Cultural Diversity and the Transformation of Public Space in Melbourne

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Museums and Australia's Greek Textile Heritage

Museums and Australia’s Greek textile heritage: the desirability and ability of State museums to be inclusive of diverse cultures through the reconciliation of public cultural policies with private and community concerns. Ann Coward Bachelor of General Studies (BGenStud) Master of Letters, Visual Arts & Design (MLitt) A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Art History and Theory College of Fine Arts University of New South Wales December, 2006 ORIGINALITY STATEMENT ‘I hereby declare that this submission is my own work and to the best of my knowledge it contains no materials previously published or written by another person, or substantial proportions of material which have been accepted for the award of any other degree or diploma at UNSW or any other educational institution, except where due acknowledgement is made in the thesis. Any contribution made to the research by others, with whom I have worked at UNSW or elsewhere, is explicitly acknowledged in the thesis. I also declare that the intellectual content of this thesis is the product of my own work, except to the extent that assistance from others in the project’s design and conception or in style, presentation and linguistic expression is acknowledged.’ Signed .................................................................. ABSTRACT This thesis explores the desirability of Australia’s State museums to be inclusive of diverse cultures. In keeping with a cultural studies approach, and a commitment to social action, emphasis is placed upon enhancing the ability of State museums to fulfil obligations and expectations imposed upon them as modern collecting institutions in a culturally diverse nation. -

Free Tram Zone

Melbourne’s Free Tram Zone Look for the signage at tram stops to identify the boundaries of the zone. Stop 0 Stop 8 For more information visit ptv.vic.gov.au Peel Street VICTORIA ST Victoria Street & Victoria Street & Peel Street Carlton Gardens Stop 7 Melbourne Star Observation Wheel Queen Victoria The District Queen Victoria Market ST ELIZABETH Melbourne Museum Market & IMAX Cinema t S n o s WILLIAM ST WILLIAM l o DOCKLANDS DR h ic Stop 8 N Melbourne Flagstaff QUEEN ST Gardens Central Station Royal Exhibition Building St Vincent’s LA TROBE ST LA TROBE ST VIC. PDE Hospital SPENCER ST KING ST WILLIAM ST ELIZABETH ST ST SWANSTON RUSSELL ST EXHIBITION ST HARBOUR ESP HARBOUR Flagstaff Melbourne Stop 0 Station Central State Library Station VICTORIA HARBOUR WURUNDJERI WAY of Victoria Nicholson Street & Victoria Parade LONSDALE ST LONSDALE ST Stop 0 Parliament Station Parliament Station VICTORIA HARBOUR PROMENADE Nicholson Street Marvel Stadium Library at the Dock SPRING ST Parliament BOURKE ST BOURKE ST BOURKE ST House YARRA RIVER COLLINS ST Old Treasury Southern Building Cross Station KING ST WILLIAM ST ST MARKET QUEEN ST ELIZABETH ST ST SWANSTON RUSSELL ST EXHIBITION ST COLLINS ST SPENCER ST COLLINS ST COLLINS ST Stop 8 St Paul’s Cathedral Spring Street & Collins Street Fitzroy Gardens Immigration Treasury Museum Gardens WURUNDJERI WAY FLINDERS ST FLINDERS ST Stop 8 Spring Street SEA LIFE Melbourne & Flinders Street Aquarium YARRA RIVER Flinders Street Station Federation Square Stop 24 Stop Stop 3 Stop 6 Don’t touch on or off if Batman Park Flinders Street Federation Russell Street Eureka & Queensbridge Tower Square & Flinders Street you’re just travelling in the SkyDeck Street Arts Centre city’s Free Tram Zone. -

A 'Common-Sense Revolution'? the Transformation of the Melbourne City

A ‘COMMON-SENSE REVOLUTION’? THE TRANSFORMATION OF THE MELBOURNE CITY COUNCIL, 1992−9 A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy April, 2015 Angela G. Munro Faculty of Business, Government and Law Institute for Governance and Policy Analysis University of Canberra ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This thesis is the culmination of almost fifty years’ interest professionally and as a citizen in local government. Like many Australians, I suspect, I had barely noticed it until I lived in England where I realised what unique attributes it offered, despite the different constitutional arrangements of which it was part. The research question of how the disempowerment and de-democratisation of the Melbourne City Council from 1992−9 was possible was a question with which I had wrestled, in practice, as a citizen during those years. My academic interest was piqued by the Mayor of Stockholm to whom I spoke on November 18, 1993, the day on which the Melbourne City Council was sacked. ‘That couldn’t happen here’, he said. I have found the project a herculean labour, since I recognised the need to go back to 1842 to track the institutional genealogy of the City Council’s development in the pre- history period to 1992 rather than a forensic examination of the seven year study period. I have been exceptionally fortunate to have been supervised by John Halligan, Professor of Public Administration at University of Canberra. An international authority in the field, Professor Halligan has published extensively on Australian systems of government including the capital cities and the Melbourne City Council in particular. -

Docklands to Host Australia's Largest Ever Cycling Event

OCTOBER - NOVEMBER ISSUE 22 Priceless CELEBRATING THREE YEARS AS your LOCAL PAPER Docklands to host Australia’s largest ever cycling event Politicians, Olympians, AFL footballers and thousands of other keen cyclists will participate in the annual Portfolio Partners Around The Bay In A Day cycle challenge on Sunday 15 October 2006. This year the event aims to raise over $400,000 towards its official charity partner, The Smith Family. Departing and returning to Docklands, the largest Five hundred teams, including serious cyclists, Serious riders have booked out the 250km and 210km number of cyclists in Australia will get together to celebrities, business leaders and leisurely riders events, but places in the 42km Great Melbourne Bay challenge themselves, their colleagues, friends and have been sponsored by family and friends. All Ride and the Classic 100km course are still available. each other in a single day ride around Port Phillip Bay. proceeds will go to The Smith Family. Entry is open to individuals or to teams that have a Waterfront City Piazza will be the centre of activity minimum of four riders. Melbourne footballer Cameron Bruce and Ben at the conclusion of Australia’s biggest one-day Dixon from Hawthorn will ride together. The Docklands Marketing Association is a challenge bike ride, hosting the Finish Festival with proud sponsor of Around the Bay in a Day and live music, a cycling expo, dining offers and lots more. Premier Steve Bracks, Sports Minister Justin encourages the community to come and cheer on the riders as they return to Docklands. Bicycle Victoria is thrilled with the level of interest Madden, VicHealth CEO Rob Moodie, Bicycle in the event, now in its 14th year, which has broken Victoria president Simon Crone and Jayco Herald For more information on “Around the Bay in records with 13,000 riders already signed up. -

Hellenes in Western Australia: a Century of Changing Relations, Responses and Contribution

Title: Hellenes in Western Australia: A century of changing relations, responses and contribution. Presenter: Dr John Yiannakis Organisation: University of Western Australia Australia was a society that dreaded the “mixing of races” and was obsessed with protecting racial purity. Such sentiments were well expressed by Western Australia’s Premier John Forrest who, in 1897, concluded debate about his state’s Immigration Restriction Bill by saying “we desire to restrict this country, so that it shall not be over-run with races whose sympathies, and manners and customs, are not as ours.”1 Forrest, like other colonial leaders forging the new Commonwealth of Australia, wanted the nation, and his state, to remain British, Protestant and white; a desire enshrined in the legislation that became known as the White Australia Policy. While this policy was aimed primarily at prohibiting the entry of Asians and non-Europeans to Australia, it also made it difficult for non-British Europeans to enter. For early 20th century Australia an “olive peril” was almost as threatening as the yellow one. In the coming years, government policy towards Hellenic (Greek) arrivals would fluctuate. Restrictions and quotas would be imposed, only to be disregarded, and then observed stringently. The fear and contempt held by Anglo-Australians for most Greeks and other southern Europeans intensified as their numbers increased. Verbal and physical abuses were common forms of antagonism. Overseas and Australian born Greeks, pre and post 1945, had to endure a seemingly endless list of derogatory names. Anti-foreign sentiment was prevalent throughout society. Even the local schoolyard could be a place perpetuating bigotry and division. -

Heroes Are Forged, Not Born

Aug. 2019 Sep. 2019 Heroes are forged, not born. During World War II, the famous IL-2 kept flying even after being riddled by anti-aircraft shells and machine-gun fire from other planes. Although badly damaged, it finally made its way back home. Contents August 2019 01. Ren Zhengfei's Interview with Sky News 01 02. Ren Zhengfei's Interview with The Associated Press 43 03. David Wang's Interview with Sky News 76 04. Eric Xu's Media Roundtable at the Ascend 910 and 84 MindSpore Launch 05. Guo Ping's Irish Media Roundtable 107 06. Eric Xu's Interview with Handelsblatt 135 07. Eric Xu's Speech at the Ascend 910 and MindSpore Launch 155 08. David Wang's Speech at the World Artificial Intelligence 164 Conference September 2019 09. Ren Zhengfei's Interview with The New York Times 176 10. Ren Zhengfei's Interview with The Economist 198 11. Ren Zhengfei's Interview with Fortune 227 12. A Coffee with Ren II: Innovation, Rules & Trust 248 13. Eric Xu's Interview with Bilanz 309 14. Catherine Chen's Interview with France 5 331 15. Guo Ping's UK Media Roundtable 355 16. Liang Hua's Meeting with Guests at China-Germany-USA 378 Media Forum 17. Eric Xu's Speech at Swiss Digital Initiative 402 18. William Xu's Speech at Huawei Asia-Pacific Innovation 408 Day 2019 19. Ken Hu's Speech at Huawei Connect 2019 420 20. Ken Hu's Opening Speech at the TECH4ALL Summit 435 Ren Zhengfei's Interview with Sky News Ren Zhengfei's Interview with Sky News August 15, 2019 Shenzhen, China 01 Ren Zhengfei's Interview with Sky News Tom Cheshire, Asia Correspondent, Sky News : Mr. -

7- Chapter 1: Migration of Greeks to Australia: an Historical Overview

-7- CHAPTER 1: MIGRATION OF GREEKS TO AUSTRALIA: AN HISTORICAL OVERVIEW Poised on the edge of two worlds, the migrant continues to search for a sense of belonging Liz Thompson. The thrust of the thesis will be the study of the life of Greek migrants who came to Australia with professional qualifications. Being migrants themselves, they were subjected to the same sociopolitical and cultural situations which pre y filed in Australia at the time of their migration, in a way similar to the majority of ordinary migrants. The expectations of professional migrants in AL stralia were different to those of non-professional Greek migrants and although they were both foreigners in a foreign environment, each of the two groups reacted differently to the social pressures, as will be seen from the information collected in the interviews and published literature. With the exception of some statistical data and information on qualifications published by the Government', there is hardly any other documented information available on professional Greek migrants in Australia. As a consequence, this chapter will attempt to provide an overview of those areas which correspond to the situations faced by Greek professional migrants in Australia. Australia has historically been a nation of migrants who., as a whole, speak more than 100 languages and dialects with people coming from many countries of the world. The Australian culture which originally developed on the attitudes of the then British dominated population, was far different from the cultural diversity of the Australian society as it has developed since the Second World War'. These changes have been the result of a huge migration program and the role played by the multicultural policies of successive Australian governments, which have modified social attitudes during the past two decades. -

Report to the Future Melbourne (Planning) Committee Agenda Item 6.2

Page 1 of 49 Report to the Future Melbourne (Planning) Committee Agenda item 6.2 Ministerial Planning Referral: TPM-2013-31 6 May 2014 19-25 Russell Street and 150-162 Flinders Street, Melbourne Presenter: Angela Meinke, Manager Planning and Building Purpose and background 1. The purpose of this report is to advise the Future Melbourne Committee of a Ministerial Planning Application (reference 2013/009973) at 19-25 Russell Street and 150-162 Flinders Street, Melbourne. Notice of the planning application was given by the Department of Transport, Planning and Local Infrastructure (DTPLI) on 20 December 2013 (refer Attachment 2 – Locality plan and Attachment 3 – Proposed plans). 2. The applicant is Clement Stone Town Planners, the owner is Forum Theatre Holdings Pty Ltd and the architect is Bates Smart Pty Ltd. 3. The subject site is located within the Capital City Zone 1; Design and Development Overlays Schedule 1 –A2 (active street frontage), 2 A5 (40 metre discretionary height control), 4 (weather protection); Heritage Overlay Schedules 505 (Flinders Gate Precinct) and 653 (Forum Theatre) and Parking Overlay 1. 4. The application proposes the demolition of the MTC building at 25 Russell Street and the construction of a 32 level (107 metre) tower for a residential hotel, ground level retail, commercial and residential uses (refer Attachment 3 – Proposed plans). The application also proposes refurbishment of the Forum Theatre. 5. The Forum Theatre is on the Victorian Heritage Register (HO438) and an application has been lodged with Heritage Victoria for the refurbishment works and for a 3.5 metre projection of the tower over the rear of the Forum. -

Advocate for Energy Management • Provide Assistance on Policies and Programs • Develop Tools and Resources

4th U.S.-China Energy Efficiency Forum September 25, 2013 Compiled Presentations from Track 2, Breakout Session 2/Afternoon Energy Management in Energy- Intensive Facilities The Green Grid: Accelerating the Resource Efficient Digital Economy John Tuccillo The Green Grid President and Chairman of The Board Schneider Electric, Senior Vice President , Industry and Government The global authority on resource efficient information technology and data centers. Over 200 Members Worldwide More than 4,000 active participants Connected Global Interest Groups • Data Center Maturity Model 2.0 Harqs Singh of Thomson Reuters • Data Center and ICT Utilization: Mark Aggar of Microsoft • Software Efficiencies: Kim Shearer of Microsoft • Water: Winnie Lam of Google • TGG Data Center Logo Program: Jack Pouchet of Emerson • Government Engagements: Rona Newmark of EMC • Cloud Efficiencies: Winston Saunders of Intel • Data Center Life Cycle: Christophe Garnier of Schneider Electric Copyright © 2013, The Green Grid More than 400 Deliverables Hundreds of Thousands of Downloads White Papers Webcasts Detailed Reports Case Studies On-line Tools Copyright © 2013, The Green Grid Copyright © 2013, The Green Grid New Tools Data Center Maturity Model Assessment Tool Over 400 active assessments! • Outlines current best practices and a 5 year industry roadmap • Purpose: . Evaluate your data center and IT portfolio . Access your personal DCMM equalizer . Obtain benchmarking results Updated Air-Side Free Cooling Maps • ASHRAE Class A2 and A3 Maps for: . EMEA . Japan . North America Copyright © 2013, The Green Grid Copyright © 2013, The Green Grid Green Grid China 2013 The Green Grid China Forum 2013 Agenda Time Topic Speaker 08:30-09:00 Registration 09:00-09:10 Opening Speech David Wang, Ph.D. -

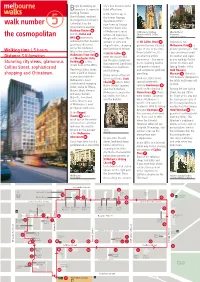

Walk Number the Cosmopolitan

egin by walking up city’s fine theatresat the BSwanston St, opposite ticket office here. bustling Flinders A little further up, is Street Station, and past the former Georges the magnificent St Paul’s department store – walk number 5 Cathedral. Pass the now home to George monument to explorer Patterson Bates (one Matthew Flinders 1 of Melbourne’s most St Michaels Uniting Westin Hotel and the Burke and famous ad agencies). Church and 101 Collins forecourt, the cosmopolitan Street Swanston Street Wills 2 monument Mingle with smart office dedicated to their doomed workers in suits and of 101 Collins Street 10 , Opposite is the journey of discovery elegant ladies, shopping go into the neo-classical Melbourne Club 15 , a across the continent. and lunching at leisure. foyer. Home to the city’s private gentleman’s club Walking time 1.5 hours Take in the view of the At 161 On Collins 7 , financial whizzes, it’s - you can almost smell Melbourne Town Hall 3 an amazing artistic the leather and cigars Distance 3 Kilometres and Manchester Unity enter the atrium and see the glass sculptures experience – four water as you walk by. On the Stunning city views, glamorous Building 4 , a deco pools, stunning marble corner of Collins and dream built in the 1930s. that represent Significant Collins Street, sophisticated Melbourne Landmarks and granite columns Spring Streets, is the Reaching Collins Street, and Buildings. and sumptuous gold leaf Gold Treasury shopping and Chinatown. catch a whiff of Chanel panelling. Museum 16 , Victoria’s as you turn right into At the corner of Russell Back on Collins Street, ‘Old Treasury’ designed in Melbourne’s most Street you’ll pass Scots several nineteenth the 1850s by 19-year-old sophisticated shopping Church 8 , where Dame century townhouses 11 J.J.Clark. -

Department of Infrastructure Annual Report 1997-1998

DEPARTMENT OF INFRASTRUCTURE ANNUAL REPORT 1997–98 Contents Secretary’s foreword iii About the department of infrastructure 1 Organisational structure 2 Land-use and transport planning 3 CONTENTS Making a difference 3 Strategic framework 4 A new metropolitan strategic framework 5 Rural and regional policy 5 Major projects coordination 7 Major civic projects – agenda 21 7 Building services 11 Melbourne city link and exhibition street extension 14 DEPARTMENT OF INFRASTRUCTURE DEPARTMENT Melbourne docklands and multipurpose stadium 15 Federation square and jolimont project coordination 17 Sports and entertainment precinct and relocation of the batman avenue tram 17 Airport link 18 Southbank development 18 Road system management 19 Road development 19 Road system maintenance 20 Traffic and road use management 21 Public transport 23 Corporatisation of the public transport corporation and franchising the businesses 23 Bus contracts 24 Metropolitan bus services 25 Improved public transport performance 27 V/Line Freight and Victrack 29 National transport agenda 30 Transport safety and regulation 31 Public transport safety and regulation 31 Road safety 33 Registration and licensing 34 Taxi and tow-truck initiatives 34 Planning, local government and heritage 35 Local government 35 Statutory planning 39 Heritage 42 Land monitoring 43 Building policy 43 Panels 43 International affiliations 44 Creating a value-adding organisation 45 Regionalisation 45 Business systems 46 Information technology 48 Implementing output management 49 Human resource strategies -

Melbourne City Map BERKELEY ST GARDENS KING WILLIAM ST Via BARRY ST

IAN POTTER MUSEUM OF ART STORY ST Accessible toilet Places of interest Bike path offroad/onroad GRAINGER ELGIN ST MUSEUM To BBQ Places of worship City Circle Tram route Melb. General JOHNSON ST CINEMA BRUNSWICK ST Cemetary NOVA YOUNG ST with stops NAPIER ST MACARTHUR SQUARE GEORGE ST Cinema Playground GORE ST VICTORIA ST SMITH ST Melbourne Visitor UNIVERSITY KATHLEEN ROYAL SYME FARADAY ST WOMEN’S ROYAL OF MELBOURNE CENTRE Community centre Police Shuttle bus stop HOSPITAL MELBOURNE 6 HOSPITAL ROYAL FLEMINGTON RD DENTAL Educational facility Post Office Train station HOSPITAL HARCOURT ST GRATTAN ST MUSEO ITALIANO CULTURAL CENTRE BELL ST GREEVES ST Free wifi Taxi rank Train route 7 LA MAMA THEATRE CARDIGAN ST LYGON ST BARKLY ST VILLIERS ST ROYAL PDE Hospital Theatre ARDEN ST ST DAVID ST Tram route with CARLTON ST platform stops GRATTAN ST Major Bike Share stations Toilet MOOR ST Tram stop zone WRECKYN ST SQUARE MOOR ST BAILLIE ST ARTS HOUSE, To Sydney CARLTON Marina Visitor information MEAT MARKET UNIVERSITY STANLEY ST Melbourne city map BERKELEY ST GARDENS KING WILLIAM ST via BARRY ST centre LEICESTER ST DRYBURGH ST PELHAM ST BLACKWOOD ST Sydney Rd PROVOST ST CONDELL ST Parking COURTNEY ST Accessible toilet Places of interest BikeThis path mapABBOTSFORD ST offroad/onroadis not to scale ELIZABETH ST QUEENSBERRY ST PIAZZA HANOVER ST LINCOLN PELHAM ST ITALIA BEDFORD ST CHARLES ST BBQ Places of worship 0 City Circlemetres Tram route360 BERKELEY ST SQUARE ARGYLE PELHAM ST To Eastern BARRY ST SQUARE Fwy, Yarra with stops IMAX Ranges via ARTS HOUSE,