Gore Vidal (1925-2012)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Weather Underground Rises from the Ashes: They're Baack!

Weather Underground Rises from the Ashes: They're Baack! I attended part of a January 20, 2006, "day workshop of interventions" — aka "a day of dialogic interventions" — at Columbia University on "Radical Politics and the Ethics of Life."[1] The event aimed "to stage a series of encounters . to bring to light . the political aporias [sic] erected by the praxis of urban guerrilla groups" in Europe and the United States from the 1960s to the 80s.[2] Hosted by Columbia's Anthropology Department, workshop speakers included veterans and leaders of the Weather Underground Bernardine Dohrn and Bill Ayers, historian Jeremy Varon, poststructuralist theorist Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak and a dozen others. The panel I sat through was just awful.[3] Veterans of Weather (as well as some fans) seem to be on a drive to rehabilitate, cleanse, and perhaps revive it — not necessarily as a new organization, but rather as an ideological component of present and future movements. There have been signs of such a sanitization and romanticization for some time. A landmark in this rehabilitation is Bill Ayers, Fugitive Days: A Memoir (Beacon Press 2001; Penguin Books 2003). This is a dubious account, full of anachronisms, inaccuracies, unacknowledged borrowings from unnamed sources (such as the documentary, Atomic Cafe, 17-19), adding up to an attempt to cover over the fact that Ayers was there only for a part of the things he describes in a volume that nonetheless presents itself as a memoir. It's also faux literary and soft core ("warm and wet and welcoming"(68)), "ruby mouth"(38), "she felt warm and moist"(81)), full of archaic sexism, littered with boasts of Ayers's sexual achievements, utterly untouched by feminism. -

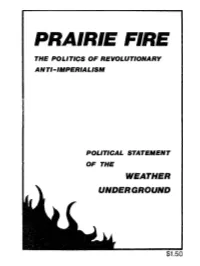

The Politics of Revolutionary Anti-Imperialism

FIRE THE POLITICS OF REVOLUTIONARY ANTI-IMPERIALISM ---- - ... POLITICAL STATEMENT OF THE UND£ $1.50 Prairie Fire Distributing Lo,rnrrntte:e This edition ofPrairie Fire is published and copyrighted by Communications Co. in response to a written request from the authors of the contents. 'rVe have attempted to produce a readable pocket size book at a re'ls(m,tbl.e cost. Weare printing as many as fast as limited resources allow. We hope that people interested in Revolutionary ideas and events will morc and better editions possible in the future. (And that this edition at least some extent the request made by its authors.) PO Box 411 Communications Co. Times Plaza Sta. PO Box 40614, Sta. C Brooklyn, New York San FrancisQ:O, Ca. 11217 94110 Quantity rates upon request to Peoples' Bookstores and Community organiza- tlOBS. PRAIRIE FIRE THE POLITICS OF REVOLUTIONARY ANTI-IMPERIALISM POLITICAL STATEMENT , OF THE WEATHER Copyright © 1974 by Communications Co. UNDERGROUND All rights reserved The pUblisher's copyright is not intended to discourage the use ofmaterial from this book for political debate and study. It is intended to prevent false and distorted reproduction and profiteering. Aside from those limits, people are free to utilize the material. This edition is a copy of the original which was Printed Underground In the US For The People Published by Communications Co. 1974 +h(~ of OlJr(1)mYl\Q~S tJ,o ~Q.Ve., ~·Ir tllJ€~ it) #i s\-~~\~ 'Yt)l1(ch ~, \~ 10 ~~\ d~~~ee.' l1~rJ 1I'bw~· reU'w) ~it· e\rrp- f'0nit'l)o yralt· ~YZlpmu>I')' ca~-\e.v"C2lmp· ~~ ~[\.ll10' ~li~ ~n. -

Bernardine Dohrn

Bernardine Dorhn: Never the Good Girl, Not Then, not Now: An Interview By Jonah Raskin Who doesn’t have a reaction to the name and the reputation of Bernadine Dohrn? Is there anyone over the age of 60 who doesn’t remember her role at the outrageous Days of Rage demonstrations, her picture on FBI “wanted posters,” or her dramatic surrender to law enforcement officials in Chicago after a decade as a fugitive? To former members of SDS, anti-war activists, Yippies, Black Panthers, White Panthers, women’s liberationists, along with students and scholars of Weatherman and the Weather Underground, she probably needs no introduction. Sam Green featured her in his award-winning 2002 film, The Weather Underground. Todd Gitlin added to her iconic stature in his benchmark cultural history, The Sixties, though he was never on her side of the ideological splits or she on his. Dozens of books about the long decade of defiance have documented and mythologized Dohrn’s role as an American radical. Of course, her flamboyant husband and long-time partner, Bill Ayers, has been at her side for decades, aiding and abetting her much of the time, and adding to her legendary renown and notoriety. Born in 1942, and a diligent student at the University of Chicago, she attended law school there and in the late 1960s “stepped out of the role of the good girl," as she once put it. She has never really stepped back into it again, though she’s been a wife, a mother, and a professional woman for more years than she was a street fighting woman. -

Monthly Review Press Catalog, 2011

PAID PAID Social Structure RIPON, WI and Forms of NON-PROFIT U.S. POSTAGE U.S. POSTAGE Consciousness ORGANIZATION ORGANIZATION PERMIT NO. 100 volume ii The Dialectic of Structure and History István Mészáros Class Dismissed WHY WE CANNOT TEACH OR LEARN OUR WAY OUT OF INEQUALITY John Marsh JOSÉ CARLOS MARIÁTEGUI an anthology MONTHLY REVIEW PRESS Harry E. Vanden and Marc Becker editors and translators the story of the center for constitutional rights How Venezuela and Cuba are Changing the World’s Conception of Health Care the people’s RevolutionaRy lawyer DOCTORS 2011 Albert Ruben Steve Brouwer WHAT EVERY ENVIRONMENTALIST NEEDS TO KNOW ABOUT CAPITALISM JOHN BELLAMY FOSTER FRED MAGDOFF monthly review press review monthly #6W 29th Street, 146 West NY 10001 New York, www.monthlyreview.org 2011 MRP catalog:TMOI.qxd 1/4/2011 3:49 PM Page 1 THE DEVIL’S MILK A Social History of Rubber JOHN TULLY From the early stages of primitivehistory accu- mulation“ to the heights of the industrial revolution and beyond, rubber is one of a handful of commodities that has played a crucial role in shaping the modern world, and yet, as John Tully shows in this remarkable book, laboring people around the globe have every reason to THE DEVIL’S MILK regard it as “the devil’s milk.” All the A S O C I A L H I S T O R Y O F R U B B E R advancements made possible by rubber have occurred against a backdrop of seemingly endless exploitation, con- quest, slavery, and war. -

Obscene Odes on the Windows of the Skull": Deconstructing the Memory of the Howl Trial of 1957

W&M ScholarWorks Undergraduate Honors Theses Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 12-2013 "Obscene Odes on the Windows of the Skull": Deconstructing the Memory of the Howl Trial of 1957 Kayla D. Meyers College of William and Mary Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/honorstheses Part of the American Studies Commons Recommended Citation Meyers, Kayla D., ""Obscene Odes on the Windows of the Skull": Deconstructing the Memory of the Howl Trial of 1957" (2013). Undergraduate Honors Theses. Paper 767. https://scholarworks.wm.edu/honorstheses/767 This Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Undergraduate Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. “Obscene Odes on the Windows of the Skull”: Deconstructing The Memory of the Howl Trial of 1957 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Bachelor of Arts in American Studies from The College of William and Mary by Kayla Danielle Meyers Accepted for ___________________________________ (Honors, High Honors, Highest Honors) ________________________________________ Charles McGovern, Director ________________________________________ Arthur Knight ________________________________________ Marc Raphael Williamsburg, VA December 3, 2013 Table of Contents Introduction: The Poet is Holy.........................................................................................................2 -

GORE VIDAL the United States of Amnesia

Amnesia Productions Presents GORE VIDAL The United States of Amnesia Film info: http://www.tribecafilm.com/filmguide/513a8382c07f5d4713000294-gore-vidal-the-united-sta U.S., 2013 89 minutes / Color / HD World Premiere - 2013 Tribeca Film Festival, Spotlight Section Screening: Thursday 4/18/2013 8:30pm - 1st Screening, AMC Loews Village 7 - 3 Friday 4/19/2013 12:15pm – P&I Screening, Chelsea Clearview Cinemas 6 Saturday 4/20/2013 2:30pm - 2nd Screening, AMC Loews Village 7 - 3 Friday 4/26/2013 5:30pm - 3rd Screening, Chelsea Clearview Cinemas 4 Publicity Contact Sales Contact Matt Johnstone Publicity Preferred Content Matt Johnstone Kevin Iwashina 323 938-7880 c. office +1 323 7829193 [email protected] mobile +1 310 993 7465 [email protected] LOG LINE Anchored by intimate, one-on-one interviews with the man himself, GORE VIDAL: THE UNITED STATS OF AMNESIA is a fascinating and wholly entertaining tribute to the iconic Gore Vidal. Commentary by those who knew him best—including filmmaker/nephew Burr Steers and the late Christopher Hitchens—blends with footage from Vidal’s legendary on-air career to remind us why he will forever stand as one of the most brilliant and fearless critics of our time. SYNOPSIS No twentieth-century figure has had a more profound effect on the worlds of literature, film, politics, historical debate, and the culture wars than Gore Vidal. Anchored by intimate one-on-one interviews with the man himself, Nicholas Wrathall’s new documentary is a fascinating and wholly entertaining portrait of the last lion of the age of American liberalism. -

Lincoln: a Novel (Narratives of Empire, Book 2)

ACCLAIM FOR GORE VIDAL’s LINCOLN “A brilliant marriage of fact and imagination. It’s just about everything a novel should be— pleasure, information, moral insight. [Vidal] gives us a man and a time so alive and real that we see and feel them.… A superb book.” —The Plain Dealer “Utterly convincing … Vidal is concerned with dissecting, obsessively and often brilliantly, the roots of personal ambition as they give rise to history itself.” —Joyce Carol Oates, The New York Times Book Review “An astonishing achievement.… Vidal is a masterly American historical novelist.… Vidal’s imagination of American politics, then and now, is so powerful as to compel awe.” —Harold Bloom, The New York Review of Books “The best American historical novel I’ve read in recent years.” —Arthur Schlesinger, Jr., Vanity Fair “[A] literary triumph. There is no handy and cheap psychoanalysis here, but rather a careful scrutiny of the actions that spring from the core of Lincoln himself.… We are left to gure out the man as if he were a real person in our lives.” —Chicago Sun-Times “Lincoln reaches for sublimity.… This novel will, I suspect, maintain a permanent place in American letters.” —Andrew Delbanco, The New Republic “Vidal is the best all-round American man of letters since Edmund Wilson.… This is his most moving book.” —Newsweek “It is remarkable how much good history Mr. Vidal has been able to work into his novel. And I nd—astonishingly enough, since I have been over this material so many times—that Mr. Vidal has made of this familiar record a narrative that sustained my interest right up to the final page.” —Professor David Donald, Harvard University GORE VIDAL LINCOLN Gore Vidal was born in 1925 at the United States Military Academy at West Point. -

Reading Publics and Canon Formation in 20Th Century Us Fiction

Copyright by Laura Knowles Wallace 2016 The Dissertation Committee for Laura Knowles Wallace Certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: QUEER NOVELTY: READING PUBLICS AND CANON FORMATION IN 20TH CENTURY US FICTION Committee: Brian Bremen, Supervisor Chad Bennett Ann Cvetkovich Jennifer Wilks Janet Staiger QUEER NOVELTY: READING PUBLICS AND CANON FORMATION IN 20TH CENTURY US FICTION by Laura Knowles Wallace, BA, MA Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin August 2016 Dedication For who else but my students, whose insistent presence served as persistent reminder of the stakes of this project? The many ways contemporary queer readers and critics have invested pre-Stonewall writing and images with romance or nostalgia or distaste all point to the funny communicability of shadow-relations and secret emotions across time, as if they acquire heft only in the long term, where the difficulty of the problems they want to solve (like historical isolation and suffering) can emerge in their full intractability. Christopher Nealon, Foundlings, 2001 I don’t have to wonder whose group I’m in today. Certainly the people who always think the public problem is theirs are gay. Eileen Myles, “To Hell,” Sorry, Tree, 2007 Acknowledgements Thank you to my committee (Brian Bremen, Jennifer Wilks, Chad Bennett, Ann Cvetkovich, and Janet Staiger) for your time, your enthusiasm, and your questions. Thank you to the other faculty members whose teaching and encouragement shaped this project, especially Hannah Wojciehowski, Eric Darnell Pritchard, Mia Carter, and Heather Houser. -

Diane Di Prima

Utah State University DigitalCommons@USU ENGL 6350 – Beat Exhibit Student Exhibits 5-5-2016 Diane Di Prima McKenzie Livingston Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/beat_exhibit Recommended Citation Livingston, McKenzie, "Diane Di Prima" (2016). ENGL 6350 – Beat Exhibit. 2. https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/beat_exhibit/2 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Exhibits at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in ENGL 6350 – Beat Exhibit by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Livingston 1 Diane DiPrima’s Search for a Familiar Truth The image of Diane DiPrima∗ sitting on her bed in a New York flat, eyes cast down, is emblematic of the Beat movement. DiPrima sought to characterize her gender without any constraints or stereotypes, which was no simple task during the 1950s and 1960s. Many of the other Beats, who were predominately male, wrote and practiced varying degrees of misogyny, while DiPrima resisted with her characteristic biting wit. In the early days of her writing (beginning when she was only thirteen), she wrote about political, social, and environmental issues, aligning herself with Timothy Leary’s LSD Experiment in 1966 and later with the Black Panthers. But in the latter half of her life, she shifted focus and mostly wrote of her family and the politics contained therein. Her intention was to find stable ground within her familial community, for in her youth and during the height of the Beat movement, she found greater permanence in the many characters, men and women, who waltzed in and out of her many flats. -

Visit to a Small Planet and the ―Fish out of Water‖ Comedy

Audience Guide Written and compiled by Jack Marshall July 8–August 6, 2011 Theatre Two, Gunston Arts Center Theater you can afford to see— plays you can’t afford to miss! About The American Century Theater The American Century Theater was founded in 1994. We are a professional company dedicated to presenting great, important, but overlooked American plays of the twentieth century . what Henry Luce called ―the American Century.‖ The company’s mission is one of rediscovery, enlightenment, and perspective, not nostalgia or preservation. Americans must not lose the extraordinary vision and wisdom of past playwrights, nor can we afford to surrender our moorings to our shared cultural heritage. Our mission is also driven by a conviction that communities need theater, and theater needs audiences. To those ends, this company is committed to producing plays that challenge and move all Americans, of all ages, origins and points of view. In particular, we strive to create theatrical experiences that entire families can watch, enjoy, and discuss long afterward. These audience guides are part of our effort to enhance the appreciation of these works, so rich in history, content, and grist for debate. The American Century Theater is a 501(c)(3) professional nonprofit theater company dedicated to producing significant 20th Century American plays and musicals at risk of being forgotten. The American Century Theater is supported in part by Arlington County through the Cultural Affairs Division of the Department of Parks, Recreation, and Cultural Resources and the Arlington Commission for the Arts. This arts event is made possible in part by the Virginia Commission on the Arts and the National Endowment for the Arts, as well as by many generous donors. -

Shawyer Dissertation May 2008 Final Version

Copyright by Susanne Elizabeth Shawyer 2008 The Dissertation Committee for Susanne Elizabeth Shawyer certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: Radical Street Theatre and the Yippie Legacy: A Performance History of the Youth International Party, 1967-1968 Committee: Jill Dolan, Supervisor Paul Bonin-Rodriguez Charlotte Canning Janet Davis Stacy Wolf Radical Street Theatre and the Yippie Legacy: A Performance History of the Youth International Party, 1967-1968 by Susanne Elizabeth Shawyer, B.A.; M.A. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin May, 2008 Acknowledgements There are many people I want to thank for their assistance throughout the process of this dissertation project. First, I would like to acknowledge the generous support and helpful advice of my committee members. My supervisor, Dr. Jill Dolan, was present in every stage of the process with thought-provoking questions, incredible patience, and unfailing encouragement. During my years at the University of Texas at Austin Dr. Charlotte Canning has continually provided exceptional mentorship and modeled a high standard of scholarly rigor and pedagogical generosity. Dr. Janet Davis and Dr. Stacy Wolf guided me through my earliest explorations of the Yippies and pushed me to consider the complex historical and theoretical intersections of my performance scholarship. I am grateful for the warm collegiality and insightful questions of Dr. Paul Bonin-Rodriguez. My committee’s wise guidance has pushed me to be a better scholar. -

I Told You So: Gore Vidal Talks Politics Interviews with Jon Weiner OR

I Told you So: Gore Vidal Talks Politics Interviews with Jon Weiner OR Books www.orbooks.com Q. Could you tell us about your formative political experiences? What was the process by which you became a radical? A. I don’t know how I did. I was brought up in an extremely conservative family. The British always want to know what class you belong to. I was asked that on the BBC. I said “I belong to the highest class there is: I’m a third generation celebrity. My grandfather, father, and I have all been on the cover of Time. That’s all there is. You can’t go any higher in America.” The greatest influence on me was my grandfather, Senator Thomas Pryor Gore. That’s his chair. Not from the Senate. From his office. He was blind from the age of ten. He would plot in that chair. He made Wilson president twice rocking away in that thing.! Q. He’s denounced by Teddy Roosevelt in Empire.! A. Yes. T.R. didn’t like anything about him. But T.P.G. was only 36, I think, when he came to the Senate. He was a Populist who finally joined the Democratic Party. They all did. He helped write the constitution of the state of Oklahoma, which is the only socialist state constitution. He was school of Bryan: anti-bank, anti- Eastern, anti-railroads, anti-war. Also anti-black and anti-Jew- what they now call nativist. But he was not a crude figure like Tom Watson or the sainted Huey.