FCC V. Fox Television Stations, Inc., 129 S

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Suicide and Suicide Prevention a Briefing by the Congress Of

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 259 261 CG 018 362 TITLE Suicide and Suicide Prevention A Briefing by the Subcommittee on Human Services of the Select Committee on Aging. House of Representatives, Ninety-Eighth Congress, Second Session (November 1, 1984, San Francisco, CA). INSTITUTION Congress of the U.S., Washington, D.C. House Select Committee c.1 Aging. REPORT NO House-Comm. pub -98 -497 PUB DATE 85 NOTE 62p.; Portions of the document contain small print. PUB TYPE Legal/Legislative/Regulatory Materials (090) EDRS PRICE MF01 Plus Postage. PC Not Available from EDRS. DESCRIPTORS *Adolescents; Adults; Blacks; Crisis Intervention; Hearings; *Prevention; Research Needs; School Role; *Suicide IDENTIFIERS California; Congress 98th ABSTRACT This document presents the transcripts of a Congressional hearing called to bring attention to the growing problem of suicide. The opening statement of Representative Tom Lantos is presented. Prepared statements of 16 witnesses are provided, including psychotherapists from the Houston International Hospital; a mother and a father of teenage suicide victims; representatives from several suicide prevention centers in California; the executive officer, American Associa7.ion of Suicidology; a student at the University of California; a representative of the California State Department of Education; a representative of a member of Congress from California; the director of the Cindy Smallwood Foundation, Program on Quasi-Morticide, California; the director of pupil personnel and guidance, Oakland California Public Schools; the head of the Suicide Research Unit, National Institute of Mental Health; and a diplomate in clinical psychology from the Menninger Foundation. Topics covered include the prevalence of suicide among teens, the need for public awareness, establishment of a national centralized computer bank on suicide, prevention of adolescent and adult suicide, and s'iicide in the black community. -

Entertainment & Syndication Fitch Group Hearst Health Hearst Television Magazines Newspapers Ventures Real Estate & O

hearst properties WPBF-TV, West Palm Beach, FL SPAIN Friendswood Journal (TX) WYFF-TV, Greenville/Spartanburg, SC Hardin County News (TX) entertainment Hearst España, S.L. KOCO-TV, Oklahoma City, OK Herald Review (MI) & syndication WVTM-TV, Birmingham, AL Humble Observer (TX) WGAL-TV, Lancaster/Harrisburg, PA SWITZERLAND Jasper Newsboy (TX) CABLE TELEVISION NETWORKS & SERVICES KOAT-TV, Albuquerque, NM Hearst Digital SA Kingwood Observer (TX) WXII-TV, Greensboro/High Point/ La Voz de Houston (TX) A+E Networks Winston-Salem, NC TAIWAN Lake Houston Observer (TX) (including A&E, HISTORY, Lifetime, LMN WCWG-TV, Greensboro/High Point/ Local First (NY) & FYI—50% owned by Hearst) Winston-Salem, NC Hearst Magazines Taiwan Local Values (NY) Canal Cosmopolitan Iberia, S.L. WLKY-TV, Louisville, KY Magnolia Potpourri (TX) Cosmopolitan Television WDSU-TV, New Orleans, LA UNITED KINGDOM Memorial Examiner (TX) Canada Company KCCI-TV, Des Moines, IA Handbag.com Limited Milford-Orange Bulletin (CT) (46% owned by Hearst) KETV, Omaha, NE Muleshoe Journal (TX) ESPN, Inc. Hearst UK Limited WMTW-TV, Portland/Auburn, ME The National Magazine Company Limited New Canaan Advertiser (CT) (20% owned by Hearst) WPXT-TV, Portland/Auburn, ME New Canaan News (CT) VICE Media WJCL-TV, Savannah, GA News Advocate (TX) HEARST MAGAZINES UK (A+E Networks is a 17.8% investor in VICE) WAPT-TV, Jackson, MS Northeast Herald (TX) VICELAND WPTZ-TV, Burlington, VT/Plattsburgh, NY Best Pasadena Citizen (TX) (A+E Networks is a 50.1% investor in VICELAND) WNNE-TV, Burlington, VT/Plattsburgh, -

Brief of Petitioner for FCC V. Fox Television Stations, 07-582

No. 07-582 In the Supreme Court of the United States ________________ FEDERAL COMMUNICATIONS COMMISSION AND UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, Petitioners, v. FOX TELEVISION STATIONS, INC., ET AL., Respondents. _________________ On Writ of Certiorari to the United States Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit _________________ AMICUS CURIAE BRIEF OF NATIONAL RELIGIOUS BROADCASTERS IN SUPPORT OF PETITIONERS ___________________ Craig L. Parshall Joseph C. Chautin III Counsel of Record Elise M. Stubbe General Counsel Mark A. Balkin National Religious Co-Counsel Broadcasters Hardy, Carey, Chautin 9510 Technology Dr. & Balkin, LLP Manassas, VA 20110 1080 West Causeway 703-331-4517 Approach Mandeville, LA 70471 985-629-0777 QUESTION PRESENTED FOR REVIEW Amicus adopts the question presented as presented by Petitioner. The question presented for review is as follows: Whether the court of appeals erred in striking down the Federal Communications Commission’s determination that the broadcast of vulgar expletives may violate federal restrictions on the broadcast of “any obscene, indecent, or profane language,” 18 U.S.C. § 1464, see 47 C.F.R. § 73.3999, when the expletives are not repeated. i TABLE OF CONTENTS QUESTION PRESENTED FOR REVIEW .................i TABLE OF AUTHORITIES .......................................v INTEREST OF AMICUS CURIAE ............................x STATEMENT OF THE CASE .................................xii SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT ..................................xii ARGUMENT ..............................................................1 I. THE FCC’S REASONS FOR ADJUSTING ITS INDECENCY POLICY WERE RATIONAL AND REASONABLE .....................1 A. The Court of Appeals Failed to Give the Required Deference and Latitude to the FCC ..................................................1 B. The FCC Gave Sufficient and Adequate Reasoning Why its Prior Indecency Policy Regarding Fleeting Expletives was Unworkable and Required Adjustment .................................3 1. -

PHANTOM THREAD Sonya Clark ’85 Unravels the Power of the Mundane and the Sacred

SIDWELL Contents FRIENDS MAGAZINE Summer 2021 Volume 92 Number 3 LEADERSHIP Head of School DEPARTMENTS Will your Bryan K. Garman 2 REFLECTIONS FROM THE HEAD OF SCHOOL Chief Communications Officer Annual Fund Hellen Hom-Diamond Remembering Peace Speaker Michiko Yamaoka and the responsibility of survivorship. gift really EDITORIAL 4 ON CAMPUS Editor-in-Chief A spirited return to in-person learning, micromester Sacha Zimmerman make a lets students get their feet wet, the BSU production Art Director goes virtual, fond farewells to long-serving faculty, difference? Meghan Leavitt and more. Contributing Designer 04 24 THE ARCHIVIST Alice Ashe The long history of the paper crane at Sidwell Friends. Senior Writers YES. Natalie Champ 44 ALUMNI ACTION Kristen Page Bob Woodward (P ’94, ’15); Mei Xu (P ’19, ’21); Alumni Editors Adama Konteh Hamadi ’04. Emma O’Leary 51 CLASS NOTES Anna Wyeth Virtual Reunions ping alumni around the globe. Contributing Writers Every gift—your Loren Hardenbergh 83 WORDS WITH FRIENDS Caleb Morris “A Heart to Heart” Contributing Photographers 26 84 LAST LOOK gift—matters. Freed Photography Susie Shaffer “The Message, Not the Medium” As a donor, you make an immediate and Digital Producers Anthony La Fleur meaningful impact on everyday experiences Sarah Randall FEATURES for Sidwell Friends students. 26 INTO THE FOLD CONNECT WITH SIDWELL FRIENDS Paper cranes return to campus in a pan-Asian And when you become an Annual Fund donor, @sidwellfriends celebration of Asian American Pacific Islander Heritage @sidwellfriends Month—and why this year it was more important than you join a community of donors who are committed @sidwellfriends ever. -

Broadcasting Ii Aug 5

The Fifth Estate R A D I O T E L E V I S I O N C A B L E S A T E L L I T E Broadcasting ii Aug 5 WE'RE PROUD TO BE VOTED THE TWIN CITIES' #1 MUSIC STATION FOR 7 YEARS IN A ROW.* And now, VIKINGS Football! Exciting play -by-play with Joe McConnell and Stu Voigt, plus Bud Grant 4 times a week. Buy a network of 55 stations. Contact Tim Monahan at 612/642 -4141 or Christal Radio for details AIWAYS 95 AND SUNNY.° 'Art:ron 1Y+ Metro Shares 6A/12M, Mon /Sun, 1979-1985 K57P-FM, A SUBSIDIARY OF HUBBARD BROADCASTING. INC. I984 SUhT OGlf ZZ T s S-lnd st-'/AON )IMM 49£21 Z IT 9.c_. I Have a Dream ... Dr. Martin Luther KingJr On January 15, 1986 Dr. King's birthday becomes a National Holiday KING... MONTGOMERY For more information contact: LEGACY OF A DREAM a Fox /Lorber Representative hour) MEMPHIS (Two Hours) (One-half TO Written produced and directed Produced by Ely Landau and Kaplan. First Richard Kaplan. Nominated for MFOXILORBER by Richrd at the Americ Film Festival. Narrated Academy Award. Introduced by by Jones. Harry Belafonte. JamcsEarl "Perhaps the most important film FOX /LORBER Associates, Inc. "This is a powerful film, a stirring documentary ever made" 432 Park Avenue South film. se who view it cannot Philadelphia Bulletin New York, N.Y. 10016 fail to be moved." Film News Telephone: (212) 686 -6777 Presented by The Dr.Martin Luther KingJr.Foundation in association with Richard Kaplan Productions. -

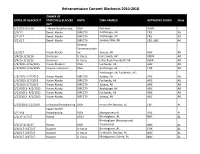

Retrans Blackouts 2010-2018

Retransmission Consent Blackouts 2010-2018 OWNER OF DATES OF BLACKOUT STATION(S) BLACKED MVPD DMA NAME(S) NETWORKS DOWN State OUT 6/12/16-9/5/16 Tribune Broadcasting DISH National WGN - 2/3/17 Denali Media DIRECTV AncHorage, AK CBS AK 9/21/17 Denali Media DIRECTV AncHorage, AK CBS AK 9/21/17 Denali Media DIRECTV Juneau-Stika, AK CBS, NBC AK General CoMMunication 12/5/17 Vision Alaska Inc. Juneau, AK ABC AK 3/4/16-3/10/16 Univision U-Verse Fort SMitH, AK KXUN AK 3/4/16-3/10/16 Univision U-Verse Little Rock-Pine Bluff, AK KLRA AK 1/2/2015-1/16/2015 Vision Alaska II DISH Fairbanks, AK ABC AK 1/2/2015-1/16/2015 Coastal Television DISH AncHorage, AK FOX AK AncHorage, AK; Fairbanks, AK; 1/5/2013-1/7/2013 Vision Alaska DIRECTV Juneau, AK ABC AK 1/5/2013-1/7/2013 Vision Alaska DIRECTV Fairbanks, AK ABC AK 1/5/2013-1/7/2013 Vision Alaska DIRECTV Juneau, AK ABC AK 3/13/2013- 4/2/2013 Vision Alaska DIRECTV AncHorage, AK ABC AK 3/13/2013- 4/2/2013 Vision Alaska DIRECTV Fairbanks, AK ABC AK 3/13/2013- 4/2/2013 Vision Alaska DIRECTV Juneau, AK ABC AK 1/23/2018-2/2/2018 Lockwood Broadcasting DISH Huntsville-Decatur, AL CW AL SagaMoreHill 5/22/18 Broadcasting DISH MontgoMery AL ABC AL 1/1/17-1/7/17 Hearst AT&T BirMingHaM, AL NBC AL BirMingHaM (Anniston and 3/3/17-4/26/17 Hearst DISH Tuscaloosa) NBC AL 3/16/17-3/27/17 RaycoM U-Verse BirMingHaM, AL FOX AL 3/16/17-3/27/17 RaycoM U-Verse Huntsville-Decatur, AL NBC AL 3/16/17-3/27/17 RaycoM U-Verse MontgoMery-SelMa, AL NBC AL Retransmission Consent Blackouts 2010-2018 6/12/16-9/5/16 Tribune Broadcasting DISH -

10 27 2003 SBGI Names Porter GM in Madison

Sinclair Broadcast Group http://www.sbgi.net/press/2003/release_20031027_56.shtml SBG Names Porter GM in Madison BALTIMORE (October 27, 2003) - Sinclair Broadcast Group, Inc. (Nasdaq: SBGI) announced today that Marshall Porter has been named General Manager for WMSN-TV (FOX 47) in Madison, Wisconsin. The announcement was made by Steve Marks, Chief Operating Officer of Sinclair's television group. In making the announcement, Mr. Marks said, "We are excited to have Marshall join us in Madison. He brings a great deal of sales and station management experience and will be a tremendous asset as we continue to grow WMSN." Commenting on his appointment, Mr. Porter stated, "I am very excited about the opportunity to lead the WMSN-TV team and equally excited to return to Wisconsin. The station has a solid foundation built around its people and program line-up, and I look forward to continuing to build upon the station's successful mix of community involvement and quality program offerings." Mr. Porter's television career spans 24 years, most recently serving as Senior Vice President / General Manager and Corporate Director of Sales for Citadel Communications and WOI-TV in Des Moines, Iowa since 2000. Prior to that, he was General Manager at WHBF-TV in Rock Island, Illinois from 1996 to 2000. Mr. Porter's 12 years of sales management experience include stops at WQAD-TV, Moline, IL, WAOW-TV, Wausau, WI and KDUB-TV, Dubuque, IA. Mr. Porter received his Bachelor of Science degree in Communications from Emerson College in Boston. Sinclair Broadcast Group, Inc., one of the largest and most diversified television broadcasting companies, owns and operates, programs or provides sales services to 62 television stations in 39 markets. -

GRAY TELEVISION, INC. (Exact Name of Registrant As Specified in Its Charter)

UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION Washington, D.C. 20549 FORM 8-K CURRENT REPORT Pursuant to Section 13 or 15(d) of the Securities and Exchange Act of 1934 Date of Report (Date of earliest event reported): October 16, 2013 (October 15, 2013) GRAY TELEVISION, INC. (Exact name of registrant as specified in its charter) Georgia 1-13796 58-0285030 (State of incorporation (Commission (IRS Employer or organization) File Number) Identification No.) 4370 Peachtree Road, NE, Atlanta, GA 30319 (Address of Principal Executive Offices) (Zip Code) Registrant’s telephone number, including area code: (404) 504-9828 Not Applicable (Former name or former address, if changed since last report) Check the appropriate box below if the Form 8-K filing is intended to simultaneously satisfy the filing obligation of the registrant under any of the following provisions: ¨ Written communications pursuant to Rule 425 under the Securities Act (17 CFR 230.425) ¨ Soliciting material pursuant to Rule 14a-12 under the Exchange Act (17 CFR 240.14a-12) ¨ Pre-commencement communications pursuant to Rule 14d-2(b) under the Exchange Act (17 CFR 240.14d-2(b)) ¨ Pre-commencement communications pursuant to Rule 13e-4(c) under the Exchange Act (17 CFR 240.13e-4(c)) Item 7.01. Regulation FD Disclosure. In connection with various meetings that management of Gray Television, Inc. (the “Company”) expects to hold with investors, the Company has prepared a slide presentation. A copy of the slides to be used in connection with such investor meetings is furnished as Exhibit 99.1 hereto and incorporated herein by this reference. -

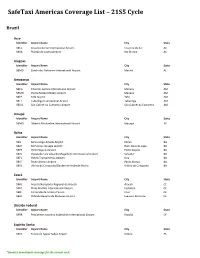

Safetaxi Americas Coverage List – 21S5 Cycle

SafeTaxi Americas Coverage List – 21S5 Cycle Brazil Acre Identifier Airport Name City State SBCZ Cruzeiro do Sul International Airport Cruzeiro do Sul AC SBRB Plácido de Castro Airport Rio Branco AC Alagoas Identifier Airport Name City State SBMO Zumbi dos Palmares International Airport Maceió AL Amazonas Identifier Airport Name City State SBEG Eduardo Gomes International Airport Manaus AM SBMN Ponta Pelada Military Airport Manaus AM SBTF Tefé Airport Tefé AM SBTT Tabatinga International Airport Tabatinga AM SBUA São Gabriel da Cachoeira Airport São Gabriel da Cachoeira AM Amapá Identifier Airport Name City State SBMQ Alberto Alcolumbre International Airport Macapá AP Bahia Identifier Airport Name City State SBIL Bahia-Jorge Amado Airport Ilhéus BA SBLP Bom Jesus da Lapa Airport Bom Jesus da Lapa BA SBPS Porto Seguro Airport Porto Seguro BA SBSV Deputado Luís Eduardo Magalhães International Airport Salvador BA SBTC Hotéis Transamérica Airport Una BA SBUF Paulo Afonso Airport Paulo Afonso BA SBVC Vitória da Conquista/Glauber de Andrade Rocha Vitória da Conquista BA Ceará Identifier Airport Name City State SBAC Aracati/Aeroporto Regional de Aracati Aracati CE SBFZ Pinto Martins International Airport Fortaleza CE SBJE Comandante Ariston Pessoa Cruz CE SBJU Orlando Bezerra de Menezes Airport Juazeiro do Norte CE Distrito Federal Identifier Airport Name City State SBBR Presidente Juscelino Kubitschek International Airport Brasília DF Espírito Santo Identifier Airport Name City State SBVT Eurico de Aguiar Salles Airport Vitória ES *Denotes -

Brief for Respondents

No. 10-1293 In the Morris Tyler Moot Court of Appeals at Yale FEDERAL COMMUNICATIONS COMMISSION, ET AL., PETITIONERS v. FOX TELEVISION STATIONS, INC., ET AL., RESPONDENTS FEDERAL COMMUNICATIONS COMMISSION AND UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, PETITIONERS v. ABC, INC., ET AL., RESPONDENTS ON WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE SECOND CIRCUIT BRIEF FOR THE RESPONDENTS LEWIS BOLLARD JONATHAN SIEGEL Counsel for Respondents The Yale Law School 127 Wall Street New Haven, CT 06511 (203) 432–4992 QUESTIONS PRESENTED The FCC forbids the broadcasting of indecent speech, defined “as material that, in context, depicts or describes sexual or excretory activities or organs in terms patently offensive as measured by contemporary community standards for the broadcast medium.” J.A. 49. The questions presented are: 1. Whether the FCC’s definition of indecency violates the Fifth Amendment because it is impermissibly vague. 2. Whether the FCC’s ban on indecency violates the First Amendment because it is not narrowly tailored and because it does not require scienter for liability. i PARTIES TO THE PROCEEDINGS Petitioners are the Federal Communications Commission and the United States of America. Respondents who were petitioners in the court of appeals in Fox Television Stations, Inc. v. FCC are: Fox Television Stations, Inc., CBS Broadcasting Inc., WLS Television, Inc., KTRK Television, Inc., KMBC Hearst-Argyle Television, Inc., and ABC Inc. Respondents who were intervenors in the court of appeals in Fox Television Stations, Inc. v. FCC are: NBC Universal, Inc., NBC Telemundo License Co., NBC Television Affiliates, FBC Television Affiliates Association, CBS Television Network Affiliates, Center for the Creative Community, Inc., doing business as Center for Creative Voices in Media, Inc., and ABC Television Affiliates Association. -

Federal Register/Vol. 85, No. 103/Thursday, May 28, 2020

32256 Federal Register / Vol. 85, No. 103 / Thursday, May 28, 2020 / Proposed Rules FEDERAL COMMUNICATIONS closes-headquarters-open-window-and- presentation of data or arguments COMMISSION changes-hand-delivery-policy. already reflected in the presenter’s 7. During the time the Commission’s written comments, memoranda, or other 47 CFR Part 1 building is closed to the general public filings in the proceeding, the presenter [MD Docket Nos. 19–105; MD Docket Nos. and until further notice, if more than may provide citations to such data or 20–105; FCC 20–64; FRS 16780] one docket or rulemaking number arguments in his or her prior comments, appears in the caption of a proceeding, memoranda, or other filings (specifying Assessment and Collection of paper filers need not submit two the relevant page and/or paragraph Regulatory Fees for Fiscal Year 2020. additional copies for each additional numbers where such data or arguments docket or rulemaking number; an can be found) in lieu of summarizing AGENCY: Federal Communications original and one copy are sufficient. them in the memorandum. Documents Commission. For detailed instructions for shown or given to Commission staff ACTION: Notice of proposed rulemaking. submitting comments and additional during ex parte meetings are deemed to be written ex parte presentations and SUMMARY: In this document, the Federal information on the rulemaking process, must be filed consistent with section Communications Commission see the SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION 1.1206(b) of the Commission’s rules. In (Commission) seeks comment on several section of this document. proceedings governed by section 1.49(f) proposals that will impact FY 2020 FOR FURTHER INFORMATION CONTACT: of the Commission’s rules or for which regulatory fees. -

Weather Has the Bill Has Matter

T H U R S D A Y 161st YEAR • NO. 227 JANUARY 21, 2016 CLEVELAND, TN 16 PAGES • 50¢ A year of project completions ‘State of the City’ eyes present, future By JOYANNA LOVE spur even more economic growth a step closer toward the Spring Banner Senior Staff Writer FIRST OF 2 PARTS along the APD 40 corridor,” Rowland Branch Industrial Park becoming a said. reality. Celebrating the completion of some today. The City Council recently thanked “A conceptual master plan was long-term projects for the city was a He said the successes of the past state Rep. Kevin Brooks for his work revealed last summer, prepared by highlight of Cleveland Mayor Tom year were a result of hard work by city promoting the need for the project on TVA and the Bradley/Cleveland Rowland’s State of the City address. staff and the Cleveland City Council. the state level by asking that the Industrial Development Board,” “Our city achieved several long- The mayor said, “Exit 20 is one of Legislature name the interchange for Rowland said. term goals the past year, making 2015 our most visible missions accom- him. The interchange being constructed an exciting time,” Rowland said. “But plished in 2015. Our thanks go to the “The wider turn spaces will benefit to give access to the new industrial just as exciting, Cleveland is setting Tennessee Department of trucks serving our existing park has been named for Rowland. new goals and continues to move for- Transportation and its contractors for Cleveland/Bradley County Industrial “I was proud and humbled when I ward, looking to the future for growth a dramatic overhaul of this important Park and the future Spring Branch learned this year the new access was and development.” interchange.