Freshwater Scottish Loch Settlements of The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Line of March

NYC TARTAN DAY PARADE - April 9, 2016 LINE OF MARCH FIRST DIVISION: West 44th Street from 6th Avenue to 5th Avenue Section 1: Forms from corner of 6th Avenue East to 59 West 44th Street 1. NYC Police Department Mounted Unit (forms on 6th Avenue above W. 45th Street) 2. U.S. Military Academy (West Point) Pipes and Drums 3. Grand Marshal Banner 4. Grand Marshal Sam Heughan (with family/friends ) 5. St. Andrew’s Color Guard 6. NTDNYC Banner 7. Edinburgh Academy Pipe and Drum Band 8. National Tartan Day New York Parade Committee 9. BARBOUR 10. U.S. Naval Academy (Annapolis) Pipes and Drums 11. Scottish American Military Society Color Guard 12. VIPs: Hon. Tricia Marwick, MSP; Fergus Cochrane 13. Scottish Parliament/Politicians/U.S. Politicians 14. Visit Scotland Section 2: Forms from 59 West 44th Street to 37 West 44th Street 1. Mt. Kisco Scottish Pipes and Drums 2. St. Andrew’s Society of New York 3. New York Caledonian Club Pipe Band 4. New York Caledonian Club 5. New York Metro Pipe Band 6. American Scottish Foundation 7. Tri-County Pipes and Drums 8. Clan Fraser 9. Clan Ross 10. St. Andrew’s Society; City of Albany 11. Pipes and Drums of the Atlantic Watch 12. Daughters of Scotia - 1 - Section 2: Continued 13. Daughters of the British Empire 14. Clan Abernathy of Richmond 15. CARNEGIE HALL Section 3: Forms from 37 West 44th Street to 27 West 44th Street 1. NYC Police Department Marching Band 2. Clan Malcolm/Macallum 3. Clan MacIneirghe 4. Long Island Curling Club 5. -

Colonel Arren Calvin Buchanan, Jr. INTERVIEWER

INSTITUTE OF TEXAN CULTURES ORAL HISTORY PROGRAM INTERVIEW WITH: Colonel Arren Calvin Buchanan, Jr. INTERVIEWER: Jim Sweeney DATE: January 19, 1985 PLACE: Air Force Village, San Antonio, Texas TITLE: The Scots in Texas Clan Buchanan (Society in America, Inc.) [Music is playing at the beginning of the tape: bagpipes.) S: Colonel Buchanan, I understand you are of Scottish descent and also a third generation Texan. Now that's quite a combination. Would you mind telling us a little bit about that? B: Yes, I'll be happy to, Jim. My great-grandfather, James Buchanan of Alabama, came with Stephen F. Austin's fifth colony, 1835, to what became Washington-on-the-Brazos. He was a farmer and built a log cabin down in Montgomery County. And he then was drafted into the Texas Army with General Sam Houston; and was subsequently killed in the Battle of the Alamo. And you will find his name, James Buchanan, of Alabama, on the north wall of the Alamo. His widow was given a grant of l a nd in 1844 by the Republic of Texas; and the grant was signed by Presiden t Sam Houston. My father was born on this grant of land, below Caldwe ll, in 1862, the son of James Houston Buchanan, BUCHANAN 2 B: the grandson of James Buchanan. So, therefore, we have roots that go back into early Texas history. Many of the Stephen F. Austin's colonists, as you see this was the fifth colony, were Scottish that carne across from the Ea st Coast. Another important colony which should be mentioned is the Sterling C. -

Tourist Map of Scotland

Hermaness Nat. Keen of Hamar Reserve Nat. Reserve seal Lumbister RSPB Reserve Feltar RSPB Reserve otter mytouristmaps Scotland seal Lerwick Shetland Islands Sumburgh seal Atlantic Orkneys Islands Ocean seal Vat of Kirbuster Skara Brae Balfour Castle Ring of Brodgar Kirkwall map legend Stromness whale Cape Wrath Thurso Durness John O’ Groats seal puffin Flannan Smoo Cave seal Isles Sandwoodway Bay Isle of Lewis& The Wick Harris Blackhouse Whaligoe Steps Garenin Stornoway Old Man of Lybster Stoer seal deer Loch The Callanish Glencoul Standing Stones basking seal shark Helmsdale Inverpolly Nature Northern Sea Reserve Summer Lairg Scarp Isles peregrine Dunrobin Castle Rhenigidale Ullapool falcon Dornoch Alladale The Wilderness Tain dolphin RSPB Quiraing Loch Reserve Balranald Maree Fraserburgh Berneray bottlenose Bow Fiddle dolphin Rock seal Gairloch Pennan Portsoy otter Findhorn Glen Fordyce Fairy Kilt Rock Torridon Lochmaddy Culbin Forest North Uist Glen Fort George Peterhead seal Old Man of Strathpeffer Storr Inverness Great Haddo House Benbecula Dunvegan Raasay Glen Way Fyvie Castle Plockton golden Aberlour Waterstein Isle of eagle Loch Druidibeag Head Skye Nat. Reserve Scalpay Glen Affric Kyle of Lochalsh wildcat Gleann Lichd South Uist Broadford Glenmore Forest Loch Kildrummy Lochboisdale Eilean Donan Glen Park Castle Shiel Ness Aviemore Loch Morlich Castle Tomintoul Craigievar Castle Fraser Castle dolphin Fort Augustus Aberdeen Canna Cuillin Cairngorms Lecht Hills Pass Crathes Castle Eriskay Newtonmore Mountain Small crosbill Railway Isles Mallaigh Cairngorms Ballater Barra red squirrel National Park Rum Braemar Glen pine Dunnottar Castle Roy marten Eigg osprey Linn of Dee Muck Fort William Ben Nevis Glenshee (1345m) Blair Castle A93 Loch Rannoch Isle of Coll Kilchoan Highland Titles Glencoe Nat. -

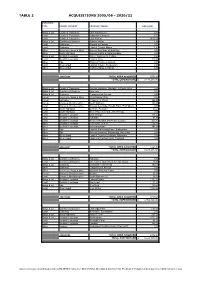

Table 2-Acquisitions (Web Version).Xlsx TABLE 2 ACQUISITIONS 2005/06 - 2020/21

TABLE 2 ACQUISITIONS 2005/06 - 2020/21 PURCHASE TYPE FOREST DISTRICT PROPERTY NAME AREA (HA) Bldgs & Ld Cowal & Trossachs Edra Farmhouse 2.30 Land Cowal & Trossachs Ardgartan Campsite 6.75 Land Cowal & Trossachs Loch Katrine 9613.00 Bldgs & Ld Dumfries & Borders Jufrake House 4.86 Land Galloway Ground at Corwar 0.70 Land Galloway Land at Corwar Mains 2.49 Other Inverness, Ross & Skye Access Servitude at Boblainy 0.00 Other North Highland Access Rights at Strathrusdale 0.00 Bldgs & Ld Scottish Lowlands 3 Keir, Gardener's Cottage 0.26 Land Scottish Lowlands Land at Croy 122.00 Other Tay Rannoch School, Kinloch 0.00 Land West Argyll Land at Killean, By Inverary 0.00 Other West Argyll Visibility Splay at Killean 0.00 2005/2006 TOTAL AREA ACQUIRED 9752.36 TOTAL EXPENDITURE £ 3,143,260.00 Bldgs & Ld Cowal & Trossachs Access Variation, Ormidale & South Otter 0.00 Bldgs & Ld Dumfries & Borders 4 Eshiels 0.18 Bldgs & Ld Galloway Craigencolon Access 0.00 Forest Inverness, Ross & Skye 1 Highlander Way 0.27 Forest Lochaber Chapman's Wood 164.60 Forest Moray & Aberdeenshire South Balnoon 130.00 Land Moray & Aberdeenshire Access Servitude, Raefin Farm, Fochabers 0.00 Land North Highland Auchow, Rumster 16.23 Land North Highland Water Pipe Servitude, No 9 Borgie 0.00 Land Scottish Lowlands East Grange 216.42 Land Scottish Lowlands Tulliallan 81.00 Land Scottish Lowlands Wester Mosshat (Horberry) (Lease) 101.17 Other Scottish Lowlands Cochnohill (1 & 2) 556.31 Other Scottish Lowlands Knockmountain 197.00 Other Tay Land at Blackcraig Farm, Blairgowrie -

Wester Ross Ros An

Scottish Natural Heritage Explore for a day Wester Ross Ros an lar Wester Ross has a landscape of incredible beauty and diversity Historically people have settled along the seaboard, sustaining fashioned by a fascinating geological history. Mountains of strange, themselves by combining cultivation and rearing livestock with spectacular shapes rise up from a coastline of diverse seascapes. harvesting produce from the sea. Crofting townships, with their Wave battered cliffs and crevices are tempered by sandy beaches small patch-work of in-bye (cultivated) fields running down to the or salt marsh estuaries; fjords reach inland several kilometres. sea can be found along the coast. The ever changing light on the Softening this rugged landscape are large inland fresh water lochs. landscape throughout the year makes it a place to visit all year The area boasts the accolade of two National Scenic Area (NSA) round. designations, the Assynt – Coigach NSA and Wester Ross NSA, and three National Nature Reserves; Knockan Crag, Corrieshalloch Symbol Key Gorge and Beinn Eighe. The North West Highland Geopark encompasses part of north Wester Ross. Parking Information Centre Gaelic dictionary Paths Disabled Access Gaelic Pronunciation English beinn bayn mountain gleann glyown glen Toilets Wildlife watching inbhir een-er mouth of a river achadh ach-ugh field mòr more big beag bake small Refreshments Picnic Area madainn mhath mat-in va good morning feasgar math fess-kur ma good afternoon mar sin leat mar shin laht goodbye Admission free unless otherwise stated. 1 11 Ullapool 4 Ullapul (meaning wool farm or Ulli’s farm) This picturesque village was founded in 1788 as a herring processing station by the British Fisheries Association. -

Balquhidder General Register of the Poor 1889-1929 (PR/BQ/4/1)

Balquhidder General Register of the Poor 1889-1929 (PR/BQ/4/1) 1st Surname 2nd Surname Forename(s) Gender Age Place of Origin Date of Entry Residence Status Occupation Bain Morris Elizabeth F 51 Kilmadock 1920, 27 Jul Toll House, Glenogle Widow House duties Braid Jane Isabella F 54 Dundurer Mill, Comrie 1912, 23 Feb 5 Eden St, Dundee Single House servant Cameron Alexander M 70 Balquhidder 1917, 7 Dec Kipp Farm, Strathyre Single Farmer Campbell Janet F 48 Balquhidder 1915, 7 Dec Stronvar, Balquhidder Single Outworker Campbell Annie F 44 Balquhidder 1909, 15 Mar Black Island Cottages, Stronvar Single Outdoor worker Campbell Ann F 40 Balquhidder 1905 Black Island Cottages, Stronvar Single Domestic Campbell McLaren Janet F 61 Balquhidder 1903, 6 Jun Strathyre Single Servant Campbell Colin M 20 Comrie 27 Aug ? Edinchip Single Farm servant Carmichael Frederick M 48 Liverpool 1919, 7 May Poorhouse Single Labourer Carmichael Ferguson Janet F 72 Balquhidder 1904, 9 Dec Strathyre Widow Domestic Christie Lamont Catherine F 27 Ballycastle, Ireland 1891, 16 Dec Stirling District Asylum Married Currie McLaren Margaret F 43 Kirkintilloch 1910, 29 Jul Newmains, Wishaw Widow House duties Dewar James M 38 Balquhidder 1913, 10 Dec Post Office, Strathyre Single Grocer & Postmaster Ferguson Janet F 77 Balquhidder 1927, 26 May Craigmore, Strathyre Single House duties Ferguson Janet F 53 Aberfoyle 1913, 6 May Stronvar, Balquhidder Widow Charwoman & Outworker Ferguson John M 52 Balquhidder 1900, 9 Jul Govan Asylum Single Hotel Porter Ferguson Minnie F 11 Dumbarton -

James Hawkins 2009 the Chronicles of the Straight Line Ramblers Club

The Chronicles of the Straight Line Ramblers Club James Hawkins 2009 The Chronicles of the Straight Line Ramblers Club James Hawkins SW1 GALLERY 12 CARDINAL WALK LONDON SW1E 5JE James and Flick Hawkins would like to thank The John Muir Trust (www.jmt.org) and Knoydart Foundation (www.knoydart-foundation.com) for their support Design Peter A Welch (www.theworkhaus.com) MAY 2009 Printed J Thomson Colour Printers, Inverness, IV3 8GY The Straight Line Ramblers Club Don’t get me wrong, I am most enthusiastic about technology and its development; I am very happy to be writing this on my new PC that also helps me enormously with many aspects of my visual work. No it is more that, in our long evolution, at this point there now seems a danger of disconnection from The Straight Line Ramblers Club was first conceived when we were teenagers walking our parents the natural world. We have always been controlled by Nature, now we think that we can control it. dogs around the Oxfordshire countryside, membership was flexible, anyone could join and of course the one thing we didn’t do was walk in a straight line. Many of us have kept in touch and when John Muir, whose writings I have discovered during the research for this exhibition, felt that he needed we meet up that spirit of adventure still prevails, there aren’t any rules, but if there were they would to experience the wilderness “to find the Law that governs the relations subsisting between human be that spontaneity is all, planned routes exist to be changed on a whim and that its very impor- beings and Nature.” After many long and often dangerous journeys into wild places he began to tant to see what’s around the next corner or over the next top. -

A New Chronology for Crannogs in North-East Scotland. Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland, 147, Pp

Stratigos, M. J. and Noble, G. (2018) A new chronology for crannogs in north-east Scotland. Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland, 147, pp. 147-173. (doi:10.9750/PSAS.147.1254) There may be differences between this version and the published version. You are advised to consult the publisher’s version if you wish to cite from it. http://eprints.gla.ac.uk/165849/ Deposited on: 25 July 2018 Enlighten – Research publications by members of the University of Glasgow http://eprints.gla.ac.uk This is the peer-reviewed, revised but unedited version of an article which will be published by the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland. A new chronology for crannogs in north-east Scotland Michael J Stratigos and Gordon Noble ABSTRACT This article presents the results of a programme of investigation which aimed to construct a more detailed understanding of the character and chronology of crannog occupation in north- east Scotland, targeting a series of sites across the region. The emerging pattern revealed through targeted fieldwork in the region shows broad similarities to the existing corpus of data from crannogs in other parts of the country. Crannogs in north-east Scotland now show evidence for origins in the Iron Age. Further radiocarbon evidence has emerged from crannogs in the region revealing occupation during the 9th–10th centuries ad, a period for which there is little other settlement evidence in the area. Additionally, excavated contexts dated to the 11th–12th centuries and historic records suggest that the tradition of crannog dwelling continued into the later medieval period. -

Argyll Bird Report with Sstematic List for the Year

ARGYLL BIRD REPORT with Systematic List for the year 1998 Volume 15 (1999) PUBLISHED BY THE ARGYLL BIRD CLUB Cover picture: Barnacle Geese by Margaret Staley The Fifteenth ARGYLL BIRD REPORT with Systematic List for the year 1998 Edited by J.C.A. Craik Assisted by P.C. Daw Systematic List by P.C. Daw Published by the Argyll Bird Club (Scottish Charity Number SC008782) October 1999 Copyright: Argyll Bird Club Printed by Printworks Oban - ABOUT THE ARGYLL BIRD CLUB The Argyll Bird Club was formed in 19x5. Its main purpose is to play an active part in the promotion of ornithology in Argyll. It is recognised by the Inland Revenue as a charity in Scotland. The Club holds two one-day meetings each year, in spring and autumn. The venue of the spring meeting is rotated between different towns, including Dunoon, Oban. LochgilpheadandTarbert.Thc autumn meeting and AGM are usually held in Invenny or another conveniently central location. The Club organises field trips for members. It also publishes the annual Argyll Bird Report and a quarterly members’ newsletter, The Eider, which includes details of club activities, reports from meetings and field trips, and feature articles by members and others, Each year the subscription entitles you to the ArgyZl Bird Report, four issues of The Eider, and free admission to the two annual meetings. There are four kinds of membership: current rates (at 1 October 1999) are: Ordinary E10; Junior (under 17) E3; Family €15; Corporate E25 Subscriptions (by cheque or standing order) are due on 1 January. Anyonejoining after 1 Octoberis covered until the end of the following year. -

A Walking Guide to Inchcailloch Innis Cailleach Leabhar-I�Il Do Luchd-Coiseachd

A walking guide to Inchcailloch Innis Cailleach leabhar-iil do luchd-coiseachd Please give this leaflet back to the visitor centre when you have finished with it! A jewel in Loch Lomond Seud ann an Loch Laomainn lochlomond-trossachs.org Welcome to Inchcailloch Discover how dramatic natural forces and The Summit Path is more strenuous with a steep years of human use have combined to climb to the top of the island. Here you’ll find out how dramatic forces of nature have sculpted the create an island of remarkable diversity. island and created lots of different homes for plants There are two walking routes and animals. on the island – the Low Path You can visit the island all year and the Summit Path. They round weather permitting. can be enjoyed separately or If you don’t have your own boat, together. Stopping points you can be taken there from are marked with numbered Balmaha or Luss by one of the posts on each path which ferry services. More information relate to the sections in this is on the Inchcailloch section Walking Guide. The points run of our website. consecutively from one path to the other. Each path takes 30- The wooded island of Inchcailloch 45 minutes, but take your time is a gem in the loch and part of and enjoy the view. Loch Lomond National Nature Reserve. Loch Lomond & The The Low Path is a gentle Trossachs National Park Authority woodland walk with a few manages the island for people slopes. At first sight the woods and nature. -

Arbon, Anthony Lyle PRG 1190/11 Special List ______

___________________________________________________________________ Arbon, Anthony Lyle PRG 1190/11 Special List ___________________________________________________________________ Outsize illustrations of ships 750 illustrations from published sources. These illustrations are not duplicated in the Arbon-Le Maiste collection. Sources include newspaper cuttings and centre-spreads from periodicals, brochures, calendar pages, posters, sketches, plans, prints, and other reproductions of artworks. Most are in colour. Please note the estimated date ranges relate to the ships illustrated, not year of publication. See Series 11/14 for Combined select index to Series 11 arranged alphabetically by ships name. REQUESTING ITEMS: Please provide both ships name and full location details. Unnumbered illustrations are filed in alphabetical order under the name of the first ship mentioned in the caption. ___________________________________________________________________ 1. Illustrations of sailing ships. c1780-. 230 illustrations. Arranged alphabetically by name of ship. 2. Illustrations mainly of ocean going motor powered ships. Excludes navy vessels (see Series 3,4 & 5) c1852- 150 illustrations. Merchant shipping, including steamships, passenger liners, cargo vessels, tankers, container ships etc. Includes a few river steamers and paddleboats. Arranged alphabetically by name of ship. 3. Illustrations of Australian warships. c1928- 21 illustrations Arranged alphabetically by name of ship. 4. Australian general naval illustrations, including warship badges, -

Boisdale of Canary Wharf Whisky Bible

BOISDALE Boisdale of Canary Wharf Whisky Bible 1 All spirits are sold in measures of 25ml or multiples thereof. All prices listed are for a large measure of 50ml. Should you require a 25ml measure, please ask. All whiskies are subject to availability. 1. Springbank 10yr 19. Old Pulteney 12yr 37. Ardbeg Corryvreckan 55. Longmorn 16yr 2. Highland Park 12yr 20. Aberfeldy 12yr 38. Smokehead 56. Glenrothes Select Reserve 3. Bowmore 12yr 21. Blair Athol 12yr 39. Lagavulin 16yr 57. Glenfiddich 15yr Solera 4. Oban 14yr 22. Royal Lochnagar 12yr 40. Laphroaig Quarter Cask 58. Glenfarclas 10yr 5. Cragganmore 12yr 23. Talisker 10yr 41. Laphroaig 10yr 59. Ben Nevis 12yr 6. Fettercairn (Old) 10yr 24. Laphroaig 15yr 42. Octomore 7.1 60. Highland Park 18yr 7. Benromach 10yr 25. Benriach Curiositas 10yr 43. Tomintoul 16yr 61. Glenfarclas 40yr 105 8. Ardmore Traditional 26. Caol Ila 12yr 44. Glengoyne 10yr 62. Macallan 10yr Sherry Oak 9. Connemara Peated 27. Port Charlotte 2008 45. Cardhu 12yr 63. Glendronach 12yr 10. St. George’s Chapter 9 28. Loch Lomond 12yr 46. An Cnoc 16yr 64. Balvenie 12yr DoubleWood 11. Isle of Jura 10yr 29. Speyburn 10yr 47. Glenkinchie 12yr 65. Aberlour 10yr 12. Glen Garioch 21yr 30. Balblair 1997 48. Macallan 12yr Fine Oak 66. Glengoyne 12yr 13. Tobermory 10yr 31. Bruichladdie Classic 49. Glenfiddich 12yr 67. Penderyn Madeira 14. Dalwhinnie 15yr Laddie 50. Bushmills 10yr 68. Glen Moray 12yr 15. Glenmorangie Original 32. Tullibardine 223 51. Tomatin 12yr 69. Glen Grant 10yr 16. Bunnahabhain 12yr 33. Tomatin 18yr 52. Glenlivet 12yr 70.