 74 01_DSBintro_2.indd 5 7/16/10 2:42:44 PM whit hertford as dakota Stanley 75 victor garber as will’s father 76 debra monk as will’s mother 78 john lloyd young as henri st. pierre 79 1.04 “preggers” 82 mike o’malley as burt hummel 83 q&a: stephen tobolowsky as sandy ryerson 85 1.05 “the rhodes not taken” 91 kristin chenoweth as april rhodes 93 gleek speak: amanda kind 96 1.06 “vitamin d” 99 show choirs versus glee clubs 104 1.07 “throwdown” 104 gleek speak: RPing glee 109 1.08 “mash-up” -

Reminder List of Productions Eligible for Awards

REMINDER LIST OF PRODUCTIONS ELIGIBLE FOR AWARDS All films that have qualified for consideration for 2011 Academy Awards in the non-specialized categories are listed alphabetically by title. Voters making selections in their own branch categories list only film titles on their ballots, not the individuals responsible for the various achievements. For that reason, as well as for reasons of printing time and convenience of using this pamphlet, full credit rosters are not provided for the listed films. An exception to the above exists in the four Acting categories, where simply listing titles would not provide enough voting information. Actors Branch members filling out their Nominations ballots must indicate both titles and the particular performers they are voting for. For that reason, the Reminder List provides a listing of up to fifty cast members for each film. Pictures eligible in the Animated Feature Film, Documentary Feature and Foreign Language Film categories are also eligible in the Best Picture category, provided they meet the qualifications for the category. Foreign Language films are eligible for awards in other categories provided they meet the requirements of Awards Rules Two and Three. Notes: A ABDUCTION Taylor Lautner. Lily Collins. Alfred Molina. Jason Isaacs. Maria Bello. Sigourney Weaver. Denzel Whitaker. Michael Nyqvist. Jake Andolina. Oriah Acima Andrews. Ken Arnold. Steve Blass. Derek Burnell. Ben Cain. Holly Scott Cavanaugh. Radick Cembrzynski. Richard Cetrone. Mike Clark. Jack Erdie. Rita Gregory. Tim Griffin. Nathan Hollabaugh. Mike Lee. James Liebro. Frank Lloyd. Christopher Mahoney. Emily Peachey. William Peltz. Elisabeth Rohm. Nickola Shreli. Victor Slezak. Antonique Smith. Roger Guenveur Smith.