Coalition Politics, Underlying Ideas, and Emerging Discourses

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Case Study of Quota Laws and Women's

TORTOISE AND THE HARE: A CASE STUDY OF QUOTA LAWS AND WOMEN’S REPRESENTATION IN CONGRESS IN ARGENTINA AND THE UNITED STATES © 2016 By Hannah M. Arrington A thesis presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for completion Of the Bachelor of the Arts degree in International Studies at the Croft Institute of International Studies Sally McDonnell Barksdale Honors College The University of Mississippi University, Mississippi December 2016 Approved: _________________________________________ Advisor: Dr. Miguel Centellas _________________________________________ Reader: Dr. William Schenck _________________________________________ Reader: Dr. Carrie Smith Abstract Given recent political tension between political parties in both the United States and Argentina, there has been an increased demand for improved and more accurate congressional representation, specifically women’s substantive representation in Congress. As the first nation to institute a legislative candidate gender quota law, Argentina has been the leading Latin American nation to confront anti-feminist politics. Under the cupo de ley femenino, the quota mandate of 1991, all major political parties and certain governments cabinets in Argentina are required to fill a set thirty percent of positions on party candidate lists with women (Ley No 24.012). Whereas in the United States, there is no requirement for representation by gender, and as of 2016 women occupied twenty percent of each congressional house. Researchers have presented new and debated theories regarding the quality of congresswomen’s representation in various government systems following the introduction of quota laws around the world. Although Argentine female politicians fill a third of seats in both lower and upper congressional houses, they are often perceived as political pawns to male party leaders who seek total obedience from women whom they would not have otherwise elected (Zetterberg). -

The Evolution of Feminist and Institutional Activism Against Sexual Violence

Bethany Gen In the Shadow of the Carceral State: The Evolution of Feminist and Institutional Activism Against Sexual Violence Bethany Gen Honors Thesis in Politics Advisor: David Forrest Readers: Kristina Mani and Cortney Smith Oberlin College Spring 2021 Gen 2 “It is not possible to accurately assess the risks of engaging with the state on a specific issue like violence against women without fully appreciating the larger processes that created this particular state and the particular social movements swirling around it. In short, the state and social movements need to be institutionally and historically demystified. Failure to do so means that feminists and others will misjudge what the costs of engaging with the state are for women in particular, and for society more broadly, in the shadow of the carceral state.” Marie Gottschalk, The Prison and the Gallows: The Politics of Mass Incarceration in America, p. 164 ~ Acknowledgements A huge thank you to my advisor, David Forrest, whose interest, support, and feedback was invaluable. Thank you to my readers, Kristina Mani and Cortney Smith, for their time and commitment. Thank you to Xander Kott for countless weekly meetings, as well as to the other members of the Politics Honors seminar, Hannah Scholl, Gideon Leek, Cameron Avery, Marah Ajilat, for your thoughtful feedback and camaraderie. Thank you to Michael Parkin for leading the seminar and providing helpful feedback and practical advice. Thank you to my roommates, Sarah Edwards, Zoe Guiney, and Lucy Fredell, for being the best people to be quarantined with amidst a global pandemic. Thank you to Leo Ross for providing the initial inspiration and encouragement for me to begin this journey, almost two years ago. -

Fundamentalisms, the Crisis of Democracy and the Threat to Human Rights in South America: Trends and Challenges for Action

Fundamentalisms, the crisis of democracy and the threat to human rights in South America: trends and challenges for action MAGALI DO NASCIMENTO CUNHA FESUR This product is the result of the action of the South American ACT Ecumenical Forum (FESUR) Publishing company: KOINONIA Presença Ecumênica e Serviço Author: Magali do Nascimento Cunha License: Licença CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0 Photos: pixabay.com Translation: Espanhol: Carlos José Beltrán Acero Inglês: Samyra Lawall Graphic design and diagramming: Editora Siano Copyright of this edition by: KOINONIA Presença Ecumênica e Serviço Funded by Act Church of Sweden The views expressed in this document are the sole responsibility of the author and do not necessarily represent the positions of Act Church of Sweden. Support: Index Introduction 5 Argentina 2018 6 Brazil 2016 8 Colombia 2016 10 Peru 2016 12 Elements in common 14 The FESUR research 15 1. Fundamentalisms as a religious-political phenomenon in Latin America 16 1.1 A fertile ground for the emergence of fundamentalism 16 1.2 The search for a definition 20 1.2.1 The many transformations of a concept 21 Protestant origin 21 Internationalization and politicization 22 The Moral Majority, the New Christian Right-wing 23 The contemporary currents of fundamentalism in the United States 23 The Roman Catholic fundamentalist bias 24 1.2.2 An attempt at definition 25 2. Fundamentalist trends in the region 27 2.1 Contextualized fundamentalisms 27 2.1.1 The reaction on sexual and reproductive rights 28 2.1.2 The “pro-family” discourse as an economic-political project 29 2.1.3 Moral panic and permanent clash with enemies 31 2.1.4 Threat to traditional communities 32 2.1.5 Coordinated actions 36 2.1.6 The issues of the Secular State and religious freedom 37 2.2 New US fundamentalist movements in South America 38 2.2.1 Dominion Theology 39 2.2.2 Cultural Warfare 40 2.2.3 Mission among indigenous people 42 3. -

If Not Us, Who?

Dario Azzellini (Editor) If Not Us, Who? Workers worldwide against authoritarianism, fascism and dictatorship VSA: Dario Azzellini (ed.) If Not Us, Who? Global workers against authoritarianism, fascism, and dictatorships The Editor Dario Azzellini is Professor of Development Studies at the Universidad Autónoma de Zacatecas in Mexico, and visiting scholar at Cornell University in the USA. He has conducted research into social transformation processes for more than 25 years. His primary research interests are industrial sociol- ogy and the sociology of labour, local and workers’ self-management, and so- cial movements and protest, with a focus on South America and Europe. He has published more than 20 books, 11 films, and a multitude of academic ar- ticles, many of which have been translated into a variety of languages. Among them are Vom Protest zum sozialen Prozess: Betriebsbesetzungen und Arbei ten in Selbstverwaltung (VSA 2018) and The Class Strikes Back: SelfOrganised Workers’ Struggles in the TwentyFirst Century (Haymarket 2019). Further in- formation can be found at www.azzellini.net. Dario Azzellini (ed.) If Not Us, Who? Global workers against authoritarianism, fascism, and dictatorships A publication by the Rosa-Luxemburg-Stiftung VSA: Verlag Hamburg www.vsa-verlag.de www.rosalux.de This publication was financially supported by the Rosa-Luxemburg-Stiftung with funds from the Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development (BMZ) of the Federal Republic of Germany. The publishers are solely respon- sible for the content of this publication; the opinions presented here do not reflect the position of the funders. Translations into English: Adrian Wilding (chapter 2) Translations by Gegensatz Translation Collective: Markus Fiebig (chapter 30), Louise Pain (chapter 1/4/21/28/29, CVs, cover text) Translation copy editing: Marty Hiatt English copy editing: Marty Hiatt Proofreading and editing: Dario Azzellini This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution–Non- Commercial–NoDerivs 3.0 Germany License. -

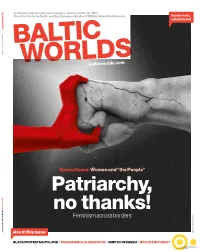

Patriarchy, No Thanks!

BALTIC WORLDSBALTIC A scholarly journal and news magazine. January 2020. Vol. XIII:1. From the Centre for Baltic and East European Studies (CBEES), Södertörn University. Gender hate, a global trend January 2020. Vol. XIII:1 Vol. 2020. January BALTIC WORLDSbalticworlds.com Special Issue: Women and “the People” Patriarchy, Special Issue: Issue: Special Women and “the People” “the and Women no thanks! Feminism across borders also in this issue Sunvisson Karin Illustration: BLACK PROTESTS IN POLAND / #NIUNAMENOS IN ARGENTINA / #METOO IN RUSSIA / MARCH 8 IN TURKEY Sponsored by the Foundation BALTIC for Baltic and East European Studies theme issue WORLDSbalticworlds.com Women and “the People” introduction 3 Conflicts and alliances in a polarized world, Jenny editorial Gunnarsson Payne essays 6 Women as “the People”. Reflections on the Black Protests, Worlds and words beyond Jenny Gunnarsson Payne henever I meet a new reader in particular gender studies. Here, 31 Women, gender, and who is unfamiliar with the we aim to go deeper and under- the authoritarianism of journal Baltic Worlds, I have to stand how the rhetoric and the “traditional values” in explain that the journal covers resistance from women as a group Russia, Yulia Gradskova Wa much bigger area than the title indicates. We is connected in time and space. We 37 Did #MeToo skip Russia? include post-socialist countries in Eastern and want to test how we understand Anna Sedysheva Central Europe, Russia, the former Soviet states the changes in our area for women 67 National and transnational (extending down to the Caucasus), and the and gender, by exploring develop- articulations. -

Narratives of Crisis in the Periphery of São Paulo: Place and Political Articulation During Brazil’S Rightward Turn

Journal of Latin American Studies (2020), 1–27 doi:10.1017/S0022216X20000012 ORIGINAL ARTICLE Narratives of Crisis in the Periphery of São Paulo: Place and Political Articulation during Brazil’s Rightward Turn Matthew Aaron Richmond* Visiting Fellow, Latin American and Caribbean Centre (LACC), London School of Economics and Postdoctoral Researcher, Grupo de Pesquisa Produção do Espaço e Redefinições Regionais (GAsPERR), Universidade Estadual Paulista, São Paulo, Brazil. *Corresponding author. Email: [email protected] Abstract Between 2014 and 2018, a period marked by major political and economic upheaval, Brazilian politics shifted sharply to the Right. Presenting qualitative research conducted over 2016–17, this article examines this process from the perspectives of residents of a peri- pheral São Paulo neighbourhood. Analysis is presented of three broad groups of respon- dents, each of which mobilised a distinct narrative framework for interpreting the crisis. Based on this, I argue that the rightward turn in urban peripheries embodies not a signifi- cant ideological shift, but rather long-term transformations of place and the largely con- tingent ways these articulate with electoral politics. Keywords: Brazil; peripheries; place; political attitudes; crisis; subjectivity; Partido dos Trabalhadores (PT) Introduction On 28 October 2018, after a bitter and highly polarised election campaign, far-right congressman Jair Bolsonaro of the Partido Social Liberal (Social Liberal Party, PSL) defeated his opponent, Fernando Haddad of the leftist Partido dos Trabalhadores (Workers’ Party, PT), to become President of Brazil. Bolsonaro’s run-off victory, winning 55 per cent of valid votes, completed a dramatic rightward turn in Brazilian electoral politics since 2014, when former president Dilma Rousseff had achieved re-election to begin a fourth successive term of PT-led government. -

LATIN AMERICAN POLITICS and SOCIETY 62: 2 of a Conservative Politician Did Not Reflect a Preference for Conservative Policies

BOOK REVIEWS 17 ruption. But in order to be effective, these changes have to occur at the apex of soci- ety. National leaders have to have a strong political will to introduce changes, even at the cost of creating powerful enemies in several sectors. Moreover, the probity and independence of the judicial system are essential requirements for any chance to be effective in the battle against corruption. However, the capture of the state by organized crime in many Latin American countries makes it practically impossible to combat corruption, since key local actors and institutions are themselves part of the problem. An interesting proposal formu- lated by Rotberg is the creation of a Latin American anticorruption court, with a comprehensive mandate to deal with gross cases of abuse of public office in the region. Te UN CICIG initiative in Guatemala has already proved that interna- tional commissions can be quite effective in denouncing cases of corruption involv- ing the highest circles of power. Te idea to establish a Latin American anticorrup- tion court will certainly generate multiple objections. Nevertheless, the fact remains that most Latin American countries have, until now, completely failed to combat big corruption through their own political and judicial institutions. Patricio Silva Leiden University Noam Lupu, Virginia Oliveros, and Luis Schiumerini, eds., Campaigns and Voters in Developing Democracies: Argentina in Comparative Perspective. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2019. Figures, tables, bibliography, index, 304 pp.; hardcover $80, ebook $64.95. Argentina’s 2015 elections saw the right-leaning Mauricio Macri of the Propuesta Republicana (Republican Proposal) Party come back from an early deficit to defeat Peronist Daniel Scioli, the nominee of the incumbent Frente para Victoria (Front for Victory) Party, whose leader, incumbent Christina Fernández de Kirchner, was term-limited. -

The Perfect Misogynist Storm and the Electromagnetic Shape of Feminism: Weathering Brazil’S Political Crisis

Journal of International Women's Studies Volume 20 Issue 8 Issue #2 (of 2) Women’s Movements and the Shape of Feminist Theory and Praxis in Article 6 Latin America October 2019 The Perfect Misogynist Storm and The Electromagnetic Shape of Feminism: Weathering Brazil’s Political Crisis Cara K. Snyder Cristina Scheibe Wolff Follow this and additional works at: https://vc.bridgew.edu/jiws Part of the Women's Studies Commons Recommended Citation Snyder, Cara K. and Wolff, Cristina Scheibe (2019). The Perfect Misogynist Storm and The Electromagnetic Shape of Feminism: Weathering Brazil’s Political Crisis. Journal of International Women's Studies, 20(8), 87-109. Available at: https://vc.bridgew.edu/jiws/vol20/iss8/6 This item is available as part of Virtual Commons, the open-access institutional repository of Bridgewater State University, Bridgewater, Massachusetts. This journal and its contents may be used for research, teaching and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproduction, re-distribution, re-selling, loan or sub-licensing, systematic supply or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. ©2019 Journal of International Women’s Studies. The Perfect Misogynist Storm and The Electromagnetic Shape of Feminism: Weathering Brazil’s Political Crisis By Cara K. Snyder1 and Cristina Scheibe Wolff2 Abstract In Brazil, the 2016 coup against Dilma Rousseff and the Worker’s Party (PT), and the subsequent jailing of former PT President Luis Ignacio da Silva (Lula), laid the groundwork for the 2018 election of ultra-conservative Jair Bolsonaro. In the perfect storm leading up to the coup, the conservative elite drew on deep-seated misogynist discourses to oust Dilma Rousseff, Brazil’s progressive first woman president, and the Worker’s Party she represented. -

Latam Outlook 2021

LatAm Outlook 2021 Where thethe UKUK meets LatinLatin AmericaAmerican and & IberiaIberia ISBN number: 978-1-9165047-4-5 Edited by Ian Perrin, Cristina Cortes, and Joe Brandon This report has been compiled and published by Contents Canning House 126 Wigmore Street, Biographies P. 4 London, W1U 3RZ Overview P. 6 Telephone: +44 (0) 207 811 5600 Political Outlook P. 9 Email: [email protected] Regional Trends P. 9 Country Political Outlooks P. 16 Economic Outlook P. 29 Regional Trends P. 29 Country Economic Outlooks P. 32 Health Outlook P. 45 Social Outlook P. 59 Regional Overview P. 59 Perceptions of 2020 P. 60 What worries Latin America P. 60 What will happen in 2021? P. 63 Environmental Outlook P. 69 Security & Corruption Outlook P. 79 Regional Trends P. 79 Copyright © 2021, Canning House in all countries. Country Security & Corruption Outlooks P. 82 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, Conclusions P. 96 stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, electrical, chem- ical, mechanical, optical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publishers. Page 2 - LatAm Outlook 2021 Page 3 - LatAm Outlook 2021 Biographies Cristina Cortes, CEO, Canning House Dr Clare Wenham, Assistant Professor of Global Health Policy, London School of Economics Cristina Cortes is an Oxford and LSE politics and economics graduate. Having worked in government, Clare Wenham is Assistant Professor of Global Health Policy at London School of Economics banking and energy across a variety of commercial, and Political Science (LSE). She specialises in global health security and the politics and policy business development and government relations roles of pandemic preparedness and outbreak response, through analysis of influenza, Ebola in London, Houston, Venezuela, Colombia, Argentina and Zika. -

Education in Eastern Europe: the New Conservative Wave Tomas Kozma, Hungarian Institute for Educational Research

Education in Eastern Europe: The New Conservative Wave Tomas Kozma, Hungarian Institute for Educational Research The "East-bloc countries" represent about one third of the population and about one half of the continent of Europe. Yet, since World War II until the mid-1980s, they were viewed by the Soviets, as well as by their own leaders, as "the member countries of the socialist camp". The other part of Europe echoed this view. They called Eastern Europe the "satellite countries" or simply "the Communist bloc". The events of the late 1980s surprised both East and West. The peoples of that remote part of the continent made it clear that they would not belong to "Eastern Europe" anymore - and also, that they did not necessarily want to be an appendage of the West. They are deeply committed to "Europe" in the French sense - a concept, used mainly by opposition movements like Romania Libera. Or they try to revive another concept that we thought had been buried forever, namely that of "Central Europe" - a German concept used by movements like the Hungarian Democratic Forum or the Slovenian Social Democrats. Renaming themselves is far more than a game of the intellectuals. it represents a crisis of legitimacy faced by both ruling parties and opposition forces in Eastern Europe today. The Soviet leadership does not support "the old guard" anymore. Those who have not built up any grassroot legacies will ultimately go. Others, like the Bulgarians or the Hungarians, may be experimenting with peaceful transitions, their public policies aimed at forming welfare states. They called themselves socialist states and insisted upon ideological monopoly. -

Corruption, Populism and the Crisis of the Rule of Law in Brazil

CORRUPTION, POPULISM AND THE CRISIS OF THE RULE OF LAW IN BRAZIL CORRUPÇÃO, POPULISMO E A CRISE DO “RULE OF LAW” NO BRASIL Alberto do Amaral Junior * Mariana Boer Martins** RESUMO: O mundo testemunhou recentemente o aumento do ABSTRACT: The world has recently witnessed the rise of populism populismo e do autoritarismo em várias democracias. O Brasil , é and authoritarianism in several democracies. Brazil, of course, is claro, não é exceção. No entanto, o processo que culminou com o no exception. However, the process that culminated in the result of resultado das últimas eleições presidenciais brasileiras é the last Brazilian presidential elections is fundamentally different fundamentalmente diferente do que tem sido observado em alguns from that which has been observed in some countries of the Global países do Norte Global. Embora a raiz da atual situação política no North. Although the root cause of the current political situation in Brasil seja complexa, um de seus principais fatores é o nível Brazil is complex, one of its main factors is the country’s notoriously notoriamente alto de corrupção do país. A hipótese que o presente high level of corruption. The hypothesis which the present article artigo pretende explorar é a de que existe uma articulação entre a aims to explore is that there is a linkage between the disclosure of divulgação das investigações realizadas no âmbito da Operação the investigations which were carried out in the context of Lava Jato, lançada em 2014 pela Polícia Federal do Brasil, e a subida Operation Car Wash, launched in 2014 by the Federal Police of ao poder de um governo populista de direita. -

Emergence of Socialism Oriented International Economic Order

Volume 8 Issue 1 2020 Kathmandu School of Law Review Kathmandu School of Law Review (KSLR), Volume 8, Issue 1, 2020, pp 21-39 https://doi.org/10.46985/kslr.v8i1.2126 © KSLR, 2020 Emergence of Socialism Oriented International Economic Order Iris Lobo* Abstract Winston Churchill had once said that ‘Socialism is a philosophy of failure, the creed of ignorance, and the gospel of envy; its inherent virtue is the equal sharing of misery.’ This was the belief that was once upheld staunchly in all its rigidity amongst the majority of the people in the neoliberal world; who believed in their own gospel of free markets and worshipped the deity of deregulation. However, when Covid-19 struck society with ruthlessness, the common people and even the high priests of global capitalism were willing to scrap decades of neoliberal orthodoxy to alleviate the catastrophic effects of the pandemic and the subsequent economic crisis. A conversion was vehemently demanded and socialism was to be their baptism. This paper analyses the journey of socialism from a Pre-Covid-19 society, a Covid-19 riddled society and then its emergence into an internationally observed economic order in a Post-Covid-19 world. For contrary to what Churchill believed, the Covid-19 catalyst, as captured in this paper, resulted in the revelation of the shroud of neoliberalism and the failure of the philosophy of laissez faire, the awakening of ‘class consciousness’ from its slumber of ignorance, and a gospel of collectivism and communal spirit that the working-class were going to take with, moving forward into a socialism oriented Post-Covid-19 society.