University of Oklahoma Graduate College Shakespeare, Authority, and the English Catholic Experience a Dissertation Submitted To

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

In Conversation with Christos Yannaras: a Critical View of the Council of Crete

In conversation with Christos Yannaras: a Critical View of the Council of Crete Andreas Andreopoulos Much has been said and written in the last few months about the Council in Crete, both praise and criticism. We heard much about issues of authority and conciliarity that plagued the council even before it started. We heard much about the history of councils, about precedents, practices and methodologies rooted in the tradition of the Orthodox Church. We also heard much about the struggle for unity, both in terms what every council hopes to achieve, as well as in following the Gospel commandment for unity. Finally, there are several ongoing discussions about the canonical validity of the council. Most of these discussions revolve around matters of authority. I have to say that while such approaches may be useful in a certain way, inasmuch they reveal the way pastoral and theological needs were considered in a conciliar context in the past, if they become the main object of the reflection after the council, they are not helping us evaluate it properly. The main question, I believe, is not whether this council was conducted in a way that satisfies the minimum of the formal requirements that would allow us to consider it valid, but whether we can move beyond, well beyond this administrative approach, and consider the council within the wider context of the spiritual, pastoral and practical problems of the Orthodox Church today.1 Many of my observations were based on Bishop Maxim Vasiljevic’s Diary of the Council, 2 which says something not only about the official side of the council, but also about the feeling behind the scenes, even if there is a sustained effort to express this feeling in a subtle way. -

A Letter to Pope Francis Concerning His Past, the Abysmal State of Papism, and a Plea to Return to Holy Orthodoxy

A Letter to Pope Francis Concerning His Past, the Abysmal State of Papism, and a Plea to Return to Holy Orthodoxy The lengthy letter that follows was written by His Eminence, the Metropolitan of Piraeus, Seraphim, and His Eminence, the Metropolitan of Dryinoupolis, Andrew, both of the Church of Greece. It was sent to Pope Francis on April 10, 2014. The Orthodox Christian Information Center (OrthodoxInfo.com) assisted in editing the English translation. It was posted on OrthodoxInfo.com on Great and Holy Monday, April 14, 2014. The above title was added for the English version and did not appear in the Greek text. Metropolitan Seraphim is well known and loved in Greece for his defense of Orthodoxy, his strong stance against ecumenism, and for the philanthropic work carried out in his Metropolis (http://www.imp.gr/). His Metropolis is also well known for Greece’s first and best ecclesiastical radio station: http://www.pe912fm.com/. This radio station is one of the most important tools for Orthodox outreach in Greece. Metropolitan Seraphim was born in 1956 in Athens. He studied law and theology, receiving his master’s degree and his license to practice law. In 1980 he was tonsured a monk and ordained to the holy diaconate and the priesthood by His Beatitude Seraphim of blessed memory, Archbishop of Athens and All Greece. He served as the rector of various churches and as the head ecclesiastical judge for the Archdiocese of Athens (1983) and as the Secretary of the Synodal Court of the Church of Greece (1985-2000). In December of 2000 the Holy Synod of the Ecumenical Patriarch elected him as an auxiliary bishop of the Holy Archdiocese of Australia in which he served until 2002. -

The Equipping Church: Recapturing God’S Vision for the Priesthood of All Believers

THE EQUIPPING CHURCH: RECAPTURING GOD’S VISION FOR THE PRIESTHOOD OF ALL BELIEVERS. A BIBLICAL, HISTORICAL, AND REFORMED PERSPECTIVE. A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE SCHOOL OF THEOLOGY FULLER THEOLOGICAL SEMINARY IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE DOCTOR OF MINISTRY BY JUSTIN CARRUTHERS AUGUST 2019 Copyright© 2019 by Justin Carruthers All Rights Reserved ABSTRACT The Equipping Church: Recapturing God’s Vision for the Priesthood of All Believers. A Biblical, Historical, and Reformed Perspective Justin Carruthers Doctor of Ministry School of Theology, Fuller Theological Seminary 2019 Many protestant versions of believers’ royal priesthood, including the Christian Reformed Church in North America, are missionally inadequate: priestly functions are often monopolized by the Ministerial Priesthood,1 which leads to the defrocking of the ministry of the priesthood of all believers. In essence, the doctrine of the priesthood of all believers is treated as though it is a true, factual, and fascinating piece of Christian doctrine, but is not always practically lived out in local congregations. We believe in it in theory, but not in practice. A biblical and missional understanding of the church must root the priesthood of all believers in baptism, the initiatory rite that ordains all people into priestly service in the world. A proper re-framing of the priesthood of all believers will serve as the catalyst for a more robust ecclesiology and will be the impetus for the royal priesthood to commit to their earthly vocation to be witnesses of Christ in the world. Content Reader: Dr. David Rylaarsdam Words: 185 1 In the case of the CRCNA, there are four offices of the Ministerial Priesthood: Minister of the Word, Elder, Deacon, and Commissioned Pastor. -

A Review O F the Literature

CHILD SEXUAL ABUSE : A Review o f the Literature The John Jay College Research Team KAREN J . TERRY, Ph .D . Principal Investigator JENNIFER TALLON Primary Researcher PART I - LITERATURE REVIEW his literature review provides the reader with an overview of major academic works concerning child sexual abuse in the general population . This is a comprehensive review of the available literature, though it is not a meta-analysis (a synthesis of research results using various statistical methods to Tretrieve, select, and combine results from previous studies) . During the course of the past thirty years, the field of sex offender research has expanded and become increasingly inter-disciplinary . It would be nearly impossible to review every piece of information relating to the topic of child sexual abuse . Instead, this is a compilation of information pertaining to theories, typologies and treatments that have attained general acceptance within the scientific community. I In reviewing the literature concerning sexual abuse within the Catholic Church, the amount of empirical research was limited, and many of the studies suffered from methodological flaws . Additionally, much of the literature consisted of either anecdotal information or impassioned arguments employed by various researchers when characterizing the responses of the church to this incendiary issue . In providing the reader with a comprehensive review, it was necessary to summarize every point of view no matter how controver- sial. Any of the ideas expressed in this review should not be considered indicative of the point of view of either the researchers at John Jay College of Criminal justice, or the Catholic Church . One aim of this literature review is to put into perspective the problem of child sexual abuse in the Catholic Church as compared to its occurrence in other institutions and organizations . -

Darvish Continues to Struggle

FFORMULAORMULA OONENE | Page 3 MLB | Page 5 Hamilton Los Angeles takes lead from Dodgers Vettel with lose twin Monza win bill to Padres Monday, September 4, 2017 CRICKET Dhul-Hijja 13, 1438 AH Another Kohli GULF TIMES ton as India sweep ODI series 5-0 SPORT Page 4 RALLYING TENNIS Al-Attiyah on verge Nadal battles on, moves a of world title with step closer to Poland Baja win Federer clash The Qatari finished 3min 54sec in front of series rival Jakub Przygonski and now takes an 81-point lead to the remaining two rounds of the series Rafael Nadal of Spain celebrates beating Leonardo Mayer of Argentina (not pictured) on day six of the US Open tennis tournament at USTA Billie Jean King National Tennis Center. PICTURE: Geoff Burke-USA TODAY Sports AFP Shapovalov’s US Open New York dream goes ‘Busta’ New York: Canada’s Denis Shapo- orld number one Rafael valov failed in his bid to become Nadal battled back from the youngest US Open quarter- a set down to reach the finalist for 29 years when he was US Open last 16 for a knocked out by Spanish 12th seed Wninth time Saturday, edging closer to Pablo Carreno Busta in the third a potential semi-fi nal duel with old round yesterday. rival Roger Federer. Qualifier Shapovalov, 18, was beaten Nadal, 31, saw off Argentine lucky 7-6, (7/2), 7-6 (7/4), 7-6 (7/3) by loser Leonardo Mayer 6-7 (3/7), 6-3, 26-year-old Carreno Busta, who also 6-1, 6-4, taking his record over the made the French Open quarter- world number 59 from Buenos Aires finals this year. -

Afghan Cricket Hero Rashid Khan Calls for Peace

MONDAY-MAY 24, 2021 Sport 05 Afghan cricket hero Rashid Afghanistan, Tajikistan Khan calls for peace Paralympic committees sign KABUL: Afghanistan’s crick- are being killed in Palestine & Af- MoU on bilateral cooperation et star and national team player ghanistan. Yes, we need to stand KABUL: A Memorandum of camps, as well as joint training istan Paralympic and extended the Rashid Khan has called on world for what is right,” he tweeted. Understanding (MoU) was signed sessions for athletes with disabil- message of the Afghanistan’s Para- leaders to bring peace to the re- His message of peace comes between Afghanistan and Tajiki- ities between the countries. lympic committee to Tajikistan gion. amid the foreign troops withdraw- stan’s Paralympic Committees At the end, Osmani expressed Paralympic head. Rashid Khan said in a tweet al and a sharp increase in fighting here the other day. his gratitude on behalf of Afghan- The Kabul Times on Saturday that having grown up around the country. The MoU which was signed in war he can understand the pain In the past few weeks violent by Nangyali Osmani, press advis- and fear today’s children in Af- clashes have been reported across er of Afghanistan's Paralympic ghanistan suffer. the country with both sides sus- Committee with head of Tajiki- “I’m not (a) politician but call taining heavy casualties. stan Paralympic Committee, on all world leaders to bring peace In addition, so far this year at aimed at exchanging of experienc- to the region. I grew up in war & least 100,000 Afghans have fled es, growth and expansion of Para- understand the fear kids go their homes due to conflict. -

Richard Hooker, “That Saint-Like Man”, En Zijn Strijd Op Twee Fronten

Richard Hooker, “that saint-like man”, en zijn strijd op twee fronten Dr. Chris de Jong Renaissance, Humanisme en de Reformatie hebben in Europa een intellectuele, politieke en godsdienstige aardverschuiving veroorzaakt, die geen enkel aspect van de samenleving onberoerd liet. Toen na ongeveer anderhalve eeuw het stof was neergeslagen (1648 Vrede van Westfalen, 1660 Restauratie in Engeland), was Europa onherkenbaar veranderd. Het Protestantse noorden had zich ontworsteld aan de heerschappij van het Rooms-Katholieke zuiden. Dit raakte de meest uiteenlopende zaken: landsgrenzen waren opnieuw getrokken, dynastieke verhoudingen waren gewijzigd, politieke invloedssferen gefragmenteerd als nooit tevoren en het zwaartepunt van de Europese economie was definitief verschoven van de noordelijke oevers van de Middellandse Zee naar Duitsland en de Noordzeekusten. De door Maarten Luther in 1517 in gang gezette Reformatie heeft de eenheid van godsdienst, cultuur, taal en filosofie grotendeels doen verdwijnen. Dat niet alleen, de verbrokkeling en uitholling van het eens zo machtige Rooms-Katholieke geestelijke imperium, die al in de Middeleeuwen begonnen waren, hebben mede de omstandigheden geschapen waardoor vanaf het midden van de zeventiende eeuw een nieuwe intellectuele beweging Europa kon overspoelen: de Verlichting. In Engeland werd de omwenteling in 1534 (Act of Supremacy) in gang gezet door Koning Hendrik VIII (*1491; r. 1509-1547), een conservatief in godsdienstige zaken die niets van Luther moest hebben. Bijgestaan door de onvermoeibare “patron of preaching” Thomas Cromwell (1485-1540) zegde hij in deze 16de eeuwse Brexit de gehoorzaamheid aan Rome op en maakte zo de weg vrij voor een wereldwijde economische en politieke expansie van Engeland. Ook met de vorming van een zelfstandige Engelse nationale kerk koos Hendrik zijn eigen koers, welk beleid na zijn dood na een korte onderbreking werd voortgezet door zijn dochter, Koningin Elizabeth I (*1533; r. -

Walkden Dodge the Rain to Strengthen Their Grip

44 Tuesday, September 2, 2008 theboltonnews.co.uk Bolton Association PWLNR TBPAPPts Daisy Hill . .24 17 43023238 Atherton . .24 14 541105220 Little Hulton .24 15 630102219 Walshaw . .24 14 37061217 Walkden dodge the rain Darcy Lever .24 14 730167217 Edgworth . .24 12 840114183 Spring View .24 11 85085176 Blackrod . .24 9114095147 Golborne . .24 71331146130 Elton . .24 51360269124 A&T . .24 71250138123 Flixton . .24 51450198112 Standish . .24 5154010596 to strengthen their grip Adlington . .24 2175014262 SATURDAY FLIXTON vELTON Bolton League Elton won by 6wkts Flixton by Gordon Sharrock GChambers bDonnelly . .7 NMoors bDonnelly . .10 WALKDEN’S relentless NBlair bHolt . .8 ZManjra c&b Holt . .16 march towards the title RClews lbw bFitton . .26 continued unabated on Sun- FAafreedi cHall bDonnelly . .27 KWellings cFitton bLomax . .8 day, when they beat the DWilliams not out . .29 weather to score a widely- ANaseer cLomax bDonnelly . .0 SKelly bHolt . .2 predicted victory away to MHughes bDonnelly . .1 basement club Heaton. Extras . .5 Total . .139 They are still not mathemati- Bowling: Donnelly 15-4-34-5; Holt 18-4- cally certain but, after beating 50-3; Fitton 9-2-33-1; Lomax 3-0-21-1. long-time leaders Egerton in Elton PLomax bNaseer . .45 Saturday’s pivotal fixture, Mike MHall cWilliams bNaseer . .22 Bennison’s side reinforced AAli c&b Wellings . .12 their championship credentials DMurray st Williams bNaseer . .13 AStansfield run out . .10 with an emphatic 10-wicket win DFitton not out . .11 Having restricted Heaton to JHamnett not out . .14 128-9 they knew they had to get Extras . .13 a move on if they were going to Total (for 4) . -

News Corporation 1 News Corporation

News Corporation 1 News Corporation News Corporation Type Public [1] [2] [3] [4] Traded as ASX: NWS ASX: NWSLV NASDAQ: NWS NASDAQ: NWSA Industry Media conglomerate [5] [6] Founded Adelaide, Australia (1979) Founder(s) Rupert Murdoch Headquarters 1211 Avenue of the Americas New York City, New York 10036 U.S Area served Worldwide Key people Rupert Murdoch (Chairman & CEO) Chase Carey (President & COO) Products Films, Television, Cable Programming, Satellite Television, Magazines, Newspapers, Books, Sporting Events, Websites [7] Revenue US$ 32.778 billion (2010) [7] Operating income US$ 3.703 billion (2010) [7] Net income US$ 2.539 billion (2010) [7] Total assets US$ 54.384 billion (2010) [7] Total equity US$ 25.113 billion (2010) [8] Employees 51,000 (2010) Subsidiaries List of acquisitions [9] Website www.newscorp.com News Corporation 2 News Corporation (NASDAQ: NWS [3], NASDAQ: NWSA [4], ASX: NWS [1], ASX: NWSLV [2]), often abbreviated to News Corp., is the world's third-largest media conglomerate (behind The Walt Disney Company and Time Warner) as of 2008, and the world's third largest in entertainment as of 2009.[10] [11] [12] [13] The company's Chairman & Chief Executive Officer is Rupert Murdoch. News Corporation is a publicly traded company listed on the NASDAQ, with secondary listings on the Australian Securities Exchange. Formerly incorporated in South Australia, the company was re-incorporated under Delaware General Corporation Law after a majority of shareholders approved the move on November 12, 2004. At present, News Corporation is headquartered at 1211 Avenue of the Americas (Sixth Ave.), in New York City, in the newer 1960s-1970s corridor of the Rockefeller Center complex. -

Notice to the Mayor and Ward Councillors

NOTICE TO THE MAYOR AND COUNCILLORS. An ordinary meeting of the Council of the City of Prospect will be held in the Civic Centre, 128 Prospect Road, Prospect on Tuesday 22 March 2016 at 7.00pm. A G E N D A Members of the public are advised that meetings of Council are video recorded and the recordings of the open session of the meeting will be made available on Council’s website for a period of 2 months 1. OPENING 1.1 Acknowledgment of the Kaurna people as the traditional custodians of the land 1.2 Council Pledge 1.3 Declaration by Members of Conflict of Interest 2. ON LEAVE – Cr A Harris 3. APOLOGIES – 4. CONFIRMATION OF MINUTES OF THE ORDINARY MEETING OF COUNCIL HELD ON TUESDAY 23 FEBRUARY 2016 5. MAYOR’S REPORT (Page 1-2) 6. VERBAL REPORTS FROM COUNCIL REPRESENTATIVES ON LOCAL GOVERNMENT OR COMMUNITY ORGANISATIONS 7. PETITIONS – Nil 8. DEPUTATIONS - Nil 9. MOTIONS ON NOTICE Nil. 10. QUESTIONS WITH NOTICE Nil. 11. QUESTIONS WITHOUT NOTICE 12. PROTOCOL The Council has adopted the protocol that only those items on Committee reports reserved by members will be debated and the recommendations of all items will be adopted without further discussion. 13. REPORT OF COMMITTEES Nil. 14. COUNCIL REPORTS – INFORMATION REPORT Nil. 15. COUNCIL REPORTS Core Strategy 1 – Our Community 15.1 2016 Tourrific Prospect Event Evaluation (Pages 3-104, Recommendation on Page 5) 16. COUNCIL REPORTS Core Strategy 2 – Our Economy 16.1 Intelligent Community Forum Foundation (ICFF) – Board Membership (Pages 105-112, Recommendation on Page 105) 17. -

Business Source Corporate Plus

Business Source Corporate Plus Other Sources 1 May 2015 (Book / Monograph, Case Study, Conference Papers Collection, Conference Proceedings Collection, Country Report, Financial Report, Government Document, Grey Literature, Industry Report, Law, Market Research Report, Newspaper, Newspaper Column, Newswire, Pamphlet, Report, SWOT Analysis, TV & Radio News Transcript, Working Paper, etc.) Newswires from Associated Press (AP) are also available via Business Source Corporate Plus. All AP newswires are updated several times each day with each story available for accessing for 30 days. *Titles with 'Coming Soon' in the Availability column indicate that this publication was recently added to the database and therefore few or no articles are currently available. If the ‡ symbol is present, it indicates that 10% or more of the articles from this publication may not contain full text because the publisher is not the rights holder. Please Note: Publications included on this database are subject to change without notice due to contractual agreements with publishers. Coverage dates shown are the intended dates only and may not yet match those on the product. All coverage is cumulative. Due to third party ownership of full text, EBSCO Information Services is dependent on publisher publication schedules (and in some cases embargo periods) in order to produce full text on its products. Source Type ISSN / ISBN Publication Name Publisher Indexing and Indexing and Full Text Start Full Text Stop Availability* Abstracting Start Abstracting Stop Newspaper -

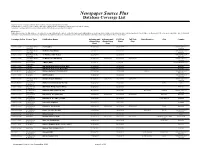

Newspaper Source Plus Database Coverage List

Newspaper Source Plus Database Coverage List "Cover-to-Cover" coverage refers to sources where content is provided in its entirety "All Staff Articles" refers to sources where only articles written by the newspaper’s staff are provided in their entirety "Selective" coverage refers to sources where certain staff articles are selected for inclusion Please Note: Publications included on this database are subject to change without notice due to contractual agreements with publishers. Coverage dates shown are the intended dates only and may not yet match those on the product. All coverage is cumulative. Due to third party ownership of full text, EBSCO Information Services is dependent on publisher publication schedules (and in some cases embargo periods) in order to produce full text on its products. Coverage Policy Source Type Publication Name Indexing and Indexing and Full Text Full Text State/Province City Country Abstracting Abstracting Start Stop Start Stop Cover-to-Cover TV & Radio News 20/20 (ABC) 01/01/2006 01/01/2006 United States of Transcript America Cover-to-Cover TV & Radio News 48 Hours (CBS News) 12/01/2000 12/01/2000 United States of Transcript America Cover-to-Cover TV & Radio News 60 Minutes (CBS News) 11/26/2000 11/26/2000 United States of Transcript America Cover-to-Cover TV & Radio News 60 Minutes II (CBS News) 11/28/2000 06/29/2005 11/28/2000 06/29/2005 United States of Transcript America Cover-to-Cover International 7 Days (UAE) 11/15/2010 11/15/2010 United Arab Emirates Newspaper Cover-to-Cover Newswire AAP Australian National News Wire 09/13/2003 09/13/2003 Australia Cover-to-Cover Newswire AAP Australian Sports News Wire 10/25/2000 10/25/2000 Australia All Staff Articles U.S.