Isabelle Le Minh Not the End

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Light Rail Potential in Rochester, New York

TRB Special Report 195 73 Light Rail Potential in Rochester, New York SIGURD GRAVA, Parsons Brinckerhoff Quade & Douglas, Inc. The development of public transit in the United States is farebox revenues exceeded operating expenses in only one again at a crossroads. The administration in Washington year (1943). Patronage peaked at 5 million in 1949, but slid has made policy statements and begun to implement pro- to about a million in the mid-1950s. By then the line was grammatic changes that significantly differ or diametri- becoming dilapidated because of deferred maintenance; cally oppose trends that dominated the recent past. What after disputes between the city and the corporation as to the future holds, or what adjustments will be required to financial responsibility, service was discontinued in 1956 existing transit services and to plans for system expansion, (the year of the Interstate Highway Act). is uncertain. it is clear, however, that a turning point has For several decades thereafter, the "ditch" in been reached. Light rail is regarded differently than heavy Rochester stayed in the memories of transit specialists and rail or buses. Heavy rail is in considerable disfavor planners: "Shouldn't the service be reactivated?" "What because of high capital costs; buses are in favor because are they going to do with it?" A partial, although negative, they are simple and responsive; light rail is left somewhere answer was provided in the context of the highway building in the middle. A recently "discovered' mode, light rail boom that swept the nation in the 1960s. Rochester is one does not have the documented use in North America to of the few cities in the United States that actually built a allow nondebatable forecasts and estimates of its merits. -

Closure of the Kodak Plant in Rochester, United States Lessons from Industrial Transitions

Closure of the Kodak plant in Rochester, United States Lessons from industrial transitions SEI brief Key insights: June 2021 • Rochester went through a decades-long process of industrial transition as the Eastman Kodak Company, a photography technology company, cut more than 80% of its jobs from Aaron Atteridge its height in the 1980s to its bankruptcy in 2012. Claudia Strambo • Rochester emerged from the transition with a more diverse economy, and with higher levels of employment. Key to this positive outcome was the city’s use of the existing infrastructure and skill set to reorient the regional economy and enable the development of new tech companies. • Universities and major cultural institutions supported the transition by attracting research funding and companies seeking high-skilled workers, and by collaborating with the private sector to develop training programs that matched the skills companies needed. • Even as the economy has grown, however, the city centre has suffered from population loss and urban decay. Acute inequalities remain: new employment opportunities mainly benefitted high-skill workers, and the quality of jobs, in terms of wages and security, has decreased. • In an industrial transition, it is important to implement measures to specifically address poverty and marginalization, and to ensure broader economic diversification, as well as use a broad set of indicators when assessing the effectiveness of transition policies. This case study examines the decline and ultimately closure of the Kodak plant in Rochester, New York, United States. It is part of a series that looks at four historical cases involving the decline of major industrial or mining activities. -

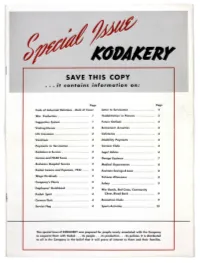

KODAKERY Was Prepared for People Newly Associated with the Company to Acquaint Them with Kodak

I SAVE THIS COPY ... it contains information on: Page Page ... Code of Industrial Relations ... .Back of Cover Letter to Servicemen ............ ... ................. 4 War Production ................................. ...... l 'K o d a k flv1fles. I '"• p·JCtures ......... .............. Suggestion System .............. ............ .. ....... l Future Outlook .......................... .. ........... 6 V 1s1flng Nurses .... ................................ ..... 2 Retirement Annuities ............................. 6 Life Insurance ..................... ............ .. ...... 2 Cafeterias .... ...................................... ..... 6 Vacations .. .................. .... .. .............. ....... 2 Disability Payments ............................... 6 Payments to Servicemen ..... .................... 2 Camera Clubs ............................ .. ........... 6 Kodakers in Service ................................. 2 Legal Advice ......... ....... ............. .. ... ......... 6 Income and FOAB Taxes .................. ....... 2 George Eastman ...... .......... ..................... 7 Rochester Hospital Service ................ ..... 2 Medical Departments .............. ............... 8 Kodak Income and Expenses, 1944 ... .... 3 Eastman Savings & Loan ......................... 8 Wage Dividends ..................................... 3 Sickness Allowance .................. ............... 8 Company's Plants ............................ .... ... 3 Safety ...................................... ... ............ 9 Employees' Guidebook ............ -

125 Years of Rochester's Parks by Katie Eggers Comeau

ROCHESTER HISTORY by Katie Eggers Comeau Vol. 75 Fall 2013 No. 2 -nooo A Publication of the Central Library of Rochester and Monroe County This aerial view postcard from the middle ofthe twentieth centuryportrays Highland Park during the full bloom oflilac season. From the Rochester Public Library Local History & Genealogy Division. Front Cover: An undated postcard from Seneca Park. Rochesterians can be seen strolling around in "pleasure ground" fashion, precisely as architect Frederick Law Olmsted envisioned. From the Rochester Public Library Local History & Genealogy Division. ROCHESTER HISTORY STAFF EDITOR: Christine L. Ridarsky ASSISTANT EDITOR: Jeff Ludwig LAYOUT AND DESIGN: Inge Munnings EDITORIAL BOARD dannj. Broyld Timothy Kneeland Central Connecticut State University Nazareth College Michelle Finn Christine L. Ridarsky Deputy City Historian City Historian/Rochester Public Library Jennifer Gkourlias Verdis Robinson Young Women's College Prep Charter School Monroe Community College Michelle Inclema Shippers Victoria Schmitt Messenger Post Media Corn Hill Navigation Leatrice M. Kemp Carolyn Vacca Rochester Museum & Science Center St. John Fisher College/Monroe County Historian Dear Rochester History Reader, Rochester has long held a reputation among its peer cities for bold visions that blend business and civic ventures. In this issue of Rochester History, Katie Eggers Comeau explores one of the bolder choices in the history of our city: choosing to make public space a priority. Eggers Comeau traces the vibrant history of Rochester's parks, from the early days of Genesee Valley and Seneca parks, to the more recent developments of Tryon Park and El Camino Trail, revealing the passion and creativity of park designers and caretakers. -

SURVEY of DOWNTOWN OFFICE SPACE June 2018

SURVEY OF DOWNTOWN OFFICE SPACE June 20 18 ROCHESTER DOWNTOWN DEVELOPMENT CORPORATION 100 Chestnut Street, Suite 1910 ~ Rochester, New York 14604 (585) 546-6920 ~ (585) 546-4784 (fax) [email protected] ~ www.rochesterdowntown.com ~ The Rochester Downtown Development Corporation’s SURVEY OF DOWNTOWN OFFICE SPACE, June 2018 Executive Summary RDDC tracks nearly every building located in the downtown market, defined as everything within what was the Inner Loop plus High Falls, Upper East End, and Alex Park. Downtown’s commercial building inventory contains the region’s oldest office structures as well as its newest towers. This year, RDDC is tracking 9.7 million square feet in 117 office buildings. Of these, 89 are competitive buildings totaling 6.7 million square feet – 69% of all downtown space. KEY RESULTS As in 2017, the 2018 results were mixed. Class “A” continues to improve, and various signs of improvement were evident in the “A/R”, “B”, and “Non-Traditional” class categories. While overall vacancy remains high across all competitive categories, the rate dropped to 24.3%, down 1.8% since May 2017. Two major corporate downsizings and ongoing consolidations continue to heavily impact the downtown market – Kodak and Xerox. Kodak released Building 15 from the “Non- Competitive” category to Class “B”, and Xerox Tower went entirely vacant the day after our survey period ended. When Xerox Tower’s vacancy is included, the vacancy rate jumps to 32.9% for all downtown competitive space, and to 41.2% for Class “A”. Ironically, without consideration of Xerox’ movement out of downtown to consolidate in Webster, absorption in downtown competitive space actually ran positive between 2017 and 2018 by over 165,000 square feet. -

Central Library of Rochester and Monroe County · Historic

Central Library of Rochester and Monroe County · Historic Scrapbooks Collection Central Library of Rochester and Monroe County · Historic Scrapbooks Collection ^ When Gotham Paid to Rochester*s First Citizen Homage - AM. 3 - . 0 71 fJEOhoctar Public Ufrf-mr* 64 Court Sti PAVL CLAUDEL iliitn THOMAS* J* \s M.n<J WATSONrw n. * u v *< GEORGE B. DRYDEN GEORGEe> EASTMAN>aoi J.J Genesee. The Kodak is shown with ? rapher who snapped this photo used for the first s an corner of the big dining magnate important ., 'j.^. _r ..-_- T-i__.j 73. .li r> _-_.. _r . _ . _* i :-.- -, Rubber of camera a the Commodore Hotel in New York, the president of the Dryden Company time a new type of press employing who is his niece's husband; President night, when world celebrities gathered Chicago, supersensitive panchromatic film which requires Watson of the of the Genesee, and M. tribute to George Eastman, guest of Society no flashlight. France. The International Ntwareel Photo annual dinner of the of the Claudel, embassador from photog- the Society ? .Rhees Tells Diners of Eastman's Modesty Tn*. Rush Rhees, president of the can enjoy the spectacle. That University oi Rochester, who has spectacle is before his eyes, and accepted from Mr. Ka.it man mil all oyes, on every hand in Roch lions of dollars worth of besetac- ester. We have several buildings lions in behalf of Roche-tor insti tutions, paid the following tribute which bear his name. Rut that for thp community to 'ho Kodak seems not to interest him great he is not in- manu lilanthropist at the ly. -

SURVEY of DOWNTOWN OFFICE SPACE, June 2019

SURVEY OF DOWNTOWN OFFICE SPACE June 20 19 dorf ROCHESTER DOWNTOWN DEVELOPMENT CORPORATION 100 Chestnut Street, Suite 1910 ~ Rochester, New York 14604 (585) 546-6920 ~ [email protected] ~ www.rochesterdowntown.com The Rochester Downtown Development Corporation’s SURVEY OF DOWNTOWN OFFICE SPACE, June 2019 Executive Summary RDDC tracks office buildings located in downtown Rochester, defined as the area within the former Inner Loop, and High Falls, Upper East End, and Alex Park. Downtown’s commercial building inventory contains the region’s oldest office structures as well as its newest towers. This year, RDDC is tracking 9.4 million square feet in 114 office buildings. Of these, 85 are competitive buildings, with 6.6 million square feet and representing 70% of all downtown space. KEY FINDINGS Vacancy in is up in all categories except Class “B”. Overall, competitive vacancy is up 7.8%, but Class “A” rose by 18.4% since 2018. Behind these numbers, is the story of three large office buildings: Xerox Tower, and Buildings 10 & 15 at Kodak Office on State Street. Changing Corporate Fortunes Xerox Tower (580,636 SF, Class “A”) was shown as fully occupied as of the June 30th cutoff for our 2018 Survey. But on July 1st, the property became fully vacant as Xerox consolidated all of its downtown operations into its Webster campus. It is important to note the impact of this single, very significant property; when Xerox Tower is removed from the calculations in 2018 and 2019, Class “A” vacancy drops from 25.7% to 22.7%, and competitive space vacancy overall from 26.5% to 25.5%. -

Kodakery; Vol. 6, No. 8; April 8, 1948

A NEWSPAP KODAK COMPANYe April 8, 1948 Suggestion System Is 50 Today Banner Year Indicated Rank Sees By 1st Quarter Report Movie Gain Fifty years old today-the Kodak Suggestion System appears t o be in its lustiest year of growth. Figur es gath ered from the divisions in Rochester on the h alf For British century anniversary show that r--------------~ men and wom en of the Company gan on Apr. 8, 1898, at Kodak P ark, are well on their way to setting the Company has paid $636,962 to His 'Gr eat Expectations' important new records this year. people who have presented work- Won Academy Award In the first quarter of 1948 they able ideas, which reached 71 ,258 have earned $35,078 on their ideas at the close of the third period. J. Arthur Rank, British Cine presented to improve num erous Three all-time r ecords were re mogul, has "great expectations" for operations in m anufacturing and ported at Camera Works in the his m otion pictures both in the third period of 1948. The Sugges Empire and America. And this tion Committee there processed offers a good future for Kodak The $636,962 earned by Ko 539 ideas and 123 of them were Ltd.'s manufacturin g of motion dak people on suggestions since approved with awards totaling picture fi lm, for all Rank m ovies, the system was inaugurated 50 $5159, each of the three figures he said, are m ade on Kodak film. years ago today would make representing a new high. -

The Semaphore

The Semaphore Newsletter of the Rochester NY Chapter, NRHS November 2005 P.O. Box 23326, Rochester, NY 14692-3326; Published Monthly Volume 48, No. 3 Program for Nov. 17: Five locomotives from three manufacturers in one picture! Rochester Transportation by Donovan Shilling Donovan, our Chapter Historian, will enlighten our November meeting attend- ees with just a small segment of Roches- ter transportation over the years. You can expect a lively and enthusiastic presentation. Don has just released his fifth book in the "Images of America" series. He will likely have a few copies available for purchase and gladly autograph purchased copies. Meeting starts at 7:30 Program follows at about 8:15 Store is open before and at Future Programs The R&GV Railroad Museum's Industry yard is a buzz with engines this rainy October Dec. 15: Williamsport in the Late Steam morning as the museum sets up Industry yard for the winter. (Chris Hauf photo) Era by Bill Bigler 2006 Jan. 19: Railroad Stories of Long Ago, by Michael Rickert Feb 16: Mike's Photo Gallery, by Mike Roque' March 16: Member's Slide Night Chapter Library 11 May Street, Webster (by OMID Tracks) Winter Hours in Effect Hours: 2:00 to 5:00 PM Sunday, November 20 Library Phone: 872-4641 Chris Hauf presented R&GV RR lanterns to John Slater, Dave Allen and Bill Quick, all of Great News on Trolley the Nickel Plate History and Technical Society Chapter of Buffalo. They presented a fine Substation - see Page 4. program on the NKP, stressing steam with slides along with photos and 'paper goods'. -

Table of Contents

Table of Contents List of Council Members Message from the Co-Chairs 1. Executive Summary United for Success 2. Progress State of the Region Status of Past Priority Project Progress Priority Project Progress Summary of All Past Priority Projects Leverage of State Investment in All Past Priority Projects Status of All Projects Awarded CFA Funding Aggregated Status of All CFA Projects Leverage of State Investment in All CFA Projects Job Creation Upstate Revitalization Initiative (URI) Update Mapped Status of Past Priority/URI Projects 3. Implementation Agenda Implementation of 2017 State & Regional Priorities Workforce Development Pathways to Prosperity Higher Education, Research, & Healthcare Life Sciences Optics, Photonics, & Imaging Agriculture & Food Production Next Generation Manufacturing & Technology Eastman Business Park Science & Technology Advanced Manufacturing Park (STAMP) Downtown Innovation Zone Entrepreneurship & Development Global NY Tourism & Arts Infrastructure & Transportation Sustainability Proposed Priority Projects Overall Investment Ratio for Proposed Priority Projects Proposed Priority Projects Relating to State Priorities Map of Proposed Priority Projects Additional Priority Projects 4. Participation Community Engagement & Public Support Interregional Collaboration Work Team Descriptions & Membership Lists Downtown Revitalization Initiative List of Council Members Co- Anne Kress President Monroe Community College Chair Co- Bob Duffy President & CEO Greater Rochester Chamber of Commerce Chair Ginny Clark Sr. VP of Public Affairs Constellation Brands, Inc. Matt Cole Vice President Commodity Resource Corp. Paul Fortin Plant Controller Precision Packaging Products Steve Griffin CEO Finger Lakes Economic Development Center / Yates County Industrial Development Agency Matt Hurlbutt President & CEO Greater Rochester Enterprise Steve Hyde President & CEO Genesee County Economic Development Center Tony Jackson President Panther Graphics David Mansfield President & Owner Three Brothers Winery & Estates Theresa Mazzullo CEO Excell Partners, Inc. -

Letters Review University of Rochester Summer 1980

Rochester Letters Review University of Rochester Summer 1980 Kodak Centennial Tribute Features More on Eastman To the editor: The Eastman Touch House Sparrows The well- known Parisian art George Eastman and the University And other poems by Anthony Hecht dealer R ene Gimpel in his Diary ofan of Rochester Page 25 Art D ealer, published in France in Page 2 1963 and in New York in 1966, had The Man Who Made It the following on George Eastman in The Double Life of the entry for February 27, 1919: to First Bass-And Way When I went to Eastmon'sfo r thefi rst Rudolf Kinzslake Beyond time, I asked him wherehe kept The Blue Bridging the gap between industry Double bassist James Van D emark Rockets, one cifthe most magnificent and aca de mia Page 27 Turners in existence. "No one, " he Page 10 answered, "canjudge the beauty ofa pic Glassmaker ture as well as I; I've a method of my own, The Kodak Kids Photo story and neithery ou noranyone elsecan equal Kodak Scholars at Rochester me because no one has as much knowledge Page 30 Page 13 ofphotography. When I lookat a picture, I ask myself: 'Ifthis view, scene, or portrait Mr. Eastman's Departments had been a photograph from real life, would it appearas it do es here?' Ifthe Theatre Rochester in Review 34 answer is negative, it meansthe painting is The Eastman Theatre and how it not right. Now then, afterI bought that got that way Alumnotes 42 In Memoriam 55 Tumei; I saw that certain waves ofthe sea Page 16 could not have appeared in a photographic Travel Corner 56 print as he hadpainted them!" Family Album o shade ofTurn et; didyou shudder when Who says town and gown don't mix? the emperor ofphotography spokethus? Page 19 Susan E. -

Kodak Tower Commons Brochure

Our space. Your business. Complete corporate amenities for users big and small in a desirable downtown location. Reception Area & Theater Additional Amenities Location The lobby reception area and adjoining Kodak Tower Commons has a The High Falls Historical district of 50-seat ‘Little Theater’ create an excellent gymnasium, fitness center, squash Rochester, NY is a great spot for place to receive guests before and after courts, an employee lounge and more. innovation and entertainment. The presentations. Easy access in the main district is named for the 96-foot Genesee lobby of the Kodak Tower building. These great facilities combined River Water Fall, the highest of any major with programs for recreation and city in the United States. Conference Rooms fitness help employees get maximum Executive conference rooms suitable enjoyment and health benefit. Surrounding the falls are office buildings, for board meetings are available for Organized basketball, volleyball, yoga restaurants and residences, a compact use by members of the Kodak Tower and dance classes are all part of the community in an amazing place. Steps Commons along with a range of less experience. And there’s plenty of on- away from Frontier Field, home of formal conference rooms throughout site parking available. baseball’s Red Wings. And in the center the complex. of it all is Kodak Tower Commons, World Headquarters of Eastman Kodak Company, the Downtown Campus of Monroe Community College, Carestream and ESL. Why Kodak Tower Commons? Shared amenities High falls area Planned