Impact of Alien Insect Pests on Sardinian Landscape and Culture

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Larvae of the Carabidae Genus Dicheirotrichus Jacq. (Coleoptera, Carabidae) from the Fauna of Russia and AGMDFHQW Countries: I

Entomological Review, Vol. 78, No. 2, 1998, pp. 149–163. Translated from Entomologicheskoe Obozrenie, Vol. 77, No. 1, 1998, pp. 134–149. Original Russian Text Copyright © 1998 by Matalin. English Translation Copyright © 1998 by F:BD GZmdZ/Interperiodica Publishing (Russia). Larvae of the Carabidae Genus Dicheirotrichus Jacq. (Coleoptera, Carabidae) from the Fauna of Russia and AGMDFHQW Countries: I. Larvae of the Subgenus Dicheirotrichus Jacq. A. V. Matalin Moscow Pedagogical State University, Moscow, Russia Received October 12, 1996 Abstract—III-instar larvae of Dicheirotrichus ustulatus Dej., II- and III-instar larvae of D. abdominalis Motsch. and D. desertus Motsch. are reported for the first time. All larval instars of D. gustavi Crotch are redescribed. Diagnosis of the subgenus Dicheirotrichus Jacq. and a key to species based on larval characters are given. INTRODUCTION ing the genus composition and relations between its A small, primarily Palaearctic, genus Dicheiro- subgenera. This approach has been successful in clari- trichus Jacq. is represented in the world fauna by fying a number of uncertainties in the taxonomy of the slightly more than 40 species (Kryzhanovskii, 1983). genus Carabus L. (Makarov, 1989). However, little Poor armament of the inner saccus of endophallus has been known on larvae of the genus Dicheiro- combined with the uniform aedeagus structure and, at trichus Jacq. Larvae have been described only for the same time, significant morphological variability D. gustavi Crotch (Shiødte, 1867; Hurka, 1975; Luff, make complicated taxonomic analysis of these species. 1993) of 6 Russian species of the nominotypical sub- The composition of the genus cannot be considered genus; and only for 3 species (Kemner, 1913; Larsson, fixed till now. -

Effect of the Eucalypt Lerp Psyllid Glycaspis Brimblecombei On

DOI: 10.1111/eea.12645 16TH INTERNATIONAL SYMPOSIUM ON INSECT-PLANT RELATIONSHIPS Effect of the eucalypt lerp psyllid Glycaspis brimblecombei on adult feeding, oviposition-site selection, and offspring performance of the bronze bug, Thaumastocoris peregrinus Gonzalo Martınez1,2* ,Andres Gonzalez3 & Marcel Dicke1 1Laboratory of Entomology, Wageningen University, Wageningen, The Netherlands, 2Laboratory of Entomology, National Forestry Research Program, Instituto Nacional de Investigacion Agropecuaria, Tacuarembo, Uruguay, and 3Laboratory of Chemical Ecology, Faculty of Chemistry, Universidad de la Republica, Montevideo, Uruguay Accepted: 5 October 2017 Key words: preference-performance, Thaumastocoridae, Aphalaridae, intraguild competition, Eucalyptus forestry Abstract Oviposition-site selection may be greatly affected by competitive plant-mediated interactions between phytophagous insects but these interactions have been poorly investigated on trees. Here, we evalu- ated the potential interaction between two invasive pests of Eucalyptus trees, the red gum lerp psyllid, Glycaspis brimblecombei Moore (Hemiptera, Sternorrhyncha: Aphalaridae), and the bronze bug, Thaumastocoris peregrinus Carpintero et Dellape (Heteroptera: Thaumastocoridae). We assessed the effect of the co-occurrence of G. brimblecombei on the selection of feeding and oviposition sites by T. peregrinus females using dual-choice bioassays. We compared developmental time and survival of the first instar of nymphs reared on healthy Eucalyptus tereticornis Smith (Myrtaceae) leaves and on leaves infested with the lerp psyllid, either with or without lerps (i.e., white conical sweet-tasting structures, secreted during the nymphal stage). Bronze bug females prefer to oviposit on lerp-carry- ing leaves but we found no difference in feeding preference when compared to healthy leaves. Infesta- tion with the lerp psyllid hampered nymphal performance in terms of developmental time and survival, although the presence of lerps reverted the effect in survival and shortened the duration of the initial instar. -

Cytogenetic Analysis, Heterochromatin

insects Article Cytogenetic Analysis, Heterochromatin Characterization and Location of the rDNA Genes of Hycleus scutellatus (Coleoptera, Meloidae); A Species with an Unexpected High Number of rDNA Clusters Laura Ruiz-Torres, Pablo Mora , Areli Ruiz-Mena, Jesús Vela , Francisco J. Mancebo , Eugenia E. Montiel, Teresa Palomeque and Pedro Lorite * Department of Experimental Biology, Genetics Area, University of Jaén, 23071 Jaén, Spain; [email protected] (L.R.-T.); [email protected] (P.M.); [email protected] (A.R.-M.); [email protected] (J.V.); [email protected] (F.J.M.); [email protected] (E.E.M.); [email protected] (T.P.) * Correspondence: [email protected] Simple Summary: The family Meloidae contains approximately 3000 species, commonly known as blister beetles for their ability to secrete a substance called cantharidin, which causes irritation and blistering in contact with animal or human skin. In recent years there have been numerous studies focused on the anticancer action of cantharidin and its derivatives. Despite the recent interest in blister beetles, cytogenetic and molecular studies in this group are scarce and most of them use only classical chromosome staining techniques. The main aim of our study was to provide new information in Citation: Ruiz-Torres, L.; Mora, P.; Meloidae. In this study, cytogenetic and molecular analyses were applied for the first time in the Ruiz-Mena, A.; Vela, J.; Mancebo, F.J.; family Meloidae. We applied fluorescence staining with DAPI and the position of ribosomal DNA in Montiel, E.E.; Palomeque, T.; Lorite, P. Hycleus scutellatus was mapped by FISH. Hycleus is one of the most species-rich genera of Meloidae Cytogenetic Analysis, but no cytogenetic data have yet been published for this particular genus. -

Download (236Kb)

Chapter (non-refereed) Welch, R.C.. 1981 Insects on exotic broadleaved trees of the Fagaceae, namely Quercus borealis and species of Nothofagus. In: Last, F.T.; Gardiner, A.S., (eds.) Forest and woodland ecology: an account of research being done in ITE. Cambridge, NERC/Institute of Terrestrial Ecology, 110-115. (ITE Symposium, 8). Copyright © 1981 NERC This version available at http://nora.nerc.ac.uk/7059/ NERC has developed NORA to enable users to access research outputs wholly or partially funded by NERC. Copyright and other rights for material on this site are retained by the authors and/or other rights owners. Users should read the terms and conditions of use of this material at http://nora.nerc.ac.uk/policies.html#access This document is extracted from the publisher’s version of the volume. If you wish to cite this item please use the reference above or cite the NORA entry Contact CEH NORA team at [email protected] 110 The fauna, including pests, of woodlands and forests 25. INSECTS ON EXOTIC BROADLEAVED jeopardize Q. borealis here. Moeller (1967) suggest- TREES OF THE FAGACEAE, NAMELY ed that the general immunity of Q. borealis to QUERCUS BOREALIS AND SPECIES OF insect attack in Germany was due to its planting in NOTHOFAGUS mixtures with other Quercus spp. However, its defoliation by Tortrix viridana (green oak-roller) was observed in a relatively pure stand of 743 R.C. WELCH hectares. More recently, Zlatanov (1971) published an account of insect pests on 7 species of oak in Bulgaria, including Q. rubra (Table 35), although Since the early 1970s, and following a number of his lists include many pests not known to occur earlier plantings, it seems that American red oak in Britain. -

Coleoptera, Tenebrionoidea) Del Museu De Ciències Naturals De Barcelona

Arxius de Miscel·lània Zoològica, 14 (2016): 117–216 ISSN: Prieto1698– et0476 al. La colección ibero–balear de Meloidae Gyllenhal, 1810 (Coleoptera, Tenebrionoidea) del Museu de Ciències Naturals de Barcelona M. Prieto, M. García–París & G. Masó Prieto, M., García–París, M. & Masó, G., 2016. La colección ibero–balear de Meloidae Gyllenhal, 1810 (Coleoptera, Tenebrionoidea) del Museu de Ciències Naturals de Barcelona. Arxius de Miscel·lània Zoològica, 14: 117–216. Abstract The Ibero–Balearic collection of Meloidae Gyllenhal, 1810 (Coleoptera, Tenebrionoidea) of the Museu de Ciències Naturals de Barcelona.— A commented catalogue of the Ibero-Balearic collection of Meloidae Gyllenhal, 1810 housed in the Museu de Ciències Naturals de Bar- celona is presented. The studied material consists of 2,129 specimens belonging to 49 of 64 species from the Iberian peninsula and the Balearic Islands. The temporal coverage of the collection extends from the last decades of the nineteenth century to the present time. Revision, documentation, and computerization of the material have been made, resulting in 963 collection records (June 2014). For each lot, the catalogue includes the register number, geographical data, collection date, collector or origin of the collection, and number of specimens. Information about taxonomy and distribution of the species is also given. Chorological novelties are provided, extending the distribution areas for most species. The importance of the collection for the knowledge of the Ibero–Balearic fauna of Meloidae is discussed, particularly concerning the area of Catalonia (northeastern Iberian peninsula) as it accounts for 60% of the records. Some rare or particularly interesting species in the collection are highlighted, as are those requiring protection measures in Spain and Catalonia. -

Disturbance and Recovery of Litter Fauna: a Contribution to Environmental Conservation

Disturbance and recovery of litter fauna: a contribution to environmental conservation Vincent Comor Disturbance and recovery of litter fauna: a contribution to environmental conservation Vincent Comor Thesis committee PhD promotors Prof. dr. Herbert H.T. Prins Professor of Resource Ecology Wageningen University Prof. dr. Steven de Bie Professor of Sustainable Use of Living Resources Wageningen University PhD supervisor Dr. Frank van Langevelde Assistant Professor, Resource Ecology Group Wageningen University Other members Prof. dr. Lijbert Brussaard, Wageningen University Prof. dr. Peter C. de Ruiter, Wageningen University Prof. dr. Nico M. van Straalen, Vrije Universiteit, Amsterdam Prof. dr. Wim H. van der Putten, Nederlands Instituut voor Ecologie, Wageningen This research was conducted under the auspices of the C.T. de Wit Graduate School of Production Ecology & Resource Conservation Disturbance and recovery of litter fauna: a contribution to environmental conservation Vincent Comor Thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of doctor at Wageningen University by the authority of the Rector Magnificus Prof. dr. M.J. Kropff, in the presence of the Thesis Committee appointed by the Academic Board to be defended in public on Monday 21 October 2013 at 11 a.m. in the Aula Vincent Comor Disturbance and recovery of litter fauna: a contribution to environmental conservation 114 pages Thesis, Wageningen University, Wageningen, The Netherlands (2013) With references, with summaries in English and Dutch ISBN 978-94-6173-749-6 Propositions 1. The environmental filters created by constraining environmental conditions may influence a species assembly to be driven by deterministic processes rather than stochastic ones. (this thesis) 2. High species richness promotes the resistance of communities to disturbance, but high species abundance does not. -

Graellsia, 61(2): 225-255 (2005)

Graellsia, 61(2): 225-255 (2005) BIBLIOGRAFÍA Y REGISTROS IBERO-BALEARES DE MELOIDAE (COLEOPTERA) PUBLICADOS HASTA LA APARICIÓN DEL “CATÁLOGO SISTEMÁTICO GEOGRÁFICO DE LOS COLEÓPTEROS OBSERVADOS EN LA PENÍNSULA IBÉRICA, PIRINEOS PROPIAMENTE DICHOS Y BALEARES” DE J. M. DE LA FUENTE (1933) M. García-París1 y José L. Ruiz2 RESUMEN En las publicaciones actuales sobre faunística y taxonomía de Meloidae de la Península Ibérica se citan registros de autores del siglo XIX y principios del XX, uti- lizando como referencia principal las obras de Górriz Muñoz (1882) y De la Fuente (1933). Sin embargo, no se alude a las localidades precisas originales aportadas por otros autores anteriores o coetáneos. Consideramos que el olvido de todas esas citas supone una pérdida importante, tanto por su valor faunístico intrínseco, como por su utilidad para documentar la potencial desaparición de poblaciones concretas objeto de citas históricas, así como para detectar posibles modificaciones en el área de ocupa- ción ibérica de determinadas especies. En este trabajo reseñamos los registros ibéricos de especies de la familia Meloidae que hemos conseguido recopilar hasta la publica- ción del “Catálogo sistemático geográfico de los Coleópteros observados en la Península Ibérica, Pirineos propiamente dichos y Baleares” de J. M. de la Fuente (1933), y discutimos las diferentes posibilidades de adscripción específica cuando la nomenclatura utilizada no corresponde a la actual. Se eliminan del catálogo de espe- cies ibero-baleares: Cerocoma muehlfeldi Gyllenhal, 1817, -

A Genus-Level Supertree of Adephaga (Coleoptera) Rolf G

ARTICLE IN PRESS Organisms, Diversity & Evolution 7 (2008) 255–269 www.elsevier.de/ode A genus-level supertree of Adephaga (Coleoptera) Rolf G. Beutela,Ã, Ignacio Riberab, Olaf R.P. Bininda-Emondsa aInstitut fu¨r Spezielle Zoologie und Evolutionsbiologie, FSU Jena, Germany bMuseo Nacional de Ciencias Naturales, Madrid, Spain Received 14 October 2005; accepted 17 May 2006 Abstract A supertree for Adephaga was reconstructed based on 43 independent source trees – including cladograms based on Hennigian and numerical cladistic analyses of morphological and molecular data – and on a backbone taxonomy. To overcome problems associated with both the size of the group and the comparative paucity of available information, our analysis was made at the genus level (requiring synonymizing taxa at different levels across the trees) and used Safe Taxonomic Reduction to remove especially poorly known species. The final supertree contained 401 genera, making it the most comprehensive phylogenetic estimate yet published for the group. Interrelationships among the families are well resolved. Gyrinidae constitute the basal sister group, Haliplidae appear as the sister taxon of Geadephaga+ Dytiscoidea, Noteridae are the sister group of the remaining Dytiscoidea, Amphizoidae and Aspidytidae are sister groups, and Hygrobiidae forms a clade with Dytiscidae. Resolution within the species-rich Dytiscidae is generally high, but some relations remain unclear. Trachypachidae are the sister group of Carabidae (including Rhysodidae), in contrast to a proposed sister-group relationship between Trachypachidae and Dytiscoidea. Carabidae are only monophyletic with the inclusion of a non-monophyletic Rhysodidae, but resolution within this megadiverse group is generally low. Non-monophyly of Rhysodidae is extremely unlikely from a morphological point of view, and this group remains the greatest enigma in adephagan systematics. -

Grasshoppers and Locusts (Orthoptera: Caelifera) from the Palestinian Territories at the Palestine Museum of Natural History

Zoology and Ecology ISSN: 2165-8005 (Print) 2165-8013 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/tzec20 Grasshoppers and locusts (Orthoptera: Caelifera) from the Palestinian territories at the Palestine Museum of Natural History Mohammad Abusarhan, Zuhair S. Amr, Manal Ghattas, Elias N. Handal & Mazin B. Qumsiyeh To cite this article: Mohammad Abusarhan, Zuhair S. Amr, Manal Ghattas, Elias N. Handal & Mazin B. Qumsiyeh (2017): Grasshoppers and locusts (Orthoptera: Caelifera) from the Palestinian territories at the Palestine Museum of Natural History, Zoology and Ecology, DOI: 10.1080/21658005.2017.1313807 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/21658005.2017.1313807 Published online: 26 Apr 2017. Submit your article to this journal View related articles View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=tzec20 Download by: [Bethlehem University] Date: 26 April 2017, At: 04:32 ZOOLOGY AND ECOLOGY, 2017 https://doi.org/10.1080/21658005.2017.1313807 Grasshoppers and locusts (Orthoptera: Caelifera) from the Palestinian territories at the Palestine Museum of Natural History Mohammad Abusarhana, Zuhair S. Amrb, Manal Ghattasa, Elias N. Handala and Mazin B. Qumsiyeha aPalestine Museum of Natural History, Bethlehem University, Bethlehem, Palestine; bDepartment of Biology, Jordan University of Science and Technology, Irbid, Jordan ABSTRACT ARTICLE HISTORY We report on the collection of grasshoppers and locusts from the Occupied Palestinian Received 25 November 2016 Territories (OPT) studied at the nascent Palestine Museum of Natural History. Three hundred Accepted 28 March 2017 and forty specimens were collected during the 2013–2016 period. -

Bosco Palazzi

SHILAP Revista de Lepidopterología ISSN: 0300-5267 ISSN: 2340-4078 [email protected] Sociedad Hispano-Luso-Americana de Lepidopterología España Bella, S; Parenzan, P.; Russo, P. Diversity of the Macrolepidoptera from a “Bosco Palazzi” area in a woodland of Quercus trojana Webb., in southeastern Murgia (Apulia region, Italy) (Insecta: Lepidoptera) SHILAP Revista de Lepidopterología, vol. 46, no. 182, 2018, April-June, pp. 315-345 Sociedad Hispano-Luso-Americana de Lepidopterología España Available in: https://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=45559600012 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System Redalyc More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America and the Caribbean, Spain and Journal's webpage in redalyc.org Portugal Project academic non-profit, developed under the open access initiative SHILAP Revta. lepid., 46 (182) junio 2018: 315-345 eISSN: 2340-4078 ISSN: 0300-5267 Diversity of the Macrolepidoptera from a “Bosco Palazzi” area in a woodland of Quercus trojana Webb., in southeastern Murgia (Apulia region, Italy) (Insecta: Lepidoptera) S. Bella, P. Parenzan & P. Russo Abstract This study summarises the known records of the Macrolepidoptera species of the “Bosco Palazzi” area near the municipality of Putignano (Apulia region) in the Murgia mountains in southern Italy. The list of species is based on historical bibliographic data along with new material collected by other entomologists in the last few decades. A total of 207 species belonging to the families Cossidae (3 species), Drepanidae (4 species), Lasiocampidae (7 species), Limacodidae (1 species), Saturniidae (2 species), Sphingidae (5 species), Brahmaeidae (1 species), Geometridae (55 species), Notodontidae (5 species), Nolidae (3 species), Euteliidae (1 species), Noctuidae (96 species), and Erebidae (24 species) were identified. -

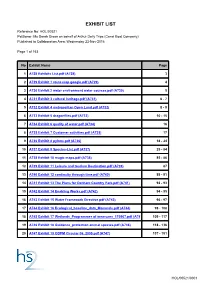

Exhibit List

EXHIBIT LIST Reference No: HOL/00521 Petitioner: Ms Sarah Green on behalf of Arthur Daily Trips (Canal Boat Company) Published to Collaboration Area: Wednesday 23-Nov-2016 Page 1 of 163 No Exhibit Name Page 1 A728 Exhibits List.pdf (A728) 3 2 A729 Exhibit 1 route map google.pdf (A729) 4 3 A730 Exhibit 2 water environment water courses.pdf (A730) 5 4 A731 Exhibit 3 cultural heritage.pdf (A731) 6 - 7 5 A732 Exhibit 4 metropolitan Open Land.pdf (A732) 8 - 9 6 A733 Exhibit 5 dragonflies.pdf (A733) 10 - 15 7 A734 Exhibit 6 quality of water.pdf (A734) 16 8 A735 Exhibit 7 Customer activities.pdf (A735) 17 9 A736 Exhibit 8 pylons.pdf (A736) 18 - 24 10 A737 Exhibit 9 Species-List.pdf (A737) 25 - 84 11 A738 Exhibit 10 magic maps.pdf (A738) 85 - 86 12 A739 Exhibit 11 Leisure and tourism Destination.pdf (A739) 87 13 A740 Exhibit 12 continuity through time.pdf (A740) 88 - 91 14 A741 Exhibit 13 The Plans for Denham Country Park.pdf (A741) 92 - 93 15 A742 Exhibit 14 Enabling Works.pdf (A742) 94 - 95 16 A743 Exhibit 15 Water Framework Directive.pdf (A743) 96 - 97 17 A744 Exhibit 16 Ecological_baseline_data_Mammals.pdf (A744) 98 - 108 18 A745 Exhibit 17 Wetlands_Programmes of measures_170907.pdf (A745) 109 - 117 19 A746 Exhibit 18 Guidance_protection animal species.pdf (A746) 118 - 136 20 A747 Exhibit 19 ODPM Circular 06_2005.pdf (A747) 137 - 151 HOL/00521/0001 EXHIBIT LIST Reference No: HOL/00521 Petitioner: Ms Sarah Green on behalf of Arthur Daily Trips (Canal Boat Company) Published to Collaboration Area: Wednesday 23-Nov-2016 Page 2 of 163 No Exhibit -

Diversity of the Moth Fauna (Lepidoptera: Heterocera) of a Wetland Forest: a Case Study from Motovun Forest, Istria, Croatia

PERIODICUM BIOLOGORUM UDC 57:61 VOL. 117, No 3, 399–414, 2015 CODEN PDBIAD DOI: 10.18054/pb.2015.117.3.2945 ISSN 0031-5362 original research article Diversity of the moth fauna (Lepidoptera: Heterocera) of a wetland forest: A case study from Motovun forest, Istria, Croatia Abstract TONI KOREN1 KAJA VUKOTIĆ2 Background and Purpose: The Motovun forest located in the Mirna MITJA ČRNE3 river valley, central Istria, Croatia is one of the last lowland floodplain 1 Croatian Herpetological Society – Hyla, forests remaining in the Mediterranean area. Lipovac I. n. 7, 10000 Zagreb Materials and Methods: Between 2011 and 2014 lepidopterological 2 Biodiva – Conservation Biologist Society, research was carried out on 14 sampling sites in the area of Motovun forest. Kettejeva 1, 6000 Koper, Slovenia The moth fauna was surveyed using standard light traps tents. 3 Biodiva – Conservation Biologist Society, Results and Conclusions: Altogether 403 moth species were recorded Kettejeva 1, 6000 Koper, Slovenia in the area, of which 65 can be considered at least partially hygrophilous. These results list the Motovun forest as one of the best surveyed regions in Correspondence: Toni Koren Croatia in respect of the moth fauna. The current study is the first of its kind [email protected] for the area and an important contribution to the knowledge of moth fauna of the Istria region, and also for Croatia in general. Key words: floodplain forest, wetland moth species INTRODUCTION uring the past 150 years, over 300 papers concerning the moths Dand butterflies of Croatia have been published (e.g. 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8).